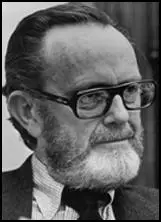

Philip Hart

Philip Hart was born in Bryn Mawr, Montgomery County, on 10th December, 1912. He was admitted to the Michigan bar after graduating from Michigan Law School in 1937.

Hart worked as a lawyer in Detroit until serving in the United States Army during the Second World War. He was wounded during the D-Day landings in Normandy and left the army in 1946 as a lieutenant colonel.

In 1949 Hart was appointed as Michigan Corporation Securities Commissioner. This was followed by other posts such as State Director of the Office of Price Stabilization (1951-52), District Attorney of the Eastern Michigan District (1952-53), legal adviser to the Governor of Michigan (1953-54) and Lieutenant Governor (1955-58).

A member of the Democratic Party, Hart was elected to the Senate in 1958. Over the next few years he gained the reputation for being a strong supporter of civil rights, anti-trust legislation and consumer and environmental protection. He took great pride in the fact that he was a leader in the Senate fight for the 1965 Voting Rights Act. As a result of his political activities he became known as the "Conscience of the Senate".

In 1975, Frank Church became the chairman of the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities. Members of this committee included Hart (Michigan), Gary Hart (Colorado), Walter Mondale (Minnesota), Richard Schweiker (Pennsylvania), Howard Baker (Tennessee) and Barry Goldwater (Arizona). This committee investigated alleged abuses of power by the Central Intelligence Agency and the Federal Bureau of Intelligence.

The committee looked at the case of Fred Hampton and discovered that William O'Neal, Hampton's bodyguard, was a FBI agent-provocateur who, days before the raid, had delivered an apartment floor-plan to the Bureau with an "X" marking Hampton's bed. Ballistic evidence showed that most bullets during the raid were aimed at Hampton's bedroom.

Church's committee also discovered that the Central Intelligence Agency and Federal Bureau of Investigation had sent anonymous letters attacking the political beliefs of targets in order to induce their employers to fire them. Similar letters were sent to spouses in an effort to destroy marriages. The committee also documented criminal break-ins, the theft of membership lists and misinformation campaigns aimed at provoking violent attacks against targeted individuals.

One of those people targeted was Martin Luther King. The FBI mailed King a tape recording made from microphones hidden in hotel rooms. The tape was accompanied by a note suggesting that the recording would be released to the public unless King committed suicide.

In September, 1975, a sub-committee made up of Gary Hart and Richard Schweiker was asked to review the performance of the intelligence agencies in the original John F. Kennedy assassination investigation. Hart and Schweiker became very concerned about what they found. On 1st May, 1976, Hart said: "I don't think you can see the things I have seen and sit on it."

When the Final Report of the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations was published in 1976, Hart joined Walter Mondale and Gary Hart to publish an appendix to the report. The three men pointed out that "important portions of the Report had been excised or security grounds". However, they believed that the CIA had "used the classification stamp not for security, but to censor material that would be embarrassing, inconvenient, or likely to provoke an adverse public reaction to CIA activities."

The appendix went on to say: "Some of the so-called security objections of the CIA were so outlandish they were dismissed out of hand. The CIA wanted to delete reference to the Bay of Pigs as a paramilitary operation, they wanted to eliminate any reference to CIA activities in Laos, and they wanted the Committee to excise testimony given in public before the television cameras. But on other more complex issues, the Committee's necessary and proper concern for caution enabled the CIA to use the clearance process to alter the Report to the point where some of its most important implications are either lost, or obscured in vague language."

Philip Hart died of cancer on 26th December, 1976. In a tribute to his distinguished career, Edward Kennedy suggested that the new Senate building be named after Hart. A bill sponsored by 85 senators passed, and the new structure became the Phil A. Hart Senate Office Building.

Primary Sources

(1) Philip Hart, Walter Mondale and Gary Hart, Final Report of the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations (1976)

We fully support the analysis, findings, and recommendations of this Report. If implemented, the recommendations will go far toward providing our nation with an intelligence community that is more effective in protecting this country, more accountable to the American public, and more responsive to our Constitution and our laws. The key to effective implementation of these recommendations is a new intelligence oversight committee with legislative authority.

Committees of Congress have only two sources of power: control over the purse and public disclosure. The Select Committee had no authority of any kind over the purse strings of the intelligence community, only the power of disclosure. The preparation of this volume of the Final Report was a case study in the shortcomings of disclosure as the sole instrument of oversight. Our experience as a Committee graphically demonstrates why legislative authority-in particular the power to authorize appropriations-is essential if a new oversight committee is to handle classified intelligence matters securely and effectively.

In preparing the Report, the Select Committee bent over backwards to ensure that there were no intelligence sources, methods, or other classified material in the text. As a result, important portions of the Report have been excised or significantly abridged. In some cases the changes were clearly justified on security grounds. But in other cases, the CIA, in our view, used the classification stamp not for security, but to censor material that would be embarrassing, inconvenient, or likely to provoke an adverse public reaction to CIA activities.

Some of the so-called security objections of the CIA were so outlandish they were dismissed out of hand. The CIA wanted to delete reference to the Bay of Pigs as a paramilitary operation, they wanted to eliminate any reference to CIA activities in Laos, and they wanted the Committee to excise testimony given in public before the television cameras. But on other more complex issues, the Committee's necessary and proper concern for caution enabled the CIA to use the clearance process to alter the Report to the point where some of its most important implications are either lost, or obscured in vague language. We shall abide by the Committee's agreement on the facts which are to remain classified. We did what we had to do under the circumstances and the full texts are available to the Senate in classified form. Within those limits, however, we believe it is important to point out those areas in the Final Report which no longer fully reflect the work of the Committee.

For example:

(1) Because of editing for classification reasons, the italicized passages in the Findings and Recommendations obscure the JVO significant policy issues involved. The discussion of the role of U.S. academics in the CIA's clandestine activities has been so diluted that its scope and impact on the American academic institutions is no longer clear. The description of the CIA's clandestine activities within the United States, as well as the extent to which CIA uses its ostensibly overt Domestic Contact Division for such activities, has been modified to the point where the Committee's concern about the CIA's blurring of the line between overt and covert, foreign and domestic activities, has been lost.

(2) Important sections which deal with the problems of "cover" were eliminated. They made clear that for many years the CIA has known and been concerned about its poor cover abroad, and that the Agency's cover problems are not the result of recent congressional investigations of intelligence activities. The deletion of one important passage makes it impossible to explain why unwitting Senate collaboration may be necessary to make effective certain aspects of clandestine activities.

(3) The CIA insisted upon eliminating the actual name of the Vietnamese institute mentioned on page 454, thereby suppressing the extent to which the CIA was able to use that organization to manipulate public and congressional opinion in the United States to support the Viet Nam War.

(4) Although the Committee recommends a much higher standard for undertaking covert actions and a tighter control system, we are unable to report the facts from our indepth covert action case studies in depth which paint a picture of the high political costs and generally meager benefits of covert programs. The final cost of these secret operations is the inability of the American people to debate and decide on the future scope of covert action in a fully informed way.

The fact that the Committee cannot present its complete case to the public on these specific policy issues illustrates the dilemma secrecy poses for our democratic system of checks and balances. If the Select Committee, after due consideration, decided to disclose more information on these issues by itself, the ensuing public debate might well focus on that disclosure rather than on the Committee's recommendations. If the Select Committee asked the full Senate to endorse such disclosure, we would be unfairly asking our colleagues to make judgments on matters unfamiliar to them and which are the Committee's responsibility.

In the field of intelligence, secrecy has eroded the system of checks and balances on which our Constitutional government rests. In our view, the only way this system can be restored is by creating a legislative intelligence oversight committee with the power to authorize appropriations. The experience of this Committee has been that such authority is crucial if the new committee is to be able to find out what the intelligence agencies are doing, and to take action to stop things when necessary without public disclosure. It is the only way to protect legitimate intelligence secrets, yet effectively represent the public and the Congress in intelligence decisions affecting America's international reputation and basic values. A legislative oversight committee with the power to authorize appropriations for intelligence is essential if America is to govern its intelligence agencies with the system of checks and balances mandated by the Constitution.