Jean Hill

Jean Hill was born in 1931. She worked as a teacher in Oklahoma City before moving to a Dallas school in 1962. On 22nd November, 1963, Hill, watched the motorcade of President John F. Kennedy from the grassy knoll facing the Texas School Depository Building. Hill and her friend, Mary Moorman, who was taking Polaroid pictures of the motorcade, were only a few feet away from President John F. Kennedy when he was shot. Hill and Moorman thought the shots had come from behind her on the grassy knoll and as soon as the firing stopped they ran towards the wooden fence in an attempt to find the gunman. Hill claims that they were detained by two secret service men. After searching the two women they confiscated the picture of the assassination.

Hill gave a statement to the police where she stated: "Mary Moorman started to take a picture. We were looking at the president and Jackie in the back seat... Just as the president looked up two shots rang out and I saw the president grab his chest and fell forward across Jackie's lap... There was an instant pause between two shots and the motorcade seemingly halted for an instant. Three or four more shots rang out and the motorcade sped away."

Shirley Martin telephoned Hill on 25th January, 1964. She told Martin that as soon as the firing stopped they ran towards the wooden fence in an attempt to find the gunman. However, they were detained by two secret service men. After searching the two women they confiscated the picture of the assassination. Hill told Martin that she was very scared as another witness, Warren Reynolds, had been shot in the head by an unknown assailant, the night before: "Mrs Hill told me that she and Miss Moorman had received many threatening phone calls urging them to keep quiet and when they reported these to the Dallas police, they received an official brush-off. Mrs. Hill said Miss Moorman would not talk to me as she was much more frightened and upset over the whole thing than Mrs. Hill was."

Hill later gave evidence to the Warren Commission that was highly controversial. She claimed that she heard between four and six shots. Hill was also convinced that some of the shots came the grassy knoll. In interviews on television after the assassination Hill said she saw "a little white dog" in the rear seat of the president's car. As there was no dog in the car, the reliability of Hill's witness statement was undermined. However, 25 years later, it was revealed that a small white stuffed animal was on the back seat of the car. A child had presented it to Jackie Kennedy at the beginning of the tour of Dallas. This information was suppressed in order to discredit Hill as a reliable witness.

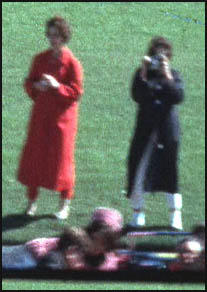

and Mary Moorman when John F. Kennedy was shot.

Jean Hill told Mark Lane: "The FBI was here for days. They practically lived here. They just didn't like what I told them I saw and heard when the President was assassinated. She declined to permit a filmed interview, stating, for two years I have told the truth, but I have two children to support and I am a public school teacher. My principal said it would be best not to talk about the assassination, and I just can't go through it all again. I can't believe the Warren Report. I know it's all a lie, because I was there when it happened, but I can't talk about it anymore because I don't want the FBI here constantly and I want to continue to teach here. I hope you don't think I'm a coward, but I cannot talk about the case anymore."

For many years Hill refused to give interviews about the John Kennedy assassination. However, in 1990, Hill agreed to work as a technical adviser on Oliver Stone's motion picture, JFK. The following year she revealed what happened after the assassination: "They (Secret Service agents) took me to the Records Building and we went up to a room on the fourth floor. There were two guys sitting there on the other side of a table looking out a window that overlooked the killing zone, where you could see all of the goings on. You got the impression that they had been sitting there for a long time. They asked me what I had seen, and it became clear that they knew what I had seen. They asked me how many shots I had heard and I told them four to six. And they said, No, you didn't. There were three shots. We have three bullets and that's all we're going to commit to now. I said, Well, I know what I heard, and they told me, What you heard were echoes. You would be very wise to keep your mouth shut. Well, I guess I've never been that wise. I know the difference between firecrackers, echoes, and gunshots. I'm the daughter of a game ranger, and my father took me shooting all my life." In 1992 Hill published her book on the case, JFK: The Last Dissenting Witness.

Jean Hill, who worked as a schoolteacher in Dallas for over twenty years, died on 7th November, 2000.

Primary Sources

(1) Jean Hill, statement made to the Dallas Police Department (22nd November, 1963)

Mary Moorman started to take a picture. We were looking at the president and Jackie in the back seat... Just as the president looked up two shots rang out and I saw the president grab his chest and fell forward across Jackie's lap... There was an instant pause between two shots and the motorcade seemingly halted for an instant. Three or four more shots rang out and the motorcade sped away. I saw some men in plain clothes shooting back but everything was a blur and Mary was pulling on my leg saying "Get down their shooting".

(2) Jean Hill was interviewed by Arlen Specter for the Warren Commission (24th March, 1964)

Arlen Specter: Now, what had you done immediately before noontime, Mrs. Hill?

Jean Hill: We had been there for about an hour and a half and had been walking up and down and back and forth.

Arlen Specter: When you say "we" whom do you mean by that?

Jean Hill: My friend, Mary Moorman, that took the picture.

Arlen Specter: She had a camera with her?

Jean Hill: Yes; a Polaroid. We had been taking pictures all morning.

Arlen Specter: And did you have a camera with you?

Jean Hill: No.

Arlen Specter: And tell me what you observed as the President's motorcade passed by?

Jean Hill: You mean.

Arlen Specter: Start any place that you find most convenient and just tell me in your own way what happened.

Jean Hill: Well, as they came toward us, we had been taking pictures with this Polaroid camera and since it was a Polaroid we knew we had only one chance to get a picture, and at the time she had taken a picture just a few minutes before and I had grabbed it out of the camera and wrapped it and put it in my pocket. Just about that time he drew even with us. Jean Hill: The President's car. We were standing on the curb and I jumped to the edge of the street and yelled, "Hey, we want to take your picture," to him and he was looking down in the seat - he and Mrs. Kennedy and their heads were turned toward the middle of the car looking down at something in the seat, which later turned out to be the roses, and I was so afraid he was going to look the other way because there were a lot of people across the street and we were, as far as I know, we were the only people down there in that area, and just as I yelled, "Hey," to him, he started to bring his head up to look at me and just as he did the shot rang out. Mary took the picture and fell on the ground and of course there were more shots.

Arlen Specter: How many shots were there altogether?

Jean Hill: I have always said there were some four to six shots. There were three shots - one right after the other, and a distinct pause, or just a moment's pause, and then I heard more.

Arlen Specter: How long a time elapsed from the first to the third of what you described as the first three shots?

Jean Hill: They were rapidly - they were rather rapidly fired.

Arlen Specter: Could you give me an estimate on the timespan on those three shots?

Jean Hill: No; I don't think I can.

Arlen Specter: Now, how many shots followed what you described as the first three shots?

Jean Hill: I think there were at least four Or five shots and perhaps six, but I know there were more than three.

Arlen Specter: How much time elapsed from the very first shot until the very last shot, will you estimate?

Jean Hill: I don't think I could, properly, but my girl friend fell on the ground after about - during the shooting - right, I would say, just immediately after she had taken the picture - probably about the third shot. She fell on the ground and grabbed my slacks and said, "Get down, they're shooting." And, I knew they were but I was too stunned to move, so I didn't get down. I just stood there and gawked around.

(3) Jean Hill was interviewed by Arlen Specter from the Warren Commission (24th March, 1964)

Arlen Specter: Did you have any conscious impression of where the second shot came from?

Jean Hill: No.

Arlen Specter: Any conscious impression of where this third shot came from?

Jean Hill: Not any different from any of them. I thought it was just people shooting from the knoll - I did think there was more than one person shooting.

Arlen Specter: You did think there was more than one person shooting?

Jean Hill: Yes, sir.

Arlen Specter: What made you think that?

Jean Hill: The way the 'gun report sounded and the difference in the way they were fired-the timing.

Arlen Specter: What was your impression as to the source of the second group of shots which you have described as the fourth, perhaps the fifth, and perhaps the sixth shot?

Jean Hill: Well, nothing, except that I thought that they were fired by someone else.

Arlen Specter: And did you have any idea where they were coming from?

Jean Hill: No; as I said, I thought they were coming from the general direction of that knoll.

(4) Jean Hill interviewed by Arlen Specter for the Warren Commission (24th March, 1964)

Arlen Specter: Now, moving on to the question about Mark Lane, what did you tell him other than that which you have told me here today?

Jean Hill: He asked me where we were taken and I told him in the pressroom, that we didn't know it was the pressroom at the time, and that we didn't know we couldn't leave and because they kept standing across the door and the first time we really - we were getting tired of it, I mean, we had been down there quite a while and we were getting tired of it and we wanted to leave and this is what I told him, and so some man came in and offered Mary a sum, I think - say - $10,000 or something like this for this picture.

We realized that - they said, "Don't sell the picture." He was a representative of either Post or Life, and they said, "Don't sell that picture until our representatives have contacted you or a lawyer or something." Anyway, we realized at that time we didn't have that picture, that it had been taken from us. I mean, we had let Featherstone look at it, you know, but we told no one they could reproduce it. They said, "Would you let us look at it and see if it could be reproduced?" We said, "Yes; you could look at it," we thought it was - you know, it was fuzzy and everything, but we were wanting to keep them and we suddenly realized we didn't have that picture, and that was quite a bit of money and we were getting pretty excited about it, and Mary was getting scared.

Arlen Specter: Did she eventually sell the picture, by the way?

Jean Hill: She sold the rights, the publishing rights of it, not the original picture, but they had already - AP and UP had already picked it up because Featherstone stole it.

Arlen Specter: Do you know what she sold those rights for?

Jean Hill: I think it was $600.

Arlen Specter: What did you tell Mark Lane besides about the picture?

Jean Hill: This is it.

Arlen Specter: Fine, go ahead.

Jean Hill: Anyway, when I realized we didn't have that picture and Mary was getting upset about that - by that time I had realized we were in a pressroom and that he had no right to be holding us and he had no authority and that we could get out of there, and they kept standing in front of the door, and I told him - I said, "Get out." We kept asking him for our picture, and where it was, and he said, We'll get it back - we'll get it back. And so I jerked away and ran out of the door and as I did, there was a Secret Service man. Now, this I was told - that he was a Secret Service man, and he said, "Do you have a red raincoat?" And, I said, "Yes; it's in yonder. Let me go." I was intent on finding someone to get that picture back and I said as I walked out, "I can get someone big enough to get it back for us." He said, "Does your friend have a blue raincoat?" And I said, "Yes; she's in there." He said, "Here they are," to somebody else and they told us that they had been looking for us.

Arlen Specter: Who told you that?

Jean Hill: This man.

Arlen Specter: All this you told Mr. Lane?

Jean Hill: Yes.

Arlen Specter: Go ahead.

Jean Hill: And so, then they took us into the police station. Just about that time Sheriff Decker came out and the man was with us and we were telling him why we were in there, why we had been in the pressroom, you know, and why they hadn't been able to find us, because they had thought that Mary had been hit and they were looking for the two women that were standing right by the car with the camera. At that time they didn't know what we were doing down there and why we were right at the car. So, there followed questioning all afternoon long, and he asked me at one time - well, in fact he asked repeatedly if I was held and I told him, "Yes."

Arlen Specter: Who asked you that?

Jean Hill: Mark Lane.

Arlen Specter: If you were held?

Jean Hill: Yes; you know if I were held, if I had to stay there and I told him, "Yes," but I told him when we were in the pressroom it was just our own ignorance, really, that was keeping us there and letting the man intimidate us that had no authority.

Arlen Specter: That was a newsman as opposed to the police official?

Jean Hill: Yes; and I gave Mark Lane his name several times - clearly. I remember clearly that I gave him his name.

Arlen Specter: And what name did you give him?

Jean Hill: Featherstone of the Times Herald, and so after we got out of there and I talked with a man.

Arlen Specter: Now, you are continuing to tell me everything you told Mark Lane?

Jean Hill: That's right, and I talked with this man, a Secret Service man, and I said, "Am I a kook or what's wrong with me?" I said, "They keep saying three shots - three shots," and I said, "I know I heard more. I heard from four to six shots anyway." He said, "Mrs. Hill, we were standing at the window and we heard more shots also, but we have three wounds and we have three bullets, three shots is all that we are willing to say right now."

(5) Jean Hill was interviewed by Mark Lane in 1964.

The FBI was here for days. They practically lived here. They just didn't like what I told them I saw and heard when the President was assassinated. She declined to permit a filmed interview, stating, for two years I have told the truth, but I have two children to support and I am a public school teacher.

My principal said it would be best not to talk about the assassination, and I just can't go through it all again. I can't believe the Warren Report. I know it's all a lie, because I was there when it happened, but I can't talk about it anymore because I don't want the FBI here constantly and I want to continue to teach here. I hope you don't think I'm a coward, but I cannot talk about the case anymore.

(6) Jim Featherston worked for the Dallas Times Herald in November, 1963. He later wrote about the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in the book, Secrets from the Sixth Floor Window (1994)

I ran to Dealey Plaza, a few yards away, and this is where I first learned the president had been shot. I found two young women, Mary Moorman and Jean Lollis Hill, near the curb on Dealey Plaza. Both had been within a few feet of the spot where Kennedy was shot, and Mary Moorman had taken a Polaroid picture of Jackie Kennedy cradling the president's head in her arms. It was a poorly focused and snowy picture, but, as far as I knew then, it was the only such picture in existence. I wanted the picture and I also wanted the two women's eyewitness accounts of the shooting.

I told Mrs. Moorman I wanted the picture for the Times Herald and she agreed. I then told both of them I would like for them to come with me to the courthouse pressroom so I could get their stories and both agreed... I called the city desk and told Tom LePere, an assistant city editor, that the president had been shot. "Really? Let me switch you to rewrite," LePere said, unruffled as if it were a routine story. I briefly told the rewrite man what had happened and then put Mary Moorman and Jean Lollis Hill on the phone so they could tell what they had seen in their own words. Mrs. Moorman, in effect, said was so busy taking the picture that she really didn't see anything. Mrs. Hill, however, gave a graphic account of seeing Kennedy shot a few feet in front of her eyes.

Before long, the pressroom became filled with other newsmen. Mrs. Hill told her story over and over again for television and radio. Each time, she would embellish it a bit until her version began to sound like Dodge City at high noon. She told of a man running up toward the now famed grassy knoll pursued by other men she believed to be policemen. In the meantime, I had talked to other witnesses and at one point I told Mrs. Hill she shouldn't be saying some of the things she was telling television and radio reporters. I was merely trying to save her later embarrassment but she apparently attached intrigue to my warning.

As the afternoon wore on, a deputy sheriff found out that I had two eyewitnesses in the pressroom, and he told me to ask them not to leave the courthouse until they could be questioned by law enforcement people. I relayed the information to Mrs. Moorman and Mrs. Hill.

All this time, I was wearing a lapel card identifying myself as a member of the press. It was also evident we were in the pressroom and the room was so designated by a sign on the door.

I am mentioning all this because a few months later Mrs. Hill told the Warren Commission bad things about me. She told the commission that I had grabbed Mrs. Moorman and her camera down on Dealey Plaza and that I wouldn't let her go even though she was crying. She added that I "stole" the picture from Mrs. Moorman. Mrs. Hill then said I had forced them to come with me to a strange room and then wouldn't let them leave. She also said I had told her what she could and couldn't say. Her testimony defaming me is all in Vol. VI of the Hearings Before the President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy, the Warren Report.

Why Mrs. Hill said all this has never been clear to me - I later theorized she got swept up in the excitement of having the cameras and lights on her and microphones shoved into her face. She was suffering from a sort of star-is-born syndrome, I later figured

(7) Mark Lane, Rush to Judgment (1966)

Mary Ann Moorman, an eyewitness to the assassination equipped with a Polaroid camera, was positioned in a strategic location in Dealey Plaza. She was standing with her friend, Jean Hill, across the street from and southwest of the Depository. Consequently, as she took a picture of the approaching motorcade the Book Depository formed the backdrop. Her camera was aimed, providentially, a trifle higher than the occasion demanded, and her photograph therefore contained a view of the sixth-floor of the building, including the alleged assassination window.

Mrs Moorman thus became a most important witness and her photograph an essential part of the evidence. Her presence at the scene and the fact that she did take the picture were vouched for by Mrs Hill when she testified before a Commission attorney. An FBI report filed by two agents discloses that they both interviewed Mrs Moorman on November 22.15 On that same day she signed an affidavit for the Dallas Sheriff's office. Deputy Sheriff John Wiseman submitted a report in which he said that he talked with Mrs Moorman that afternoon and that he took the picture from her. Wiseman stated that in examining the picture he could see the sixth-floor window from which the shots purportedly were fired."I took this picture to Chief Criminal Deputy Sheriff, Allan Sweatt, who later turned it over to Secret Service Officer Patterson," Wiseman said. A report submitted by Sweatt reveals that he also questioned Mrs Moorman and Mrs Hill on November 22 and that he received and examined the photograph. Sweatt said that "this picture was turned over to Secret Service Agent Patterson".

Since Mrs Moorman had used a Polaroid camera, the consequences were twofold: she was able to see the picture before it was taken from her by the police; she was not able to retain a negative. She told the FBI that the picture showed the Book Depository in the background, a fact confirmed by the two deputy sheriffs who also saw it.

Mrs Moorman was a witness with inordinately pertinent evidence to offer. Pictures of her in the act of photographing the motorcade appear in the volumes of evidence published by the Commission and in the Warren Commission Report itself. Yet the Report makes no mention of her or of her photograph; her name does not appear in the index to the Report. Although the Commission published many photographs, some of doubtful petinency it refused to publish the picture that possibility constituted the single most important item of evidence in establishing Oswald's innocence or guilt.

(8) John Costella, Mary Moorman and Her Polaroids, included in The Great Zapruder Film Hoax (edited by James H. Fetzer).

Jean (Hill) calls to JFK - looking down into the middle of the seat - as he approaches them. He turns, and perhaps starts to wave. Mary (Moorman) snaps a photo and then the first shot hits him. He jumps, and starts to slump forward. Jackie then responds, and cries out, as Jean and Mary reported. The limo stops somewhere down past the steps. There are then anywhere from two to seven further shots, that inflict the remaining wounds to JFK and Connally Jean sees the hair on the back of JFK's head flap up as his skull is blasted out. The limo speeds off. Mary is quickly intercepted and asked for her photos. She and Jean undergo hours of interrogation, after which they finally turn over the Polaroids. And the cover-up begins.

(9) Jean Hill, speech (November, 1991)

That area (of the Dealey Plaza) is sloping so when Mary reached up to take the picture, we did get a picture of the School Book Depository. We knew that, because we had a Polaroid camera, we were going to have to be quick if we wanted to take more than one picture. So what we planned was, Mary would take the picture, I would pull it out of the camera, coat it with fixative and put it in my pocket. That way we could keep shooting. When the head shot came, Mary fell down and the film (i.e., the famous photograph) was still in the camera. When the motorcade came around, there were so many voters on the other side (of Elm Street) that I knew the President was never going to look at me, so I yelled, "Hey Mr. President, I want to take your picture!" Just then his hands came up and the shots started ringing out. Then, in half the time it takes for me to tell it, I looked across the street and I saw them shooting from the knoll. I did get the impression that day that there was more than one shooter, but I had the idea that the good guys and the bad guys were shooting at each other. I guess I was a victim of too much television, because I assumed that the good guys always shot at the bad guys. Mary was on the grass shouting, "Get down! Get down! They're shooting! They're shooting!" Nobody was moving and I looked up and saw this man, moving rather quickly in front of the School Book Depository toward the railroad tracks, heading west, toward the area where I had seen the man shooting on the knoll. So, I thought to myself, "This man is getting away. I've got to do something. I've got to catch him." I jumped out into the street. One of the motorcyclists was turning his motor, looking up and all around for the shooter, and he almost ran me over. It scared me so bad, I went back to get Mary to go with me. She was still down on the ground. I couldn't get her to go, so I left her. I ran across and went up the hill. When I got there a hand came down on my shoulder, and it was a firm grip. This man said, "You're coming with me." And I said, "No, I can't come with you, I have to get this man." I'm not very good at doing what I'm told. He showed me I.D. It said Secret Service. It looked official to me. I tried to turn away from him and he said a second time, "You're going with me." At this point, a second man came and grabbed me from the other side, and they ran their hands through my pockets. They didn't say, "Do you have the picture? Which pocket?" They just ran their hands through my pockets and took it. They both held me up here (at the shoulder near the neck) someplace, where you could hurt somebody badly - and they told me, "Smile. Act like you're with your boyfriends." But I couldn't smile because it hurt too badly. And they said, "Here we go," each one holding me by a shoulder. They took me to the Records Building and we went up to a room on the fourth floor. There were two guys sitting there on the other side of a table looking out a window that overlooked "the killing zone," where you could see all of the goings on. You got the impression that they had been sitting there for a long time. They asked me what I had seen, and it became clear that they knew what I had seen. They asked me how many shots I had heard and I told them four to six. And they said, "No, you didn't. There were three shots. We have three bullets and that's all we're going to commit to now." I said, "Well, I know what I heard," and they told me, "What you heard were echoes. You would be very wise to keep your mouth shut." Well, I guess I've never been that wise. I know the difference between firecrackers, echoes, and gunshots. I'm the daughter of a game ranger, and my father took me shooting all my life.

(10) Dallas Morning News (November, 2000)

Jean Hill was the woman standing nearest to the car of President Kennedy at the moment of his assassination. In the famous Zapruder film and in Oliver Stone's motion picture "JFK", she appears in a bright red raincoat, stepping out to get the President's attention so her friend could snap his picture. The picture taken became one of the most well known photographs of the assassination...

She was the last living witness to the assassination whose testimony conflicted with the conclusions drawn by the Warren Commission. Her conflict with the findings of the Warren Commission led her to co-author an autobiography, which she titled "The Last Dissenting Witness".

She was featured prominently in the movie "JFK" and served as technical advisor to the director. Oliver Stone. Mr. Stone wrote the Forward to her book, and his film featured a character that portrayed Mrs. Hill. Her brave and interesting account of running up the "grassy knoll" (a term she coined in her testimony) to chase the man she believed was shooting at the President was riveting and controversial, and she was often in demand as a speaker.

(11) Washington Post (11th November, 2000)

"She loved the fact that she was a witness to history," Mrs. Hill's daughter Jeanne Poorman told the Reuters news service.

"With the inordinate number of people connected with witnessing the assassination who died in suspicious circumstances, she was proud that she was a survivor," Poorman said of her mother.

Poorman said her mother thought the shots came from the grassy knoll nearby, not the book depository across the street, and ran to the area thinking she would be able to spot the gunman.

Instead of catching up with the gunman, Mrs. Hill said, she was seized by two men in police uniforms and briefly taken into custody despite telling them she thought the assassin was running from the knoll.

(12) Bill Sloan, interviewed by the Sixth Floor Museum (31st July, 2001)

I met Jean, I guess, for the first time in probably 1990, and I didn’t think much about it... And you know, she said, “Well, I was an eyewitness to the assassination,” and that was where it laid. Then, it was in early ’91, I guess… Oliver Stone brought his film production crew to Dallas to film JFK… I mean, Jean reveled in this. She loved to be in the limelight, and Oliver came to her house for dinner and brought his whole entourage, and it was just, you know, it was the biggest moment of her life. And he made her a consultant to the picture, and you know, she had carte blanche… And one day, early in, like, February of ’91, my wife, Lana, came home from school and said, “Jean wants to know if you would have any interest at all in writing her book.” And I said, “No.” But she talked me into meeting with Jean, and Jean came over to the house and we sat down together… and we talked for a long time. And after meeting her on several occasions, I finally said, “OK, I’ll, you know, I’ll give it a shot. I’ll try to write the book...

I will mention that I’m the only journalist that was working in Dallas that day that I have ever heard of that believes that there was a conspiracy in the assassination, and I do believe that. I mean, I’ve never been able to subscribe to any of the major theories. I don’t know whodunit. I don’t know whether it was the Russians or the pro-Castro Cubans or the anti-Castro Cubans or the Republicans or who it was, you know. But I just simply believe that it was too enormous a thing for Lee Harvey Oswald to have carried the whole thing out himself. And to that extent, I believe it was a conspiracy, but I believe that there was a great, great conspiracy in the cover-up that followed the assassination, and I think that many, many government officials and agencies were involved in that aspect of it.