James Watt and Steam Power

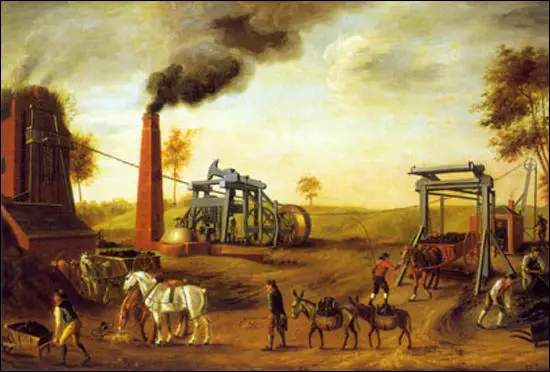

One of the major problems of mining for coal, iron, lead and tin in the 17th and 18th centuries was flooding. Miners used several different methods to solve this problem. These included pumps worked by windmills and teams of men and animals carrying endless buckets of water. (1)

Denis Papin, a French mathematician, invented the steam digester, a type of pressure cooker with a safety valve. Thomas Savery, a military engineer, used Papin's idea of using a cylinder and a piston to design a pumping engine which incorporated two different ways of utilizing steam to generate power. Steam was pumped into a cylinder and then cooled so that a vacuum was formed and atmospheric pressure drew water up. (2)

On 25th July 1698 Savery obtained a patent for fourteen years. The patent contained no description of the machine, but in June 1699 it was shown to members of the Royal Society. Savery established a workshop at Salisbury Court, London. At this workshop, mine and colliery owners could see the engine demonstrated before purchase. However, the engine could not raise water from very deep mines. Another disadvantage was its tendency to cause explosions. (3)

Thomas Newcomen

Thomas Newcomen, with his partner, John Calley, he made equipment for the mines of Devon and Cornwall which produced tin and copper. They also worked on developing a machine to pump water out of the mines. They eventually came up with the idea of a machine that would rely on atmospheric air pressure to work the pumps, a system which would be safe, if rather slow. The "steam entered a cylinder and raised a piston; a jet of water cooled the cylinder, and the steam condensed, causing the piston to fall, and thereby lift water." (4)

As Jenny Uglow has pointed out: "Newcomen's engines exploited basic atmospheric pressure, building on the way had been found to rush into a vacuum. A vacuum could be created by sucking air out of a closed vessel with a pump, but it could also be created by using steam." (5)

John Theophilus Desaguliers was someone who took a close interest in the development of this machine. "About the year 1710 Thomas Newcomen, Ironmonger and John Calley, glazier, of Dartmouth… anabaptists, made then several experiments in private, and having brought (their engine) to work with a piston... In the latter end of the year 1711 made proposals to draw the water at Griff, in Warwickshire; but their invention meeting not with reception... after a great many laborious attempts, they did make the engine work; but not being either philosophers to understand the reason, or mathematicians enough to calculate the powers and to proportion the parts, very luckily by accident found what they sought for." (6)

The engine was set up next to the mine it was draining. It had a large, rocking overhead beam. From one end hung a chain which was attached to the top of a piston encased in a cylinder. According to Gavin Weightman, the author of The Industrial Revolutionaries (2007), Newcomen and Calley had "devised and brought to efficient working order was the first really reliable steam engine in the world". (7)

Following the undoubted success of this engine a number of others were built in which Newcomen himself was involved. They included collieries at Griff, Warwickshire (1711); Bilston, Staffordshire (1714); Hawarden, Flintshire (1715); Austhorpe, West Yorkshire (1715) and Whitehaven, Cumberland (1715). During 1715 Newcomen's partner, John Calley became ill and died. (8)

In 1716 Newcomen was granted a patent for his steam-driven pumping engine. The London Gazette reported: "Whereas the invention for raising water by the impellant force of fire, authorized by Parliament, is lately brought to the greatest perfection, and all sorts of mines, etc., may be thereby drained and water raised to any height with more ease and less charge than by the other methods hitherto used, as is sufficiently demonstrated by diverse engines of this invention now at work in the several counties of Stafford, Warwick, Cornwall, and Flint. These are therefore, to give notice that if any person shall be desirous to treat with the proprietors for such engines, attendance will be given for that purpose every Wednesday at the Sword Blade Coffee House in Birchin Lane, London." (9)

Over the next few years over 100 of these machines were purchased. This included several machines sold overseas. He continued to improve the machine. In early models the steam in the cylinder was cooled by running cold water over the outside. Later it was discovered that an injection of cold water into the cylinder was much more effective. (10) He continued to work on developing other machines. In 1725 he wrote to the Lord Chief Justice Robert Raymond about "a new invented wind engine". (11)

It seems that Newcomen was well-respected by fellow businessmen who seemed very pleased with the performance of his machine. In 1719 James Lowther wrote to John Spedding: "There is nothing that will do our business so well and be less liable to accidents than the engine, and… it s the cheapest, safest and best way of keeping the colliery dry." (12) In another letter Lowther wrote: "Mr. Newcomen is a perfect honest man and had helped to make this matter easy, he owns none of the rest that had Fire Engines have been so fair with them as we have." (13)

James Watt

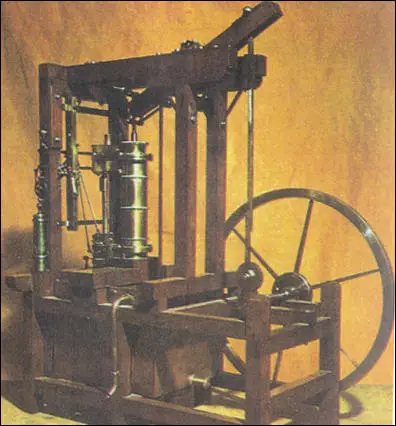

In 1763 James Watt was sent a steam engine produced by Thomas Newcomen to repair. Although many mine-owners used Newcomen's steam-engines, they constantly complained about the cost of using them. The main problem with it was they used a great deal of coal and were therefore expensive to run. While putting it back into working order, Watt attempted to discover how he could make the engine more efficient. (14)

Watt later told his friend, the Glasgow engineer, Robert Hart: "I had gone to take a walk on a fine Sabbath afternoon. I passed the old washing-house. I was thinking upon the engine at the time and had gone as far as the Herd's house when the idea came into my mind, that as steam was an elastic body it would rush into a vacuum, and if a communication was made between the cylinder and an exhausted vessel, it would rush into it, and might be there condensed without cooling the cylinder." (15)

Watt worked on the idea for several months and eventually produced a steam engine that cooled the used steam in a condenser separate from the main cylinder. Watt calculated that this would produce a saving of fuel of around 75 per cent. It has been argued by Jennifer Tann that "Watt identified several problems, of which the wastage of steam during the ascent of the engine piston and the method of vacuum formation in which the system was cooled were two of the most fundamental. He therefore made a new model, slightly larger than the original, and conducted many experiments on it.... The theory of latent heat underpinned Watt's experiments on the separate condenser, in which the steam cylinder remained hot while a separate condensing vessel was cold." (16)

In April, 1765, James Watt wrote to James Lind about his invention. "I have now almost a certainty of the facturum of the fire-engine, having determined the following particulars: the quantity of steam produced; the ultimatum of the lever engine; the quantity of steam produced; the quantity of steam destroyed by the cold of its cylinder; the quantity destroyed in mine... mine ought to raise water to 44 feet with the same quantity of steam that there does to 32 (supposing my cylinder as thick as theirs). I can now make a cylinder of 2 feet diameter and 3 feet high only a 40th of an inch thick, and strong enough to resist the atmosphere... in short, I can think of nothing else but this machine." (17)

James Watt built an instrument-maker's model but the next stage involved producing a massive working engine made of brick and iron. Watt had no money for large-scale models and so he had to seek a partner with capital. Watt's friend, Joseph Black, introduced him to John Roebuck, the owner of Carron Ironworks near Falkirk in Scotland. He also owned nearby coal mines to provide fuel for his ironworks. (18)

Roebuck agreed and the two men went into partnership. Roebuck held two-thirds of the original patent (9th January 1769) in return for discharging some of Watt's debts. James Patrick Muirhead, the author of The Life of James Watt (1854) claims that Roebuck's made every effort to get Watt's machine into production as he was "ardent and sanguine in the pursuit of his undertakings". (19)

James Watt and Matthew Boulton

In March 1773 Roebuck became bankrupt. At the time he owed Matthew Boulton over £1,200. Boulton knew about Watt's research and wrote to him making an offer for Roebuck's share in the steam-engine. Roebuck refused but on 17th May, he changed his mind and accepted Boulton's terms. James Watt was also owed money by Roebuck, but as he had done a deal with his friend, he wrote a formal discharge "because I think the thousand pounds he (Boulton) he has paid more than the value of the property of the two thirds of the inventions." (20)

Boulton pointed out that before he would give Watt financial backing, he insisted that the 1769 patent, with only eight years to run, should be extended to twenty-five years. This meant petitioning the House of Commons. By 1775 the two men had their patent which gave them "the sole use and property of certain steam-engines of his invention, throughout the majesty's dominions." This prevented others from making steam-engines which contained improvements of their own. (21)

Under the terms of the partnership Watt assigned two-thirds of both property and the patent to Boulton. In return Boulton undertook to pay the expenses already incurred, to meet the costs of experiments, and to pay for materials and wages. The profits were to be divided in proportion to their shares. "It would be incorrect to stereotype Boulton as the entrepreneur and Watt as the inventor, for Boulton made many suggestions for improvements to the engine and Watt also had a good head for business. But there is no doubt that Boulton's flair for marketing was significant for the early success of the business." (22)

For the next eleven years Boulton's factory producing and selling Watt's steam-engines. These machines were mainly sold to colliery owners who used them to pump water from their mines. Watt's machine was very popular because it was four times more powerful than those that had been based on the Thomas Newcomen design.

Rotary-Motion Steam Engine

James Watt continued to experiment and in 1781 he produced a rotary-motion steam engine. Whereas his earlier machine, with its up-and-down pumping action, was ideal for draining mines, this new steam engine could be used to drive many different types of machinery. Richard Arkwright was quick to importance of this new invention, and in 1783 he began using Watt's steam-engine in his textile factories. (23)

The ironmaster John Wilkinson, was one of the first people to buy Watt's steam engine. He installed eleven engines at his Bradley ironworks by the 1790s and at least seven elsewhere. The partners depended heavily on Wilkinson for it was he who was capable of boring engine cylinders with greater accuracy than any other iron-founder. (24)

Eric Hobsbawm has argued that James Watt's steam engine was "the foundation of industrial technology". (25) Arthur Young commented in his book, Tours in England and Wales (1791) about the impact that Watt had on Britain: "What trains of thought, what a spirit of exertion, what a mass and power of effort have sprung in every path of life, from the works of such men as Brindley, Watt, Priestley, Harrison, Arkwright.... In what path of life can a man be found that will not animate his pursuit from seeing the steam-engine of Watt?" (26)

Richard Guest pointed out that Watt's steam engine that drove the power looms was extremely popular with factory owners: "The increasing number of steam-looms is a certain proof of their superiority over the hand-looms. In 1818, there were in Manchester, Stockport, Middleton, Hyde, Stayley Bridge, and their vicinities, 14 factories, containing about 2,000 looms. In 1821, there were in the same neighbourhoods 32 factories, containing 5,732 looms. Since 1821, their number has still increased, and there are at present not less than 10,000 steam-looms at work in Great Britain." (27)

Boulton & Watt company had a virtual monopoly over the production of steam-engines. Watt charged his customers a premium for using his steam engines. To justify this he compared his machine to a horse. Watt calculated that a horse exerted a pull of 180 lb., therefore, when he made a machine, he described its power in relation to a horse, i.e. "a 20 horse-power engine". Watt worked out how much each company saved by using his machine rather than a team of horses. The company then had to pay him one third of this figure every year, for the next twenty-five years. (28)

Henry Brougham later recalled: "There was one quality, which most honourably distinguished him from too many inventors, and was worthy of all imitation, he was not only entirely free from jealously, but he exercised a careful and scrupulous self-denial, and was anxious not to appear, even by accident, as appropriating to himself that which he thought belonged to others." (29)

Lunar Society

James Watt became an important member of the Lunar Society of Birmingham. The group took this name because they used to meet to dine and converse on the night of the full moon. The group first began meeting as a group in 1768. Other members included Matthew Boulton, Erasmus Darwin, Josiah Wedgwood, Joseph Priestley, James Brindley, Thomas Day, William Small, John Whitehurst, John Robison, Joseph Black, William Withering, John Wilkinson, Richard Lovell Edgeworth, Joseph Wright and Erasmus Darwin.

The historian, Jenny Uglow, has argued: "It has been said that the Lunar Society kick-started the industrial revolution. No individual or group can be said to change a society in such a way, and time and again one can see that if they hadn't invented or discovered something, someone else would have done it. Yet this small group of friends really was at the leading edge of almost every movement of its time in science, in industry and in the arts, even in agriculture. They were pioneers of the turnpikes and canals and of the new factory system. They were the group who brought efficient steam power to the nation." (30)

Watt deeply felt the loss of some of his friends from the Lunar Society. A number of Watt's friends died at the turn of the century. Josiah Wedgwood (1795), Joseph Black (1799), Erasmus Darwin (1802), Joseph Priestley (1804) and John Robison (1805). It is claimed that in retirement he was haunted by the fear that his mental faculties were failing. (31)

Watt's partner, Matthew Boulton, suffered from stones in the kidneys, and he told a friend: "My doctors say my only chance of continuing in this world depends on my living quiet in it." (32) He died aged 81 of kidney failure on 17th August 1809. Watt wrote that Boulton was "not only an ingenious mechanic, well skilled in all the practices of the Birmingham manufacturers, but possessed in a high degree the faculty of rendering any new invention of his own or others useful to the public, by organising and arranging the processes by which it could be carried on." (33)

James Watt died aged 73 at Heathfield in Handsworth, Birmingham, on 25th August 1819 and was buried beside Matthew Boulton in St Mary's Church on 2nd September 1819. He left over £60,000 (£81,000,000 in today's money) in his will to his family. (34)