Michael Deaver

Michael Keith Deaver was born in Bakersfield, California, on 11th April, 1938. After graduating from San Jose State University in 1960 he went into public relations and in the early 1970s worked for Ronald Reagan, when he was governor of California.

Deaver co-founded the public relations company, Deaver and Hannaford in 1975. The company "booked Reagan's public appearances, research and sell his radio program, and ghost-write his syndicated column." Peter Dale Scott claims that "all this was arranged with an eye to Reagan's presidential aspirations, which Deaver and Hannaford helped organize from the outset".

In 1977 Deaver and Hannaford registered with the Justice Department as foreign agents receiving $5,000 a month from the government of Taiwan. It also received $11,000 a month from a group called Amigos del Pais (Friends of the Country) in Guatemala. The head of Amigos del Pais was Roberto Alejos Arzu. He was the principal organizer of Guatemala's "Reagan for President" organization. Arzu was a CIA asset who in 1960 allowed his plantation to be used to train Cuban exiles for the Bay of Pigs invasion.

Peter Dale Scott has argued that Deaver began raising money for Ronald Reagan and his presidential campaign from some of his Guatemalan clients. This included Amigos del Pais. One BBC report estimated that this money amounted to around ten million dollars. Francisco Villgarán Kramer claimed that several members of this organization were "directly linked with organized terror".

Deaver and Hannaford also began to get work from military dictatorships that wanted to improve its image in Washington. According to Jonathan Marshall, Deaver was also connected to Mario Sandoval Alarcon and John K. Singlaub of the World Anti-Communist League (WACL). In the book, The Iran-Contra Connection (1987) he wrote: "The activities of Singlaub and Sandoval chiefly involved three WACL countries, Guatemala, Argentina, and Taiwan, that would later emerge as prominent backers of the contras.... these three countries shared one lobbying firm, that of Deaver and Hannaford."

In December, 1979, John K. Singlaub had a meeting with Guatemalan President Fernando Romeo Lucas García. According to someone who was at this meeting Singlaub told Garcia: "Mr. Reagan recognizes that a good deal of dirty work has to be done". On his return, Singlaub called for "sympathetic understanding of the death squads".

Another one of Deaver's clients was Argentina's military junta. A regime that had murdered up to 15,000 of its political opponents. Deaver arranged for José Alfredo Martinez de Hoz, the economy minister, to visit the United States. In one of Reagan's radio broadcasts, he claimed "that in the process of bringing stability to a terrorized nation of 25 million, a small number, were caught in the cross-fire, amongst them a few innocents".

Peter Dale Scott argues that funds from military dictatorships "helped pay for the Deaver and Hannaford offices, which became Reagan's initial campaign headquarters in Beverly Hills and his Washington office." This resulted in Ronald Reagan developing the catch-phrase: "No more Taiwans, no more Vietnams, no more betrayals." He also argued that if he was elected as president he "would re-establish official relations between the United States Government and Taiwan".

What Deaver's clients, Guatemala, Taiwan and Argentina wanted most of all were American armaments. Under President Jimmy Carter, arms sales to Taiwan had been reduced for diplomatic reasons, and had been completely cut off to Guatemala and Argentina because of human rights violations.

An article published in Time Magazine (8th September, 1980) claimed that Deaver was playing an important role in Reagan's campaign, whereas people like Campaign Director William J. Casey were outsiders have "valuable experience but exercise less influence over the candidate."

During the campaign Ronald Reagan was informed that Jimmy Carter was attempting to negotiate a deal with Iran to get the American hostages released. This was disastrous news for the Reagan campaign. If Carter got the hostages out before the election, the public perception of the man might change and he might be elected for a second-term. As Deaver later told the New York Times: "One of the things we had concluded early on was that a Reagan victory would be nearly impossible if the hostages were released before the election... There is no doubt in my mind that the euphoria of a hostage release would have rolled over the land like a tidal wave. Carter would have been a hero, and many of the complaints against him forgotten. He would have won."

According to Barbara Honegger, a researcher and policy analyst with the 1980 Reagan/Bush campaign, William J. Casey and other representatives of the Reagan presidential campaign made a deal at two sets of meetings in July and August at the Ritz Hotel in Madrid with Iranians to delay the release of Americans held hostage in Iran until after the November 1980 presidential elections. Reagan’s aides promised that they would get a better deal if they waited until Carter was defeated.

On 22nd September, 1980, Iraq invaded Iran. The Iranian government was now in desperate need of spare parts and equipment for its armed forces. Jimmy Carter proposed that the US would be willing to hand over supplies in return for the hostages.

Once again, the Central Intelligence Agency leaked this information to Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush. This attempted deal was also passed to the media. On 11th October, the Washington Post reported rumors of a “secret deal that would see the hostages released in exchange for the American made military spare parts Iran needs to continue its fight against Iraq”.

A couple of days before the election Barry Goldwater was reported as saying that he had information that “two air force C-5 transports were being loaded with spare parts for Iran”. This was not true. However, this publicity had made it impossible for Carter to do a deal. Ronald Reagan on the other hand, had promised the Iranian government that he would arrange for them to get all the arms they needed in exchange for the hostages. According to Mansur Rafizadeh, the former U.S. station chief of SAVAK, the Iranian secret police, CIA agents had persuaded Khomeini not to release the American hostages until Reagan was sworn in. In fact, they were released twenty minutes after his inaugural address.

Reagan appointed William J. Casey as director of the Central Intelligence Agency. In this position he was able to arrange the delivery of arms to Iran. These were delivered via Israel. By the end of 1982 all Regan’s promises to Iran had been made. With the deal completed, Iran was free to resort to acts of terrorism against the United States. In 1983, Iranian-backed terrorists blew up 241 marines in the CIA Middle-East headquarters.

After his election as president, Ronald Reagan, appointed Deaver as Deputy White House Chief of Staff under James Baker III. He took up his post in January 1981. Soon afterwards, Deaver's clients, Guatemala, Taiwan and Argentina, began to receive their payback. On 19th March, 1981, Reagan asked Congress to lift the embargo on arms sales to Argentina. General Roberto Viola, one of the junta members responsible for the death squads, was invited to Washington. In return, the Argentine government agreed to expand its support and training for the Contras. According to John Ranelagh (The Agency: The Rise and Decline of the CIA): "Aid and training were provided to the Contras through the Argentinean defence forces in exchange for other forms of aid from the U.S. to Argentina."

Reagan had more difficulty persuading Congress to provide arms to Guatemala. During a 4th May, 1981, session of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, it was announced that the Guatemalan death squads had murdered 76 leaders of the moderate Christian Democratic Party including its leader, Alberto Fuentes Mohr. As Peter Dale Scott pointed out in the Iran-Contra Connection: "When Congress balked at certifying that Guatemala was not violating human rights, the administration acted unilaterally, by simply taking the items Guatemala wanted off the restricted list."

Reagan and Deaver also helped Guatemala in other ways. Alejandro Dabat and Luis Lorenzano (Argentina: The Malvinas and the End of Military Rule) pointed out that the Ronald Reagan administration arranged for "the training of more than 200 Guatemalan officers in interrogation techniques (torture) and repressive methods".

Reagan's first Secretary of State, Alexander Haig, resigned on 25th June, 1982, as a result of the administration's foreign policy. He also complained that his attempts to help Britain in its conflict with Argentina over the Falkland Islands, was being undermined by Ambassador Jeane Kirkpatrick and some above her in the White House. In his book, Gambling With History: Ronald Reagan in the White House, Laurence I. Barrett argued that this person from the White House was Michael Deaver: "At an NSC session... Haig had observed Kirkpatrick passing Deaver a note. Concluding that Kirkpatrick was using Deaver to prime Reagan... Haig told Clark that a 'conspiracy' was afoot to outflank him."

Another of Deaver's clients, Taiwan, benefited from Reagan's support. Although George H. W. Bush promised China in August, 1982, that the United States would reduce its weapons sales to Taiwan, the reverse happened. Arms sales to Taiwan in fact increased to $530m in 1983 and $1,085 million in 1984.

Deaver officially worked primarily on media management. One of his great successes was the presentation of the Grenada invasion. As Sheldon Rampton and John Stauber pointed out in their book Toxic Sludge is Good For You (1995): "Following their (Michael Deaver and Craig Fuller) advice, Reagan ordered a complete press blackout surrounding the Grenada invasion. By the time reporters were allowed on the scene, soldiers were engaged in "mop-up" actions, and the American public was treated to an antiseptic military victory minus any scenes of killing, destruction or incompetence." Later, it was discovered that of the 18 American servicemen killed during the operation, 14 died in friendly fire or in accidents."

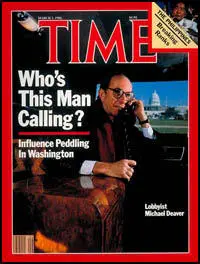

As well as Guatemala, Taiwan and Argentina, Deaver also worked closely with South Korea. He arranged for President Chun Doo Hwan to meet Reagan in the White House. It was Deaver's involvement with the Ambassador in Seoul, Richard L. Walker, a member of the World Anti-Communist League (WACL) that eventually led to his demise. Deaver resigned from the White House staff in May 1985 under investigation for corruption. It seems that Deaver had charged the Taiwan government $150,000 for arranging the meeting with Reagan. Deaver was eventually charged with perjury rather than violations of the 1978 Ethics in Government Act and was fined $100,000.

Books by Michael Deaver include Disarming Iraq: Monitoring Power and Resistance (2001) and Why I Am a Reagan Conservative (2005). He also helped Nancy Reagan write two books, A Different Drummer: My Thirty Years with Ronald Reagan (2001) and Nancy: A Portrait of My Years (2004).

Michael Deaver served as International Vice Chairman for Edelman Worldwide and manages public affairs programs for corporations such as United Parcel Services, Bacardi and Fujifilm. As Director of Corporate Affairs for Edelman's Washington office and provides strategic counsel to Nike, CSX, Nissan and Microsoft. He also oversaw United States based image problems for the governments of Portugal, India, and Chile.

Michael Deaver died of pancreatic cancer on 18th August, 2007 at his home in Bethesda, Maryland.

Primary Sources

(1) Peter Dale Scott, The Iran Contra Connection (1987)

Since their formation, the World Anti-Communist League (WACL) chapters have also provided a platform and legitimacy for surviving fractions of the Nazi Anti-Komintern and Eastern European (Ostpolitik) coalitions put together under Hitler in the 1930s and 1940s, and partly taken over after 1948 by the CIA's Office of Policy Coordination. In the late 1970s, as under Carter the United States pulled away from involvement with WACL countries and operations, the Nazi component of WACL became much more blatant as at least three European WACL chapters were taken over by former Nazi SS officers.

With such a background, WACL might seem like an odd choice for the Reagan White House, when in 1984 WACL Chairman John Singlaub began to report to NSC staffer Oliver North and CIA Director William Casey on his fund-raising activities for the contras. We shall see, however, that Singlaub's and WACL's input into the generation of Reagan's Central American policies and political alliances went back to at least 1978. The activities of Singlaub and Sandoval chiefly involved three WACL countries, Guatemala, Argentina, and Taiwan, that would later emerge as prominent backers of the contras. In 1980 these three countries shared one lobbying firm, that of Deaver and Hannaford, which for six years had supervised the campaign to make a successful presidential candidate out of a former movie actor, Ronald Reagan.

Still unacknowledged and unexplained is the role which funds from Michael Deaver's Guatemalan clients played in the 1980 Reagan campaign. Although contributions from foreign nationals are not permitted under U.S. electoral law, many observers have reported that rich Guatemalans boasted openly of their illegal gifts. Half a million dollars was said to have been raised at one meeting of Guatemalan businessmen, at the home of their President, Romeo Lucas Garcia. The meeting took place at about the time of the November 1979 visit of Deaver's clients to Washington, when some of them met with Ronald Reagan.

(2) Ronald Reagan, speech (August, 1979)

Today, Argentina is at peace, the terrorist threat nearly eliminated. Though Martinez de Hoz, in his U.S. talks, concentrates on economics, he does not shy from discussing human rights. He points out that in the process of bringing stability to a terrorized nation of 25 million, a small number were caught in the cross-fire, among them a few innocents... If you ask the average Argentine-in-the-street what he thinks about the state of his country's economy, chances are you'll find him pleased, not seething, about the way things are going.

(3) Robert Parry, Secrecy & Privilege (2004)

Like a Civil War victory at a major train junction, the election of Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush in 1980 put conservatives in control of key switching points in Washington for the transportation of ideas throughout the U.S. political system. By regaining the Executive Branch and winning the Senate, Republicans had their hands on many of the levers that could expedite the movement of favorable information to the American public and sidetrack news that might cause trouble.

Having learned how dangerous it was when critical scandals like Watergate or the CIA abuses started rolling down the tracks and building up steam, the conservatives took pains to keep hold of this advantage over what information sped through to the public and what didn't. Though often disparaged for being behind the times, conservatives - far better than liberals -grasped the strategic advantage that came with controlling these logistics of information. With the ability to rush public relations shock troops and media artillery to political battle fronts, conservatives recognized that they could alter the tactics and the strategies of what they called "the war of ideas."

Not losing any time, Republicans began devising new ways to manage, manufacture and deliver their message in the weeks and months after the Reagan-Bush victory. Some would call the concept "public diplomacy"; others would use the phrase "perception management." But the idea was to control how the public would perceive an issue, a person or an event. The concept was to define the political battlefield at key moments - especially when a story was just breaking - and thus enhance the chances of victory.

The Republican approach would be helped immeasurably by President Reagan's communication skills and by the image wizardry of White House aide Michael Deaver. But the administration's capability was given an important boost, too, by the intelligence backgrounds of two key figures, former campaign chief William Casey, who was named Reagan's CIA director, and Vice President George H. W. Bush, a former CIA director and a veteran of previous battles fought to contain political scandals. From their experiences in the intelligence fields, they understood what the CIA Old Boys, like Miles Copeland, meant when they talked about setting the "the spirit of the meeting" as a crucial element in managing political events.

(4) Peter Dale Scott, The Iran Contra Connection (1987)

The group that Deaver represented in Guatemala, the Amigos del Pais (Friends of the Country), is not known to have included Mario Sandoval Alarcon personally. But ten to fifteen of its members were accused by former Guatemalan Vice-President Villagran Kramer on the BBC of being "directly linked with organized terror." One such person, not named by Villagran, was the Texas lawyer John Trotter, the owner of the Coca-Cola bottling plant in Guatemala City. Coca-Cola agreed in 1980 to terminate Trotter's franchise, after the Atlantic Monthly reported that several workers and trade union leaders trying to organize his plant had been murdered by death squads.

One year earlier, in 1979, Trotter had traveled to Washington as part of a five-man public relations mission from the Amigos. At least two members of that mission, Roberto Alejos Arzu and Manuel F. Ayau, are known to have met Ronald Reagan. (Reagan later described Ayau as "one of the few people ...who understands what is going on down there.")

Roberto Alejos Arzu, the head of Deaver's Amigos and the principal organizer of Guatemala's "Reagan for President" bandwagon, was an old CIA contact; in 1960 his plantation had been used to train Cuban exiles for the Bay of Pigs invasion. Before the 1980 election Alejos complained that "most of the elements in the State Department are probably pro-Communist... Either Mr. Carter is a totally incapable president or he is definitely a pro-communist element."s (In 1954, Alejos' friend Sandoval had been one of the CIA's leading political proteges in its overthrow of Guatemala's President Arbenz.)

hen asked by the BBC how ten million dollars from Guatemala could have reached the Reagan campaign, Villagran named no names: "The only way that I can feel it would get there would be that some North American residing in Guatemala, living in Guatemala, would more or less be requesting money over there or accepting contributions and then transmitting them to his Republican Party as contributions of his own."

Trotter was the only U.S. businessman in Guatemala whom Alan Nairn could find in the list of Reagan donors disclosed to the Federal Election Commission. Others, who said specifically that they had contributed, were not so listed. Nairn heard from one businessman who had been solicited that "explicit Instructions were given repeatedly: Do not give to Mr. Reagan's campaign directly. Monies were instead to be directed to an undisclosed committee in California."

Trotter admitted in 1980 that he was actively fundraising in this period in Guatemala. The money he spoke of, half a million dollars, was however not directly for the Reagan campaign, but for a documentary film in support of Reagan's Latin American policies, being made by one of the groups supporting Reagan, the American Security Council (ASC). The film argued that the survival of the United States depended on defeat of the Sandinistas in Nicaragua: "Tomorrow: Honduras.. .Venezuela, the Dominican Republic, Mexico ...the United States."

Deaver's Amigos and Trotter were in extended contact with the ASC over this project. In December 1979, and again in 1980, the ASC sent retired Army General John Singlaub to meet Guatemalan President Lucas Garcia and other officials. According to one of Singlaub's 1979 contacts, the clear message was that "Mr. Reagan recognizes that a good deal of dirty work has to be done."" On his return to the United States, according to Pearce, Singlaub called for "sympathetic understanding of the death squads."" In 1980 Singlaub returned to Guatemala with another apologist for death squads, General Gordon Sumner of the Council for InterAmerican Security. Again the message to Lucas was that "help was on the way in the form of Ronald Reagan."

Jenny Pearce has noted that Singlaub's first ASC visit to Guatemalan President Lucas took place shortly after Lucas's meeting with Guatemalan businessmen, where he is "alleged to have raised half a million dollars in contributions to the [Reagan] campaign."

Since the 1984 Congressional cutoff of aid to the contras, Singlaub, as world chairman of the World Anti-Communist League, has been the most visible source of private support to the contras. He did this in liaison with both William Casey of the CIA and Col. Oliver North of the National Security Council staff."

But Singlaub's contacts with the World Anti-Communist League go back at least to 1980, when he was also purporting to speak abroad in the name of Reagan. Did the help from Reagan which Singlaub promised Guatemalans in 1980, like the "verbal agreements" which Sandoval referred to at Reagan's Inaugural, involve commitments even then from Reagan to that fledgling WACL project, the contras?

Mike Deaver should be asked that question, since in 1980 he was a registered foreign lobbyist for three of the contras most important WACL backers: Guatemala, Taiwan, and Argentina.

(5) Sheldon Rampton and John Stauber, Toxic Sludge is Good For You (1995)

Unlike the invasion of Normandy Beach during World War II, thee invasion of Grenada took place without the presence of journalists to observe the action. Reagan advisors Mike leaver and Craig Fuller had previously worked for the Hannaford Company, a PR firm which had represented the Guatemalan government to squelch negative publicity about Guatemala's massive violence against its civilian population. Following their advice, Reagan ordered a complete press blackout surrounding the Grenada invasion. By the time reporters were allowed on the scene, soldiers were engaged in "mop-up" actions, and the American public was treated to an antiseptic military victory minus any scenes of killing, destruction or incompetence. In fact, as former army intelligence officers Richard Gabriel and Paul Savage wrote a year later in the Boston Globe, "What really happened in Grenada was a case study in military incompetence and poor execution." Of the 18 American servicemen killed during the operation, 14 died in friendly fire or in accidents. To this day, no one has been able to offer a reliable estimate of the number of Grenadans killed. Retired Vice-Admiral Joseph Metcalf III remembered the Grenada invasion fondly as "a marvelous, sterile operation."

After reporters protested the news blackout, the government proposed creating a "National Media Pool." In future wars, a rotating group of regular Pentagon correspondents would be on call to depart at a moment's notice for US surprise military operations. In theory, the pool system was designed to keep journalists safe and to provide them with timely, inside access to military operations. In practice, it was a classic example of PR crisis management strategy enabling the military to take the initiative in controlling media coverage by channeling reporters' movements through Pentagon-designated sources.''

(6) Peter Dale Scott, The Iran Contra Connection (1987)

Distasteful as this Deaver-Hannaford apologetics for murder may seem today, the real issue goes far beyond rhetoric. Though Deaver and Hannaford's three international clients Guatemala, Taiwan, and Argentina-all badly wanted a better image in America, what they wanted even more urgently were American armaments. Under Carter arms sales and deliveries to Taiwan had been scaled back for diplomatic reasons, and cut off to Guatemala and Argentina because of human rights violations.

When Reagan became President, all three of Deaver's international clients, despite considerable opposition within the Administration, began to receive arms. This under-reported fact goes against the public image of Deaver as an open-minded pragmatist, marginal to the foreign policy disputes of the first Reagan administration, so that his pre-1981 lobbying activities had little bearing on foreign policy. The details suggest a different story.

Argentina could hardly have had a worse press in the United States then when Reagan took office. The revelations of Adolfo Perez Esquivel and of Jacobo Timmerman had been for some time front page news. This did not deter the new Administration from asking Congress to lift the embargo on arms sales to Argentina on March 19, 1981, less than two months after coming to office. General Roberto Viola, one of the junta members responsible for the death squads, was welcomed to Washington in the spring of 1981. Today he is serving a 17-year sentence for his role in the "dirty war."

Though the American public did not know it, the arrangements for U.S. aid to Argentina included a quid pro quo: Argentina would expand its support and training for the Contras, as there was as yet no authorization for the United States to do so directly. "Thus aid and training were provided to the Contras through the Argentinean defense forces in exchange for other forms of aid from the U.S. to Argentina .1128 Congressional investigators should determine whether the contemporary arms deals with Deaver's other clients, Guatemala and Taiwan, did not contain similar kickbacks for their contra proteges.

(7) Time Magazine (16th November, 1987)

Trans World Airlines is trying to fend off a takeover by Carl Icahn. The beleaguered company petitions the Transportation Department to hold a hearing that would delay Icahn's bid, but it looks like the request will be turned down. Searching for other options, TWA needs to buy time -- and influence. Enter former White House Deputy Chief of Staff Michael Deaver. That very month Deaver has left Ronald Reagan's employ to start a Washington "consulting" firm. According to Jon Ash, a former TWA executive, Deaver says, "I can give ((Transportation Secretary)) Elizabeth Dole a call." Deaver's fee: $250,000.

June 1985. Philip Morris wants to break into the closed South Korean cigarette market. Its competitor, R.J. Reynolds, has already hired Reagan's former National Security Adviser Richard Allen to press its case. Deaver tells Philip Morris that he has a close relationship with South Korean President Chun Doo Hwan, whose 1981 state visit to Washington he arranged. Deaver goes on to describe how he and Chun embraced in the Oval Office. His fee: $150,000. Deaver goes to Seoul, is treated like a dignitary, meets the President and other top leaders, and links the cigarette issue to pending trade matters. In addition, the company retains Michelle Laxalt, daughter of then Senator Paul Laxalt, a close friend of the President's.

Such tales of buying friends and influencing people were recounted at Deaver's perjury trial last week. He is charged with five counts of lying before a congressional committee and to federal grand jury investigators about his lobbying activities. Although former Government officials have been selling their access and influence for a long time, the Deaver trial provided a vivid look at how prevalent this practice has become.

None of these activities were necessarily illegal: Deaver was charged with perjury rather than violations of the 1978 Ethics in Government Act. But as Michael Kinsley of the "TRB" column in the New Republic notes, "Lobbying is an ideal illustration of TRB's Law of Scandal, which holds that the scandal isn't what's illegal; the scandal is what's legal." The practices revealed at the Deaver trial not only taint former officials who peddle their connections but also raise questions about the ethics of corporate America. Besides, they are often wasteful: TWA could not withstand the Icahn takeover bid.

(8) Angie C. Marek interviewed Michael Deaver for US News on 16th February, 2004.

Michael Deaver made his name as the image maker behind Ronald Reagan. Today, he counsels corporate clients on how to tailor their messages. As vice chairman of public relations firm Edelman, he recently oversaw a study of foreign attitudes toward U.S. business.

Q: What would be your advice to American companies working abroad today?

A: As Americans, I think we have to learn to listen to our audiences, especially as we move outside the United States. Companies have to have a local spokesman. And they need to be sensitive to cultural differences and realize that one message doesn't sell everywhere. Our survey shows that people are more drawn to media outlets unique to their country. Local is key.

Q: How much has Bush's foreign policy hurt our interests?

A: I think our foreign-policy decisions have a lot to do with the new attitudes in Europe. The Bush administration is the least trusted in Germany and France. It cuts both ways though: French and German foreign policy also affects American attitudes toward French wines and Hermes ties. When the government takes actions that have a negative impact on a business's products, the company simply must work harder to get its message across.

Q: Should firms distance themselves from the policies of their country?

A: I don't think they have to. McDonald's doesn't need to go on an antiwar campaign. The survey shows that above all else, the two things that are most important to consumers are the product offered and the service that comes with it.

Q: Will America's image rebound?

A: I think American companies will certainly weather this. Part of what the French and the Germans are listening to is their own leadership, and I think that leadership won't always stay as negative on the United States. The other thing to keep in mind is that French and Germans seem not to trust anything anymore. While Americans are becoming more confident in the future, Europeans are becoming more and more pessimistic.

(9) Douglas K. Daniel, Washington Post (20th August, 2007)

Deaver was celebrated and scorned as an expert at media manipulation for focusing on how the president looked as much as what the president said. Reagan's chief choreographer for public events, Deaver protected the commander in chief's image and enhanced it with a flair for choosing just the right settings, poses and camera angles.

"I've always said the only thing I did is light him well," Deaver told the Los Angeles Times in 2001. "My job was filling up the space around the head. I didn't make Ronald Reagan. Ronald Reagan made me."

Deaver's own image suffered a setback in 1987. He was convicted on three of five counts of perjury stemming from statements to a congressional subcommittee and a federal grand jury investigating his lobbying activities with administration officials.

Deaver blamed alcoholism for lapses in memory and judgment. He was sentenced to three years' probation and fined $100,000 as well as ordered to perform 1,500 hours of public service...

Deaver brought a public relations background and a long association with Reagan to his work as White House deputy chief of staff from 1981-1985. He and top Reagan advisers Edwin Meese III and James A. Baker III were known as "the troika" that, in effect, managed the presidency.

Deaver, however, was concerned more with Reagan's image than his policies. He also was responsible for the president's schedule and security and served as a liaison for any family matters.

To exert as much control as possible, Deaver steered the president away from reporters when he could, instead arranging Reagan in poses and settings that conveyed visually the message of the moment. Presidential news conferences were a rarity, which suited an actor-turned-politician who was at his best when using a script.

(10) Johanna Neuman and David Willman, Los Angeles Times (19th August, 2007)

"Deaver is curiously an underrated figure," Reagan biographer Lou Cannon said. "Lots of people can do backdrops. Deaver was one of the few advisors who Ronald Reagan emotionally cared about."

When the Iran-Contra scandal broke, embroiling the White House in controversy over trading arms to Iran to free American hostages, his close ties allowed Deaver to "talk truth to power," Cannon said. "Deaver was really blunt. He told Reagan he had to apologize." And whenever Reagan faced a major speech, Khachigian said, Deaver got the president "emotionally connected" to its themes.

Rice University historian Douglas Brinkley, who was with Deaver during his last public appearance, in May at the National Archives, said the combination of Deaver's eye for the visual and his relationship with Reagan made him a historic figure.

"He was exceedingly close to Ronald Reagan, almost an auxiliary member of family," Brinkley said. "That allowed Deaver as a salesperson to learn how to properly market him. He could intuit every wrinkle in Reagan's eyes, and he become one of the greatest crafters of stage designs for a president."

For his part, Deaver minimized his influence in the White House.

"The only thing I did is light him well," he often said.

In an interview with The Times in 2001, he added: "My job was filling up the space around the head. I didn't make Ronald Reagan. Ronald Reagan made me."

Early on, Deaver showed a knack for framing the politician's image.

One of his first jobs was working for California Republican George Murphy, a former actor, in his 1964 U.S. Senate campaign against Democrat Pierre Salinger, President Kennedy's former press secretary.

To present Salinger in his worst light, Deaver followed him to many a campaign stop, offering him a cigar as he stepped out of his car. Deaver later recalled that Salinger would stick the cigar in his mouth, giving photographers a ready shot of a fat cat -- hardly the man-of-the-people portrait a Democrat might prefer.

Deaver wrote in his 1988 memoir, "Behind the Scenes," that when he told Salinger the story 20 years later -- over lunch at Maxim's in Paris -- Salinger exclaimed, "You son of a bitch!"

During Reagan's 1980 presidential campaign, Deaver was forced out by campaign manager John Sears, along with staffers Jim Lake and Charles Black. Reagan was upset, writing in his memoir, "An American Life," that he told the remaining staff: "You've just driven away someone who's probably a better man than the three of you are."

For all the glory of his proximity to power, Deaver also suffered the ignominious fall that sometimes afflicts the influential. Leaving the Reagan White House after the first term, he set out to make the big money he had come to admire in so many of Reagan's wealthy friends -- the Walter Annenbergs, the William French Smiths, the Alfred S. Bloomingdales.

When he started his own consulting business, Deaver was able to make top dollar. So cocky was Deaver about his status as the Man Who Made Reagan that he posed for an infamous Time magazine cover in 1986. Sitting in the back seat of a limousine with a car phone pressed to his ear and the Capitol dome visible out the window, Deaver became the poster child for Time's story on influence peddling in Washington. In her memoir, "My Turn," Nancy Reagan said she warned him the cover was "a big mistake."

The cover caused a furor, reinforcing public suspicion about a revolving door between government service and get-rich consultancy. Deaver sought to stem the damage by calling for an independent counsel. Within a year, he had been convicted of three counts of perjury and sentenced to 1,500 hours of community service and a $100,000 fine. He insisted that he was innocent, that his faulty memory when answering questions stemmed from alcoholism; he had been drinking heavily in his last few months in government service. The son of recovering alcoholics entered a rehabilitation program in Maryland.