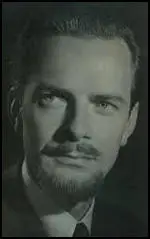

Frederic Mullally

Frederic Mullally was born in London on 25th February 1918. Mullally moved to India where he became a journalist. After working for The Statesman he returned to England and in 1944 was employed as political editor of The Tribune and as a sub-editor of The Reynolds News. In 1946 he became a columnist for The Sunday Pictorial.

Mullally married Suzanne Warner, an American who had been representing Howard Hughes in Britain. In 1950 they established the public relations firm of Mullally & Warner. Based in Mayfair its clients included Audrey Hepburn, Frank Sinatra, Douglas Fairbanks, Paul Getty, Frankie Laine, Vera Lynn, Yvonne De Carlo, Guy Mitchell, Sonja Henie, Line Renaud, Johnnie Ray and Jo Stafford.

Mullally became friendly with Stephen Ward. He introduced him to Joy Lewis, the wife of John Lewis. It was claimed that Mullally had once said that his greatest ambition was to sleep with all the beautiful women in London. Mullally eventually began an affair with Joy Lewis. Mullally later commented: "She (Joy) and Lewis had lots of fights, rows and walkouts. And on one occasion she went out in great distress, and didn't know what to do, and called Stephen Ward. And he put her up for the night at his place. It was a totally friendly gesture on his part." However, when Lewis heard about what happened, he became convinced that Ward was also having an affair with his wife.

Lewis also became angry with Ward over another relationship his wife had. Ward's friend, Warwick Charlton, has argued: "He (Lewis) went potty when he found Stephen had fixed her up with a Swedish beauty queen, a lesbian, with whom she had an affair. This he thought, was an assault on his manhood... He had a heart attack over it." Charlton was with Lewis when he heard the news of the affair. Lewis told Charlton "I will get Ward whatever happens". Lewis took out a revolver and said "I'll shoot myself, but not before I get Ward." Charlton claimed that "from then on, the most important thing in John's life was his burning hatred for Ward, which went on year after year."

The journalist, Logan Gourlay, remembers that in 1953 Lewis attempted to get his newspaper, The Daily Express, to publish an article discrediting Stephen Ward. Mullally explained: "Lewis got hold of an Express reporter, a young untrained boy, and gave him what purported to be an exclusive story that Stephen Ward and I were running a call-girl business in Mayfair." The editor, Arthur Christiansen, who was friendly with both Ward and Mullally, and refused to publish the story. Lewis now began to telephone the Marylebone Police Station anonymously, saying that Dr Ward was procuring girls for his wealthy patients. The police treated the calls as coming from a crank and ignored them.

In 1954 Lewis decided to divorce his wife. Lewis told Warwick Charlton that he was going to use the case to ruin Stephen Ward: "He's a bastard. Not only did he introduce Joy to Freddy Mullally but to some Swedish beauty queen as well. I'm going to cite seven men and one woman in my divorce case." The judge in the case noted it had "been fought with a consistent and virulent bitterness which could rarely have been excelled". The judge also questioned some of the evidence he heard. It was later claimed that "Lewis asked several witnesses to perjure themselves, and bribed some to do so."

Philip Knightley, the author of An Affair of State (1987), pointed out: "Mullally was part of Lewis's obsession too, perhaps with some justification - the divorce court judge found that he had had an affair with joy Lewis - and Lewis moved quickly to avenge himself. Lewis could be ruthless - he once ordered a racehorse he owned to be put down after it finished last in an important race - and his tactics to punish Ward and Mullally barred no holds. He began to gather evidence for his divorce case and let it be known that he planned to name both Ward and Mullally as co-respondents in the action. As a warm-up to the main bout, Lewis brought libel and slander actions against Mullally, claiming that Mullally had accused him in public of having paid £200 to a one-time employee of Mullally's to give false information in the divorce action. Lewis won. The court awarded him £700 damages and ordered Mullally to pay the costs, estimated at £1,000."

Mullally worked for The Picture Post between 1955 and 1956. His first novel, Dance Macabre (1958), was highly successful. This was followed by Man with Tin Trumpet (1961), The Assassins (1964), No Other Hunger (1966), The Prizewinner (1967), The Munich Involvement (1968), Clancy (1971), The Malta Conspiracy (1972), Venus Afflicted (1973), Hitler Has Won (1975), The Deadly Payoff (1976) and The Daughters (1988).

Primary Sources

(1) Philip Knightley, An Affair of State (1987)

Mullally was part of Lewis's obsession too, perhaps with some justification - the divorce court judge found that he had had an affair with joy Lewis - and Lewis moved quickly to avenge himself. Lewis could be ruthless - he once ordered a racehorse he owned to be put down after it finished last in an important race - and his tactics to punish Ward and Mullally barred no holds. He began to gather evidence for his divorce case and let it be known that he planned to name both Ward and Mullally as co-respondents in the action.

As a warm-up to the main bout, Lewis brought libel and slander actions against Mullally, claiming that Mullally had accused him in public of having paid £200 to a one-time employee of Mullally's to give false information in the divorce action. Lewis won. The court awarded him £700 damages and ordered Mullally to pay the costs, estimated at £1,000. Lewis won again in the divorce action, despite some curious sidelights to the case. (In one of these, another former employee of Mullally's gave a statement against him, then later retracted this evidence under oath and flew off to Canada. Lewis followed him there and persuaded him to revert to his original evidence. In another, a witness who gave evidence for Lewis had cosmetic surgery on her nose after the trial, the surgeon's bill being paid by Lewis.) Lewis was given custody of his daughter and Mullally was ordered to pay his own costs and one third of those of both John Lewis and his wife. These were estimated at £7,000 (£70,000 at today's values) and the total payout crushed Mullally financially.