Trench Mud

In September, 1914, the German commander, General Erich von Falkenhayn ordered his men to dig trenches that would provide them with protection from the advancing French and British troops. As the Allies soon realised that they could not break through this line, they also began to dig trenches.

As the Germans were the first to decide where to stand fast and dig, they had been able to choose the best places to build their trenches. The possession of the higher ground not only gave the Germans a tactical advantage, but it also forced the British to live in the worst conditions. Most of this area was rarely a few feet above sea level. As soon as soldiers began to dig down they would invariably find water two or three feet below the surface. Along the whole line, trench life involved a never-ending struggle against water and mud. Duck-boards were placed at the bottom of the trenches to protect soldiers from problems such as trench foot.

Captain Alexander Stewart pointed out that: "Mud is a bad description as the soil was more like a thick slime than mud. When walking one sank several inches in and owing to the suction, it was difficult to withdraw the feet. The consequence was that men who were standing still or sitting down got embedded in the slime and were unable to extricate themselves."

Much of the land where the trenches were dug was either clay or sand. The water could not pass through the clay and because the sand was on top, the trenches became waterlogged when it rained. The trenches were hard to dig and kept on collapsing in the waterlogged sand. As well as trenches the shells from the guns and bombs made big craters in the ground. The rain filled up the craters and then poured into the trenches.

Bruce Bairnsfather recorded his experiences in the trenches: "It was quite the worse trench I have ever seen. A number of men were in it, standing and leaning, silently enduring the following conditions. It was quite dark. The enemy were about two hundred yards away, or rather less. It was raining, and the trench contained over three feet of water. The men, therefore, were standing up to the waist in water. The front parapet was nothing but a rough earth mound which, owing to the water about, was practically non-existent. They were all wet through and through, with a great deal of their equipment below the water at the bottom of the trench. There they were, taking it all as a necessary part of a great game; not a grumble nor a comment."

J. B. Priestley wrote a letter to his father describing what it was like on the Western Front: "The communication trenches are simply canals, up to the waist in some parts, the rest up to the knees. There are only a few dug-outs and those are full of water or falling in. Three men were killed this week from falling dug-outs. I haven't had a wash since we came into these trenches and we are all mud from head to foot." Vyvyan Harmsworth, the son of Lord Rothermere, added: "Hell is the only word descriptive of the weather out here and the state of the ground. It rains every day! The trenches are mud and water up to one's neck, rendering some impassable - but where it is up to the waist we have to make our way along cheerfully. I can tell you - it is no fun getting up to the waist and right through, as I did last night. Lots of men have been sent off with slight frost-bite - the foot swells up and gets too big for the boot."

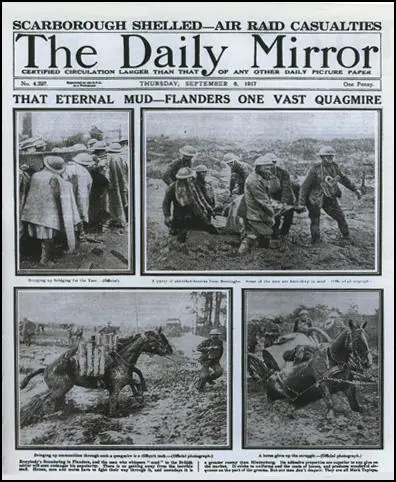

A copy of this newspaper can be obtained from Historic Newspapers.

Guy Chapman was another soldier who was troubled by the mud: "Rain had made our bare trenches a quag, and earth, unsupported by revetments, was beginning to slide to the bottom. We hailed the first frost which momentarily arrested our ruin. Saps filled up and had to be abandoned. The cookhouse disappeared. Dugouts filled up and collapsed. The few duckboards floated away, uncovering sump-pits into which the uncharted wanderer fell, his oaths stifled by a brownish stinking fluid."

The mud was especially hated by the stretcher-bearers. As Harold Chapin pointed out in a letter to Alice Chapin in May 1915: "It took six of us to carry one man. You have no idea of the physical fatigue entailed in carrying a twelve stone man a thousand yards across muddy fields."

Primary Sources

(1) Captain Impey of the Royal Sussex Regiment wrote this account in 1915.

The trenches were wet and cold and at this time some of them did not have duckboards or dug-outs. The battalion lived in mud and water.

(2) Private Livesay, letter to parents living in East Grinstead (6th March, 1915)

Our trenches are... ankle deep mud. In some places trenches are waist deep in water. Time is spent digging, filling sandbags, building up parapets, fetching stores, etc. One does not have time to be weary.

(3) Private Pollard wrote about trench life in his memoirs published in 1932.

The trench, when we reached it, was half full of mud and water. We set to work to try and drain it. Our efforts were hampered by the fact that the French, who had first occupied it, had buried their dead in the bottom and sides. Every stroke of the pick encountered a body. The smell was awful.

(4) J. B. Priestley, letter to his father, Jonathan Priestley (December, 1915)

The communication trenches are simply canals, up to the waist in some parts, the rest up to the knees. There are only a few dug-outs and those are full of water or falling in. Three men were killed this week from falling dug-outs. I haven't had a wash since we came into these trenches and we are all mud from head to foot.

(5) Bruce Bairnsfather, Bullets and Billets (1916)

It was quite the worse trench I have ever seen. A number of men were in it, standing and leaning, silently enduring the following conditions. It was quite dark. The enemy were about two hundred yards away, or rather less. It was raining, and the trench contained over three feet of water. The men, therefore, were standing up to the waist in water. The front parapet was nothing but a rough earth mound which, owing to the water about, was practically non-existent. They were all wet through and through, with a great deal of their equipment below the water at the bottom of the trench. There they were, taking it all as a necessary part of a great game; not a grumble nor a comment.

(6) Captain Lionel Crouch wrote to his wife about life in the trenches in 1917.

Last night we had the worst time we've had since we've been out. A terrific thunderstorm broke out. Rain poured in torrents, and the trenches were rivers, up to one's knees in places and higher if one fell into a sump. One chap fell in one above his waist! It was pitch dark and all was murky in the extreme. Bits of the trench fell in. The rifles all got choked with mud, through men falling down.

(7) Guy Chapman, A Passionate Prodigality: Fragments of Autobiography (1933)

Rain had made our bare trenches a quag, and earth, unsupported by revetments, was beginning to slide to the bottom. We hailed the first frost which momentarily arrested our ruin. Saps filled up and had to be abandoned. The cookhouse disappeared. Dugouts filled up and collapsed. The few duckboards floated away, uncovering sump-pits into which the uncharted wanderer fell, his oaths stifled by a brownish stinking fluid.

(8) Vyvyan Harmsworth, letter to Lord Rothermere (13th January, 1915)

Hell is the only word descriptive of the weather out here and the state of the ground. It rains every day! The trenches are mud and water up to one's neck, rendering some impassable - but where it is up to the waist we have to make our way along cheerfully. I can tell you - it is no fun getting up to the waist and right through, as I did last night. Lots of men have been sent off with slight frost-bite - the foot swells up and gets too big for the boot.

(9) Harold Chapin, letter to Calypso Chapin (23rd May 1915)

I have been up to my eyes in work (at the main dressing station in " ----- ") since Sunday morning when the British and French attack began (or rather when its fruits in wounded began to reach us. The actual attack began on Saturday night). Nominally I have been on night duty in the operating tent, but naturally with wounded and wounded and wounded flowing in neither night nor day duty means anything. I had had eight hours sleep in three days, when heavy fighting out here developed and the message came down for more bearers, so out I came with a dozen others by horse ambulance (time two a.m.) and going on on foot just as day was breaking, found a Regimental M.O. in a room in a gutted house with some half dozen wounded and two or three dead on the floor about him. His own regimental stretcher bearers were carrying and carrying the long mile down to a spot where an ambulance could meet them, in comparative safety. I gave a hand with my party of six and between us we carried down two: you have no idea of the physical fatigue entailed in carrying a twelve stone blessé a thousand odd yards across muddy fields. Oh this cruel mud! Back in " ----- " we hate it (the poor fellows come in absolutely clayed up), but out here, it is infernal.

It clings and sucks at your boots; weighs you down; chills you and, drying in upper garments, makes them chafe. The dead lie in it in queer flat - jacent - attitudes. They nearly always look flung down rather than fallen, their feet turned sideways lie flatter than a living man's could, and the thighs splayed out lower the contours of the back. An unrelieved level of liquid mud seems to be the end of war.

(10) Oliver Lyttelton, letter home (21st June, 1915)

The whole place was a sea of mud, and the scene still remains incoherent in my memory, plunging about for overworked stretcher bearers, falling into shell-holes, losing our way, wet and tired, we felt all the time rather impotent. But the work was done. All the wounded, including some of the Scots Guards who had lain out for forty-eight hours, were brought in and most of the dead buried. Some (I think it was three) died before we could get stretchers to take them back to the dressing station or on their way there. You see it takes four men to carry one wounded man and each journey to the dressing station could not be accomplished under four hours. This sounds rather incredible but no one realizes the difficulty of getting about, even for a man unhampered by anything. One mile an hour is good going in the mud for an officer, and you will always find yourself on the right when something has to be done on the left. No light can be shown, and you feel your way for about thirty yards as a rule before falling into a ditch or a shell-hole.

(11) Captain Alexander Stewart, journal entry (1916)

This part of the line was up to then the worst in which I had been. I refer more particularly to the mud and water. All the land had been very churned up by shell explosions, and for many days the weather had been wet. It was not possible to dig for more than about a foot without coming to water. Mud is a bad description as the soil was more like a thick slime than mud. When walking one sank several inches in and owing to the suction, it was difficult to withdraw the feet. The consequence was that men who were standing still or sitting down got embedded in the slime and were unable to extricate themselves. As the trenches were so shallow men had to stay where they were all day. Most of the night we had to spend digging and pulling men out of the mud. It was only the legs that got stuck; the body being lighter and larger lay on the surface. To dig a man out the only way was to put duck boards on each side of him and then work at one leg, digging poking, and pulling, until the suction was relieved. Then a strong pull by three or four men would get one leg out and work would be begun on the other. Back to Battalion Headquarters was about 800 yards. At night it would take a “runner” (i.e. an orderly taking messages) about two hours to get there. Going to and from Battalion Headquarters from the line, one would hear men who had missed their way and got stuck in the mud calling out for help that often could not be sent to them. It would be useless for only one or two men to go to help them, and practically all the troops were in the front line and had, of course, to stay there. All the time the Boche dropped shells promiscuously about the place. He who had a corpse to stand or sit on was lucky.

(12) General Eric Ludendorff, My War Memories, 1914-1918 (1920)

The fifth act of the great drama in Flanders opened on the 22nd October. Enormous masses of ammunition, such as the human mind had never imagined before the war, were hurled upon the bodies of men who passed a miserable existence scattered about in mud-filled shell-holes. The horror of the shell-hole area of Verdun was surpassed. It was no longer life at all. It was mere unspeakable suffering. And through this world of mud the attackers dragged themselves, slowly, but steadily, and in dense masses. Caught in the advanced zone by our hail of fire they often collapsed, and the lonely man in the shell-hole breathed again. Then the mass came on again. Rifle and machine-gun jammed with the mud. Man fought against man, and only too often the mass was successful.

(13) Frank Percy Crozier, A Brass Hat in No Man's Land (1930)

We go in to the trenches for four days, while the weather becomes atrocious. It is notorious that French trenches are seldom good and these are no exceptions. Because there is no revetting, walls of fire and communication trenches fall in, so-called dugouts collapse, and telephone wires connecting companies and brigade become non-effective, consequent on the landslide. The men are up to their waists in mud and water. Rats drown and rations cannot be got up.