Public Health Reforms in the 19th Century

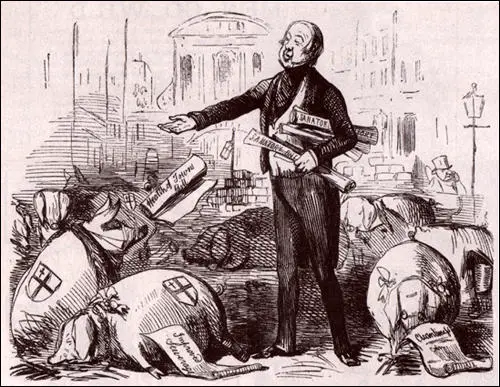

The government decided to order a full-scale enquiry into the health of British people. The person put in charge of this enquiry was Edwin Chadwick. His report, The Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population, was published in 1842. Chadwick argued that slum housing, inefficient sewerage and impure water supplies in industrial towns were causing the unnecessary deaths of about 60,000 people every year: "Of the 43,000 cases of widowhood, and 112,000 cases of orphanage relieved from the poor rates in England and Wales, it appears that the greatest proportion of the deaths of heads of families occurred from... removable causes... The expense of public drainage, of supplies of water laid on in houses, and the removal of all refuse... would be a financial gain.. as it would reduce the cast of sickness and premature death." (1)

Chadwick was a disciple of Jeremy Bentham who questioned the value of all institutions and customs by the test of whether they contributed to the "greatest happiness of the greatest number". (2) Chadwick claimed that middle-class people lived longer and healthier lives because they could afford to pay to have their sewage removed and to have fresh water piped into their homes. For example, he showed the average age of death for the professional class in Liverpool was 35, whereas it was only 15 for the working-classes. (3)

Edwin Chadwick

Chadwick criticised the private companies that removed sewage and supplied fresh water, arguing that these services should be supplied by public organisations. He pointed out that private companies were only willing to supply these services to those people who could afford them, whereas public organisations could make sure everybody received these services. He argued that the "cost of removing sewage would be reduced to a fraction by carrying it away by suspension in water". The government therefore needed to provide a "supply of piped water, and an entirely new system of sewers, using circular, glazed clay pipes of relatively small bore instead of the old, square, brick tunnels". (4)

However, there were some influential and powerful people who were opposed to Edwin Chadwick's ideas. These included the owners of private companies who in the past had made very large profits from supplying fresh water to middle-class districts in Britain's towns and cities. Opposition also came from prosperous householders who were already paying for these services and were worried that Chadwick's proposals would mean them paying higher taxes. The historian, A. L. Morton, claims that his proposed reforms made him "the most detested man in England." (5)

When the government refused to take action, Chadwick set up his own company to provide sewage disposal and fresh water to the people of Britain. He planned to introduce the "arterial-venous system". The system involved one pipe taking the sewage from the towns to the countryside where it would be sold to farmers as manure. At the same time, another pipe would take fresh water from the countryside to the large populations living in the towns.

Chadwick calculated that it would be possible for people to have their sewage taken away and receive clean piped water for less than 2d. a week. However, Chadwick launched the Towns Improvement Company during the railway boom. Most people preferred to invest their money in railway companies. Without the necessary start-up capital, Chadwick was forced to abandon his plan. (6)

Nottingham became one of the first towns in Britain to pipe fresh water into all homes. Thomas Hawksley was appointed as chief engineer and in 1844 he was interviewed by a Parliamentary Committee about his work: "Before the supply was laid on in the houses water was sold chiefly to the labouring-classes by carriers at the rate of one farthing a bucket; and if the water had to be carried any distance up a court a halfpenny a bucket was, in some instances, charged. In general it was sold at about three gallons for a farthing. But the Company now delivers to all the town 76,000 gallons for £1; in other words, carries into every house 79 gallons for a farthing, and delivers water night and day, at every instant of time that it is wanted, at a charge 26 times less than the old delivery by hand." (7)

1848 Public Health Act

In 1847 the British government proposed a Public Health Bill that was based on some of Edwin Chadwick's recommendations. There were still a large number of MPs who were strong supporters of what was known as laissez-faire. This was a belief that government should not interfere in the free market. They argued that it was up to individuals to decide on what goods or services they wanted to buy. These included spending on such things as sewage removal and water supplies. George Hudson, the Conservative Party MP, stated in the House of Commons: "The people want to be left to manage their own affairs; they do not want Parliament... interfering in everybody's business." (8)

Supporters of Chadwick argued that many people were not well-informed enough to make good decisions on these matters. Other MPs pointed out that many people could not afford the cost of these services and therefore needed the help of the government. The Health of Towns Association, an organisation formed by doctors, began a propaganda campaign in favour of reform and encouraged people to sign a petition in favour of the Public Health Bill. In June 1847, the association sent Parliament a petition that contained over 32,000 signatures. However, this was not enough to persuade Parliament, and in July the bill was defeated. (9)

A few weeks later news reached Britain of an outbreak of cholera in Egypt. The disease gradually spread west, and by early 1848 it had arrived in Europe. The previous outbreak of cholera in Britain in 1831, had resulted in the deaths of over 16,000 people. In his report, published in 1842, Edwin Chadwick had pointed out that nearly all these deaths had occurred in those areas with impure water supplies and inefficient sewage removal systems. Faced with the possibility of a cholera epidemic, the government decided to try again. This new bill involved the setting up of a Board of Health Act, that had the power to advise and assist towns which wanted to improve public sanitation. (10)

In an attempt to persuade the supporters of laissez-faire to agree to a Public Health Act, the government made several changes to the bill introduced in 1847. For example, local boards of health could only be established when more than one-tenth of the ratepayers agreed to it or if the death-rate was higher than 23 per 1000. Chadwick was disappointed by the changes that had taken place, but he agreed to become one of the three members of the central Board of Health when the act was passed in the summer of 1848. However, the act was passed too late to stop the outbreak of cholera that arrived in Britain that September. In the next few months, cholera killed 80,000 people. Once again, it was mainly the people living in the industrial slums who caught the disease. (11)

By 1853 over 160 towns and cities had set up local boards of health. Some of these boards did extremely good work and were able to introduce important reforms. Thomas Hawksley, for example, after his success in Nottingham, was appointed to many major water supply projects across England, including schemes for Liverpool, Sheffield, Leicester, Leeds, Derby, Oxford, Cambridge, Sunderland, Lincoln, Darlington, Wakefield and Northampton. (12)

In other towns, supporters of laissez-faire were able to prevent action being taken. Most MPs remained unhappy about government involvement in the free market. As Michael Flinn, the author of Public Health Reform in Britain (1968) pointed out "the opponents of sanitary reform, who wanted to have an end to all state interference in this field, led to the final disbandment of the Board in 1858. (13)

The Great Stink

During the summer of 1858 there was a steady accumulation of sewage locked in the tidal reach of the river. At the same time it was a very hot summer and took place during a debate on the future of London's sewers. "During the discussion and disputes that were taking place on the main drainage system the state of the Thames was becoming daily much worse, and was exciting great alarm and indignation. The subject was repeatedly noticed in Parliament, and strong language was used in both Houses." (14)

One MP said that it was a notorious fact that it became impossible to stay in the committee rooms and the library were "utterly unable to remain there in consequence of the stench which arose from the river." Another commented that "by a perverse ingenuity one of the noblest of rivers had been changed into a cesspool". Lawrence Palk described the Thames as "one vast sewer, which would surely spread disease and death around." (15)

The House of Lords also debated what became known as the "Great Stink". Earl Charles Grey said it was impossible that "such a stench should not be exceedingly dangerous". Charles Yorke, 5th Earl of Hardwicke, claimed that the "made the main sewer for the whole of London, and had been converted into a most abominable ditch... the gaseous matter flowed along the river, and at high water the state of the atmosphere was worse than at any other time of the tide." (16)

Parliament reacted by giving permission for Joseph Bazelgette to build a new sewer network for London. This involved a series of "intercepting" sewers running west to east to receive the discharge of the existing arterial north-south sewers, thus intercepting the sewage before its discharge into the Thames. After much research the main outfalls points were sited at Barking and Crossness. (17)

In 1865-66 there was another cholera epidemic which resulted in the deaths of 20,000 people. The government responded by setting up another enquiry into public health. As a result of this report, further reforms were introduced. In 1871 a new government department was formed to look after public health. The following year, a law was passed that divided the country into Sanitary Authorities. Each authority had to appoint a sanitary inspector and a medical officer of health who had the responsibility of improving the region's public health. These measures were confirmed in the 1875 Public Health Act. (18)

Primary Sources

(1) R. A. Lewis, Edwin Chadwick and Public Health (1952)

Few men have done so much for their fellow-countrymen as Edwin Chadwick, and received in return so little thanks... Chadwick's reputation suffers from... a hatred of the man and his work, widespread in his, day, and colouring even now the impressions of him formed by a later generation.

(2) Thomas Hawksley, interviewed by a Parliamentary Committee (15th February, 1844)

Q: What is the number of houses to which water is supplied from the works which you superintend at Nottingham?A: About 8,000, containing a population of about 35,000 persons. We find that one experienced man, and one boy of 18 years of age are, on the system of constant supply, quite sufficient to manage the distribution of the supply to about 8,000 tenements, and keep all the works of distribution in perfect repair...

Q: Now, do you find that tenants are apt, for the sake of the lead pipes, to cut off their own supplies of water; and what, under all circumstances, is your experience on the point?

A: We have some of the poorest and worst conditioned people in Nottingham, and we scarcely ever experience anything of the kind. In fact, the water at high pressure serves as a police on the pipe. The cutting off a cock with the water at high pressure is rather a difficult matter to do quietly: "knocking up" is too noisy; and when a knife is put into such a pipe, and a slit is made, a sharp, flat, wide stream issues, very inconvenient to the operator; and when the pipe is divided there is the full rush of the jet to denounce the thief. We have lead-pipes all over the town, in the most exposed places, and I can affirm that such an event rarely occurs out of the houses, and never within.

Q: What has been the effect produced on their habits by the introduction of water into the houses of the labouring classes?

A: At Nottingham the increase of personal cleanliness was at first very marked indeed; it was obvious in the streets. The medical men reported that the increase of cleanliness was very great in the houses, and that there was less disease.

Q: When, on the return home of the labourers' family, old or young, tired perhaps with the day's labour, the water has to be fetched from a distance out of doors in cold or in wet, in frost or in snow, is it not well known to those acquainted with the labourers' habit that the use of clean water, and the advantages of washing and cleanliness, will be foregone to avoid the annoyance of having to fetch the water?

A: Yes, that is a general and notorious fact. When the distance to be traversed is comparatively trifling, it still operates against the free use of water.

Q: Before the water was laid on in the houses of Nottingham, were the labouring classes accustomed to purchase water?

A: Before the supply was laid on in the houses water was sold chiefly to the labouring-classes by carriers at the rate of one farthing a bucket; and if the water had to be carried any distance up a court a halfpenny a bucket was, in some instances, charged. In general it was sold at about three gallons for a farthing. But the Company now delivers to all the town 76,000 gallons for £1; in other words, carries into every house 79 gallons for a farthing, and delivers water night and day, at every instant of time that it is wanted, at a charge 26 times less than the old delivery by hand.

Q: Under what circumstances do you consider the utility of the supply of water to be influenced by the defective state of the drainage?

A: Where one system terminated the other must commence. The use of water, however liberally supplied, will be limited and restricted by any inconvenience attending its removal. Its use as a means of cleansing and removing refuse, by the application of the water closet principle, will be directly dependent on the state of the drains...

My own observation and enquiry convince me that the character and habits of a working family are more depressed and deteriorated by the defects of their habitations than by the greatest pecuniary privations to which they are subject. The most cleanly and orderly female will invariably despond and relax her exertions under the influence of filth, damp and stench and at length ceasing to make further effort, probably sink into a dirty, noisy, discontented and perhaps gin-drinking drab - the wife of a man who has no comfort in his house, the parent of children whose home is the street or the gaol. The moral and physical improvements certain to result from the introduction of water and water-closets into the houses of the working classes are far beyond the pecuniary advantages (referring to the customary sale of night-soil. It was estimated that each tenement produced two good car-loads per annum), however considerable these may under circumstances appear.

(3) George Hudson, speech in the House of Commons (3rd July 1847)

I admit that there was a very general feeling in Yorkshire in favour of the adoption of some sanitary regulations, and that petitions praying the House to consider and sanction such measures had been presented from corporations and from public meetings.... I think that the evils resulting from defective sanitary regulations had been very much exaggerated, and I hope the House would pause before they gave their assent to this measure... The country is sick of centralisation of commissions of inquiries. The people want to be left to manage their own affairs; they do not want Parliament to be so paternal as it wishes to be - interfering in everybody's business.

(4) Robert Rawlinson, a Board of Health Inspector, letter to Edwin Chadwick (30th September 1852)

On my arrival in Hexham, I found the town in a state of ferment as to the inquiry, the bellman was perambulating the streets summonsing the ratepayers to a meeting to oppose the inquiry. This was repeated during the evening, one of the meetings being for the evening, the other for the morning. Several of the promoters called in upon me during the evening, evidently fearing the morning's meeting. I explained the Act to them, as the most absurd statements had been published and were believed. I learned that the leader of the opponents was a Local Solicitor. The promoters were most anxious to learn what course I should take, as they feared to come forward and support the measure in public. That is they would attend the meeting but wished to avoid taking an active part in the proceedings. I told them this was exactly the course I desired they should take - namely - let the opposition have all the talking to themselves, and so leave them to me as I was quite sure out of their own evidence I could convict, if not convince them.

The inquiry had to be adjourned to a large room as there was a full and rather formidable attendance. The day being wet many workmen were there. I commenced the inquiry by a short statement of the proceedings which had brought me down - and then glanced rapidly over the powers contained in the Act - taking up one by one the objections which I had been informed the promoters of the opposition had made. I then requested any persons having evidence to offer either for or against to come forward and tender it. the opponents entered most resolutely into the arena, declaring that Hexham was well supplied with water; and was, in all other respects, a perfect town. I inquired for the return of the mortality, and found that, for the last seven years, it was actually some 29.5 in the thousand, but with "cooked" returns it was 24.5 in the thousand. I then called the Medical Officers and the Relieving Officers and soon got amongst causes of fever, small-pox, and excessive money relief. I then traced disease to crowded room tenements, undrained streets, lanes, courts and crowded yards, foul middens, privies, and cesspools. The water I found was deficient in quantity and most objectionable in quality, dead dogs having to be lifted out of the reservoir. And though the opposition fought stoutly they were obliged publicly to acknowledge that improvement was needed - they, however, dreaded the General Board, and the Expense. I then explained the constitution of the Board and stated that their powers would be used to instruct, protect, and to check extravagant expenditure. By this time the eagerness of the opponents had somewhat subsided, the body of the meeting had come partially round, and so I entered into an examination of the promoters who came willingly forward. At the termination of the inquiry several of the opponents came forward and stated that I had removed their objections and they wished the Act could be applied immediately.

Today I have inspected the town - and have found it as bad as any place I ever saw. I have had at least twenty gentlemen with me all day although it has rained most of the time. The town is old, and in as bad a condition as Whitehaven, and I don't know that I can say anything worse of it. I am staying at the best Hotel in the town, but there is no watercloset, only a filthy privy at some distance, the way to it being past the kitchen. I have just been out in the dark and rain blundering and found some one in the place.

I have inspected the sources of the present water supply, and find that the water is taken from an open brook, filthy and muddy in wet weather, and filthy and bright in dry weather. In the same districts I have found; or rather, been shewn, springs - pure and soft - and at a sufficient elevation to give 150 foot pressure in the town - and in abundance for the whole population. The existing springs will be added to if requisite by deep drainage. Most complete water works might be formed at a cheap cost. And the town may be sewered and drained for nothing, as a Nursery Man adjoining has stated that he will give £100 a year for the refuse, if it is all collected by drains. There are many acres of market gardens and nursery grounds within reach of the outlet sewer and more than £100 a year will be obtained.

Since the inspection today I have had parties from both sides with me, the opponents trying to explain away their opposition; the promoters to furnish information; and, at times, I have had nine or ten gentlemen at once, belonging to both parties. The leader of the opposition has made me a present of some Anglo-Saxon coins - called Stycus, which were found in Hexham Church Yard.

(5) Edwin Chadwick, The Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population (1842)

Here, then, we have from the one agent, a dose and polluted atmosphere, two different sets of effects; the one set here noticed engendering improvidence, expense, and waste, - the other, the depressing effects of external and internal miasma on the nervous system, tending to incite the habitual use of ardent spirits; both tending to precipitate this population into disease and misery.

The familiarity with the sickness and death constantly present in the crowded and unwholesome districts, appears to re-act as another concurrent cause in aggravation of the wretchedness and vice in which they are plunged. Seeing the apparent uncertainty of the morrow, the inhabitants really take no heed of it, and abandon themselves with the recklessness and avidity of common soldiers in a war to whatever gross enjoyment comes within their reach. All the districts I visited, where the rate of sickness and mortality was high, presented, as might be expected, a proportionate amount of severe cases of destitute orphanage and widowhood; and the same places were marked by excessive recklessness of the labouring population.

In Dumfries, for example, it is estimated, that the cholera, swept away one-eleventh part of the population. Until recently, the town had not recovered from the severe effects of the visitation, and the condition of the orphans was most deplorable. Amongst young artisans who were earning from 16s. to 18s. a week, I was informed that there were very few who made any reserves against the casualties of sickness. I was led to ask the provost what number of bakers' shops there were? "Twelve", was his answer. And what number of whiskey-shops may the town possess? "Seventy-nine" was the reply. If we might rely on the inquiries made of working-men when Dr Arnott and I went through the wyndsl of Edinburgh, their consumption of spirits bore almost the like proportion to the consumption of wholesome food. We observed to Captain Stuart, the superintendent of the police at Edinburgh, in our inspection of the wynds, that life appeared to be of little value, and was likely to be held cheap in such spots. He stated, in answer, that a short time ago a man had been executed for the murder of his wife in a fit of passion in the very room we had accidentally entered, and where we were led to make the observation. At a short distance from that spot, and amidst others of this class of habitation, were those which had been the scenes of the murders by Burke and Hare. Yet amidst these were the residences of working men engaged in regular industry. The indiscriminate mixture of workpeople and their children in the immediate vicinity, and often in the same rooms with persons whose character was denoted by the question and answer more than once exchanged, "When were you last washed?" "When I was last in prison", was only one mark of the entire degradation to which they had been brought. The working-classes living in these districts were equally marked by the abandonment of every civil or social regulation. Asking some children in one of the rooms of the wynds in which they swarmed in Glasgow what were their names, they hesitated to answer, when one of the inmates said, they called them, mentioning some nicknames. "The fact is," observed Captain Miller, the superintendent of the police, "they really have no names. Within this range of buildings I have no doubt I should be able to find a thousand children who have no names whatever, or only nicknames, like dogs." There were found amidst the occupants, labourers earning wages undoubtedly sufficient to have paid for comfortable tenements, men and women who were intelligent and so far as could be ascertained, had received the ordinary education which should have given better tastes and led to better habits. My own observations have been confirmed by the statement of Mr Sheriff Alison, of Glasgow, that in the great manufacturing towns of Scotland, `in the contest with whiskey, in their crowded population, education has been entirely overthrown'. The ministers, it will be seen, make similar reports from the rural districts. On the observation of other districts, and the comparison of the habits of the same workmen in town and country, it will be seen that I consider that the use of the whiskey and the prostration of the education and moral habits for which the Scottish labourers have been distinguished is, to a considerable extent, attributable to the surrounding physical circumstances, including the effects of bad ventilation. The labourers presented to our notice in the condition described, in the crowded districts, were almost all Scotch. It is common to ascribe the extreme of misery and vice wholly to the Irish portion of the population of the towns in Scotland. A short inspection on the spot would correct this error. Mr Baird, in his report on the sanitary condition of the poor of Glasgow, observes that "the bad name of the poor Irish had been too long attached to them". Dr Cowan, of Glasgow, stated that "From ample opportunities of observation, they appeared to him to exhibit much less of that squalid misery and addiction to the use of ardent spirits than the Scotch of the same grade". Instances were indeed stated to us, where the Irish were preferred for employment from their superior steadiness and docility; and Mr Stuart, the Factory Inspector for Scotland, states that " instances are now occurring of a preference being given to them as workers in the flax factories on account of their regular habits, and that very significant hints have been given by extensive factory owners, that Irish workmen will be selected unless the natives of the place, and other persons employed by them, relinquish the prevailing habits of intemperance". Dr Scott Alison, in his report on Tranent, has described the population in receipt of high wages, but living under similar influences, as prone to passionate excitement, and as apt instruments for political discontents; their moral perceptions appeared to have been obliterated, and they might be said to be characterised by a "ferocious indocility which makes them prompt to wrong and violence, destroys their social nature, and transforms them into something little better than wild beasts".

It is to be regretted that the coincidence of pestilence and moral disorder is not confined to one part of the island, nor to any one race of the population. The over-crowding and the removal of what may be termed the architectural barriers or protections of decency and propriety, and the causes of physical deterioration in connexion with the moral deterioration, are also fearfully manifest in the districts in England, which, at the time to which the evidence refers, were in a state of prosperity.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)