Cecil Stoughton

Cecil Stoughton was born on 18th January 1920. His parents separated when he was a child and he spent sometime in a boys' home in Omaha before rejoining his mother.

Stoughton studied singing at William Penn College in Oskaloosa before joining the United States Army during the Second World War. He was trained as a photographer and after the war he worked for the public information office. The head of the organization was Major General Chester Clifton.

In 1961 Clifton was appointed as a military aide to President John F. Kennedy. According to Richard B. Trask: "Captain Stoughton had so impressed John F. Kennedy with pictures of his inauguration that the new President, through his military aide, appointed him his official photographer." According to Stoughton: "Prior to JFK, we had Eisenhower, and there was no need for a photographer. He was about 63 years old and he didn't have the charm and charisma of President Kennedy and he didn't have a family that engaged the American public."

Amanda Hopkinson has argued that: "Stoughton handled colour well, but also shot in carefully contrasted black-and-white, which could be sent down the wires and transferred to the print media with rapid effect. He alternated his large-format Hasselblad portrait camera with a hand-held 35mm, which was more flexible when he accompanied the presidential retinue."

Barbara Baker Burrows, who worked for Life Magazine, has claimed: "As much as any, when these pictures were published around the world, they helped create the aura that later came to be called Camelot." It is estimated that Stoughton took over 8,000 photographs of the Kennedy family.

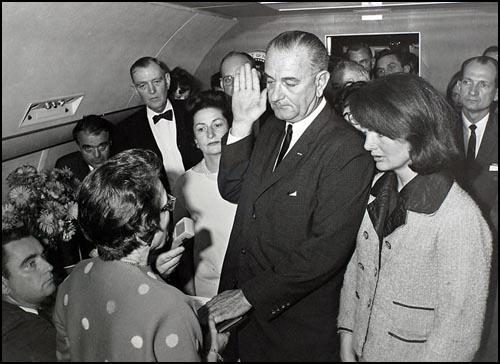

Stoughton was with John F. Kennedy when he was assassinated on 22nd November, 1963. Stoughton travelled back to Washington with Lyndon Baines Johnson and Jackie Kennedy on Air Force One and was asked to photograph the swearing-in of the new president.

Amanda Hopkinson has pointed out: "He (Stoughton) was the only photographer on board Air Force One, swiftly reloading to black-and-white film, then struck with horror as the shutter jammed. After much jiggling, he obtained 20 shots of the swearing-in ceremony, carefully cropped to cut out the bloodstains still showing on Jackie Kennedy's skirt and stockings. The one that achieved iconic status as it was immediately relayed around the world shows the line-up inside the crowded cabin. The official stands with her back to camera, holding out the Bible, facing Johnson, who has one hand on the book, the other raised to take the oath. On his right stands Lady Bird. On his left is Jackie, a wing of dark hair partially obscuring her eyes. Everyone in the picture looks serious, shocked and somehow too brightly dressed."

Stoughton continued to work for the White House until becoming head photographer to the National Park Service in 1967. He retired from the service in 1972. The following year he published The Memories - JFK, 1961-1963.

Cecil Stoughton died on 3rd November 2008.

Primary Sources

(1) Cecil Stoughton was interviewed by Bijal P. Trivedi for National Geographic Magazine (27th February, 2004)

Bijal P. Trivedi: How did you land a job as a photographer in the Kennedy White House?

Cecil Stoughton: I was working in the Public Information Office for the Army when my boss, Maj. Gen. Chester Clifton, was selected to be the military aide to President Kennedy.

At the inauguration day parade I took a picture of the President waving to all the remaining crewmembers standing on a model of PT-109.

Major General Clifton provided logistical support for the President and was present at all functions. He knew about my photographic abilities and told the President and Jackie that they would be in the public eye and needed someone in-house to capture various occasions and release the pictures to the press.

The advantage of an in-house photographer was that they could control me - if I did something wrong I would end up in Guam the next day!

Bijal P. Trivedi: Why did the media treat JFK differently from other Presidents?

Cecil Stoughton: Prior to JFK we had Eisenhower, and there was no need for a photographer. He was about 63 years old and he didn't have the charisma and charm of President Kennedy, and he didn't have a young family that engaged the American public. So the press were not as interested in photographing Eisenhower. Also the art of photography hadn't arrived yet—the press came with these big, bulky, cumbersome cameras that clicked twice and that was it.

(2) Richard B. Trask, American Heritage (November, 1988)

It was a typical motorcade. Cecil W. Stoughton had been in many like it. A forty-three-year-old veteran of the Signal Corps, Captain Stoughton had so impressed John F. Kennedy with pictures of his inauguration that the new President, through his military aide, appointed him his official photographer. In the course of thirty-four months, Stoughton had made more than eight thousand photographs of Kennedy and his family. Beginning on November 21, during the President’s much publicized autumn visit to shore up his political position in Texas, Stoughton recorded receptions at San Antonio, Brooks Medical Center, Kelly Field, and the Rice Hotel in Houston, and a testimonial dinner for Rep. Albert Thomas at the Houston Coliseum. The photographer mainly relied on two cameras: an Alpha Reflex and a 500 C Hasselblad. The Alpha was a 35-mm SLR, usually used with a wideangle 35-mm or a 180-mm telephoto lens. But Stoughton preferred the other camera. “The Hasselblad was my tool, an extension of my right arm. I used it every chance I got. It had interchangeable magazines. You would put black-and-white in one, color in one, transparency film in one.”

(3) Amanda Hopkinson, The Guardian (20th November, 2008)

Stoughton took more than 8,000 such images in the three-year period that ended so dramatically on November 22 1963. On that day, he was travelling in the presidential motorcade through Dallas. Once the shots were fired, he directed his driver to the Parkland hospital, where he waited outside the operating theatre for news. The answer came when he asked an official where Vice-President Johnson, being escorted from the hospital with Lady Bird, was going. The reply was unequivocal: "The president is going to Washington." The instant comeback was: "So am I."

He was the only photographer on board Air Force One, swiftly reloading to black-and-white film, then struck with horror as the shutter jammed. After much jiggling, he obtained 20 shots of the swearing-in ceremony, carefully cropped to cut out the bloodstains still showing on Jackie Kennedy's skirt and stockings. The one that achieved iconic status as it was immediately relayed around the world shows the line-up inside the crowded cabin. The official stands with her back to camera, holding out the Bible, facing Johnson, who has one hand on the book, the other raised to take the oath. On his right stands Lady Bird. On his left is Jackie, a wing of dark hair partially obscuring her eyes. Everyone in the picture looks serious, shocked and somehow too brightly dressed.

(4) Richard B. Trask, American Heritage (November, 1988)

President Johnson had decided to travel back to Washington on board Air Force One, with its more sophisticated communications system, rather than on Air Force Two. But he did not want to depart until he had taken the oath of office and until the deceased President and his widow were also aboard. Back at Parkland, the assistant press secretary Malcolm Kilduff made the public announcement of the death of President Kennedy at 1:33 P.M. A Dallas undertaker arrived at the hospital with a four-hundred-pound bronze casket into which the President’s body was placed. The casket left the hospital in an ambulance-hearse at about five minutes after two.

His own shock had kept Stoughton from taking photographs of the confused and devastated staff inside Parkland’s corridors. Aboard Air Force One, however, he saw the ambulance arriving, and from the forward port side of the Boeing 707 he made a series of ten shots with his 35mm Alpha, finishing off the black-and-white roll he had begun at Parkland’s emergency entrance.

The series of pictures begins with the ambulance’s arrival near the rear gangway of Air Force One. In the next grouping of photographs, Stoughton captures agents struggling to get the almost six-hundred-pound load up the narrow metal gangway. Many hands attempt to help with the burden, while on the tarmac below, the military aides Chester V. (“Ted”) Clifton, Jr., and Godfrey McHugh, Mrs. Kennedy, and members of the slain President’s inner circle watch with stricken faces. A uniformed Dallas police officer a few paces behind the melancholy gathering is seen in three subsequent frames, taking off his hat and holding it to his heart in a private salute until the casket is aboard. The last three frames in the sequence follow the former First Lady walking up the steps, forlorn and disheveled, with blood on her skirt and stockings. Behind follow Larry O’Brien, Ken O’Donnell, and Dave Powers.

Stoughton reloaded his Alpha with Tri-X film and put a roll of 120 black-and-white film in his Hasselblad; he wanted fast film if he was called upon to make pictures of the swearing-in. Kilduff confirmed that the President wanted to record the ceremony. About fifteen minutes after President Kennedy’s body was aboard, U.S. District Judge Sarah T. Hughes arrived to administer the oath. Stoughton suggested to Kilduff that they use the airplane Dictograph to record the swearing-in. The ceremony would take place in the stateroom, which had the largest open space in the cabin. The approximately sixteen-foot-square compartment, however, was still much too small to accommodate everyone on the plane comfortably. Stoughton stepped up onto a sofa and flattened himself against the rear bulkhead of the space in order to get the best view of the proceedings.

Stoughton’s cramped physical position was uncomfortable enough, but he also felt the greater strain of not wanting to muff the most important assignment of his career. When President Johnson asked Stoughton how he wanted them, the photographer replied, “I’ll put the judge so I’m looking over her shoulder, Mr. President.” Upon learning that Mrs. Kennedy would be present, he suggested that she should be on one side of the President with Mrs. Johnson on the other. Stoughton began his picture series, using his Alpha with available cabin light. The first six pictures show Johnson as the focal point with others awkwardly waiting.

Switching to his Hasselblad, Stoughton began to take another photo with his favorite camera, using an attached flash unit. “The first time I pushed the button, it didn’t work, and I almost died. I had a little connector that was loose because of all the bustling around, so I just pushed it in with my finger, and number two went off on schedule. I sprayed the cabin so I could get a picture of everybody there.” Prints of the first two Hasselblad photos cover a larger area than the 35-mm prints and are much clearer in detail. Unlike the 35-mm prints, these flash shots fill in the scene with light. Judge Hughes can be seen holding a Catholic missal (believed at the time to be a Bible) for the swearing-in ceremony and a sheet of paper with the oath of office typed out on it.

Moments after Stoughton’s eighth picture Mrs. Kennedy entered the compartment with O’Donnell. The former First Lady moved with O’Donnell and Powers nearby, to Johnson’s left side. Stoughton had already seen the bloodstains on Mrs. Kennedy’s skirt. He felt that photographing this in these historic pictures would be inappropriate, so he made sure the camera would not reveal them.

At 2:38 P.M. Judge Hughes administered the oath. Malcolm Kilduff held up the microphone while Stoughton quickly squeezed off four shots with the Hasselblad and four with the Alpha. Except for the words of Johnson and the judge, Stoughton realized that the only noise in the cabin was the clicking of his camera shutter.