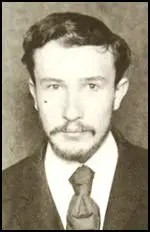

Boris Savinkov

Boris Savinkov, the son of a judge, was born in Kharkov on 19th January, 1879. A socialist, he became a law student at St. Petersburg University but was expelled in 1899 because of his political activities. Savinkov studied in Berlin and Heidelberg but on his return he was arrested in 1901 and sent into exile to Vologda, where he associated with left-wing intellectuals such as Anatoly Lunacharsky.

In 1903 Savinkov escaped abroad and joined the Socialist Revolutionary Party. He had rejected Marxism and now advocated of armed terrorism. When Gregory Gershuni was arrested, Yevno Azef, replaced him as the head of the SR Combat Organization. Savinkov, was appointed as his deputy.

Azef was also working for Okhrana and had been responsible for Gershuni's arrest. To avoid suspicion he decided to plan the assassination of Vyacheslav Plehve, the Minister of the Interior. Edward H. Judge, the author of Plehve: Repression and Reform in Imperial Russia (1983), has argued: "Azef sat in a very dangerous position, especially after Gershuni's arrest, and he had to think first of his own safety. A continual series of arrests, and a long train of assassination attempts gone awry, could only help convince his SR colleagues that they had a traitor in their midst. If he were found out, his game would be over, and so, most probably, would be his life. On the other hand, if he could successfully plan and accomplish the murder of Plehve, his position among the SRs would be secured. Azef had little love for Plehve: as a Jew, he could not help but resent the Kishinev pogrom and the minister's reputed role."

Plehve was killed by a bomb on 28th July, 1904. Praskovia Ivanovskaia who took part in the conspiracy later pointed out: "The conclusion of this affair gave me some satisfaction - finally the man who had taken so many victims had been brought to his inevitable end, so universally desired." Boris Savinkov was arrested and charged with being involved in the assassination. He was sentenced to death but managed to escape from his prison cell in Odessa.

Several members of the police leaked information to the leadership of the Socialist Revolutionary Party about the undercover activities of Yevno Azef. However, they refused to believe the stories and assumed the secret service was trying to undermine the success of the terrorist unit. Eventually a police defector managed to persuade them Azef was a police spy. When Azef heard the news he escaped to Germany. Savinkov now became head of the SR Combat Organization but was at this time a fairly ineffective organization.

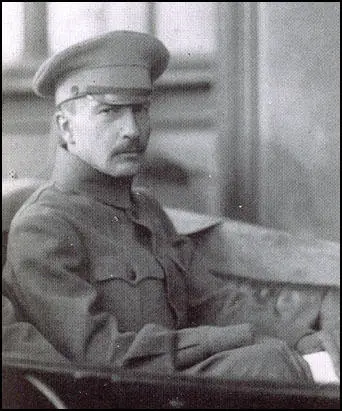

After the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II in March, 1917, George Lvov was asked to head the new Provisional Government in Russia. One of the first announcements made by Lvov was that all political exiles were allowed to return to their homes. Savinkov returned and in July became Deputy War Minister under Alexander Kerensky. According to Robin Bruce Lockhart, the son of Robert Bruce Lockhart, a British diplomat in Russia: "Savinkov was in his forties. A small dark man, slightly bald, he was a heavy smoker and a morphine addict... His enemies branded him a coward who showed courage only under the influence of drugs. It was said of him that although he had organized thirty-three assassination plots, including the murder of the Tsar's uncle, the Grand Duke Serge, he had never dared throw a bomb himself."

During this period Savinkov was introduced to Somerset Maugham, a British intelligence agent. Maugham described Savinkov as "the most remarkable man I met." He found it difficult to believe that Savinkov had been personally responsible for the assassination of a number of senior imperial officials in the years before the war. Maugham wrote, he had the prosperous look of a lawyer." Savinkov believed that if the Bolsheviks gained power they would "annihilate" opposition leaders. Savinkov therefore wanted the government to arrest Lenin and other leading Bolsheviks: "Either Lenin will stand me up in front of a wall and shoot me or I shall stand him in front of a wall and shoot him."

Savinkov resigned from the government on 30th August and was expelled from the Socialist Revolutionary Party due to his role in the uprising of General Lavr Kornilov in September 1917. Savinkov remained in Russia after the Lenin gained power. He established the Society for the Defence of the Motherland and Freedom and attempted to organise an armed uprising against the Bolsheviks. The union, which had a membership of approximately 5,000, had branches in several cities. It was supported financially by Western governments hostile to the Russian Revolution.

In July 1918 Savinkov fled to France, He was a strong supporter of Admiral Alexander Kolchak and became his diplomatic representative in Paris. The following year he moved to Poland where he supported the White Army in its struggle with the Red Army. He also published For Freedom! In the summer of 1921 Savinkov joined with Sidney Reilly to organize a secretly convened Anti-Bolshevik Congress in Warsaw to which delegates with differing shades of political opinion were invited. Savinkov was President of the Congress but most of the delegates were Socialist Revolutionary Party.

Savinkov was eventually expelled from Poland as a result of the anti-Bolshevik forces being defeated in the Russian Civil War. Savinkov arrived in London and began working with the Monarchist Union of Central Russia (also known as "The Trust"). Although it appeared to be an anti-Bolshevik organisation, according to Christopher Andrew & Vasili Mitrokhin, the authors of The Mitrokhin Archive (1999), it had been "invented by" Artur Artuzov of Cheka "in 1921 and used as the basis of a six-year deception."

As Richard Deacon, the author of A History of the Russian Secret Service (1972) pointed out: "Boris Savinkov... was given to understand that all the plotters inside Russia were waiting for was an assurance of massive support from the anti-Bolsheviks outside Russia. Soon Savinkov's own agents were being smuggled in and out of Russia." Savinkov asked Sidney Reilly to carry out investigations into "The Trust". Reilly contacted Ernest Boyce, the head of the Russian section of MI6. Boyce confirmed that the organization was apparently a movement of considerable power within Russia. Its agents had supplied valuable intelligence to the Secret Services of a number of anti-Bolshevik countries and was convinced that it was not under the control of Russian Secret Service.

Reilly now contacted Winston Churchill, who he knew was a passionate supporter of intervention, and told him that Savinkov was the best man to coordinate an overthrow of the Bolsheviks. Reilly arranged for Churchill to meet Savinkov. Churchill agreed that that Savinkov was a man of greater stature than any of the other Russian expatriates and that he was the only man who might organize a successful counter-revolution. Prime Minister David Lloyd George had doubts about trying to overthrow the Bolsheviks: "Savinkov is no doubt a man of the future but I need Russia at the present moment, even if it must be the Bolsheviks. Savinkov can do nothing at the moment, but I am sure he will be called on in time to come. There are not many Russians like him."

The Foreign Office was unimpressed with Savinkov describing him as "most unreliable and crooked". Churchill replied that he thought that he "was a great man and a great Russian patriot, in spite of the terrible methods with which he has been associated". Churchill rejected the advice of his advisors on the grounds that "it is very difficult to judge the politics in any other country". With the agreement with Mansfield Smith-Cumming, the head of MI6, it was decided to send Savinkov back into Russia. Richard Deacon has argued that "It was not that he (Savinkov) did not realise there was a risk of deception, but that he had become desperate in his quest for a solution to the problem of defeating the Bolsheviks. His impatience caused him not merely to take a cautious gamble but to risk his life in the cause of counter-revolution."

On 10th August 1924, Savinkov left for Russia. Nineteen days later Izvestia announced that Savinkov had been arrested. Over the next few months the newspaper announced that he had been condemned to death; sentence had been commuted to ten years' imprisonment and finally released. It was reported that he was living in a comfortable house in Loubianka Square. Savinkov wrote to Sidney Reilly, that he had changed his views of the Bolsheviks: "How many illusions and fairy tales have I buried here in the Loubianka! I have met men in the GPU whom I have known and trusted from my youth up and who are nearer to me than the chatter-boxes of the foreign delegation of the Social-Revolutionaries... I cannot deny that Russia is reborn."

Reilly believed the letter had been written by the GPU. A long letter appeared in The Morning Post on 8th September, 1924: "I claim the great privilege of being one of his most intimate friends and devoted followers, and on me devolves the sacred duty of vindicating his honour. Contrary to the affirmation of your correspondent, I was one of the very few who knew of his intention to penetrate into Soviet Russia. On receipt of a cable from him, I hurried back, at the beginning of July, from New York, where I was assisting my friend, Sir Paul Dukes, to translate and to prepare for publication Savinkov's latest book, The Black Horse. Every page of it is illuminated by Savinkov's transcendent love for his country and by his undying hatred of the Bolshevist tyrants. Since my arrival here on July 19th, I have spent every day with Savinkov up to August 10th, the day of his departure for the Russian frontier. I have been in his fullest confidence, and all his plans have been elaborated conjointly with me. His last hours in Paris were spent with me."

Boris Savinkov died on 7th May, 1925. According to the government he committed suicide by jumping from a window in the Lubyanka Prison. However, other sources claim that he was killed in prison by agents of the All-Union State Political Administration (GPU). Sidney Reilly insisted that Savinkov was murdered in August 1924: "Savinkov was killed when attempting to cross the Russian frontier and a mock trial, with one of their own agents as chief actor, was staged by the Cheka in Moscow behind closed doors."

Primary Sources

(1) Victor Serge, Year One of the Russian Revolution (1930)

The SR Battle Organization was founded by Gregory Gershuni in 1902; its first act, in the same year, was the execution of the Minister of Education Sipyagin by the student Balmashev (who was later hanged). On the day after the murder, the SR party published under a similar verdict. The arrest of Gershuni, who was delivered to the police by Azef, caused the latter's promotion to the top leadership of the terrorist detachment. A man named Boris Savinkov, for whom terrorism was a vocation and whose courage was indomitable, now found himself under the orders of the agent-provacateur. In 1904 the Prime Minister, Plehve, fell mutilated by Sazonov's bomb. Sazonov had organized the assassination on instructions from Azef.

(2) Richard Deacon, A History of the Russian Secret Service (1972)

Ironically, the Soviet's arch enemy now was that former fiery and ruthless revolutionary, Boris Savonkov, the colleague of Azef, and for so many years the most dedicated and active supporter of revolution. Savonkov had come into his own as Minister for War under the Kerensky Government and had immediately thrown himself wholeheartedly into the task of giving the Russian people democratic government. For at heart Savonkov believed in democracy, in liberty and tolerance. It was for the establishment of these things as a permanent feature of Russian life that he had risked his life for a quarter of a century, assassinated, organised terrorist attacks and co-operated with killers. For him the end was greater than the means, but he soon found that for the Bolsheviks the end was merely the perpetuation of the means-terror as a permanent policy of holding down the people. So Savonkov the bomb-thrower and revolutionary became the hero of the White Russians and the most determined of counter-revolutionaries.

No ordinary man could have survived such a transition. That Savonkov did so and surprised his former enemies by his courage and integrity, and won the admiration of such men of other nations as Winston Churchill and Marshal Pilsudski of Poland, was a tribute to his personality and his ability.

The loss of Savonkov from the revolutionary ranks was a serious blow to the Soviet. Dzerzhinsky said sadly that it was as though the Red Army had lost three divisions and he was personally as much disposed to win back Savonkov as to see him assassinated. The Soviet knew that if Savonkov could be detached from the counter-revolutionaries the White Russians' cause would collapse.

Nadel was consulted as to how a permanent watch could be kept on Savonkov"The only way to do it," he reported back to Moscow, "would be to control the man who keeps Savonkov supplied with morphine." The fatal vice of the former revolutionary was that he was addicted to morphine, a drug he had taken to keep up his courage in his days as a terrorist. From the moment Dzerzhinsky received this advice he decided that Savonkov must either be kidnapped, or lured back to Russia where morphine would be given to him, or withheld according to the degree to which he agreed to co-operate with the Soviet authorities.

Kidnapping was ruled out on two points: first, it would remove Savonkov, but not necessarily destroy his cause; secondly, in the current state of the Russian Secret Service, with so few trusted agents abroad, it was too difficult an operation to perform on foreign territory. Dzerzhinsky was also mindful of how Britain had seized Litvinoff as a hostage when he ordered Bruce Lockhart's arrest. Kidnapping, he suspected, would give any other Western power an excuse to copy Britain's example. So Dzerzhinsky planned a long-term operation to lure Savonkov and other prominent White Russians back to Moscow. If the world could be informed that these men had returned "voluntarily" to their fatherland, that would be a devastating blow to their cause.

(3) Giles Milton, Russian Roulette: How British Spies Thwarted Lenin's Global Plot (2013)

Maugham also had several meetings with Boris Savinkov, the feisty Minister of War. Here, at last, was someone with whom he could do business. He described Savinkov as "the most remarkable man I met."His fascination was due, in part, to the fact that Savinkov had been personally responsible for the assassination of a number of senior imperial officials in the years before the war. Maugham found it hard to picture such a genial individual killing people in cold blood. "He had," he wrote, "the prosperous look of a lawyer."

As the champagne flowed and the party grew increasingly merry, Maugham plucked up the courage to quiz Savinkov about the assassinations. "When I asked him if it wasn't rather nervous work, he laughed and said: "Oh, it's just business like another."

Savinkov was disarmingly frank when telling Maugham about the dangers posed by the Bolshevik revolutionaries. He warned that they were bent on annihilating all who did not share their radical views. "He said to me once in his casual way: "Either Lenin will stand me up in front of a wall and shoot me or I shall stand him in front of a wall and shoot him."

Maugham reported every detail of his conversations back to Wiseman in America. Wiseman, in turn, forwarded the information to Mansfield Cumming. As a precaution against the Germans intercepting these telegraphic messages, Maugham wrote in code, with special signifiers for each letter of the alphabet and previously agreed names for all the principal players.

(4) Richard Deacon, A History of the Russian Secret Service (1972)

It was Boris Savinkov who was the first to be inspired with confidence in "The Trust". He was given to understand that all the plotters inside Russia were waiting for was an assurance of massive support from the anti-Bolsheviks outside Russia. Soon Savinkov's own agents were being smuggled in and out of Russia.

Savinkov, with his long experience of revolutionary tactics, his own knowledge of the treachery of such agents provocateurs as Azef, should perhaps have been more wary of "The Trust". It was not that he did not realise there was a risk of deception, but that he had become desperate in his quest for a solution to the problem of defeating the Bolsheviks. His impatience caused him not merely to take a cautious gamble but to risk his life in the cause of counter-revolution. What appeared to have convinced Savinkov of the reliability of "The Trust" was the fact that the White Russian General, Kutyepoff, who had escaped to Finland, was a member of it. But by this time "The Trust" had won over many unsuspecting anti-Bolsheviks into its actual network: without realising it, they were being used to defeat their own eventual aims.

Those who saw Savinkov in these last days before he took his fatal decision were shocked at the change in the man. He was drugging himself heavily and it was obvious that somebody was actively encouraging him to do so. He was full of madly defiant schemes of action at one moment, deep in depression the next. Whether "The Trust" ensured that drugs should play a part in the breaking down of Savinkov one cannot be sure, but they knew from the dossier on Savinkov that under the influence of morphine he could be persuaded to perform deeds of quixotic daring. At any rate it was "The Trust" who persuaded him to return to Russia, give himself up and "confess" his "crimes" and announce that he supported the Soviet Government. But, he was assured, because he would make this renouncement of the White Russian cause, his life would be spared and he would be inside Russia ready to take over the reins of power the moment "The Trust" launched their counter-revolution.

Sidney Reilly suspected that Savinkov was being trapped and advised strongly against this crazy plan. But on 10 August 1924 Savinkov set off for Russia. Nineteen days later Izvestia announced that Savinkov had been arrested. Rumours persisted for days. First it was reported that Savinkov had been condemned to death, then came news that he had been completely acquitted and was free.

But the Russian version of Savinkov's return to his fatherland is somewhat different. This states that Reilly had approved of Savinkov's mission to Moscow, having changed his mind after he and Savinkov had failed in their attempt to engineer the assassination of Chicherin, the Soviet Foreign Minister, at The Hague. Indeed the Soviet version-and it is contained in the book Troubled Waters-is that Reilly actually paid for Savinkov's trip to Russia.

The report from Moscow of Savinkov's renunciation of the cause of the White Russians and his statement that he "honoured the power and wisdom of the G.P.U." shocked his supporters into silence and dealt a devastating blow to the counter-revolutionaries. Small news items given out by Izvestia seemed to confirm the worst suspicions that Savinkov had indeed betrayed his cause, and when Sidney Reilly received a letter from Savinkov stating that he had "met men in the G.P.U. whom I have known and trusted from my youth up and who are nearer to me than the chatter-boxes of the foreign delegation of the Social-Revolutionaries", this seemed the final straw.

Undoubtedly drugs had played havoc with Savinkov's state of mind and drugs were to be used by the G.P.U. finally to crush his spirit once he was safely in Russia. Savinkov had tried to play a devious game which he could not possibly win. But it is also possible that this letter, which the G.P.U. had allowed him to send, was a forgery. The Foreign Section of the G.P.U. had a special department known as Kaneva which spent their time forging letters and documents. Indeed, the Kaneva was not only an important adjunct of the I.N.O., but one of the most useful agencies the Soviet Secret Service possessed at this time for obtaining foreign currency with which to pay their spies. Kaneva was more a factory than an intelligence department, turning out forged documents by the score, and most of these were given to agents to take abroad and sell to foreign governments for pounds, dollars and, in some cases, French gold. The agents either posed as double-agents and sold to foreign espionage services, or sold the documents to foreign agents who then resold them at a profit.

Savinkov was not kept in prison, but confined to what was in effect comfortable house arrest in Loubianka Square. The G.P.U. needed to keep Savinkov alive in order that the outside world should be convinced of the fact that "The Trust" was still influential. Yet the very fact that the Soviet Government showed such mercy to Savinkov, who had long been on their "death list", should have put other counter-revolutionaries on their guard. Far from confirming that "The Trust" was dependable, it should have told them that that organisation was probably controlled by the G.P.U.

(5) Sidney Reilly, The Morning Post (8th September, 1924)

My attention has been drawn to the article, Savinkov's Nominal Sentence, published in the Morning Post of September 1st. Your informant, without adducing any proofs whatsoever and basing himself merely on rumours, makes the suggestion that Savinkov's trial was a "stunt" arranged between him and the Kremlin clique, and that Savinkov had already for some time contemplated a reconciliation with the Bolsheviks.

No more ghastly accusation could be so carelessly hurled against a man whose whole life has been spent fighting tyranny of whatsoever denomination, Tsarist or Bolshevist, and whose name all over the world has stood for "No Surrender" to the sinister powers of the Third International.

I claim the great privilege of being one of his most intimate friends and devoted followers, and on me devolves the sacred duty of vindicating his honour. Contrary to the affirmation of your correspondent, I was one of the very few who knew of his intention to penetrate into Soviet Russia. On receipt of a cable from him, I hurried back, at the beginning of July, from New York, where I was assisting my friend, Sir Paul Dukes, to translate and to prepare for publication Savinkov's latest book, The Black Horse. Every page of it is illuminated by Savinkov's transcendent love for his country and by his undying hatred of the Bolshevist tyrants. Since my arrival here on July 19th, I have spent every day with Savinkov up to August 10th, the day of his departure for the Russian frontier. I have been in his fullest confidence, and all his plans have been elaborated conjointly with me. His last hours in Paris were spent with me.

Nineteen days later came the news of his arrest, then in quick, almost hourly, succession, of his trial, his condemnation to death, the commutation of the death sentence to ten years' imprisonment, his complete acquittal, and finally his liberation.

Where are the proofs of all this phantasmagoria? What is the source of this colossal libel? The Bolshevist news agency Rosta!

It is not surprising that the statements of the Rosta, this incubator of the vilest Bolshevist canards, should be swallowed without demur, and even with joy, by the Communist press, but that the anti-Communist press should accept those palpable forgeries for good currency is beyond comprehension.

I am not yet in a position to offer you definite proofs of this Bolshevist machination to discredit Savinkov's good name; but permit me to call your attention to the following most significant facts:

1. The Rosta states that Savinkov was tried behind closed doors. We must assume that no correspondents of non-Communist European or American papers were present, otherwise the world would have already had their account of the proceedings.

2. The official Bolshevist journal, the Izvestia, up to August 28th, does not mention a single word about Savinkov. Is it likely that having on the 20th achieved such a triumph as the capture of their "greatest enemy" the Bolsheviks would pass over it in silence during an entire week?

3. What do all the so-called "sincere confessions and recantations" consist of? Of old political tittle-tattle which has been known for years to every European Chancery and also to the Bolsheviks, and has now been re-hashed for purposes of defamation and propaganda. Not a single new and really confidential fact as regards Savinkov's activities or relations with Allied statesmen during the last two years has come to light.

4. No confederates are either mentioned or implicated in the trial with Savinkov.

What are the inferences to be drawn from all the above facts? Savinkov was killed when attempting to cross the Russian frontier and a mock trial, with one of their own agents as chief actor, was staged by the Cheka in Moscow behind closed doors.

Need one mention the trials of the Social-Revolutionaries, of the Patriarch, of the Kiev professors, in order to remind the public of what unspeakable villainies the Bolsheviks are capable? For the moment they have succeeded in throwing a shadow on the great name of their admittedly most active and most implacable enemy. But the truth will penetrate even the murky darkness of this latest Cheka conspiracy, and will shine forth before the world...

Sir, I appeal to you, whose organ has always been the professed champion of anti-Bolshevism and anti-Communism, to help me vindicate the name and honour of Boris Savinkov.