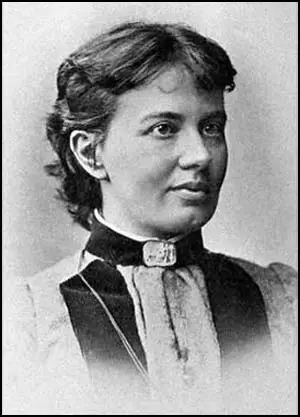

Sophia Kovalevskaya

Sophia Kovalevskaya, the daughter of General Vasily Korvin-Krukovsky, was born in Moscow on 15th January, 1850. Sophia was raised on the family estate at Palibino, near Vitebsk, with her sister, Anna Korvin-Krukovskaya. Her mother, Yelizaveta Fedorovna Schubert, held progressive views and made sure her two daughters received a good education. Sophia later recalled: "What a happy time that was! We were so enthusiastic about the new ideas, so sure that the present social state could not continue for long. We pictured to ourselves the glorious period of liberty and universal enlightenment of which we dreamt, and in which we firmly believed." The sisters were especially influenced by the Russian writers, Nikolai Chernyshevsky and Peter Lavrov.

Sophia and Anna felt that life was passing them by. Sophia argued in her unpublished memoirs: "People lived quietly and peacefully in Bilibino. They grew up, they grew old; they argued sometimes about some article in a journal, quite convinced that these questions belonged to another world, far apart from theirs, which would never have any contact with it. And then suddenly, wherever you looked, there appeared the signs of some strange madness, which unquestionably approached closer and closer and threatened to submerge this patriarchal way of life. In this period, from the sixties to the seventies, all intelligent sections of Russian society were concerned with one problem, the family antagonism between the young and the old."

General Vasily Korvin-Krukovsky was interested in mathematics and decided to paper the walls of the nursery with mathematical calculations. By the age of six Sophia began inventing mathematical problems and her mother decided to hire a young tutor, A. N. Strannoliubskii, to develop these abilities. Sophia later explained: "The meaning of these concepts I naturally could not yet grasp, but they acted on my imagination, instilling in me a reverence for mathematics as an exalted and mysterious science which opens up to its initiates a new world of wonders, inaccessible to ordinary mortals." However, when she suggested to her father that she would like to study the subject at university. He refused claiming that to go to university was "unbecoming for a woman".

Sophia's older sister, Anna Korvin-Krukovskaya wanted to study medicine at university. Her father also refused permission to leave the family home. At this time in Russia women could not live apart from their families without the written permission of their father or husband. Her only way to go to university was to find a husband who had progressive ideas on education. She approached Vladimir Kovalevsky, a young man whose family owned a publishing company. Anna asked him if he would marry her in order that she could study in Germany. He refused Anna but said he was willing to marry Sophia instead. As she was only seventeen years old at the time, she was unable to marry without her father's permission. Sophia decided to elope with Kovalevsky and they married in Germany in 1867.

Anna moved to Geneva, Switzerland, to study medicine. In 1867 she married fellow medical student, Victor Jaclard. The couple were deeply influenced by the anarchist views of Mikhail Bakuninand Sergi Nechayev. In their book Catechism of a Revolutionist (1869), they argued: "The Revolutionist is a doomed man. He has no private interests, no affairs, sentiments, ties, property nor even a name of his own. His entire being is devoured by one purpose, one thought, one passion - the revolution. Heart and soul, not merely by word but by deed, he has severed every link with the social order and with the entire civilized world; with the laws, good manners, conventions, and morality of that world. He is its merciless enemy and continues to inhabit it with only one purpose - to destroy it."

In 1869, Kovalevskaya began attending the University of Heidelberg, which allowed her to audit classes as long as the professors involved gave their approval. Sophia wrote to her friend about her plans: "I prepare for my examinations and write my thesis. Then I study independently. Later we (Sophia, Anna and Vladimir) will form a colony in Siberia. Anna writes a wonderful book while I make a discovery. Then we open a mixed secondary school. I have my own physics laboratory, drop medicine and take up physics and maths, applied to political economy and statistics." While in Heidelberg she met other women who had been forced to leave Russia to get a decent education. This included Anna Evreinova, who later became Russia's first woman lawyer and Natalya Armfeldt, a pioneer of the Sunday School Movement in Russia.

Sophia Kovalevskaya remained interested in politics. Her older sister joined the International Workingmen's Association, and became friends with its leader, Karl Marx. After the fall of Napoléon III in 1870 Anna and her husband returned to France. Anna participated in the Paris Commune of 1871. She was active in organising the food supply of the besieged city of Paris and co-founded and wrote for the journal La Sociale. Anna also collaborated closely with other revolutionaries in the conflict who favoured women's rights, including Louise Michel, Victoire Léodile Béra, Nathalie Lemel, Adèle Paulina Mekarska and Elisaveta Dimitrieva. Together they founded the Women's Union, which fought for equal wages for women, female suffrage, measures against domestic violence and the closing of the legal brothels in the city. Anna held strong views on drinking alcohol and urged that "drunkards who have lost all self-respect should be arrested". She also tried to get smoking banned in concerts.

Anna Korvin-Krukovskaya was disappointed by the lack of support women received from male colleagues in providing health services. Victor Jaclard urged their acceptance: "The women who had the courage to force open the doors of science will surely not fail to serve humanity and the Revolution." Victoire Léodile Béra also joined the debate and called for a move towards "that responsible alliance of men and women, that unity of feelings and ideas which alone can create, in honour, equality and peace."

When the Paris Commune was overthrown Anna and her husband were captured. He was sentenced to death, she, to hard labour in perpetuity in a penal colony in New Caledonia. However, in October 1871, the Jaclards managed to escape from prison with help from Sophia and her husband, Vladimir Kovalevsky.

At the University of Heidelberg Sophia studied under Hermann von Helmholtz, Gustav Kirchhoff and Robert Bunsen. Afterwards she moved to Berlin, where she taught by Karl Weierstrass. In 1874 she presented three papers - on partial differential equations, on the dynamics of Saturn's rings and on elliptic integrals - to the University of Göttingen as her doctoral dissertation. With the support of Weierstrass, this earned her a doctorate in mathematics summa cum laude. She thereby became the first woman in Europe to hold that degree.

Sophia Kovalevskaya wanted to be university lecturer in mathematics but was not allowed to because she was a woman. Universities also rejected her offer to provide lectures free of charge. Frustrated by her attempts to obtain an academic career she wrote to her husband: "You are quite right in saying that not a single woman has achieved anything as yet. But this makes it all the more imperative for me, while I still have energy and a little money, to put myself in conditions which will enable me to prove whether or not I have the brain to achieve anything."

Instead of an academic career she helped her husband in his various business ventures. These usually ended in failure and they eventually returned to Russia with their young daughter (born in 1878). Sophia wanted to teach but this was denied to her because of her left-wing political views. The government even issued a secret decree to the press forbidding any mention of her name. Vladimir Kovalevsky was also unable to find work and in 1883 he committed suicide.

Sophia now moved to Sweden and eventually was appointed to a five year position as "Professor Extraordinarius" (Professor without Chair) at Stockholm University. Soon afterwards she met and fell in love with the actress, novelist, and playwright Anne-Charlotte Edgren-Leffler. It has been claimed that the two women had an "intimate romantic friendship". In 1888 she won the Prix Bordin of the French Academy of Science. The following year she was appointed Professor Ordinarius (Professorial Chair holder) at the university, the first woman to hold such a position at a northern European university.

Sophia Kovalevskaya died of influenza, aged forty-one, on 10th February, 1891.

Primary Sources

(1) Sophia Kovalevskaya, Childhood Memories (Moscow, 1960)

What a happy time that was! We were so enthusiastic about the new ideas, so sure that the present social state could not continue for long. We pictured to ourselves the glorious period of liberty and universal enlightenment of which we dreamt, and in which we firmly believed. Besides this we had the sense of true union and cooperation. When three or four of us met in a drawing room among older people where we had no right to advance our opinions, a tone, a glance, even a sigh was sufficient to show each other that we were one in thought and sympathy....

People lived quietly and peacefully in Bilibino. They grew up, they grew old; they argued sometimes about some article in a journal, quite convinced that these questions belonged to another world, far apart from theirs, which would never have any contact with it. And then suddenly, wherever you looked, there appeared the signs of some strange madness, which unquestionably approached closer and closer and threatened to submerge this patriarchal way of life. In this period, from the sixties to the seventies, all intelligent sections of Russian society were concerned with one problem, the family antagonism between the young and the old.

(2) Cathy Porter, Fathers and Daughters: Russian Women in Revolution (1976)

Sophia's own confused and naive political views make this attitude particularly incomprehensible. We get some idea of these sympathies from her novel Nigilistka (The Woman Nihilist), translated as Vera Barantsova, whose eponymous heroine was inspired by one of her friends involved in the second great show trial of young revolutionaries in 1877. Vera is a romantic Turgenevian heroine basking in provincial boredom. But by the late 1860s she is already aware that the tinkling of sleigh bells is more likely to announce the arrival of the local police chief than of a potential suitor. The novel is both politically and psychologically naive, but it does reflect honestly some of Sophia's own confusions. "We must solve the social problem," Vera says after she has arrived in the capital in search of some socially useful activity, "and after that we can attend to study. Why muddle our brains with talk about wages, credit, and all the rest of it, when oppression and inequality are so self-evident?" But Vera herself never becomes directly involved in any political action. She merely clings to a boundless capacity for self-sacrifice, and she ultimately finds her fulfilment in marrying, and thus saving from death the distinctly unattractive leader of the revolutionaries on trial. She departs ecstatically with him for Siberia, and the author talks vaguely of her "useful work" there. Sofya wrote the novel in 1880, when she was becoming increasingly exasperated by the lack of creative outlets within Russia. The work was an expression both of frustration and indomitable optimism. Vladimir's financial speculations were adding to the strain of their fraught marriage, and her only consolations were her small daughter and her literary work.