German Peasants' War

Thomas Müntzer became a follower of Martin Luther and in 1519 he spoke out against the Franciscan order, the Roman Catholic ecclesiastical hierarchy, and the veneration of the saints. He did not always agree with Luther and showed himself to be an independent thinker. In 1520 he moved to Beuditz Monastery at Weissenfels. "There he developed, especially under the influence of mysticism, his own view of Christianity, which became increasingly apocalyptic and spiritual. From an action-hungry conspirator in local burgher plots, he became a Reformer who began to see the work inaugurated by Luther as a fundamental change in both ecclesiastical and secular life and therefore as a revolution." (1)

Luther had been born a peasant and he was sympathetic to their plight in Germany and attacked the oppression of the landlords. In December 1521 he warned that the peasants were close to rebellion: "Now it seems probable that there is danger of an insurrection, and that priests, monks, bishops, and the entire spiritual estate may be murdered or driven into exile, unless they seriously and thoroughly reform themselves. For the common man... is neither able nor willing to endure it longer, and would indeed have good reason to lay about him with flails and cudgels, as the peasants are threatening to do." (2)

Henry Ganss accused Luther of creating a revolutionary situation: "Luther the reformer had become Luther the revolutionary; the religious agitation had become a political rebellion... Luther had one prominent trait of character, which in the consensus of those who have made him a special study, overshadowed all others. It was an overweening confidence and unbending will, buttressed by an inflexible dogmatism. He recognized no superior, tolerated no rival, brooked no contradiction." (3)

Thomas Müntzer in Allstedt

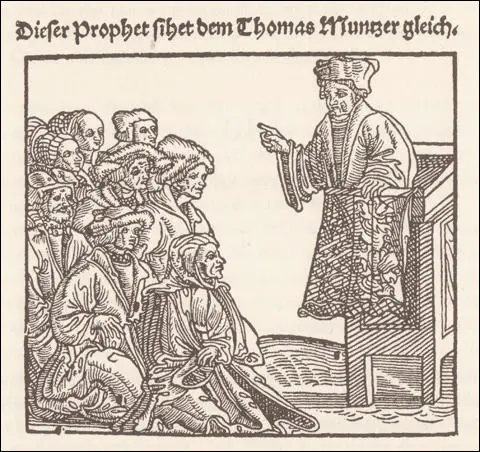

In 1523 Müntzer became a preacher in Allstedt. It was only a small town in the neighborhood of rich ore mines which produced a "restless class of miners always eager to promote social changes". Although the town only had a population of a few hundred it is claimed that his sermons were attended by as many as 2,000 people. (4) Müntzer supported the miners in their attempts to form trade unions. This brought him into conflict with Lutherans. (5)

Martin Luther wrote a letter to George Spalatin, a Lutheran living in the area. He advised all Lutherans to withdraw their support of Müntzer and accused him of "abusing Scripture". Luther was concerned that his inflammatory preaching style had led to violence. (6) Eric W. Gritsch has argued that Müntzer activities "had made Luther nervous; he hated chaos and had already warned against engaging in rebellious activities." (7)

Thomas Müntzer formed the Allstedt League, a society committed to reform. During this period Robert Friedmann has claimed: "Müntzer lost altogether his sense of reality and embarked on a road of romantic fanaticism". (8) Müntzer believed that his teachings came from the Holy Spirit. This placed him in opposition to the Lutheran doctrines of justification (justification by faith alone) and of the authority of Scripture (Scripture as the exclusive source of divine truth). "The revolutionary aspect of Müntzer’s theology lay in the link he made between his concept of the inevitable conquest of the anti-Christian earthly government and the thesis that the common people themselves, as the instruments of God, would have to execute this change. He believed that the common people, because of their lack of property and their unspoiled ignorance, were God’s elect and would disclose his will." (9)

Rebellion in Mühlhausen

On 15th August 1524 Thomas Müntzer arrived in Mühlhausen. He began arguing that his reformist ideas should be applied to the economics and politics as well as religion. Müntzer began promoting a new egalitarian society. Frederick Engels wrote that Müntzer believed in "a society with no class differences, no private property and no state authority independent of, and foreign to, members of society". (10)

Müntzer began calling for rebellion. In one speech he told the peasants: "The worst of all the ills on Earth is that no-one wants to concern themselves with the poor. The rich do as they wish... Our lords and princes encourage theft and robbery. The fish in the water, the birds in the sky, and the vegetation on the land all have to be theirs... They... preach to the poor: 'God has commanded that thou shalt not steal'. Thus, when the poor man takes even the slightest thing he has to hang." (11)

Martin Luther seemed to take the side of the peasants and in May 1525 he published An Admonition to Peace: A Reply to the Twelve Articles of the Peasants in Swabia: "To the Princes and Lords... We have no one on earth to thank for this mischievous rebellion, except you princes and lords; and especially you blind bishops and mad priests and monks... since you are the cause of this wrath of God, it will undoubtedly come upon you, if you do not mend your ways in time. ... The peasants are mustering, and this must result in the ruin, destruction, and desolation of Germany by cruel murder and bloodshed, unless God shall be moved by our repentance to prevent it... If these peasants do not do it for you, others will... It is not the peasants, dear lords, who are resisting you; it is God Himself. ... To make your sin still greater, and ensure your merciless destruction, some of you are beginning to blame this affair on the Gospel and say it is the fruit of my teaching... You did not want to know what I taught, and what the Gospel is; now there is one at the door who will soon teach you, unless you amend your ways." (12)

In March 1525, Thomas Müntzer succeeded in taking over the Mühlhausen town council and setting up a type of communistic society. By the spring of 1525 the rebellion, known as the Peasants’ War, had spread to much of central Germany. The peasants published their grievances in a manifesto titled The Twelve Articles of the Peasants; the document is notable for its declaration that the rightness of the peasants’ demands should be judged by the Word of God, a notion derived directly from Luther’s teaching that the Bible is the sole guide in matters of morality and belief. (13)

Although it is true that Martin Luther he agreed with many of the peasants' demands, he hated armed strife. He travelled round the country districts, risking his life to preach against violence. Martin Luther also published the tract, Against the Murdering Thieving Hordes of Peasants, where he urged the princes to "brandish their swords, to free, save, help, and pity the poor people forced to join the peasants - but the wicked, stab, smite, and slay all you can." Some of the peasant leaders reacted to the tract by describing Luther as a spokesman for the oppressors. (14)

In the tract Luther made it clear that he now had no sympathy for the rebellious peasants: "The pretences which they made in their twelve articles, under the name of the Gospel, were nothing but lies. It is the devil's work that they are at.... They have abundantly merited death in body and soul. In the first place they have sworn to be true and faithful, submissive and obedient, to their rulers, as Christ commands... Because they are breaking this obedience, and are setting themselves against the higher powers, willfully and with violence, they have forfeited body and soul, as faithless, perjured, lying, disobedient knaves and scoundrels are wont to do."

Luther called on the nobility of Germany to destroy the rebels: "They (the peasants) are starting a rebellion, and violently robbing and plundering monasteries and castles which are not theirs, by which they have a second time deserved death in body and soul, if only as highwaymen and murderers ... if a man is an open rebel every man is his judge and executioner, just as when a fire starts, the first to put it out is the best man. For rebellion is not simple murder, but is like a great fire, which attacks and lays waste a whole land. Thus rebellion brings with it a land full of murder and bloodshed, makes widows and orphans, and turns everything upside down, like the greatest disaster." (15)

Derek Wilson, the author of Out of the Storm: The Life and Legacy of Martin Luther (2007), pointed out the Luther strongly defended the inequality that existed in 16th century Germany. "Luther told the peasants... the rebels have no mandate from God to challenge their masters and, as Jesus had shown by his rebuking of Peter who had drawn the sword in the Garden of Gethsemane, violence was never an option for the Christian. Vengeance and the rightings of wrongs belonged to God... Luther went through their twelve demands. The abolition of serfdom was fanciful nonsense; equality under the Gospel does not translate into the removal of social grading. Without class distinctions society would disintegrate into anarchy. By the same token, the withholding of tithes would be an unwarranted attack on the economic working of the prevailing system." (16)

Peasants' War

Thomas Müntzer led about 8,000 peasants into battle in Frankenhausen on 15th May 1525. Müntzer told the peasants: "Forward, forward, while the iron is hot. Let your swords be ever warm with blood!" Armed with mostly scythes and flails they stood little chance against the well-armed soldiers of Philip I of Hesse and Duke George of Saxony. The combined infantry, cavalry and artillery attack resulted in the peasants fleeing in panic. Over 3,000 peasants were killed whereas only four of the soldiers lost their lives. (17)

Müntzer was captured on 25th May. Anticipating his execution, Müntzer dictated a letter on 17th May to friends in Mühlhausen from his prison in Heldrungen. He asked them to take care of his wife and to dispose of his possessions, consisting mostly of books and clothes. (18) Müntzer was tortured and finally executed on 27th May, 1525. His head and body were displayed as a warning to all those who might again preach treasonous doctrines. (19)

Müntzer was captured, tortured and finally executed on 27th May, 1525. His head and body were displayed as a warning to all those who might again preach treasonous doctrines. Other ringleaders were also executed. "Meanwhile, all over Germany, the mopping-up operation got under way as the princes exacted their revenge and reasserted their authority. Men who had taken up arms or simply against their masters or who fell foul of informers were imprisoned or beheaded... To any unbiased commentator, then or twice, the reaction has seemed to be out of all proportion to the offence." (20)

Martin Luther wrote to his friend, Nicolaus von Amsdorf, justifying his position on the Peasants War: "My opinion is that it is better that all the peasants be killed than that the princes and magistrates perish, because the rustics took the sword without divine authority. The only possible consequence of their satanic wickedness would be the diabolic devastation of the kingdom of God. Even if the princes abuse their power, yet they have it of God, and under their rule the kingdom of God at least has a chance to exist. Wherefore no pity, no tolerance should be shown to the peasants, but the fury and wrath of God should be visited upon those men who did not heed warning nor yield when just terms were offered them, but continued with satanic fury to confound everything... To justify, pity, or favor them is to deny, blaspheme, and try to pull God from heaven." (21)

In July 1525, published An Open Letter Against the Peasants, where he attempted to regain the support of those who had supported the rebels: "All my words were against the obdurate, hardened, blinded peasants, who would neither see nor hear, as anyone may see who reads them; and yet you say that I advocate the slaughter of the poor captured peasants without mercy.... On the obstinate, hardened, blinded peasants, let no one have mercy. They say... that the lords are misusing their sword and slaying too cruelly. I answer: What has that to do with my book? Why lay others' guilt on me? If they are misusing their power, they have not learned it from me; and they will have their reward ... See, then, whether I was not right when I said, in my little book, that we ought to slay the rebels without any mercy. I did not teach, however, that mercy ought not to be shown to the captives and those who have surrendered." (22)

Primary Sources

(1) Robert Friedmann, Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online (1987)

Thomas Müntzer was perhaps the most controversial figure of the period of the German Reformation, a man who has been called at various times the "beginner of the great Anabaptist movement," the forerunner of modern socialism, the beginner of the mystical-spiritualistic movement in Germany, a religious socialist, the leader in the Peasants' War 1525, and other such designations, none of which really fit this versatile man who during the decisive last five years of his life (1520-1525) changed his position almost from year to year. Karl Holl's assertion that most of the catchwords or slogans of the German Reformation during its formative period were made current by this fiery and restless mind is acceptable. Noble and deep thoughts mingle in his writings with rather coarse and rude expressions, not to say offensive passages; genuine spirituality alternates with fanciful inspirationism. At the end, in spite of his position as a priest and preacher, one may legitimately ask: Was he still a Christian?

The literature about Müntzer is extensive but not too enlightening, providing for each author an occasion for personal interpretation of an ambiguous personality, thereby using categories often wanting in precision. Praise and blame, love and hatred speak from these writings, but no author seems to be able to be fully neutral and detached. But since Müntzer has quite persistently been called the "originator of the great Anabaptist movement" it is desirable that a careful and objective study be made of his relation to Anabaptism.

(2) Ernest Belfort Bax, The Peasants War in Germany (1987)

Thomas Münzer appears to have been born in the last decade of the fifteenth century. An uncertain tradition states that his father was hanged by the Count of Stolberg. The first we hear of him with certainty is as teacher in the Latin school at Aschersleben and afterwards at Halle. Where he studied is doubtful, but by this time he had already graduated as doctor. In Halle he is alleged to have started an abortive conspiracy against the Archbishop of Magdeburg. In 1515 we find him as confessor in a nunnery and afterwards as teacher in a foundation school at Brunswick. Finally, in 1520, he became preacher at the Marienkirche at Zwickau, and here his public activity in the wider sense really began. The democratic tendencies previously displayed by him broke all bounds. He thundered against those who devoured widows’ houses and made long prayers and who at death-beds were concerned not with the faith of the dying but with the gratification of their measureless greed.

At this time Münzer was still a follower of Luther, but it was not long before he found him a lukewarm church-reformer. Luther’s bibliolatry, as opposed to his own belief in the continuous inspiration of certain chosen men by the Divine spirit, excited his opposition. He criticised still more severely as an unpardonable inconsistency Luther’s retention of certain dogmas of the old Church whilst rejecting others. He now began to study with enthusiasm the works of the old German mystics, Meister Eck and Johannes Tauler, and more than all those of Joachim Floras, the Italian enthusiast of the twelfth century. A general conviction soon came uppermost in his mind of the necessity of a thorough revolution alike of Church and State.

His mystical tendencies were strengthened by contact with a sect which had recently sprung up amongst the clothworkers of Zwickau, and of which one Nicholas Storch, a master clothworker, was corypheus. The sect in question lived in a constant belief in the approach of a millennium to be brought about by the efforts of the “elect”. Visions and ecstasies were the order of the day amongst these good people. This remarkable sect influenced various prominent persons at this time. Karlstadt was completely fascinated by them. Melancthon was carried away; and even Luther admits having had some doubts whether they had not a Divine mission. The worthy Elector Friedrich himself would take no measures against them, in spite of the dangerous nature of their teaching from the point of view of political stability. He was afraid, as he said “lest perchance he should be found fighting against God”.

It was not long before Münzer allied himself with these “enthusiasts,” or “prophets of Zwickau,” as they were called. When the patrician council at Zwickau forbade the cloth-workers to preach, Münzer denounced the ordinance and encouraged them to disobey it. New prohibitions followed, culminating in prosecutions and imprisonments. The result was that, by the end of 1521, the cloth-working town had become too hot to hold the new reformers. Some fled to Wittenberg, and others, including Münzer himself, into Bohemia. Arrived in Prague, Münzer posted up an announcement in Latin and German that he would “like that excellent warrior of Christ, Johann Huns, fill the trumpets with a new song”. He proceeded in his addresses to denounce the clergy, and to prophesy the approaching vengeance of heaven upon their order. He here also preached against the “dead letter,” as he called it, of the Bible, expounding his favourite theory of the necessity of believing in the supplemental inspiration of all elect persons. But the soil of Bohemia proved not a grateful one. It had been exhausted by over a century of religious fanaticism and utopistic dreams of social regeneration.

Student Activities

Martin Luther and Thomas Müntzer (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and the Reformation (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Henry VII: A Wise or Wicked Ruler? (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII: Catherine of Aragon or Anne Boleyn?

Was Henry VIII's son, Henry FitzRoy, murdered?

Hans Holbein and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

The Marriage of Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII and Anne of Cleves (Answer Commentary)

Was Queen Catherine Howard guilty of treason? (Answer Commentary)

Anne Boleyn - Religious Reformer (Answer Commentary)

Did Anne Boleyn have six fingers on her right hand? A Study in Catholic Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

Why were women hostile to Henry VIII's marriage to Anne Boleyn? (Answer Commentary)

Catherine Parr and Women's Rights (Answer Commentary)

Women, Politics and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Cardinal Thomas Wolsey (Answer Commentary)

Historians and Novelists on Thomas Cromwell (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Thomas Müntzer (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Hitler's Anti-Semitism (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and the Reformation (Answer Commentary)

Mary Tudor and Heretics (Answer Commentary)

Joan Bocher - Anabaptist (Answer Commentary)

Anne Askew – Burnt at the Stake (Answer Commentary)

Elizabeth Barton and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Execution of Margaret Cheyney (Answer Commentary)

Robert Aske (Answer Commentary)

Dissolution of the Monasteries (Answer Commentary)

Pilgrimage of Grace (Answer Commentary)

Poverty in Tudor England (Answer Commentary)

Why did Queen Elizabeth not get married? (Answer Commentary)

Francis Walsingham - Codes & Codebreaking (Answer Commentary)

Codes and Codebreaking (Answer Commentary)

Sir Thomas More: Saint or Sinner? (Answer Commentary)

Hans Holbein's Art and Religious Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

1517 May Day Riots: How do historians know what happened? (Answer Commentary)