London and Brighton Railway

By the 1830s Brighton was the most popular seaside resort in Britain, with over 2,000 people a week visiting the town. After the success of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway, a group of businessmen decided to build a railway between the town and London.

The London & Brighton Railway Company was set up and Robert Stephenson was asked to advise on the best possible route. Six possible routes were initially proposed but eventually the choice was narrowed down to those of George Rennie and George Bidder. Rennie suggested a direct line between London and Brighton, whereas Bidder favoured a route that avoided steep gradients and tunnels. Stephenson eventually selected George Bidder's route, but the London & Brighton Railway Company decided to ignore this advice and opted for Rennie's much shorter route.

George Rennie's proposals also made more use of existing track and only involved the construction of 39 miles of new railway. However, Rennie's proposals did involve building four long tunnels at Merstham (2,180), Balcombe (800 yards), Haywards Heath (1,450 yards) and Clayton Hill (1,730 yards). This route also required the building of a viaduct across the Ouse valley near Ardingly.

In July 1837, Parliament gave permission for John Rennie's proposed railway. The London & Brighton Railway Company appointed John Rastrick as the line's chief engineer. Rastrick had been working on locomotives since 1814 and had been one of the three judges at the Rainhill Trials. Rastrick had also worked with George Stephenson on several projects, including the Liverpool & Manchester Railway and Grand Junction Railway. However, George, like his son Robert, believed that John Rennie's route was impracticable.

The building of the line started in July 1838. The directors of the London & Brighton Railway realised the importance of linking Brighton with the harbour at Shoreham and a branch railway to it was constructed at the same time as the main line.

In March 1841, the Ouse Viaduct was completed and is one of the most elegant examples of early railway architecture, with its 37 tall arches and the four pavilions at each end of the viaduct. There was also an impressive viaduct just outside of Brighton that crosses the London Road.

The three longest tunnels on the line, Merstham, Balcombe and Clayton, were whitewashed and lit by gas. Small gas-works were established by the tunnels for this purpose. The lighting of the tunnels was an attempt to reduce the fears of the passengers travelling on the line.

The coal-burning locomotives made it impossible to keep the whitewashed tunnels clean. The passage of the trains also constantly blew out the gas jets that lit the tunnel. The tunnels were also lined with corrugated-iron sheeting to avoid water falling on open third-class carriages.

The line between London and Brighton was completed in September 1841. Over 3,500 men and 570 horses were used to build the railway. It had taken three years to build at a total cost of £2,634,059 (£57,262 per mile).

The first train entered Brighton Railway Station on 21st September 1841. At first, the railway company concentrated on bringing the rich to the coast in first-class carriages. It was not long, however, before the company realised that by offering cheap third-class tickets, they could increase the numbers of people using their trains. In 1843 the London to Brighton Railway reduced the price of their third-class tickets to 3s. 6d. In the six months that followed this reduction in price, 360,000 people arrived in Brighton by train.

1846 the company amalgamated with the London & Croydon to form the London, Brighton & South Coast Railway.

Large numbers of people now moved to the town to provide these visitors with food and entertainment. Between 1841 and 1871 the population of Brighton increased from 46,661 to 90,011, making it the fastest growing town in Britain.

The most popular locomotive used on the line was the Jenny Lind, that had been designed by David Joy and built by E. B. Wilson Railway Foundry at Leeds in 1847. The Jenny Lind differed from contemporary locomotives in having inside bearings for the driving wheels, and outside framing and bearings for the leading and trailing wheels. The Jenny Lind was an immediate success and E. B. Wilson Railway Foundry was soon producing one of these locomotives per week for railway companies all over Britain.

Primary Sources

(1) William James was an early advocate of a railway in Brighton (1823)

In Brighton we need an engine railroad through Kent, Surrey, Sussex and Hampshire, to connect London with the ports of Shoreham, Chatham and Portsmouth.

(2) Robert Stephenson interviewed by a Parliamentary Committee about the London to Brighton line (25th March, 1836)

The view that I have taken all along in laying out railroads, has been rather to go around rather than to go over high ground. I believe the commercial prospects of the (George Bidder) route is greater than the direct route. I calculate that the timing of the (George Bidder) route would be two hours. The direct route would not be quicker as the more severe gradients involved would result in slower running.

(3) Joseph Locke, interviewed by a Parliamentary Committee about the London to Brighton line (26th April, 1836)

The (George Bidder) route is six miles longer than the direct route. Taking two-pence to be the average charge per mile to the traveller, this will impose on him a shilling extra charge.

(4) (4) The Brighton Herald (16th May, 1840)

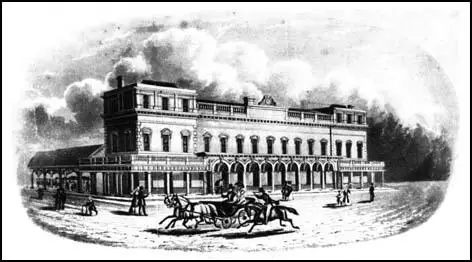

The entrance to the Brighton terminus is at the top of Trafalger Street where a very large space (bounded on the side nearest the town by a handsome wall) has been enclosed. The point is extremely central and when the approaches have been, as they must ultimately be, improved, it will be found that no better spot could have been selected. The distance from North Street through Surrey Street is but a two or three minutes walk.

(5) The Brighton Gazette (16th September, 1841)

The Brighton Terminus is a beautiful structure, and with the iron sheds in the rear, will not suffer from comparison with any railway terminus in existence. The offices and waiting rooms are most commodious, and are furnished with every convenience for passengers. Gas fittings for the whole terminus have been put up by Brighton and Hove General Gas Company.