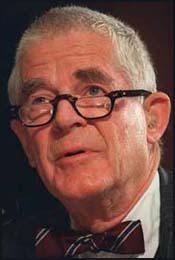

Archibald Cox

Archibald Cox, the son of a lawyer, was born on 17th May, 1912. An outstanding student, in 1937 Cox graduated top of his class at Harvard Law School. He joined Ropes, Gray, Best, Coolidge and Rugg, a Boston law firm and concentrated on industrial relations cases. During the Second World War Cox moved to Washington and worked as a solicitor in the Labour department.

After the war Cox joined the Harvard teaching staff. His knowledge of labour law meant that the government regularly used him in collective bargaining disputes.

A member of the Democratic Party Cox worked as an adviser and speech-writer for John Kennedy during the 1960 presidential election. Kennedy rewarded Cox by appointing him solicitor general. A strong advocate of civil rights, Cox helped Robert Kennedy, the attorney general, to discover legal remedies to deal with cases of injustice.

Cox continued in this post under President Lyndon Johnson and helped to draft the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Despite this, Johnson sacked him as his solicitor general. The Washington Post commented that he had filled his office "with extraordinary devotion, learning, effectiveness, and style". Cox now resumed his teaching career at Harvard.

Cox returned to national politics when on 18th May, 1973, Attorney General Elliot Richardson appointed him as special prosecutor, with unprecedented authority and independence to investigate the alleged Watergate cover-up and illegal activity in the 1972 presidential campaign.

On 25th June, 1973, John Dean testified that at a meeting with Richard Nixon on 15th April, the president had remarked that he had probably been foolish to have discussed his attempts to get clemency for E. Howard Hunt with Charles Colson. Dean concluded from this that Nixon's office might be bugged. On Friday, 13th July, Alexander P. Butterfield appeared before the committee and was asked about if he knew whether Nixon was recording meetings he was having in the White House. Butterfield reluctantly admitted details of the tape system which monitored Nixon's conversations.

Alexander P. Butterfield also said that he knew "it was probably the one thing that the President would not want revealed". This information did indeed interest Cox and he demand that Richard Nixon hand over the White House tapes. Nixon refused and so Cox appealed to the Supreme Court.

On 20th October, 1973, Nixon ordered his Attorney-General, Elliot Richardson, to fire Cox. Richardson refused and resigned in protest. Nixon then ordered the deputy Attorney-General, William Ruckelshaus, to fire Cox. Ruckelshaus also refused and he was sacked. Eventually, Robert Bork, the Solicitor-General, fired Cox.

An estimated 450,000 telegrams went sent to Richard Nixon protesting against his decision to remove Cox. The heads of 17 law colleges now called for Nixon's impeachment. Nixon was unable to resist the pressure and on 23rd October he agreed to comply with the subpoena and began releasing some of the tapes. The following month a gap of over 18 minutes was discovered on the tape of the conversation between Nixon and H. R. Haldeman on June 20, 1972. Nixon's secretary, Rose Mary Woods, denied deliberately erasing the tape. It was now clear that Nixon had been involved in the cover-up and members of the Senate began to call for his impeachment.

Peter Rodino, who was chairman of the Judiciary Committee, presided over the impeachment proceedings against Nixon. The hearings opened in May 1974. The committee had to vote on five articles of impeachment and it was thought that members would split on party lines. However, on the three main charges - obstructing justice, abuse of power and withholding evidence, the majority of Republicans voted with the Democrats.

Two weeks later three senior Republican congressmen, Barry Goldwater, Hugh Scott, John Rhodes visited Richard Nixon to tell him that they were going to vote for his impeachment. Nixon, convinced that he will lose the vote, decided to resign as president of the United States.

On 9th August, 1974, Richard Nixon became the first President of the United States to resign from office. Nixon was granted a pardon but several members of his staff involved in the cover-up were imprisoned. This included: H. R. Haldeman, John Ehrlichman, Charles Colson, John Dean, John N. Mitchell, Jeb Magruder, Herbert W. Kalmbach, Egil Krogh, Frederick LaRue, Robert Mardian and Dwight L. Chapin.

After Watergate, Cox taught law at Harvard and Boston universities. He also served as the chairman of Common Cause, a nonprofit lobbying organization that focuses on campaign finance reform.

Archibald Cox died on 29th May, 2004 in Brooksville, Maine.

Primary Sources

(1) Bart Barnes, Washington Post (30th May, 2004)

In October 1973, Cox precipitated what would become known as the "Saturday night massacre." He did this by insisting on unrestricted access to tape recordings of presidential conversations in the Oval Office during the period immediately after five men with links to Nixon's Committee to Re-elect the President had been arrested in the June 1972 break-in at the Watergate headquarters of the Democratic National Committee.

An angry Nixon demanded Cox's firing. But Attorney General Elliot Richardson, who had recruited Cox as the Watergate special prosecutor, refused to carry out the president's order. He resigned, as did his deputy, William D. Ruckelshaus. Robert H. Bork, who as solicitor general was the third-ranking officer of the Justice Department, dismissed Cox.

Almost overnight, from Capitol Hill and in the national media, came the sounds of protest and dismay. Sen. Barry M. Goldwater (Ariz.), one of the most influential Republicans in Congress, declared that Nixon's credibility "has reached an all-time low from which he may not be able to recover."

In the House of Representatives, members introduced 22 bills calling for the impeachment of the president or an investigation into impeachment proceedings. More than a million telegrams demanding impeachment poured into congressional offices.

Newspaper editorial writers and columnists made somber references to an "attempted coup d'etat." Cox appeared on the cover of Newsweek magazine, wearing his trademark bow tie, neatly knotted as always. Time had photos of Cox and the president facing each other over the caption, "Nixon on the Brink."

The firing of Cox, on Oct. 20, 1973, came at a time of high turbulence and political unrest. The Watergate scandal was increasingly engulfing the Nixon presidency. A summer of televised hearings on Capitol Hill had produced a steady flow of testimony suggesting burglary, lies, duplicity and criminality at the highest levels.

(2) Harold Jackson, The Guardian (31st May, 2004)

The lawyer acting for President Nixon at the federal court hearing on August 22 1973 assured Judge John Sirica that "in the 184 years of this republic no court has undertaken to do any of the things the special prosecutor contends that this court ought to do". The opponent he was flailing was Professor Archibald Cox of Harvard, who has died aged 92.

Cox had agreed to serve as the Watergate special prosecutor after seven eminent lawyers had rejected the increasingly desperate invitations of President Nixon's new attorney general. They plainly saw the job as a bed of nails and Cox now seemed to be proving their point.

Against massive political and legal obstruction, he was trying to obtain some of the White House's most confidential material, hoping it would expose President Nixon's part in the attempted cover up of this historic "third-rate burglary". This was the June 1972 break-in at the Democratic national committee's offices in the Watergate office complex at the height of the president's re-election campaign.

The scandal was racking the country. Though three of Nixon's senior staff had been sacked, the president was refusing to surrender any of the Oval Office recordings of conversations he had had with them about the break-in. His lawyers argued that Cox's request breached the constitutional separation of powers between judiciary and executive. They had some reason for optimism. At a later hearing Judge Sirica did, in fact, reject a parallel request by the Senate Watergate committee for access to the tapes...

On October 19 1973 Nixon ordered Cox to abandon his suit. The lawyer refused, saying that: "For me to comply with those instructions would violate my solemn pledge to the Senate and the country." Next afternoon came the infamous Saturday Night Massacre.

Nixon instructed his attorney general, Elliot Richardson, to sack Cox and to close down his operation. Richardson refused and resigned, as did his deputy William Ruckelshaus. Finally the solicitor general, Robert Bork, carried out the instruction...

It turned Cox into a folk hero, but he drew little satisfaction from his role. "I'm worried," he told reporters, "that I am getting too big for my breeches, that what I see as principle could be vanity." He then returned thankfully to the academic world to watch his successor, Leon Jaworski, force Nixon out.