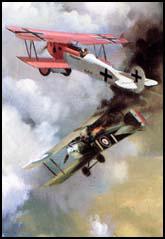

Dogfights

The early definition of the word 'dogfight' meant an aerial battle between two or more aircraft. As the First World War broke out not long after the aeroplane had been invented, there had not been time to develop guns which could be built into the body of a plane. The first fighter planes were only equipped with machine-guns which were fixed onto the top wing.

These early fighter aircraft had two two seats, with a man sitting in the rear controlling the guns. Dogfights were extremely difficult because the pilot would have to dodge other enemy aircraft while listening to the commands of the gunner as to where to fly to get the enemy into his sights.

The first dog-fight is believed to have taken place on 28th August 1914, when Lieutenant Norman Spratt, flying a Sopwith Tabloid, forced down a German two-seater. This was an amazing achievement as his Sopwith was not armed.

One of Britain's first star pilots was Louis Strange. He devised a safety strap system in his Avro 504 so that it was possible for his gunner to "stand up and fire all round over the top of the plane and behind". Strange's gunner, Rabagliati, used a Lewis Gun and was soon bring down German aircraft over the Western Front. By October 1915 the Royal Flying Corps decided to fit this safety harness to all their aircraft. As well as using guns, some crews carried grenades which they tried to drop onto enemy fliers below them.

The first Victoria Cross for air combat was won by Captain Lanoe Hawker on 25th June, 1915. Flying a single-seater Bristol Scout and armed with a single-shot cavalry carbine mounted on the starboard side of the fuselage, Hawker attacked an enemy two-seater over Ypres. After forcing it to land he brought down two more enemy planes. What made the achievement so remarkable was that all three German aircraft were armed with machine-guns.

In 1915 the French pilot, Roland Garros, added deflector plates to the blades of his propeller. These small wedges of toughened steel diverted the passage of those bullets which struck the blades. It was now possible for a pilot in a single-seater aircraft to successfully fire a machine-gun.

Anton Fokker, a Dutch designer who had set up an aircraft factory in Schwerin, German, was also trying to develop a machine-gun that could fire through revolving propeller blades. By the autumn of 1915 Fokker was fitting his Eindecker monoplanes with interrupter gear, therefore producing the first true fighter aircraft. Also called a synchronising gear, the propeller was linked by a shaft to the trigger to block fire whenever they were in line.

German pilots such as Max Immelmann and Oswald Boelcke began destroying large numbers of British aircraft using their synchronised machine-guns. Immelmann destroyed seventeen Allied aircraft in his Eindecker before being shot down and killed on 15 June 1916. Boelcke went on to claim forty victims before he was also killed in October 1916. Pilots such as Immelmann and Boelcke, who had more than eight 'kills', became known as Flying Aces. It was not long before Britain and France began fitting synchronised machine-guns to their aircraft and pilots such as Rene Fonck and William Bishop developed reputations as flying aces.

By the spring of 1916 the British had produced the Avro DH2 fighter plane. The DH2 was a single-seater biplane with the engine behind the pilot. It carried a forward-firing Lewis machine-gun and the absence of an engine in front gave the pilot and uninterupted view of his target.

Another important innovation was the development of tracer ammunition. The Royal Flying Corps began using it in July 1916 and its pilots found it very useful. With every seventh round a tracer was fired so the gunner-pilot could see his stream of fire and adjust his aim accordingly.

Organisation and tactics changed with the introduction of the synchronized machine-gun. At first flying aces adopted "lone wolf" tactics. However, by 1917 British pilots tended to seek out enemy aircraft in groups of six. The flight commander would be in front, with an aircraft on either side forming a V shape. To the rear and above were two other planes and at the back was the sub-leader. However, when in combat, the pilots operated in pairs, one to attack, and the other to defend. German pilots preferred larger formations and these were later known as circuses.

One of the most important figures in the development of dogfight tactics was Major Mick Mannock. Between May 1917 and his death in July 1918, Mannock became Britain's leading flying ace with seventry-three victories. When attacking, the best tactic was to dive upon the target out of the sun. This strategy reduced the time that the pilot being attacked could bank or dive and avoid being hit. Later in the war some observers fixed mirrors in line with their gun, which could them be used to reflect the rays of the sun back into the eyes of the attacking pilot.

Fighter pilots also made good use of cloud-cover. This enabled a pilot to attack the enemy and quickly return to the safety of the cloud. Pilots did not have long to destroy their target. Fighter aircraft at that time only carried enough ammunition to fire at the enemy for about fifty seconds. Therefore pilots had to make sure they used their machine-guns wisely. Rene Fonck, the French flying ace, usually took no more than five or six rounds to down an enemy aircraft.

Almost all the pilots involved in flying aircraft in the First World War were under the age of twenty-five. As the death-rate was very high by 1918 a large proportion of the pilots were aged between eighteen and twenty-one. Pilots were sent into combat after only some thirty hours of air training. Training in how to take part in dogfights had to be given by the more experienced pilots at the battle front.

Primary Sources

(1) Louis Strange, diary entry (2nd October, 1914)

I fixed a safety strap to leading edge of top plane so as to enable passenger to stand up and fire all round over top of plane and behind. Took Lieutenant Rabagliati as my passenger on trial trip; great success. Increases range of fire greatly and I hear that these belts are to be fitted to all machines.

(2) Oswald Boelcke, Germany's leading flying ace in 1916, gave instructions on how to attack enemy aircraft.

(1) Always try to secure an advantageous position before attacking. Climb before and during approach in order to surprise the enemy from above, and dive on him swiftly from the rear when the moment to attack is at hand.

(2) Try to place yourself between the sun and the enemy. This puts the glare of the sun in the enemy's eyes and makes it difficult to see you and impossible for him to shoot with any accuracy.

(3) Do not fire the machine guns until the enemy is within range and you have him squarely within your sights.

(4) Attack when the enemy least expects it or when he is preoccupied with other duties such as observation, photography or bombing.

(5) Never turn your back and try to run away from an enemy fighter. If you are surprised by an attack on your tail, turn and face the enemy with your guns.

(6) Keep your eyes on the enemy and do not let him deceive you with tricks. If your opponent appears damaged, follow him down until he crashes to be sure he is not faking.

(3) In his book, Red Air Fighter, Manfred von Richthofen, described killing Lanoe George Hawker.

In view of the character of our fight it was clear to me that I had been tackling a flying champion. One day I was blithely flying to give chase when I noticed three Englishmen who also had apparently gone a-hunting. I noticed that they were watching me and as I felt much inclination to have a fight I did not want to disappoint them.

I was flying at a lower altitude. Consequently I had to wait until one of my English friends tried to drop on me. After a short while one of the three came sailing along and attempted to tackle me in the rear. After firing five shots he had to stop for I had swerved in a sharp curve.

The Englishman tried to catch me up in the rear while I tried to get behind him. So we circled round and round like madmen after one another at an altitude of about 10,000 feet.

First we circled twenty times to the left, and then thirty times to the right. Each tried to get behind and above the other. Soon I discovered that I was not meeting a beginner. He had not the slightest intention of breaking off the fight. He was traveling in a machine which turned beautifully. However, my own was better at rising than his, and I succeeded at last in getting above and beyond my English waltzing partner.

When we had got down to about 6,000 feet without having achieved anything in particular, my opponent ought to have discovered that it was time for him to take his leave. The wind was favorable to me for it drove us more and more towards the German position. At last we were above Bapaume, about half a mile behind the German front. The impertinent fellow was full of cheek and when we had got down to about 3,000 feet he merrily waved to me as if he would say, "Well, how do you do?"

The circles which we made around one another were so narrow that their diameter was probably no more than 250 or 300 feet. I had time to take a good look at my opponent. I looked down into his carriage and could see every movement of his head. If he had not had his cap on I would have noticed what kind of a face he was making.

My Englishmen was a good sportsman, but by and by the thing became a little too hot for him. He had to decide whether he would land on German ground or whether he would fly back to the English lines. Of course he tried the latter, after having endeavored in vain to escape me by loopings and such like tricks. At that time his first bullets were flying around me, for hitherto neither of us had been able to do any shooting.

When he had come down to about three hundred feet he tried to escape by flying in a zig-zag course during which, as is well known, it is difficult for an observer to shoot. That was my most favorable moment. I followed him at an altitude of from two hundred and fifty feet to one hundred and fifty feet, firing all the time. The Englishman could not help falling. But the jamming of my gun nearly robbed me of my success.

My opponent fell, shot through the head, one hundred and fifty feet behind our line

(4) In a letter that he wrote just before his death on 12th May 1917, Lieutenant Dolan described a training session with his commanding officer, Major Mick Mannock.

On 30th April 1917 Mick took me up to 'see me right' as he put it. Near Poperinghe, we spotted a Hun two-seater. Instead of signaling for me to go down with him, he told me to stay where I was. All signals are given by hand-movements and moving the aircraft in various ways. By this time we were circling around the Hun and had the sun behind us. When we were almost directly ahead of the Hun, down goes Mick like a rocket. He positioned himself so that the pilot could not see him because of the upper wing, and the observer was looking the other way for the expected form of attack from the rear. He gave it a quick burst and then pulled up a long, curving climb to join me. As he pulled alongside, he waved his arm down at the running German and nodded at me to get it. I went down on the Hun's tail and saw that Mick had killed the gunner, and I could attack safely. He had set the Hun up for me and deliberately killed the gunner to ensure that I got my kill.

(5) H. G. Clements wrote an account of Major Mick Mannock in 1981.

The fact that I am still alive is due to Mick's high standard of leadership and the strict discipline on which he insisted. We were all expected to follow and cover him as far as possible during an engagement and then to rejoin the formation as soon as that engagement was over. None of Mick's pilots would have dreamed of chasing off alone after the retreating enemy or any other such foolhardy act. He moulded us into a team, and because of his skilled leadership we became a highly efficient team. Our squadron leader said that Mannock was the most skillful patrol leader in World War I, which would account for the relatively few casualties in his flight team compared with the high number of enemy aircraft destroyed.

(6) In a letter that he wrote just before his death on 12th May 1917, Lieutenant Dolan explained the dogfight tactics employed by Major Mick Mannock.

Mick goes down on his prey like a hawk. The Huns don't know what's hit them until it's too late to do anything but go down in bits. He goes down vertically at a frightening speed and pulls out at the last moment. He opens fire when only yards away and zooms up over the Huns and turns back for another crack at the target if necessary.

(7) Edward Rickenbacker, Fighting the Flying Circus (1919)

There was a scout coming towards us from north of Pont-à-Mousson. It was at about our altitude. I knew it was a Hun the moment I saw it, for it had the familiar lines of their new Pfalz. More. over, my confidence in James Norman Hall was such that I knew he couldn't make a mistake. And he was still climbing into the sun, carefully keeping his position between its glare and the oncoming fighting plane I clung as closely to Hall as I could. The Hun was steadily approaching us, unconscious of his danger, for we were full in the sun.

With the first downward dive of Jimmy's machine I was by his side. We had at least a thousand feet advantage over the enemy and we were two to one numerically. He might outdive our machines, for the Pfalz is a famous diver, while our faster climbing Nieuports had a droll little habit of shedding their fabric when plunged too furiously through the air. The Boche hadn't a chance to outfly us. His only salvation would be in a dive towards his own lines.

These thoughts passed through my mind in a flash and I instantly determined upon my tactics. While Hall went in for his attack I would keep my altitude and get a position the other side of the Pfalz, to cut off his retreat.

No sooner had I altered my line of flight than the German pilot saw me leave the sun's rays. Hall was already half-way to him when he stuck up his nose and began furiously climbing to the upper ceiling. I let him pass me and found myself on the other side just as Hall began firing. I doubt if the Boche had seen Hall's Nieuport at all.

Surprised by discovering this new antagonist, Hall, ahead of him, the Pfalz immediately abandoned all idea of a battle and banking around to the right started for home, just as I had expected him to do. In a trice I was on his tail. Down, down we sped with throttles both full open. Hall was coming on somewhere in my rear. The Boche had no heart for evolutions or maneuvers. He was running like a scared rabbit, as I had run from Campbell. I was gaining upon him every instant and had my sights trained dead upon his seat before I fired my first shot.

At 150 yards I pressed my triggers. The tracer bullets cut a streak of living fire into the rear of the Pfalz tail. Raising the nose of my aeroplane slightly the fiery streak lifted itself like the stream of water pouring from a garden hose. Gradually it settled into the pilot's seat. The swerving of the Pfalz course indicated that its rudder no longer was held by a directing hand. At 2000 feet above the enemy's lines I pulled up my headlong dive and watched the enemy machine continuing on its course. Curving slightly to the left the Pfalz circled a little to the south and the next minute crashed onto the ground just at the edge of the woods a mile inside their own lines. I had brought down my first enemy aeroplane and had not been subjected to a single shot!

(8) Diary of a pilot based on the Western Front (28th July 1918)

I can't write much these days. I'm too nervous. I can hardly hold a pen. I'm all right in the air, as calm as a cucumber, but on the ground I'm a wreck and I get panicky. Nobody in the squadron can get a glass to his mouth with one hand after one of these decoy patrols except Cal and he's got no nerve - he's made of cheese. But some nights we both have nightmares at the same time and Mac has to get up and find his teeth and quiet us. We don't sleep much at night. But we get tired and sleep all afternoon when there's nothing to do.

(9) John Raws, letter to a friend (20th July 1916)

The aeroplanes are wonderfully fascinating. One would like to watch them all day - theirs and ours, darting about the sky amid storms of shrapnel. They spot for the big guns, you know, and each side makes frantic efforts to drive hostile craft away when they come over. The sky is pitted with the little black and white shrapnel shells when any come in range of enemy guns. The shells are coming from all directions by the thousand, ours and theirs, but I'm resting in quite a comfy little machine gun emplacement. We hope to be out of it in a few days, thank goodness. Our losses have been heavy.