Factory Food

Factory owners were responsible for providing their pauper apprentices with food. Sarah Carpenter was a child worker at Cressbrook Mill: "Our common food was oatcake. It was thick and coarse. This oatcake was put into cans. Boiled milk and water was poured into it. This was our breakfast and supper. Our dinner was potato pie with boiled bacon it, a bit here and a bit there, so thick with fat we could scarce eat it, though we were hungry enough to eat anything. Tea we never saw, nor butter. We had cheese and brown bread once a year. We were only allowed three meals a day though we got up at five in the morning and worked till nine at night."

In most textile mills the children had to eat their meals while still working. This meant that the food tended to get covered with the dust from the cloth. As Matthew Crabtree pointed out: "I began work at Cook's of Dewsbury when I was eight years old. We had to eat our food in the mill. It was frequently covered by flues from the wool; and in that case they had to be blown off with the mouth, and picked off with the fingers, before it could be eaten."

Abraham Whitehead was a cloth merchant from Holmfirth who joined the campaign for factory legislation. He told a parliamentary committee in 1832: "The youngest age at which children are employed is never under five, but some are employed between five and six, in woollen-mills, as piecers.... I have frequently seen them going to work between five and six in the morning.... They get their breakfast as they eat; they eat and work; there is generally a pot of water porridge, with a little treacle in it, placed at the end of the machine."John Birley complained about the quality of the food: "Our regular time was from five in the morning till nine or ten at night; and on Saturday, till eleven, and often twelve o'clock at night, and then we were sent to clean the machinery on the Sunday. No time was allowed for breakfast and no sitting for dinner and no time for tea. We went to the mill at five o'clock and worked till about eight or nine when they brought us our breakfast, which consisted of water-porridge, with oatcake in it and onions to flavour it. Dinner consisted of Derbyshire oatcakes cut into four pieces, and ranged into two stacks. One was buttered and the other treacled. By the side of the oatcake were cans of milk. We drank the milk and with the oatcake in our hand, we went back to work without sitting down."

Robert Blincoe argued that food in the mill was not as good as that he had been given in St. Pancras Workhouse:"The young strangers were conducted into a spacious room with long, narrow tables, and wooden benches. They were ordered to sit down at these tables - the boys and girls apart. The supper set before them consisted of milk-porridge, of a very blue complexion! The bread was partly made of rye, very black, and so soft, they could scarcely swallow it, as it stuck to their teeth... There was no cloth laid on the tables, to which the newcomers had been accustomed in the workhouse - no plates, nor knives, nor forks. At a signal given, the apprentices rushed to this door, and each, as he made way, received his portion, and withdrew to his place at the table. Blincoe was startled, seeing the boys pull out the fore-part of their shirts, and holding it up with both hands, received the hot boiled potatoes allotted for their supper. The girls, less indecently, held up their dirty, greasy aprons, that were saturated with grease and dirt, and having received their allowance, scampered off as hard as they could, to their respective places, where, with a keen appetite, each apprentice devoured her allowance, and seemed anxiously to look about for more. Next, the hungry crew ran to the tables of the newcomers, and voraciously devoured every crust of bread and every drop of porridge they had left."

Primary Sources

(1) John Birley was interviewed by The Ashton Chronicle on 19th May, 1849.

Our regular time was from five in the morning till nine or ten at night; and on Saturday, till eleven, and often twelve o'clock at night, and then we were sent to clean the machinery on the Sunday. No time was allowed for breakfast and no sitting for dinner and no time for tea. We went to the mill at five o'clock and worked till about eight or nine when they brought us our breakfast, which consisted of water-porridge, with oatcake in it and onions to flavour it. Dinner consisted of Derbyshire oatcakes cut into four pieces, and ranged into two stacks. One was buttered and the other treacled. By the side of the oatcake were cans of milk. We drank the milk and with the oatcake in our hand, we went back to work without sitting down.

(2) Matthew Crabtree was interviewed by Michael Sadler's Parliamentary Committee (18th May, 1832)

I began work at Cook's of Dewsbury when I was eight years old. We had to eat our food in the mill. It was frequently covered by flues from the wool; and in that case they had to be blown off with the mouth, and picked off with the fingers, before it could be eaten.

(3) Sarah Carpenter was interviewed by The Ashton Chronicle on 23rd June, 1849.

Our common food was oatcake. It was thick and coarse. This oatcake was put into cans. Boiled milk and water was poured into it. This was our breakfast and supper. Our dinner was potato pie with boiled bacon it, a bit here and a bit there, so thick with fat we could scarce eat it, though we were hungry enough to eat anything. Tea we never saw, nor butter. We had cheese and brown bread once a year. We were only allowed three meals a day though we got up at five in the morning and worked till nine at night.

(4) In his book, Robert Blincoe's Memoir (1828) John Brown recounts Blincoe's first experience of eating food in the factory apprentice house.

The young strangers were conducted into a spacious room with long, narrow tables, and wooden benches. They were ordered to sit down at these tables - the boys and girls apart. The supper set before them consisted of milk-porridge, of a very blue complexion! The bread was partly made of rye, very black, and so soft, they could scarcely swallow it, as it stuck to their teeth. Where is our roast beef and plum-pudding, he said to himself.

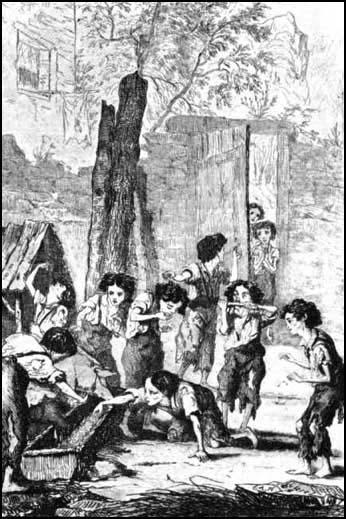

The apprentices from the mill arrived. The boys had nothing on but a shirt and trousers. Their coarse shirts were entirely open at the neck, and their hair looked as if a comb had seldom, if ever, been applied! The girls, like the boys, destitute of shoes and stockings. On their first entrance, some of the old apprentices took a view of the strangers; but the great bulk first looked for their supper, which consisted of new potatoes, distributed at a hatch door, that opened into the common room from the kitchen.

There was no cloth laid on the tables, to which the newcomers had been accustomed in the workhouse - no plates, nor knives, nor forks. At a signal given, the apprentices rushed to this door, and each, as he made way, received his portion, and withdrew to his place at the table. Blincoe was startled, seeing the boys pull out the fore-part of their shirts, and holding it up with both hands, received the hot boiled potatoes allotted for their supper. The girls, less indecently, held up their dirty, greasy aprons, that were saturated with grease and dirt, and having received their allowance, scampered off as hard as they could, to their respective places, where, with a keen appetite, each apprentice devoured her allowance, and seemed anxiously to look about for more. Next, the hungry crew ran to the tables of the newcomers, and voraciously devoured every crust of bread and every drop of porridge they had left.