California Trail

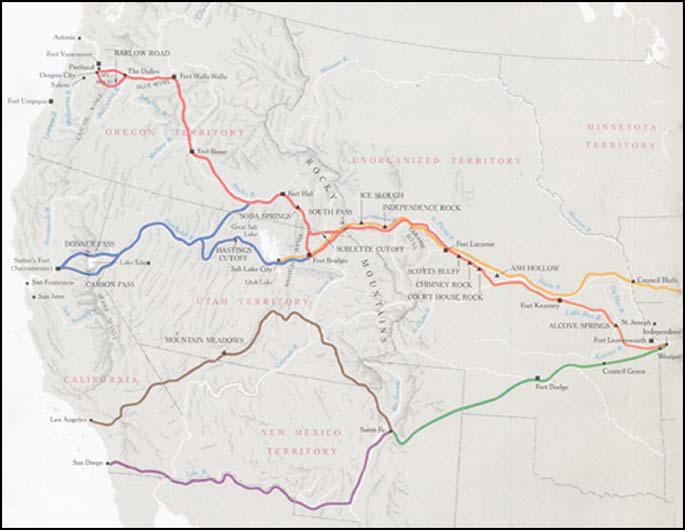

The route from the Missouri River to the Columbia River became known as the Oregon Trail. Part of this trail was covered by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark in 1805. Later it was used by mountain men and fur traders.

The trail began at Independence, Missouri and the first main stopping point was Fort Laramie. The next stop was Fort Bridger before the travellers used the South Pass to reach the Pacific side of the Rocky Mountains. After halting at Fort Hall the migrants crossed the Blue Mountains. The final stage of the journey was to follow the Umatilla River to Fort Vancouver, the terminus of the Oregon Trail. The entire journey was over 2,000 miles.

After the discovery of gold near Sutter Fort 1848 a growing number of migrants wanted to travel to California. This people followed the Oregon Trail until they reached Fort Bridger. The migrants left the trail at Fort Bridger and after crossing the Sierra Nevada headed for San Francisco.

In 1849 around 30,000 people used the California Trail. It is estimated that around 5,000 of these died on the journey. Overall, 150,000 people travelled overland from Missouri to California between 1850 and 1856.

Primary Sources

(1) Heinrich Lienhard, From St. Louis to Sutter's Fort, 1846 (1900)

We had already left the Little Blue and were getting closer to the Platte River. Gradually the luxuriant grass of the regions of the Kansas disappeared; the grass became shorter and was of a different kind. The night before we had camped not far from the Little Blue and hoped to reach the Platte during the day or early the next morning. Ripstein shouldered his rifle and said he wanted to go upstream along the Little Blue River. Maybe he would succeed in bagging a deer or an antelope. He would meet us again somewhere along the road. We warned him about the Indians, for we had been told that somewhere along the Little Blue there was a large camp of Pawnees, whose hostility toward the whites was generally feared. Ripstein was tall, courageous, and strong and an excellent runner, never seeming to tire.

We continued our journey at the usual time through the open prairie and were caught by dusk before coming in sight of the Platte River. Since we had some firewood with us, we made camp near several water holes, which were full of mosquitoes, though we could use the water for coffee and tea after straining it through a clean handkerchief.

(2) William Swain, letter written on the Trail to California (4th July 4, 1849)

We shall pass Fort Laramie tomorrow, where I shall leave this to be take to the States. It will probably be the last time I can write until I get to my journey's end, which may take till the middle of October.

We have had uncommon good health and luck on our route, not having had a case of sickness in the company for the last four weeks. Not a creature has died, not a wagon tire loosened, and no bad luck attended us.

The country is becoming very hilly; the streams rapid, more clear, and assuming the character of mountain streams. The air is very dry and clear, and our path is lined with wild sage and artemisia.

We had a fine celebration today, with an address by Mr. Sexton, which was very good; an excellent dinner, good enough for any hotel; and the boys drank toasts and cheered till they are now going in all sorts around the camp.

I often think of home and all the dear objects of affection there: of George; dear Mother, who was sick; and of yourself and poor little Sister. If it were consistent, I should long for the time to come when I shall turn my footsteps homeward, but such thoughts will not answer now, for I have a long journey yet to complete and then the object of the journey to accomplish.

I am hearty and well, far more so than when I left home. That failing of short breath which troubled me at home has entirely left me. I am also more fleshy. Notwithstanding these facts, I would advise no man to come this way to California.

(3) Luzena Wilson, Memoirs (1881)

Everything was at first weird and strange in those days, but custom made us regard the most unnatural events as usual. I remember even yet with a shiver the first time I saw a man buried without the formality of a funeral and the ceremony of coffining. We were sitting by the camp fire, eating breakfast, when I saw two men digging and watched them with interest, never dreaming their melancholy object until I saw them bear from their tent the body of their corade, wrapped in a soiled gray blanket, and lay it on the ground. Ten minutes later the soil was filled in, and in a short half hour the caravan moved on, leaving the lonely stranger asleep in the silent wilderness, with only the winds, the owls, and the coyotes to chant a dirge. Many an unmarked grave lies by the old emigrant road, for hard work and privation made wild ravages in the ranks of the pioneers, and brave souls gave up the battle and lie ther forgotten, with not even a stone to note the spot where they sleep the unbroken, dreamless sleep of death. There was not time for anything but the ceaseless march for gold.

There was not time to note the great natural wonders that lay along the route. Some one would speak of a remarkable valley, a group of cathedral-like rocks, some mineral springs, a salt basin, but we never deviated from the direct route to see them. Once as we halted near the summit of the Rocky Mountains for our "nooning", digging through three or four inches of soil we found a stratum of firm, clear ice, six or eight inches in thickness, covering the whole level space for several acres where our train had stopped. I do not think even yet I have ever heard a theory accounting for the strange sheet of ice lying hard and frozen in mid-summer three inches below the surface.

After a time the hard traveling and worse roads told on our failing oxen, and one day my husband said to me, "Unless we can lighten the wagon we shall be obliged to drop out of the train, for the oxen are about to give out." So we looked over our load, and the only things we found we could do without were three sides of bacon and a very dirty calico apron which we laid out by the roadside. We remained all day in camp, and in the meantime I discovered my stock of lard was out. Without telling my husband, who was hard at work mending the wagon, I cut up the bacon, tried out the grease, and had my lard can full again. The apron I looked at twice and thought it would be of some use yet if clean, and with the aid of the Indian soap-root, growing around the camp, it became quite a respectable addition to my scanty wardrobe. The next day the teams, refreshed by a whole day's rest and good grazing, seemed as well as ever, and my husband told me several times what a "good thing it was we left those things; that the oxen seemed to travel as well again".

(4) Luzena Wilson, Memoirs (1881)

Our long tramp had extended over three months when we entered the desert, the most formidable of all the difficulties we had encountered. It was a forced march over the alkali plain, lasting three days, and we carried with us the water that had to last, for both men and animals, till we reached the other side. The hot earth scorched our feet; the grayish dust hung about us like a cloud, making our eyes red, and tongues parched, and our thousand bruises and scratches smart like burns. The road was lined with the skeletons of the poor beasts who had died in the struggle. Sometimes we found the bones of men bleaching beside their broken-down and abandoned wagons. The buzzards and coyotes, driven away by our presence from their horrible feasting, hovered just out of reach. The night that we camped in the desert my husband came to me with the story of the "Independence Company". They, like hundreds of others had given out on the desert; their mules gone, many of their number dead, the party broken up, some gone back to Missouri, two of the leaders were here, not distant forty yards, dying of thirst and hunger. Who could leave a human creature to perish in this desolation? I took food and water and found them bootless, hatless, ragged and tattered, moaning in the starlight for death to relieve them from torture. They called me an angel; they showered blessings on me; and when they recollected that they had refused me their protection that day on the Missouri, they dropped on their knees there in the sand and begged my forgiveness. Years after, they came to me in my quiet home in a sunny valley in California, and the tears streamed down their bronzed and weather-beaten cheeks as they thanked me over and over again for my small kindness. Gratitude was not so rare a quality in those days as now.

It was a hard march over the desert. The men were tired out goading on the poor oxen which seemed ready to drop at every step. They were covered with a thick coating of dust, even to the red tongues which hung from their mouths swollen with thirst and heat. While we were yet five miles from the Carson River, the miserable beasts seemed to scent the freshness in the air, and they raised their heads and traveled briskly. When only a half mile of distance intervened, every animal seemed spurred by an invisible imp. They broke into a run, a perfect stampede, and refused to be stopped until they had plunged neck deep in the refreshing flood; and when they were unyoked, they snorted, tossed their heads, and rolled over and over in the water in their dumb delight. It would have been pathetic had it not been so funny, to see those poor, patient, overworked, hard-driven beasts, after a journey of two thousand miles, raise heads and tails and gallop at full speed, an emigrant wagon with flapping sides jolting at their heels. At last we were near our journey's end. We had reached the summit of the Sierra, and had begun the tedious journey down the mountain side. A more cheerful look came to every face; every step lightened; every heart beat with new aspirations. Already we began to forget the trials and hardships of the past, and to look forward with renewed hope to the future. The first man we met was about fifty miles above Sacramento. He had ridden on ahead, bought a fresh horse and some new clothes, and was coming back to meet his train. The sight of his white shirt, the first I had seen for four long months, revived in me the languishing spark of womanly vanity; and when he rode up to the wagon where I was standing, I felt embarrassed, drew down my ragged sun-bonnet over my sunburned face, and shrank from observation. My skirts were worn off in rags above my ankles; my sleeves hung in tatters above my elbows; my hands brown and hard, were gloveless; around my neck was tied a cotton square, torn from a discarded dress; the soles of my leather shoes had long ago parted company with the uppers; and my husband and children and all the camp, were habited like myself in rags.

(5) Heinrich Lienhard, From St. Louis to Sutter's Fort, 1846 (1900)

Finally, there appeared before our eyes several high, fenced enclosures (corrals) into which the cattle are driven, either to select them for slaughter or to brand them. And there was a house, too, with two beautiful young American females at the open window. This place belonged to a Scot named Sinclair, who held the position of justice of the peace. One of the women was his wife. This house was near the open banks of the smooth but wide American River, and since we could find no trace of a ferry, we waded through its clear but not deep waters. On the opposite bank we found ourselves on lowland, which is often entirely under water during the rainy season. Farther back from the river we reached higher and drier land, where we came upon a lone Indian sod-covered hut. A quarter of a mile to the left of the road we saw a fairly long, wide adobe structure, the walls of which contained many embrasure like openings. On the east were two small houses and a few steps farther on was a deep pond, which gets its water from the American Fork only during high water. This place was Sutler's sheepfold, with which I had ample opportunity to become acquainted two years later. The land over which the road led was considered unproductive at that time, but to our right not far from the road was a beautiful large piece of bottomland where Sutter had his wheat fields, which yielded magnificent harvests. After we had walked about a mile beyond the river, we saw from a slight elevation the long wished for Fort Sutter or New Helvetia.