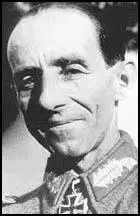

Rudolf von Senger

Fridolin von Senger was born in Germany on 4th September 1891. After attended Eton College he became a Rhodes scholar (1912-14). He joined the German Army on the outbreak of the First World War and was commissioned as a second lieutenant.

After the war he remained in the army and joined the Reichswehr's horse cavalry. A world-class equestrian he taught at the Hanover Calvary School (1919-21) and then worked with the cavalry inspectorate in Berlin.

In 1938 Senger became commander of the 3rd Cavalry Regiment and the following year was promoted to the rank of colonel. He led the regiment in the invasion of Poland and in 1940 he took command of a motorized brigade during the Western Offensive. For the next two years he was chief liaison officer with the Franco-Italian armistice commission.

In September 1941 he was promoted to major general he was sent to the Soviet Union to command the 17th Panzer Division where he served under General Herman Hoth. The following year he took part in the campaign in the Ukraine under Field Marshal Erich von Manstein.

Promoted to lieutenant general he was sent to support the Italian Army in Sicily in May 1943. Along with Hans Hube he helped to coordinate efforts against the Allies and in October replaced Hube as commander of the 14th Panzer Corps. This included the defence of Monte Cassino.

Senger was a prisoner of war from 22nd May 1945 to 18th May 1946. After his release he published his autobiography, Neither Fear or Hope (1960). Fridolin von Senger died in 1963.

Primary Sources

(1) Fridolin von Senger was interviewed by Basil Liddell Hart about the invasion of Sicily in his book The Other Side of the Hill (1948)

The Italian-German High Command had, correctly, regarded the south-east comer of the island as the most likely part for landing. It had, however, looked chiefly upon the coastal plains near Gda on the south coast and Catania on the east coast as the most threatened by enemy invasion. These two plans seemed to be the only ones for the employment of armoured formations, as they promised room for deployment from the very moment of the landing, or at least during further advance towards the centre of the island. This view of the details was mistaken. The Allied landing, which took place on 10th July, extended over the whole of the southeast coast from Syracuse to Licata. It appears that nowhere along this stretch could landings of tank units be seriously checked by the coast defence forces. These forces were second or third-rate Italian divisions, badly equipped and not backed by any coast batteries fit for this task.

Allied tank units accordingly advanced mainly on the roads. They could do so rather rapidly as long as they were backed by their naval artillery and by their air forces. As they were backed by superior air forces also, they made good advances even at later stages where they lacked support by naval artillery and where ground conditions were most unsuitable for mobile tank warfare. Owing to difficult ground conditions, however, they never succeeded in breaking through organized Axis defence lines as had often been the case both in Russia and in Africa, nor did they ever annihilate beaten Axis forces by pursuing them - which they might have done easily on ground more suitable, as in Russia or Africa.

(2) General Fridolin von Senger fought under Albert Kesselring at Monte Cassino.

Field-Marshal Kesselring had given express orders that no German soldier should enter the Monastery, so as to avoid giving the Allies any pretext for bombing or shelling it. I cannot testify personally that this decision was communicated to the Allies but I am sure that the Vatican found means to do so, since it was so directly interested in the fate of Monte Cassino. Not only did Field-Marshal Kesselring prohibit German soldiers from entering the Monastery, but be also placed a guard at the entrance gate to ensure that his orders were carried out.