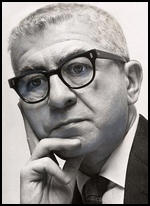

Herbert Aptheker

Herbert Aptheker was born in Brooklyn on 31st July, 1915. When he was 16 he went with his father to Alabama. He was shocked by the operation of the Jim Crow Laws and on his return to New York City he wrote an article for his school newspaper about racial segregation in the south.

Aptheker was educated at Columbia University and after he received a degree in 1936 he worked as an educational worker for the Food and Tobacco Workers Union. He joined the American Communist Party and also served as secretary of the Abolish Peonage Committee. In 1943 he published American Negro Slave Revolts.

Aptheker later admitted: "I studied history to attempt to solve a series of political problems. When I was an undergraduate, I chose history as a discipline that would allow me to look at social movements in the most holistic way... So I went to graduate school to study history not to be a history professor, but to be a professional Communist. That was my thing, and I was a member of the Communist Workers' Party."

During the Second World War he served in the United States Army and took part in Operation Overlord and by 1945 had reached the rank of major. He was editor of Masses and the Mainstream (1948-53) and in 1951 he published the first volume of a Documentary History of the Negro People in the United States.

Aptheker suffered from the effects of McCarthyism and was unable to obtain a full-time appointment as a university lecturer in the 1950s. On one occasion he was denied the right to speak at the Ohio State University and so while he sat in silence on the stage, students read from some of his writings. During this period he was editor of Political Affairs and served as executive director of the American Institute for Marxist Studies. He also published Laureates of Imperialism (1954) and The Era of McCarthyism (1955).

In 1957 Aptheker published the polemical, The Truth about Hungary. This attempt to justify the Red Army suppression of the Hungarian Uprising came under attack for being Soviet propaganda. One of his researchers, Anthony Flood, later commented: "He defended, against the sensibilities of even most American Communists, the Soviet invasion of Hungary and crushing of the revolt of its slaves. A refrain in Aptheker’s writings is that partisanship with oppressors is a reason to suspect the suppression of truth. Tragically, he did not see that precept’s relevance to the reception of his own scholarship."

As his biographer, Fred Whitehead, has pointed out: "From the beginning of his career, Aptheker has been devoted to Afro-American history. This included several volumes of his Documentary History of the Negro People. Colonial Times to 1910 appeared in 1959. This was followed by Reconstruction Years to the Founding of the NAACP, Beginning of the New Deal to the End of the Second World War and Alabama Protests to the Death of Martin Luther King Jr.

After the lifting of the blacklist Aptheker held posts at Bryn Mawr College, the University of California, City University of New York and the University of Santa Clara. During this period he was one of the main leaders of the opposition to the Vietnam War. Aptheker also edited the correspondence of William DuBois.

Other books by Aptheker included Nature of Democracy, Freedom and Revolution (1968),World of C. Wright Mills (1976), Unfolding Drama (1979), Afro-American History: the Modern Era (1986), American Revolution,1763-1783: A History of the American People (1987), Abolitionism: a Revolutionary Movement (1989), The Literary Legacy of W.E.B. DuBois (1989), Early Years of the Republic 1783-1793 (1989) and Anti-Racism in US History (1992).

Herbert Aptheker died 17th March, 2003.

Primary Sources

(1) Herbert Aptheker, American Negro Slave Revolts (1943)

Probably the most fateful year in the history of American Negro slave revolts is that of 1800, for it was then that Nat Turner and John Brown were born, that Denmark Vesey bought his freedom, and it was then that the great conspiracy named after Gabriel, slave of Tomas H. Prosser of Henrico Country, Virginia, occurred.

This Gabriel, the chosen leader of the rebellious slaves, was a 24-year-old giant of six feet two inches, “a fellow of courage and intellect above his rank in life,” who had intended “to purchase a piece of silk for a flag, on which they would have written ‘death or liberty.’”

Another leader was Jack Bowler, four years older and three inches taller than Gabriel, who felt that “we had as much right to fight for our liberty as any men.”

Gabriel’s wife, Nanny, was active, too, as were his brothers, Solomon and Martin. The former conducted the sword-making, and the latter bitterly opposed all suggestion of delaying the outbreak, declaring, “Before he would any longer bear what he had borne, he would turn out and fight with his stick.”

The conspiracy was well-formed by the spring of 1800, and there is a hint that wind of it early reached Governor Monroe, for in a letter to Thomas Jefferson, dated April 22, he referred to “fears of a negro insurrection.”

Crude swords and bayonets as well as about 500 bullets were made by the slaves through the spring, and each Sunday Gabriel entered Richmond, impressing the city’s features upon his mind and paying particular attention to the location of arms and ammunition.

Yet, as Callender wrote, it was “kept with incredible secrecy for several months,” and the next notice of apprehensions of revolt appears in a letter of Aug. 9 from Mr. J. Grammer of Petersburg to Mr. Augustine Davis of Richmond.

This letter was given to the distinguished Dr. James McClurg, who informed the military authorities and the governor. The next disclosure came during the afternoon of Saturday, Aug. 30, set for the rebellion and was made by Mr. Mosby Sheppard, whose slaves, Tom and Pharoah, had told him of the plot.

Monroe, seeing that speed was necessary and secrecy impossible, acted quickly and openly. He appointed three aides for himself, asked for and received the use of the federal armory at Manchester, posted cannon at the capitol, called into service well over 650 men and gave notice of the plot to every militia commander in the state.

“But,” as a contemporary declared, “upon that very evening just about sunset, there came on the most terrible thunder accompanied with an enormous rain, that I ever witnessed in this state. Between Prosser’s and Richmond, there is a place called Brook Swamp, which runs across the high road, and over which there was a ... bridge. By this, the Africans were of necessity to pass, and the rain had made the passage impracticable.” Nevertheless, about 1,000 slaves, some mounted, armed with clubs, scythes, home-made bayonets and a few guns, did appear at an agreed-upon rendezvous six miles outside the city, but, as already noted, attack was not possible, and the slaves disbanded. As a matter of fact even defensive measures, though attempted, could not be executed.

The next few days the mobilized might of an aroused slave state went into action and scores of Negroes were arrested. Gabriel had attempted to escape via a schooner, Mary, but when in Norfolk on Sept. 25, he was recognized and betrayed by two Negroes, captured and brought back, in chains, to Richmond.

(2) Herbert Aptheker, Walter Lippmann and Democracy (1955)

Back in 1933, the editors of The Nation, in introducing a series of four articles devoted to Walter Lippmann, remarked that he was "probably the most influential American journalist of our time." A similar estimate is true for our own day both in terms of the extensive audience reached by his columns (they appear in about 140 U.S. newspapers, 17 Latin American, 9 Canadian, and in Australian, Greek, Japanese and other papers throughout the world) and in terms of the special seriousness with which so much of his audience studies his opinions.

This year there has appeared Mr. Lippmann's twentieth book, Essays in The Public Philosophy, (Little, Brown) which for weeks has been among the nation's best-sellers, and reached additional thousands through nearly complete re-publication in a single issue of the reactionary organ, United States News & World Report, and in several issues of the liberal Atlantic Monthly. This offers a good occasion for a critical evaluation of the work of Mr. Lippmann.

In the extensive literature about Walter Lippmann a recurrent theme is his alleged ambiguity. One repeatedly finds such questions as those posed a generation ago by Amos Pinchot: "Has he the liberal and democratic view, or... is he the prophet... of big-business fascism?" The simultaneous publication of extracts from his latest book in the Atlantic on the one hand and U. S. News on the other, indicates the same quality, as do the book's reviews by two writers in the New Republic who find opposite lessons.

The same duality appears in Max Freedman's review of The Public Philosophy in The Nation. He begins by saying: "Few things would be easier than to caricature this book and make out that Walter Lippmann is an enemy of the democratic tradition." Easier or not, Mr. Freedman feels it best "to take Mr. Lippmann at his own evaluation" and for this he quotes Lippmann as saying, early in the volume: "I am a liberal democrat... " Yet, before Mr. Freedman is half through with his own review, he is discussing Lippmann's "condemnation of the democratic process" - peculiar conduct for a liberal democrat who is a friend of the democratic tradition.

Related to this apparent duality is another striking feature of the literature concerning Lippmann. Since the day, over thirty years ago, that Mr. Lippmann left the then very young New Republic to join the editorial staff of the New York World to the day of the appearance of his latest volume, writers have commented upon what they described as Lippmann's change in what had been liberal or even radical views. Mr. Lippmann is forever the "former liberal."

A generation ago, his New Republic colleague, Herbert Croly reported a Lippmann shift and attributed it to "unpardonable opportunism"; and just the other day, R. H. S. Crossman headed his piece on The Public Philosophy, "Mr. Lippmann Loses Faith." In this case the Lippmann shift was attributed to the "snapping of his patience" after years of "throwing the pearls of his expertise before the swine of a vast syndicated readership" (New Statesman & Nation, June 11, 1955). Others, including Carl Friedrich, Heinz-Eulau and Max Lerner, have offered varying explanations": for what they have viewed at different times as sharp changes in Lippmann's position...

We shall not enter into the game of guessing Mr. Lippmann's motivations because we do not know him or them; because we are interested in his ideas, not his psyche; and because, therefore, his personal motivations are irrelevant to our inquiry.

We have, however, indicated the prevalence and range of the guessing to show the nearly unanimous assumption that notable inconsistency has marked Mr. Lippmann's career. This, we think, is wrong. Mr. Lippmann, with the exception of his extreme youth, has always been anti-democratic; his latest book confirms and sharpens his anti-democratic outlook. (This point is made in the discerning review of The Public Philosophy by Prof. H.H. Wilson, in I.F. Stone’s Weekly, June 27, 1955.) This is said despite Lippmann's insistence in the book that he is "a liberal democrat" and despite Mr. Freedman's warning that such a characterization as I have offered is actually a caricature of the man's views. It is not a caricature. Mr. Lippmann is, and has been for at least thirty years, a systematic opponent of democracy because he has been a principled proponent of monopoly capitalism.

It is true, of course, that Lippmann's banner has fluttered with the breeze - and nearly bowed to an occasional storm but the heart of the matter is that even his semantically most liberal works contain an anti-democratic essence. For the past generation and more this essence has been scantily disguised; with The Public Philosophy, issued in the midst of a "New Conservatism" upsurge, the essence is distilled and boldly presented.

(3) Anthony Flood, The Journal of American History (September 2000)

In The Truth about Hungary the theoretician of “partisanship and objectivity” vilified Hungarian freedom fighters as fascists. In a similar vein he wrote Czechoslovakia and Counterrevolution. Again, about this side of his subject Kelly apparently doesn’t know or doesn’t care.

Common sense suggests that while uprisings may come from oppression, extreme oppression may make them impossible. Aptheker, however, interpreted their absence under Communism as evidence of democracy, their presence proof of foreign meddling. Should historians ignore this when they appraise his work on slave uprisings?

Aptheker now confesses that his lifelong allegiance to Communist regimes stemmed from a “denial of reality” that blocked out “monstrous crimes” of repression, “mass murder,” and “massive human extermination.” He has renounced his own Communist holocaust denial. His admirers do him no service by evading it.

(4) Herbert Aptheker, The Journal of American History (March 2001)

Mr. Flood's ignorance is matched by his malice. I will comment on one manifestation of both—the ignorance.

I suggest he read my study of the 1956 Hungarian events, now that he has denounced it. The Communist Party would not publish it; something ironically called the Liberal Press would not print it, despite offers to meet the cost.

The workers at the Hungarian-language paper, published in New York, finally printed it. Proof-reading was quite onerous! I have reread it recently and still am not ashamed of it - all the circumstances considered.

(5) Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, New York Times (20th March, 2003)

Herbert Aptheker, the prolific Marxist historian best known for his three-volume ''Documentary History of the Negro People in the United States'' and for editing the correspondence and writing of his mentor, W. E. B. DuBois, died on Monday in Mountain View, Calif. He was 87.

Along with his work on black history and his outspoken defense of civil rights, he was known as a dominant voice on the American left in the 1950's and 60's and as one of the first scholars to denounce American military involvement in Vietnam. His political views, and particularly a fact-finding trip to Hanoi and Beijing in 1966, resulted in threats by Washington to revoke his passport, a move that provoked a high-profile debate about the legality of State Department travel restrictions.

In another public feud, Mr. Aptheker took on the author William Styron, after the publication of his best-selling 1967 novel ''The Confessions of Nat Turner,'' a re-creation of the 1831 Virginia slave insurrection. Mr. Aptheker, as well as some black writers and historians, accused Mr. Styron of distorting the record and promoting racial stereotypes. Mr. Styron, who called his book a ''meditation on history,'' hotly rejected Mr. Aptheker's view, saying it was tainted by politics.

Although he wrote, taught and lectured widely on his political views, his only major attempt at elective office was an unsuccessful campaign for the House of Representatives from Brooklyn in 1966 on the Peace and Freedom ticket.

Among his lasting contributions was the editing of the DuBois letters. Writing in The New York Times Sunday Book Review, the historian Eric Foner called ''The Correspondence of W. E. B. DuBois'' (Massachusetts, 1973-1978) ''a landmark in Afro-American history.'' Yet when DuBois appointed Mr. Aptheker his literary executor in 1946 and subsequently turned over to him his vast correspondence shortly before his death in 1963, the move was vocally criticized in the black intellectual community.

Some felt that as a white man Mr. Aptheker could not truly identify with the black American experience. Others thought that for DuBois to have chosen an avowed Marxist to edit his papers was to make him vulnerable to the accusation, often voiced in the McCarthy era, that he himself was opposed to the American way of life.

Yet Mr. Aptheker's editing was greeted with wide praise. Reviewers said that his own extensive writing on African-American history had clearly prepared him for the task. Jay Saunders Redding, the black author and teacher, wrote in Phylon, a journal founded by DuBois, that ''what gives a special importance to the letters it contains is the light they shed on the why and how of this history and on the men and women who made it.''

(6) Anthony Flood, unpublished letter to the New York Times (March 2003)

Christopher Lehmann-Haupt’s March 20 obituary of Herbert Aptheker contains several errors of commission and omission.

Aptheker’s Documentary History of the Negro People in the United States runs to seven volumes, not three. He edited and annotated three volumes of W.E.B. Du Bois’ correspondence and 40 volumes of his published writings, including a 600-page annotated bibliography.

The obituary fails to mention that Aptheker’s 1937 Master’s thesis was about Nat Turner’s 1831 slave revolt and written on the basis of primary source research. This should be considered when weighing William Styron’s accusation that only politics motivated Aptheker’s criticism of his novel.

The title of Aptheker’s Columbia dissertation was American Negro Slave Revolts and chosen for its assonance with that of Ulrich Bonnell Phillips’ American Negro Slavery, to whose characterization of slaves the dissertation was opposed. By February 12, 1942, when Aptheker enlisted in the Army, he had completed almost all of the requirements for his doctorate: the awarding of the degree was contingent upon the dissertation’s being published, which it was the following year.

Yale University’s History Department sparked a controversy in 1976 when it refused to sponsor Aptheker’s seminar on Du Bois. The reason for the refusal, articulated by Yale Professor C. Vann Woodward, was not that Aptheker was a Communist, but that he “did not measure up to the standard of scholarship desired for teachers at Yale.” But as Aptheker lamented at the time, “If I’m not qualified to teach Du Bois, what am I qualified to teach?” Yale’s scholarly standards were apparently no barrier to Howard Cosell who taught “Big Time Sports and Contemporary America” during the same semester.

Aptheker’s run for a congressional seat in 1966 was not “his only major attempt at elective office,” for he lost to Daniel Patrick Moynihan in New York’s senatorial race a decade later. Aptheker later joked that the F.B.I. was still looking for the 25,000 people who voted for him.

Aptheker’s military career is summarized, but not its inglorious end. After Aptheker declined to answer the Army’s November 6, 1950 letter to him recounting his political activity over the previous decade, his commission in the Army reserves was summarily revoked on December 28. Not listed in the Army’s litany of political offenses, however, was Aptheker’s public support of Communist North Korea in its violent conflict with South Korea and the United States, in whose Army he had held the rank of Major and Instructor at the War College only a few years before.

The obituary gives the impression that Aptheker’s communist politics was all about racial equality, anti-fascism, and dissent from American foreign policy. But one of the books of which, to the very end of his life, he was most proud of having written was The Truth about Hungary in 1956. There he defended, against the sensibilities of even most American Communists, the Soviet invasion of Hungary and crushing of the revolt of its slaves.

A refrain in Aptheker’s writings is that partisanship with oppressors is a reason to suspect the suppression of truth. Tragically, he did not see that precept’s relevance to the reception of his own scholarship.