Denys Wortman

Denys Wortman, the descendant of of early Dutch settlers, was born in Saugerties, New York, in 1887. Wortman studied under Robert Henri, at the New York School of Fine and Applied Art. Henri was an advocate of realism in art became the leader of a movement that Art Young described as the Ash Can School.

Robert Henri taught his students that the artist's work should be "a social force that creates a stir in the world". Henri also urged artists to use the "rich subject-matter provided by modern urban life". Wortman, like other artists taught by Henri, such as John Sloan, George Bellows, George Luks, Rockwell Kent and Edward Hopper were deeply influenced by his ideas.

Wortman's work appeared in the world famous Armory Show in New York City in 1913. Organized by the Association of American Painters and Sculptors, a group started by Robert Henri in 1911, the International Exhibition of Modern Art was held from 17th February to 15th March. It has been claimed that this event marked the beginning of the progressive art movement in the United States.

In 1924 Wortman began working for the New York World. His cartoons reflected Henri's views that artists should use the "rich subject-matter provided by modern urban life". His cartoons were particularly powerful during the Depression and many were reprinted in The Unemployed journal.

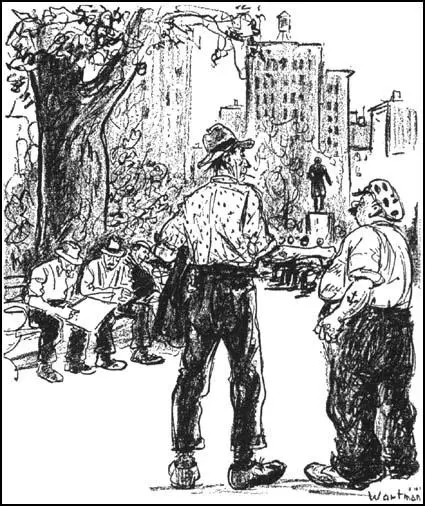

In February, 1931, the newspaper was sold to Edward Scripps organization and the New York Telegram. His most well-known characters were two vagrants, Mopey Dick and the Duke. His son, points out on the Denys Wortman Website that the artist's wife, Hilda Renbold Wortman, played an important role in these cartoons: "She would sit on park benches and listen to the conversations around her, reporting back to my father the phrases and conversations that she overheard. From these and other captions, he would create the image, the atmosphere and the surrounding that would communicate the idea visually."

Wortman also worked for Metropolitan Movies for thirty years. Denys Wortman, who retired from the New York Telegramin 1954, died at his home in Martha's Vineyard in 1958.

"Here, put this toothpick in your mouth, Mopey,

and the other guy's will think we had something to eat."

Denys Wortman, The Unemployed (1931)

Primary Sources

(1) Charles Hanson Towne, An Interpreter of Manhattan (1926)

For over two years now, those of us who dwell in New York have been seeing in the World every day a cartoon depicting some phase of the great honeycomb which is our city. Personally, I have watched for the work of Wortman as I have watched for new "features". He has made breakfast a delight and the burdens of the day a little easier to bear. Here, it seems to me, is a man with vision and philosophy - a poet with pity and humor in his hear, who happens to express himself in terms of drawing, rather than in terms of flowing words. Loving Manhattan as I do, having lived in its maze all my life, I have been struck with the power of these pictures, their great humanity, their unerring sense of the pathos, as well as the guttersnipe humor of our big, throbbing town.

Has it every occurred to you that humor and tears are closely allied? If one laughs too much, one weeps; and conversely, if one weeps too much, one laughs. The dividing line between the two emotions is but a hair's breadth. There are peril and despair in New York; but around the next corner there may be unbridled mirth. it is this kaleidoscopic quality of what is at once the ugliest and the most beautiful city on earth which gives it the radiance and wonder we all recognize, if we have even a touch of imagination.

Wortman has the seeing eye, the feeling heart. The pain in our streets is no less real to him than their hurdy-gurdy laughter. He blends the two. He dips beneath the surface, and extracts the best and the worst of us. He reveals the pulsating town as it is, and as it always will be. Our salesgirls, our gamins, our park-bench crowds, our flappers, our rich and our poor are the materials for his robust, kindly philosophy. He is never bitter. He is always just. He takes Manhattan at its true worth, and gets it upon paper through the magic of pencil. He is not merely a "funny" man. Like all great humorists, he is also a great philosopher.

(2) Guy Pene du Bois, Denys Wortman (1953)

Denys Wortman's work should be treated as seriously in America as that of men like Daumier and Forain in France, Hogarth and Rowlandson in England. Mr. Wortman may have more good humor than some of the caricaturists just mentioned, especially in his Mopey Dick and the Duke series, but he continues to compete with them in the study of character and in the interpretation of a certain type's inevitable impulses and movements. His collection of comments on the human comedy have, which is curiously rare in a cartoonist of today, a direct relation to life as it is lived in certain definite communities and to the lines drawn in faces by the community's mores as well as the turn of the clothes dictated by the district's fashion.

Denys Wortman claims that the Duke is himself and Mopey Dick a distortion done from the same model, that both are drawn from a large mirror before which he poses with cheeks drawn in one instance probably and certainly puffed out in the other and that their philosophy is, as far as it goes, his. There is no reason to deny or even suspect this claim except that one can easily realize that his philosophy or mode of living is more remunerative than theirs.

(3) Denys Wortman, Denys Wortman Website (2000)

Mr. Wortman lived and worked from his home on Martha's Vineyard from 1941 until his death in 1958. I'm his son, the eighth in a line of Denys Wortmans, and for some of you a familiar face on the Vineyard and current owner of the home in which many of these cartoons were created. This is my attempt to share the collective works, wit, and insight of my father. In viewing his cartoons, one will find a striking resemblance to the plight of today's realities, reminding us all of the timeless humor of social and cultural mores.

This site is dedicated with profound admiration to my father, Denys Wortman, and my mother, Hilda Renbold Wortman, who was also my father's primary idea person. She would sit on park benches and listen to the conversations around her, reporting back to my father the phrases and conversations that she overheard. From these and other captions, he would create the image, the atmosphere and the surrounding that would communicate the idea visually.