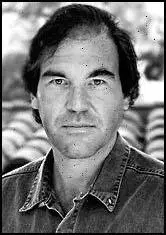

Oliver Stone

Oliver Stone was born in New York City on 15th September, 1946. He attended Yale University but dropped out and taught English at the Free Pacific Institute before working briefly as a merchant marine. Stone returned to university but dropped out for a second time.

Stone now joined the United States Army and served in Vietnam from April 1967 to November 1968 as a member of the 25th Infantry Regiment. He was wounded twice in action and was awarded the Bronze Star for "extraordinary acts of courage under fire."

In 1971 he directed a short film entitled, Last Year in Vietnam. Three years later he wrote and directed a horror film, Seizure. His breakthrough film was Midnight Express (1978) where he won an oscar for the best adapted screenplay.

Stone wrote and directed The Hand (1981). This was followed by Salvador (1986), Platoon (1986), Wall Street (1987), Talk Radio (1988), Born on the Fourth of July (1989) and The Doors (1991). Stone won two Academy Awards for directing Platoon and Born on the Fourth of July.

In 1991 Oliver Stone, decided to make a movie on the assassination of John F. Kennedy. The script for JFK, written by Stone and Zachary Sklar, is based on two different books, On the Trail of the Assassins by Jim Garrison and Crossfire: The Plot that Killed Kennedy by Jim Marrs. Stone took the view that Kennedy was killed because of his attempts to bring an end to the Cold War.

The movie was both a financial and artistic success earning over $205 million worldwide and being nominated for eight Academy Awards. However, the film was attacked by those journalists who had since 1963 had steadfastly defended the lone-gunman theory. Tom Wicker attacked Stone’s portrayal of Jim Garrison as a hero-figure and complained that he had ignored the claims that he was a corrupt political figure. He added that the film treats “matters that are highly speculative as fact and truth, in effect rewriting history”.

Bernard Weinraub argued in the New York Times that the studio should withdraw the movie: "At what point does a studio exercise its leverage and blunt the highly charged message of a film maker like Oliver Stone?" When veteran film critic, Pat Dowell, provided a good review for The Washingtonian, the editor, John Limpert, rejected it on the grounds that he did not want the magazine to be associated with this "preposterous" viewpoint. As a result Dowell resigned as the magazine’s film critic.

Jack Valenti, who at that time was president and chief executive of the Motion Picture Association of America, but in the months following the assassination, was President Lyndon Johnson’s special advisor, denounced Stone's film in a seven-page statement. He wrote, "In much the same way, young German boys and girls in 1941 were mesmerized by Leni Reifenstahl's Triumph of the Will, in which Adolf Hitler was depicted as a newborn God. Both JFK and Triumph of the Will are equally a propaganda masterpiece and equally a hoax. Mr. Stone and Leni Reifenstahl have another genetic linkage: neither of them carried a disclaimer on their film that its contents were mostly pure fiction".

Oliver Stone appeared on the Larry King Show on 20th December 1991. King asked Stone: “Why do you think the Wickers, the Rathers, the Gerald Fords in an op-ed piece in a newspaper – in the Washington Post – why do you think they’re so mad?” Stone replied: “Well, they’re the official priesthood. They have a stake in their version of reality. Here I am – a film-maker, an artist – coming into their territory and I think that they resent that…. I think they blew it (the coverage of the Kennedy assassination) from day one.”

Oliver Stone hit back at his critics in a speech made at the National Press Club on 15th January, 1992. “When in the last twenty years, have we seen serious research from Tom Wicker, Dan Rather, Anthony Lewis?” Stone said they objected to “this settled version of history… lest one call down the venom of leading journalists from around the country.” He pointed out that the criticism of the film mainly came from “older journalists on the right and left” who had in 1963 supported the lone-gunman theory and claimed that their “objectivity is in question here.”

Dan Rather, another long-time lone-gunman advocate, hosted a CBS program on the JFK movie. Rather pointed out that he had reported the Kennedy assassination at the time. He went on to argue: “Long after Oliver Stone has gone onto his next movie and long after a lot of people who have been writing about this now have stopped, I’m going to keep coming on this one.” Rather suggested that a journalist was much more reliable than a film director for interpreting the past: “We do know a lot and there is much to support the Warren Commission’s conclusions, but unanswered questions also abound. Not all of the conspiracy theories are ridiculous… They explain the inexplicable, neatly tie up the loose ends, but a reporter should not, cannot find refuge there. Facts, hard evidence are the journalist’s guide.”

In the interview that Dan Rather carried out for the CBS documentary, he asked Stone: “I don’t understand why you include the press as either conspirators or accomplices to the conspiracy”. Stone replied: “Dan, when the House Report came out implying that there was a probable conspiracy in the murder of both Kennedy and King, why weren’t you running around trying to dig into the case again? I didn’t see you, you know, rush out there and look at some of these three dozen discrepancies that we present in our movie.” Stone added that “whether you accept my conclusion is not the point, we want people to examine this… subject”.

In the first few months after JFK was released, over 50 million people watched the movie. Robert Groden, who had worked as an advisor on the film, predicted that: “The movie will raise public consciousness. People who can’t take the time to read books will be able to see the movie, and in three hours they’ll be able to see what the issues are.”

Tom Wicker was well aware of the danger this film posed: “This movie… claims truth for itself. And among the many Americans likely to see it, particularly those who never accepted the Warren Commission’s theory of a single assassin, even more particularly those too young to remember November 22, 1963, JFK is all too likely to be taken as the final, unquestioned explanation.” This was confirmed by a NBC poll that indicated that 51% of the American public believed, as the movie had suggested, that the CIA was responsible for Kennedy’s death and that only 6% believed the Warren Commission’s lone gunman theory.

Oliver Stone called for the remaining CIA and FBI documents pertaining to the assassination of Kennedy to be released. Clifford Krauss, reported in the New York Times that members of the Kennedy family supported this move. The historian, Stephen Ambrose, argued that “the crime of the century is too important to be allowed to remain unsolved and too complex to be left in the hands of Hollywood movie makers.” Louis Stokes, who had chaired the House Select Committee on Assassinations, also called for the files to be unclassified.

The President John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection Act of 1992, or the JFK Records Act, was passed by the United States Congress, and became effective on 26th October, 1992. The Act requires that each assassination record be publicly disclosed in full, and be available in the collection no later than the date that is 25 years after the date of enactment of the Act (October 26, 2017), unless the President of the United States certifies that: (1) continued postponement is made necessary by an identifiable harm to the military defense, intelligence operations, law enforcement, or conduct of foreign relations; and (2) the identifiable harm is of such gravity that it outweighs the public interest in disclosure. There are currently over 50,000 pages of government documents relating to the assassination that have not been released.

Stone upset leading figures in the Republican Party with his film Nixon (1995). This film provided a critical portrait of Richard Nixon during the Watergate Scandal. Stone has also made two sympathetic documentaries about Fidel Castro: Comandante (2003) and Looking for Fidel (2004).

Other films by Stone include Heaven and Earth (1993), Natural Born Killers (1994), U-Turn (1997), Any Given Sunday (1999), Alexander (2004), World Trade Center (2006), W. (2008), South of the Border (2009) and Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps (2010).

Since 2008 Oliver Stone has been working with Peter J. Kuznick on a ten-part television series, The Untold History of the United States. The first episode appeared on Showtime in November 2012.

Primary Sources

(1) Robert Robbins and Jerrold M. Post, Political Paranoia as Cinematic Motif (1997)

The death of Marilyn Monroe and the assassination of John F. Kennedy have engendered films, television programs, books, and articles. The Kennedy assassination has even produced study groups and an annual convention in Dallas. One of the most remarkable examples of conspiracy portrayed as entertainment, is the film JFK, directed by Oliver Stone (Warner Brothers, 1992). Our purpose is not to review the controversy concerning the circumstances surrounding President Kennedy's assassination (although we do reject the idea that the assassination was part of a conspiracy). Nor is our purpose to review the film (although we will evaluate the film within an aesthetic and literary tradition). Rather we intend to show how the paranoid theme added narrative power and commercial value to the film, to illuminate the part that the paranoid message plays in popular entertainment.

Films are not simply entertainment, they are also cultural, intellectual, and political influences. Research demonstrates the influence on beliefs, attitudes, emotions, and behavior of such films as the anti-nuclear The Day After, the anti-Soviet Amerika, Holocaust, and the multigenerational saga of a black family, Roots. The effect, however, is not so much to change people's minds as to solidify and exaggerate beliefs and attitudes already held. Films do not create cultural trends, but they do accelerate and exaggerate them. A survey and analysis of viewer reaction to JFK demonstrated that this film and others like it can produce "markedly altered emotional states, belief changes spread across specific political issues, and ... an impact on politically relevant behavioral changes. [JFK viewers] reported emotional changes, [became] significantly more angry and less hopeful...Those who had seen the movie were significantly more likely to believe [the various conspiracies depicted in the film]."

JFK is not a historical film in the way that William Makepeace Thackeray's Henry Esmond, Alexandre Dumas's Three Musketeers, and Margaret Mitchell's Gone with the Wind are historical novels. Stone does not take fictional characters and put them in an historical context, as the fictional Scarlett O'Hara and Rhett Butler are placed in civil-war Georgia. Stone takes genuine historical characters - New Orleans District Attorney James Garrison and civic activist Clay Shaw, for example--and presents his version of what happened. Films of this sort are called docudramas because they dramatize historical events and historical characters and for the screen. A film like Gone with the Wind attempts to tell the viewer what things were like, what sorts of things happened in a past historical period. In contrast, a docudrama like JFK attempts to convey a particular version of history; the film does not simply lay out the director's version of history; it seeks to persuade the viewer that the version is the truth.

Film as media presents opportunities and limitations that are absent in a written work. These strengths and restrictions were first demonstrated in D. W. Griffith's seminal American film, The Birth of a Nation (Epic, 1915). This film, which set the "grammar and syntax" of cinema as narrative entertainment, carried a powerful racist message. It idealized the Old South, praised slavery, described Klansmen as heroic saviors of the white South from bestial blacks and their Northern white allies, and opposed racial "pollution." Financially it was very successful. Politically it facilitated the revival of the Ku Klux Klan. Its racism was so simplistic and offensive that, even in an era tolerant of racism, it was banned in several cities and became the object of small riots. Griffith saw himself as the victim of the forces (blacks and their Northern sympathizers) that he "exposed" in the film.

From The Birth of a Nation's release in 1915 to the appearance of JFK in 1992 American historical films developed a cinematic pattern with the following characteristics:

* The story is presented in a filmic style of a seamless visual and aural pattern; the viewer seems to be looking directly at reality;

* The story has a strong moral message;

* The story is simple and definitive. Alternate versions are rarely suggested; if suggested, they are dismissed or mocked;

* The story is about individuals, usually heroic ones, fighting for good in the interest of humanity (that is, the audience);

* The story has a strong emotional tone.

JFK adds several other techniques. It seamlessly interweaves newsreel footage from the assassination with fictional material, so that the boundary between historical fact and the director's or writer's fictional elaborations are progressively blurred. It is crammed with information, presented in words and suggested in pictures. It contains not only many short speeches and several long orations but much dialogue. More important, it includes many scenes without dialog, some seemingly only one or two seconds long, which impart or suggest information. Not one locus of conspiracy is suggested but eight: the CIA, weapons manufacturers, the Dallas police, the armed forces, the White House, the establishment press, renegade anti-Castro Cubans, and the Mafia. The persuasive value of such an onslaught is to leave the viewer, if not convinced, at least believing that "there has to be something to it." One viewer said that she and her companion "walked out of the movie feeling like we had just undergone a powerful 'paranoia induction.'"

These facts, inventions, and insinuations do not necessarily come from the director's private beliefs. They are driven by the commercial and narrative needs of the form. Popular art requires continuity and order, elements generally lacking in genuine events. The film depiction of events must grab the viewer's attention, keep him fixed in his seat, make him identify with the action and principal characters, and induce him to tell his neighbors to buy a ticket for the next performance. The paranoid perspective advances these commercial and artistic ambitions:

* It too gives a simplified view of reality. Indeed, the paranoid world-view is one that demands coherence, even when such consistency is lacking.

* It too takes a moral stand: us against them, good against evil, openness against conspiracy.

* It too presents the "truth" as simple in essence but highly complex in details.

* It too describes a struggle, not between abstract forces, but between individuals and groups.

* It too brings powerful emotions to the narration. Thus, the paranoid message is uniquely suited to the form of a historical film drama, or docudrama. This message is seen most powerfully in JFK but also in other paranoid films: Silkwood, Missing, and The Parallax View.

The paranoid theme complements another influence: deconstruction, a prominent feature of late twentieth century criticism and art. The most important part of the deconstructive position for our purposes is its contention that "texts" (novels, films, poems) have no meaning apart from how they are perceived. If the audience receives the "true" story, then the "facts" in the text are true. Truth is itself a shifting concept whereby the political interests of the creator and the audience (generally expressed in terms of race, gender, and economic position) define what is true. If what is presented persuades people that it is true and if this truth is "politically progressive," then the events presented in the text are true.

(2) David Reitzes, Oliver Stone's Portrayal of Jim Garrison (2001)

When Oliver Stone made Jim Garrison the protagonist of his movie, JFK, the filmmaker scarcely could have imagined what the public's reaction would be. He did not have to wait long to find out, however. Even as filming was just beginning, the reactions began pouring in loud and clear.

"For those who have forgotten or are too young to remember," Dallas Morning News reporter Jon Margolis wrote in May 1991, "Garrison was the bizarre New Orleans district attorney who, in 1969, claimed that the assassination of President John F. Kennedy was a conspiracy by some officials of the Central Intelligence Agency." "Garrison even managed to put one hapless fellow on trial for his role in this alleged conspiracy," Margolis continued. "Having no case, Garrison lost in court."

Washington Post reporter George Lardner, Jr., who had covered Garrison's JFK probe in the late 1960s, received an early draft of the JFK screenplay and promptly weighed in with his opinion. ". . . Oliver Stone is chasing fiction," he wrote. "Garrison's investigation was a fraud."

In Time, Richard Zoglin called Garrison "a wide-eyed conspiracy buff," "somewhere near the far-out fringe of conspiracy theorists, but Stone seems to have bought his version (of the assassination) virtually wholesale."

Even movie critic Joe Bob Briggs got in on the act. "The main role in the movie JFK is not JFK," Briggs writes. "It's not LBJ. It's not Governor Connally or Jackie or Chief Justice Warren or Lee Harvey Oswald or Jack Ruby. The main role in the movie is this flake from Nawluns."

"Of course, if you asked Oliver," Briggs continues, "the only reason we think Jimbo Garrison is a flake is that he's been persecuted by the media conspiracy, the Cuban conspiracy, the FBI conspiracy, the CIA conspiracy, the conspiracy of the doctors at Parkland Hospital, the conspiracy of all the employees at the Texas School Book Depository, and now the conspiracy of all guilty Texans to whitewash what their state did to the President."

(3) Edward Jay Epstein, JFK: Oliver Stone's Fictional Reality (1993)

Well before the advent of the Hollywood pseudo documentary, Karl Marx suggested that all great events and personalities in world history happen twice: "the first time as tragedy, the second as farce." Oliver Stone's film "JFK" represents the second coming of Jim Garrison.

In 1969, when Jim Garrison's Conspiracy-To-Kill-Kennedy trial collapsed, his entire case that the accused, Clay Shaw, had participated in an assassination plot turned out to be based on nothing more than the hypnotized- induced story of a single witness. This witness, Perry Raymond Russo, had testified that he had had no conscious memory of his own conspiracy story before he had been drugged, hypnotized, and fed hypothetical circumstances about the plot he was supposed to have witnessed by the district attorney. To the dismay of his supporters-- and three of his Garrison's staff resigned-- this was the essence of Garrison's show trial: a witness who acknowledged he could not, after this bizarre treatment, separate fantasy from reality. After that, Garrison's meretricious prosecution of it was considered by the press to be, as the New York Times noted in an editorial, "one of the most disgraceful chapters in the history of American jurisprudence." In this debacle, Garrison himself was exposed as a man who had recklessly disregarded the truth when it suited his purposes.

Then, in 1991, a generation later, Garrison re-emerges phoenix-like from the debris as the truth-seeking prosecutor (played by Kevin Costner) in the film "JFK"-- and who brilliantly solves the mystery of the Kennedy Assassination. In this version, there is no hypnosis: the reborn Garrison resourcefully uncovers cogent evidence that Clay Shaw planned the Dallas ambush of President Kennedy in New Orleans with two confederates: David William Ferrie (played by Joe Persci), a homosexual soldier of fortune and Lee Harvey Oswald (played by Gary Oldman). He establishes that this trio, who also participate together in orgies, all worked for the CIA, and were recruited into a conspiracy to seize power in Washington.

Filmed in a grainy semi-documentary style, with newsreels as well as amateur footage incorporated into it, "JFK" purports to reveal the actual truth about the Kennedy Assassination. From the moment it was released, its director Oliver Stone has so passionately defended its factual accuracy that he became, for all practical purposes, the new Garrison. What could be more appropriate in the age of media than a crusading film-maker replacing a crusading District Attorney as the symbol of the truth-finder in society? In this capacity, Oliver Stone-Garrison played out his case on television news programs, talk shows, magazines and the op- ed pages of news papers. He held his own press conferences, with his attractive researcher at his side, met with Congressional leaders, and he, as the original Garrison had done a quarter of a century before, used this public platform to focus attention on the possibility that the government was hiding the truth about the Kennedy Assassination. In exploiting this torment of secrecy, Stone proved far more successful than his predecessor in rousing interest in releasing the classified files pertaining to the assassination.

But where Jim Garrison failed in building a plausible conspiracy case against Clay Shaw, how did Oliver Stone succeed? The answer is that whereas the original Garrison only attempted to coax, intimidate and hypnotize unable witnesses into providing him with incriminating evidence, the new Garrison, Oliver Stone, fabricated for his film the crucial evidence and witnesses that were missing in real life-- even when this license required deliberately falsifying reality and depicting events that never happened. Consider, for example, the way he fabricated Ferrie's dramatic confession to Garrison in a hotel room only hours before he died.

In reality, as well as in Jim Garrison's account of the case, David Ferrie steadfastly maintaining his innocence, insisting he did not know Lee Harvey Oswald, he was not in the CIA, and that he had no knowledge of any plot to kill Kennedy. The last known person to speak to Ferrie was George Lardner, Jr. of the Washington Post, who Ferrie had met with from midnight to 4 a.m. of February 22, 1967. During this interview, Ferrie described Garrison (who he hasn't seen for weeks) as "a joke". Several hours later, Ferrie died of a cerebral hemorrhage.

In "JFK", Oliver Stone invents, and falsifies, his own version of Ferrie's last night. Instead of being calmly interviewed by a reporter in his home, "JFK" shows a panicked Ferrie being doggedly interrogated by Jim Garrison in a hotel suite until he finally break down and confesses. Ferrie names his CIA controller an, in rapid-fire succession, Ferrie admits in the film everything he denied in real life. He acknowledges that he taught Oswald " everything". He then explains that no only does he know Clay Shaw but he is being blackmailed by him and controlled by him. He also admits that he works for the CIA-- along with Oswald, Shaw and "the Cubans", who were the "shooters" in Dallas. He displays intimate knowledge of the plot by explaining that the "shooters" were recruited without told whose orders they were carrying out. He tells a cool Garrison that the plot is "too big" to be investigated, implying that powerful figures are behind it, and that, because they know Ferrie is now talking, they have issued a "death warrant" for him.

After Ferrie leaves Garrison and returns to his apartment, he is shown being chased, held down, and murdered by a bald-headed man who forces pills down his throat. The murderer, who is shown in other fictional scenes as an associate of Shaw, Oswald, and the Anti-Castro Cuban shooters. When Garrison arrives at the murder scene and finds the empty bottle of pills, he concludes Ferrie was murdered which gives Ferrie's earlier revelations to Garrison the force of a death-bed confession. (In reality, the coroner ruled that Ferrie had died from "natural causes"--a verdict that Garrison, as the empowered authority, did not contest).

Oliver Stone's transformations in this scene involves more than some trivial cinematic contrivances. They provide the linkage for the conspiracy. Ferrie's confession connects the team of anonymous Cuban "shooters" in Dallas with Clay Shaw, David Ferrie and Lee Harvey Oswald in New Orleans and, at a higher level, the CIA "untouchables". Whereas in actuality Ferrie denied he was in the CIA, ever knew Oswald, or knew anything about a plot to kill JFK, in the film, Stone has Ferrie confess he was in the CIA, knew and trained Oswald and knew key details of the plot to shoot JFK. These fabricated admissions changes the entire story - just as it would change the story about the execution of Julius and Ethyl Rosenberg if film fabricated a fictional scene showing the Rosen bergs confessing to J. Edgar Hoover that they were part a Communist conspiracy to steal atomic secrets.

And Ferrie's false confessions is not an isolated bit of license. Throughout JFK, in dozens of scenes, Oliver Stone substitutes fiction for fact when it advances his case. He even blatantly contradicts the two books he represents as being the basis for "JFK" - Jim Garrison, " On The Trail of the Assassins" (Warners Books, 1988) and James Marrs, Cross Fire: The Plot That Killed Kennedy (Carroll and Graf, 1990). He makes especially effective use of this substitution technique when it comes to witnesses. Here, like all fictionalizers, he has an advantage over fact finders: he can artfully fashion his replacement witnesses to meet the audience's criteria for what is credible. His substitution of the fictive "Willie O'Keefe" to replace Garrison's flawed witness, Perry Raymond Russo, is a case in point.

(4) Sam Smith, Why they Hate Oliver Stone, Progressive Review (February 1992)

In a hysterical stampede unusual even for the media herd, scores of journalists have taken time off from their regular occupations -- such as boosting the Democrats' most conservative presidential candidate, extolling free trade or judging other countries by their progress towards American-style oligopoly -- to launch an offensive against what is clearly perceived to be the major internal threat to the Republic: a movie-maker named Oliver Stone.

Stone, whose alleged crime was the production of a film called JFK, has been compared to Hitler and Goebbels and to David Duke and Louis Farrakhan. The movie's thesis has been declared akin to alleged conspiracies by the Freemasons, the Bavarian Illuminati, the League of Just Men and the Elders of Zion.

The film has been described as a "three hour lie from an intellectual sociopath." Newsweek ran a cover story headlined: "Why Oliver Stone's New Movie Can't Be Trusted." Another critic accused Stone of "contemptible citizenship," which is about as close to an accusation of treason as the libel laws will permit. Meanwhile, Leslie Gelb, with best New York Times pomposity, settled for declaring that the "torments" of Presidents Kennedy and Johnson over Vietnam "are not to be trifled with by Oliver Stone or anyone."

The attack began months before the movie even appeared, with the leaking of a first draft of the film. By last June, the film had been excoriated by the Chicago Tribune, Washington Post, and Time magazine. These critics, at least, had at least seen something; following the release of the film, NPR's Cokie Roberts took the remarkable journalistic stance of refusing to screen it at all because it was so awful.

Well, maybe not so remarkable, because the overwhelming sense one gets from the critical diatribes is one of denial, of defense of non-knowledge, of fierce clinging to a story that even some of the Stone's most vehement antagonists have to confess, deep in their articles, may not be correct.

Stephen Rosenfeld of the Washington Post, for example, states seven paragraphs into his commentary: "That the assassination probably encompassed more than a lone gunman now seems beyond cavil."

If there was more than one gunman, it follows that there was a conspiracy of some sort and it follows that the Warren Commission was incorrect. It should follow also that journalists writing about the Kennedy assassination should be more interested in what actually did happen than in dismissing every Warren Commission critic as a paranoid. Yet, from the start, the media has been a consistent promoter of the thesis that Rosenfeld now says is wrong beyond cavil.

In fact, not one of the journalistic attacks on the film that I have seen makes any effort to explain convincingly what did happen in Dallas that day. They either explicitly or implicitly defend the Warren Commission or dismiss its inaccuracy as a mere historic curiosity.

Of course, it is anything but. Americans, if not the Washington Post, want to know what happened. And after nearly thirty years of journalistic nonfeasance concerning one of the major stories of our era, a filmmaker has come forth with an alternative thesis and the country's establishment has gone berserk.

Right or wrong, you've got to hand it to the guy. Since the 1960s, those trying to stem the evil that has increasingly seeped into our political system have been not suppressed so much as ignored. Gary Sick's important new book on events surrounding the October Surprise, for example, has not been reviewed by many major publications. The dozens of books on the subject of the Kennedy assassination, in toto, have received nowhere near the attention of Stone's effort. For the first time in two decades, someone has finally caught the establishment's attention, with a movie that grossed $40 million in the first three or four weeks and will probably be seen by 50 million Americans by the time the videotape sales subside.

Further, by early January, Jim Garrison's own account of the case was at the top of the paperback bestseller list and Mark Lane's Plausible Denial had made it to number seven on the hard cover tally. Many of Stone's critics have accused him of an act of malicious propaganda. In fact, it is part of the sordid reality of our times that Hollywood is about the only institution left in our country big and powerful enough to challenge the influence of state propaganda that controls our lives with hardly a murmur from the same journalists so incensed by Stone. Where were these seekers of truth, for example, during the Gulf Massacre? Even if Stone's depiction were totally false, it would pale in comparison with the brutal consequences of the government's easy manipulation of the media during the Iraqi affair.

And, if movies are to be held to the standards set for JFK, where are the parallel critiques of Gone With the Wind and a horde of other cinemagraphic myths that are part of the American consciousness?

No, Stone's crime was not that his movie presents a myth, but that he had the audacity and power to challenge the myths of his critics. It is, in the critics' view, the job of the news media to determine the country's paradigm, to define our perceptions, to give broad interpretations to major events, to create the myths which guide our thought and action. It is, for example, Tom Brokaw and Cokie Roberts who are ordained to test Democratic candidates on their catechism, not mere members of the public or even the candidates themselves. It is for the media to determine which practitioners of violence, such as Henry Kissinger and Richard Helms, are to be statesmen and which, like Lee Harvey Oswald and James Earl Ray, are mere assassins. It is their privilege to determine which of our politicians have vision and which are fools, and which illegal or corrupt actions have been taken in the national interest and which to subvert that interest. And this right, as Leslie Gelb might put it, is not to be trifled with by Oliver Stone or anyone else.

Because he dared to step on the mythic turf of the news media, Stone has accomplished something truly remarkable that goes far beyond the specific facts of the Kennedy killing. For whatever errors in his recounting of that tale, his underlying story tells a grim truth. Stone has not only presented a detailed, if debatable, thesis for what happened in Dallas on one day, but a parable of the subsequent thirty years of America's democratic disintegration. For in these decades one finds repeated and indisputable evidence - Watergate, Iran-Contra, BCCI, the war on drugs, to name just a few - of major politicians and intelligence services working in unholy alliance with criminals and foreign partisans to malevolently affect national policy. And as late as the 1980s, we have documentation from the Continuity in Government program that at least some in the Reagan administration were preparing for a coup d'état under the most ill-defined conditions.

It is one of contemporary journalism's most disastrous conceits that truth can not exist in the absence of revealed evidence. By accepting the tyranny of the known, the media inevitably relies on the official version of the truth, seldom asking the government to prove its case, while demanding of critics of that official version the most exacting tests of evidence. Some of this, as in the case, say, of George Will, is simply ideological disingenuousness. Other is the unconscious influence of one's caste, well exemplified by Stone critic Chuck Freund, a onetime alternative journalist whose perceptions changed almost immediately upon landing a job with the Washington Post, and who now writes as though he was up for membership in the Metropolitan Club. But for many journalists it is simply a matter of a childish faith in known facts as the delimiter of our understanding.

If intelligence means anything, it means not only the collection of facts, but arranging them into some sort of pattern of probability so we can understand more than we actually know.

Thus the elementary school child is inundated with facts because that is considered all that can be handled at that point. Facts at this level are neatly arranged and function as rules to describe a comfortable, reliable world.

Beginning in high school, however, one starts to take these facts and interpret them and put them together in new orders and to consider what lots of facts, some of them contradictory, might mean. In school this is not called paranoia, nor conspiracy theory, but thought.

Along the way, it is discovered that some of the facts, a.k.a. rules, that we learned in elementary school weren't facts. I learned, for example, that despite what Mrs. Dunn said in 5th grade, Arkansas was not pronounced R-Kansas.

Finally, those who go to college learn that facts aren't anywhere as much help as we even thought in high school, for example when we attempt a major paper on what caused the Civil War.

To deny writers, ordinary citizens or even filmmakers the right to think beyond the perimeter of the known and verifiable is to send us back intellectually into a 5th grade world, precise but inaccurate, and - when applied to a democracy - highly dangerous. We have to vote, after all, without all the facts.

As Benjamin Franklin noted, one need not understand the law of gravity to know that if a plate falls on the floor it will break. Similarly, none of us have to know the full story of the JFK assassination to understand that the official story simply isn't true.

Oliver Stone has done nothing worse than to take the available knowledge and assemble it in a way that seems logical to him. Inevitably, because so many facts are unknown, the movie must be to some degree myth.

Thus, we are presented with two myths: Stone's and the official version so assiduously guarded by the media. One says Kennedy was the victim of forces that constituted a shadow government; the other says it was just a random event by an lone individual.

We need not accept either, but of the two, the Stone version clearly has the edge. The lone gunman theory, (the brainstorm of Arlen Specter, whose ethical standards were well displayed during the Thomas hearings) is so weak that even some of Stone's worst critics won't defend it in the face of facts such as the nature of the weapon allegedly used (so unreliable the Italians called it the humanitarian rifle), the exotic supposed path of the bullet, and Oswald's inexplicably easy return to the US after defecting to the Soviet Union.

In the end, David Ferrie in the movie probably said it right: "The f***king shooters don't even know" who killed JFK. In a well-planned operation it's like that.

I tend to believe that Stone is right about the involvement of the right-wing Cubans and the mobs, that intelligence officials participated at some level, that Jim Garrison was on to something but that his case failed primarily because several of his witnesses mysteriously ended up dead, and that a substantial cover-up took place. I suspect, however, that the primary motive for the killing was revenge - either for a perceived détente with Castro or for JFK's anti-Mafia moves, and that Stone's Vietnam thesis is overblown. The top level conspiracy depicted is possible but, at this point, only that because the case rests on too little - some strange troop movements, a telephone network failure and the account of Mr. X - who turns out albeit to be Fletcher Prouty, chief of special operations for the Joint Chiefs at the time.

But we should not begrudge Stone if he is wrong on any of these points, because he has shown us something even more important than the Kennedy assassination: an insight into repeated organized efforts by the few to manipulate for their own benefit a democracy made too trusting of its invulnerability by a media that refuses to see and tell what has been going on.

Just as the Soviets needed to confront the lies of their own history in order to build a new society, so America must confront the lies of the past thirty years to move ahead, Stone - to the fear of those who have participated in those lies and to the opportunity of all those who suffered because of them - has helped to make this possible.

(5) William D. Romanowski, Journal of Popular Film and Television (Summer, 1993)

Film has long been recognized as a powerful transmitter of culture because it transmits beliefs, values, and knowledge; serves as cultural memory; and offers social criticism. Consequently, the cinema remains a continual battleground in the cultural conflicts in America. The reform efforts of the Progressives in the early twentieth century and the HUAC investigations of Hollywood personnel in the late 1940s and '50s demonstrate one example of the enduring public concern over the "quasi-educational" role of film in American life.

Perhaps no film in recent history has captured more attention and generated more controversial debate about the persuasive power of a motion picture than writer/director Oliver Stone's JFK. Even before this three-hour $40 million Warner Brothers production reached theaters on 20 December 1991, veteran journalists, determined to protect their own coverage of the events in 1963, attacked the picture as a polemic distortion of history, a propagandistic blend of fact and fiction, evidence and speculation. While the film was running in theaters, former Warren Commission staff defended the conclusions of their investigation in the 1960s; the Navy pathologists confirmed the findings of their autopsy on Kennedy as well. In the end, JFK became the catalyst for direct political action. On 27 October 1992, former President Bush signed into law a resolution establishing an independent, five-member board appointed by the president to review and release files accumulated by the Warren Commission and two later congressional investigations, as well as FBI and CIA materials.

The most publicized debates over JFK were directed at the film's claim to historical truth and the legitimacy of the commercial filmmaker, and especially toward Oliver Stone, as a reteller of the past. There were other films made prior to JFK, both commercial and documentary, that challenged the Warren Commission's findings, but none created the controversy that surrounded Oliver Stone's production. This is in part because JFK entered the cultural dialogue in the early 1990s, a time of tremendous conflict over the meaning and destiny of America; interpretations of the past were charged with greater significance in the struggle over national identity than ever before.

By examining how Stone constructed his narrative about the assassination, we can observe the complexity of turning historical subject matter into a commercially successful film in the classic Hollywood narrative style, while also uncovering Stone's version of the assassination. Moreover, the box office success of the movie and the concurrent debate indicated more than mere fascination with the Kennedy assassination. The whole affair demonstrated how effective a motion picture can be as a transmitter of knowledge, history, and culture. As a result, the debate about the validity of JFK extended much further into the war-torn cultural landscape of America in the 1990s than most observers have noted. The JFK controversy was a telling incident demonstrating the larger cultural conflict over values and meaning in America and the competition to define national identity. Though largely neglected by most critics, the response of religious conservatives to JFK, in particular, showed how the cultural war over the future of America was in part waged through interpretations of the past, even those of a commercial filmmaker.

No other medium can approximate the realism of film, regarding its ability to allow the viewer to experience, i.e., "hear" and "see" the course of events taking shape in a certain way. By putting even seemingly unrelated actions together into a coherent narrative form, a film can juxtapose people, events, and circumstances in such a way as to offer an interpretation of their meaning and significance. As film historian David A. Cook explained, in distinction from a literary narrative, "film constructs its fictions through the deliberate manipulation of photographed reality itself, so that in cinema artifice and reality become quite literally indistinguishable" (93-4). The realism of the cinema, then, charges the artist's interpretation with authenticity, especially for an uninformed audience.

In this manner, JFK became a seamless montage of possibilities, blending historical evidence and speculation. The film overwhelmed the viewer with information presented in the quick-editing style of MTV music videos. "It is like splinters to the brain," Stone said of the MTV-styled imagery in JFK. "We were assaulting the senses in a kind of new-wave technique". Stone exploited the images and icons captured by the extraordinary television coverage of the events surrounding the assassination and seared into the collective memory. The combination of re-shot documentary footage with the original, simulations, and reenactments staged and shot on the actual location contributed to the film's claim of authenticity while also playing with audience expectations. The result was a heightening of the film's realism, a fantastic cinematography that, as critics maintained, was also a propagandistic technique: selective storytelling blending fact and fiction. By employing historical images in a different context of meaning, i.e., a narrative giving an alternative interpretation of the events surrounding the assassination, Stone intensified his demythologizing of the Warren Commission's lone gunman theory.

Los Angeles Times film critic Jack Mathews made the statement, "Filmmakers have a tacit responsibility not to lie or distort truth when truth is the very thing they claim to present". Regarding the Kennedy assassination, however, Stone's co-scriptor Zachary Sklar argued, "Since nobody agrees on anything, nobody is distorting history. The only official history is the Warren Commission report, and that nobody believes". Consistently since 1966, public opinion polls have shown that a majority of Americans believe there was a conspiracy involved in the assassination. More recently, U.S. News and World Report said that only 10 percent of Americans believed the Warren Commission's conclusion that Oswald acted alone. Opinion polls and the media debate showed the lack of consensus concerning the historical truth about Kennedy's assassination. The wide range of disagreement, in general and over so many particulars, demonstrated both the absence of shared public knowledge and just how much of the account remains obscured in controversy and confusion.

This state of affairs made it all the more difficult to conceive of a film (or any other kind of project for that matter) on the assassination that would not be disputatious. Apart from Warren Commission apologists (considered by Stone "a dying breed"), the assassination remains an unresolved event. But even among the independent conspiracy researchers, who became Stone's primary source for information about the assassination, there was considerable dispute about what constituted reliable historical evidence and what was purely speculation.