Industrial Towns and Cities

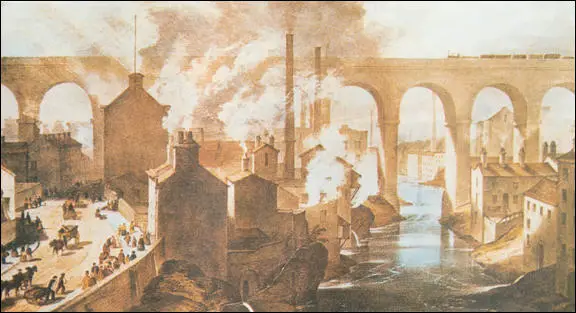

With the invention of the steam-engine, factories no longer had to be built by the side of fast-flowing rivers. Businessmen now tended to build factories where there was a good supply of labour. The obvious place to build a factory was therefore in a town.

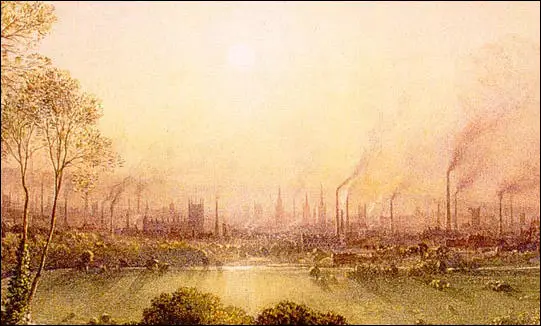

Manchester is a good example of how a town was changed by the Industrial Revolution. In 1773 Manchester was a market-town with a population of 27,000. Businessmen began building factories in the town because of Manchester's large population and local coal deposits. By 1802, Manchester had fifty-two textile factories and the population had grown to 95,000. (1)

Manchester and the Industrial Revolution

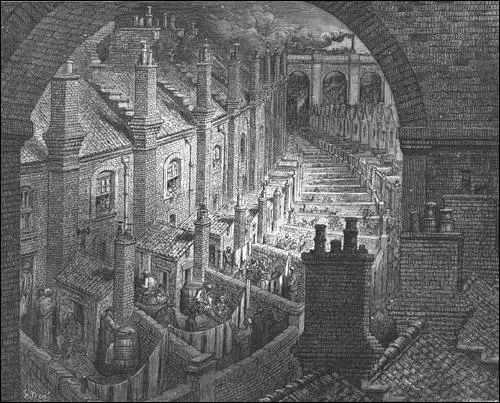

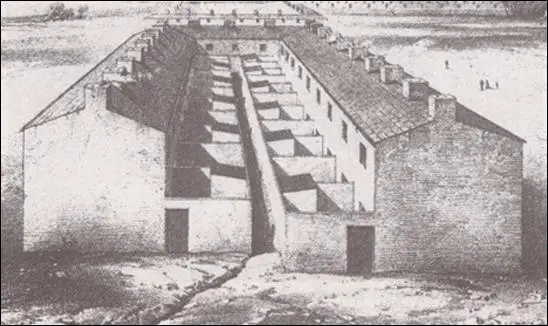

This attracted others who wanted to sell their goods and services to this large population. This caused further growth, and by 1851 the population of Manchester was over 300,000. The people who moved to towns such as Manchester needed somewhere to live. Builders realised that good profits could be made by quickly building cheap housing. One way of doing this was to make sure that the houses shared as many walls as possible. The result was rows and rows of back-to-back, terraced houses. The gaps between the rows were often as narrow as eight or nine feet.

The journalist, Henry Mayhew, argued that the government needed to know the scale of the problem that existed. He wrote a series of articles for the newspaper, The Morning Chronicle. He later described himself as a "social explorer" and saw his role "as supplying information concerning a very large body of persons, of whom the public had less knowledge than of the most distant tribes of the earth". (2) Another journalist, James Greenwood, who also investigated the problems of living in the new industrial towns saw himself as a "volunteer explorer in the depths of social mysteries". (3)

James P. Kay-Shuttleworth was a doctor in Manchester and in 1832 he reported: "Frequently, the inspectors found two or more families crowded into one small house and often one family lived in a damp cellar where twelve or sixteen persons were crowded. Children are ill-fed, dirty, ill-clothed, exposed to cold and neglect; and in consequence, more than one-half of the off-spring die before they have completed their fifth year. The strongest survive; but the same causes which destroy the weakest, impair the vigour of the more robust; and hence the children of our manufacturing population are proverbially pale and sallow." (4)

The large number of factories in Manchester caused a considerable amount of pollution. Alexis de Tocqueville was a French aristocrat who visited the city in 1835. "A sort of black smoke covers the city. The sun seen through it is a disc without rays. Under this half daylight 300,000 human beings are ceaselessly at work.... From this foul drain the greatest stream of human industry flows out to fertilize the whole world. From this filthy sewer pure gold flows. Here humanity attains its most complete development and its most brutish; here civilisation works its miracles, and civilised man is turned back almost into a savage." (5)

Growth of Cities

London was probably the most polluted city in England: "It was noon, and an exquisitely bright and clear spring day; but the view was smudgy and smeared with smoke. Clumps of building and snatches of parks looked through the clouds like dim islands rising out of the sea of smoke. It was impossible to tell where the sky ended and the city began; and as you peered into the thick haze you could, after a time, make out the dusky figures of tall factory chimneys plumed with black smoke; while spires and turrets seemed to hang midway between you and the earth, as if poised in the thick grey air." (6)

Houses were also severely overcrowded. Friedrich Engels was shocked when he visited Liverpool in the 1840s. "Liverpool, with all its commerce, wealth, and grandeur yet treats its workers with the same barbarity. A full fifth of the population, more than 45,000 human beings, live in narrow, dark, damp, badly ventilated cellar dwellings, of which there are 7,862 in the city. Besides these cellar dwellings there are 2,270 courts, small spaces built up on all four sides and having but one entrance, a narrow-covered passage-way, the whole ordinarily very dirty and inhabited exclusively by proletarians. In Bristol, on one occasion, 2,800 families were visited, of whom 46 per cent occupied but one room each. (7)

The conditions outside the homes were also extremely bad. There was no system of refuse collection and most people just dumped their rubbish in the streets. Working-class homes did not have inside lavatories and people therefore had to share communal privies. These privies were often just holes in the ground covered by a wooden shed. When the privies were not cleaned out on a regular basis, the cesspits overflowed and the sewage ran down the streets. According to a report carried out in Leeds: "The privies are invariably in a filthy condition, and often remain without the removal of any portion of filth for six months." (8)

A magazine published in October 1843 pointed out the problems experienced by the people of Edinburgh: "These streets are often so narrow that a person can step from the window of one house into that of its opposite neighbour, while the houses are piled so high, storey upon storey, that the light can scarcely penetrate into the court or alley that lies between. There are neither sewers or drains, nor even privies belonging to the houses. In consequence, all refuse, garbage, and excrements of at least 50,000 persons are thrown into the gutters every night, so that, in spite of all the street sweeping, a mass of dried filth and four vapous are created, which not only offend the sight and smell, but endanger the health of the inhabitants in the highest degree." (9)

Nottingham was another town that had changed dramatically. It had a population of about 10,000 in the middle of the 18th century and it was described as "a garden city, with well laid out houses, surrounded by orchards and gardens in the midst of parkland and open spaces". By 1831 the population had risen to about 50,000 but the people were packed into very much the same ground area as had been occupied a hundred years before. It was now "a chequer board of mean streets, alleyways and courts". (10)

This was supported by an official report published in 1845: "I believe that nowhere else shall we find so large a mass of people crowded into courts as in Nottingham... The courts are almost always approached through a low-arched tunnel of some 30 or 36 inches wide, about 8 feet high, and from 20 to 30 feet long... In these confined quarters, the refuse is allowed to accumulate... until it has acquired value as manure... It is common to find the privies open and exposed to the public gaze of the inhabitants... The houses are three stories high, side by side, back to back." (11)

The worst slums were in London. The journalist, Henry Mayhew, carried out an investigation into the problem in 1849. "By the last census return (1841) the metropolis covered an extent of nearly 45,000 acres, and contained upwards of two hundred and sixty thousand houses, occupied by one million eight hundred and twenty thousand souls, constituting not only the densest, but the busiest hive, the most wondrous workshop, and the richest bank in the world. A strange incongruous chaos of wealth and want - of ambition and despair - of the brightest charity and the darkest crime, where there is more feasting and more starvation, than on any other spot on earth - and all grouped round the one giant centre, the huge black dome, with its ball of gold looming through the smoke and marking out the capital, no matter from what quarter the traveller may come". (12)

In 1750 around a fifth of the population lived in towns of more than 5,000 inhabitants; by 1850 around three-fifths did. This caused serious health problems for working-class people. In 1840, 57% of the working-class children of Manchester died before their fifth birthday, compared with 32% in rural districts. (13) Whereas a farm labourer in Rutland had a life-expectancy of 38, a factory worker in Liverpool had an average age of death of 15. (14)

Wealth and Poverty

Friedrich Engels agreed with Mayhew that they rich and poor lived very close together but they rarely visited each other's territory: "Every great city has one or more slums, where the working-class is crowded together. True poverty often dwells in hidden alleys close to the palaces of the rich; but, in general, a separate territory has been assigned to it, where removed from the sight of the happier classes, it may struggle along as it can... A person may live in it for years, and go in and out daily without coming into contact with a working people's quarter... This arises from the fact... that the working-people's quarters are sharply separated from the sections of the city reserved for the middle-class." (15) Thomas Carlyle pointed out: "Wealth has accumulated itself into masses and poverty, also in accumulation enough, lies impassably separated from it; opposed, uncommunicating, like forces in positive and negative poles." (16)

Carrier Street was considered to be one of the worst places to live in London and was described as "an almost endless intricacy of courts and yards crossing each other, rendered the place like a rabbit-warren." (17) The people living in the street became so angry that they decided to write to The Times about their problems: "We live in muck and filth. We ain't got no privies, no dustbins, no drains, no water supplies, and no sewers in the whole place... We are living like pigs, and it ain't fair... We hope you will let us have our complaints put into your influential paper, and make the landlords... make our houses decent for Christians to live in." (18)

Obtaining clean water was a constant problem in industrial towns. Some people used buckets to collect rain-water. However, the air was so polluted that this water would soon turn black. "As we passed along the reeking banks of the sewer the sun shone upon a narrow slip of the water. In the bright light it appeared the colour of strong green tea, and positively looked as solid as black marble in the shadow - indeed it was more like watery mud than muddy water; and yet we were assured this was the only water the wretched inhabitants had to drink." (19)

George R. Sims was another journalist who urged the government to take action to improve living conditions. "I was the other day in a room occupied by a widow women, her daughters of seventeen and sixteen, her sons of fourteen and thirteen, and two younger children. Her wretched apartment was on the street level, and behind it was a common yard of the tenement. For this room, the widow paid four and sixpence a week; the walls were mildewed and steaming with damp; the boards as you trod upon them made the slushing noise of a plant spread across a mud puddle in a brickfield. Of all the evils arising from this one room system there is perhaps none greater than the utter destruction of innocence in the young. A moment's thought will enable the reader to appreciate the evils of it. But if it is bad in the case of a respectable family, how much more terrible is it when the children are familiarised with actually immorality." (20)

Thomas Carlyle wrote that England seemed an "enchanted" land that had been "cursed by the gods, flowing with wealth from improved agriculture and industrial invention" but had the terrible problem of poverty that such wealth had brought with it. "To whom, then, is this wealth of England wealth? Who is it that it blesses; makes happier, wiser, beautifuler, in any way better? We have more riches than any Nation ever had before; we have less good of them than any Nation ever had before. Our successful industry is hitherto unsuccessful; a strange success, if we stop here! In the midst of plethoric plenty, the people perish; with gold walls, and full barns, no man feels himself safe or satisfied." (21)

Primary Sources

(1) Alexis de Tocqueville, was a French aristocrat who visited Manchester in 1835.

The employers are helped by science, industry, the love of gain and English capital. Among the workers are men coming from a country where the needs of men are reduced almost to those of savages, and who can work for a very low wage, and so keep down the level of wages for the English workmen who wish to compete, to almost the same level. So there is the combination of the advantages of a rich and of a poor country; of an ignorant and an enlightened people; of civilisation and barbarism. So it is not surprising that Manchester already has 300,000 inhabitants and is growing at a prodigious rate.

(2) The Artisan Magazine (October, 1843)

These streets (in Edinburgh) are often so narrow that a person can step from the window of one house into that of its opposite neighbour, while the houses are piled so high, storey upon storey, that the light can scarcely penetrate into the court or alley that lies between. There are neither sewers or drains, nor even privies belonging to the houses. In consequence, all refuse, garbage, and excrements of at least 50,000 persons are thrown into the gutters every night, so that, in spite of all the street sweeping, a mass of dried filth and four vapous are created, which not only offend the sight and smell, but endanger the health of the inhabitants in the highest degree.

(3) Friedrich Engels, Condition of the Working Class in England (1844)

Liverpool, with all its commerce, wealth, and grandeur yet treats its workers with the same barbarity. A full fifth of the population, more than 45,000 human beings, live in narrow, dark, damp, badly ventilated cellar dwellings, of which there are 7,862 in the city. Besides these cellar dwellings there are 2,270 courts, small spaces built up on all four sides and having but one entrance, a narrow-covered passage-way, the whole ordinarily very dirty and inhabited exclusively by proletarians. In Bristol, on one occasions, 2,800 families were visited, of whom 46 per cent occupied but one room each.

(4) In 1840, Dr. Robertson wrote a letter to his MP describing the housing conditions in Manchester.

The factories have sprung up along the watercourses, which are the rivers Irk, Irwell and Medlock, and the Rochdale Canal, and the dwellings of the work-people have kept increasing close to the factories. The interest and convenience of individual manufacturers... has determined the growth of the town and the manner of that growth, while the comfort, health and happiness of the inhabitants have not been considered.

(5) Dr. James P. Kay-Shuttleworth, The Moral and Physical Condition of the Working Classes in Manchester (1832)

Frequently, the inspectors found two or more families crowded into one small house and often one family lived in a damp cellar where twelve or sixteen persons were crowded. Children are ill-fed, dirty, ill-clothed, exposed to cold and neglect; and in consequence, more than one-half of the off-spring die before they have completed their fifth year. The strongest survive; but the same causes which destroy the weakest, impair the vigour of the more robust; and hence the children of our manufacturing population are proverbially pale and sallow.

(6) Friedrich Engels, Condition of the Working Class in England (1844) page 39

Every great city has one or more slums, where the working-class is crowded together. True poverty often dwells in hidden alleys close to the palaces of the rich; but, in general, a separate territory has been assigned to it, where removed from the sight of the happier classes, it may struggle along as it can... A person may live in it for years, and go in and out daily without coming into contact with a working people's quarter... This arises from the fact... that the working-people's quarters are sharply separated from the sections of the city reserved for the middle-class.

(7) J. R. Martin, Sanitary Report on Nottingham (1845)

I believe that nowhere else shall we find so large a mass of people crowded into courts as in Nottingham... The courts are almost always approached through a low-arched tunnel of some 30 or 36 inches wide, about 8 feet high, and from 20 to 30 feet long... In these confined quarters, the refuse is allowed to accumulate... until it has acquired value as manure... It is common to find the privies open and exposed to the public gaze of the inhabitants... The houses are three stories high, side by side, back to back.

(8) James Smith, Sanitary Report on Leeds (1845)

The most unhealthy parts of Leeds are the closed squares of houses which have been erected for working people.... The ashes, garbage, and filth of all kinds are thrown from the doors and windows of the houses upon the surface of the streets and courts... The privies are invariably in a filthy condition, and often remain without the removal of any portion of filth for six months.

(9) On 3 July, 1849, The Times published a letter from a group of people living in Carrier Street, London.

We live in muck and filth. We ain't got no privies, no dustbins, no drains, no water supplies, and no sewers in the whole place... We are living like pigs, and it ain't fair... We hope you will let us have our complaints put into your influential paper, and make the landlords... make our houses decent for Christians to live in.

(10) Thomas Carlyle, Past and Present (1843)

To whom, then, is this wealth of England wealth? Who is it that it blesses; makes happier, wiser, beautifuler, in any way better? We have more riches than any Nation ever had before; we have less good of them than any Nation ever had before. Our successful industry is hitherto unsuccessful; a strange success, if we stop here! In the midst of plethoric plenty, the people perish; with gold walls, and full barns, no man feels himself safe or satisfied.

(11) George R. Sims, How the Poor Live (1889)

I was the other day in a room occupied by a widow women, her daughters of seventeen and sixteen, her sons of fourteen and thirteen, and two younger children. Her wretched apartment was on the street level, and behind it was a common yard of the tenement. For this room, the widow paid four and sixpence a week; the walls were mildewed and steaming with damp; the boards as you trod upon them made the slushing noise of a plant spread across a mud puddle in a brickfield.

Of all the evils arising from this one room system there is perhaps none greater than the utter destruction of innocence in the young. A moment's thought will enable the reader to appreciate the evils of it. But if it is bad in the case of a respectable family, how much more terrible is it when the children are familiarised with actually immorality.

It is my shutting our eyes to evils that we allow them to continue unreformed for so long. I maintain that such cases as these are fit ones for legislative protection. The State should have the power of rescuing its future citizens from such surroundings, and the law which protects young children from practical hurt should also be so framed as to protect them from moral destruction.

It is better that the ratepayers should bear a portion of the burden of new homes for the respectable poor than that they should have to pay twice as much in the long-run for prisons, lunatic asylums and workhouses.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)