Relationships in the First World War

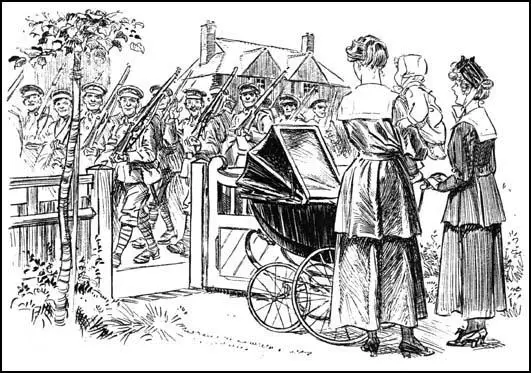

Mistress: "Which of them is your cousin?"

Nursemaid: (unguardedly): "I don't know yet, Ma'am.

Primary Sources

(1) Charles Hudson, journal entry, quoted in Soldier, Poet, Rebel (2007)

The conditions in the winter in Ypres salient were appalling. The water was too close to the surface to allow of deep trenches being dug, and this difficulty had been overcome to sonic extent by the building of ramparts of sandbags above ground level. The cold was intense but frost at least had the advantage of preventing one sinking as deeply into the mud at the bottom of the trench, as was normally the case. As time went slowly on, conditions improved with the increased production of trench boards and the issue of rubber thigh boots. Short rubber boots were a menace as they were always soaking wet. Amenities began to appear in the form of hot food containers, braziers and leather jerkins but only the young and strong could stand up to the conditions for long. Curiously enough my malaria had entirely left me and in spite of being cold and wet for days and nights on end I never had a day's sickness necessitating my being off duty throughout the rest of the war.

I am sure now that I did not appreciate the physical strain on men older than myself, nor did I allow for, or really sufficiently appreciate, the strain and anxiety of the married men. A sergeant in a confidential moment in a long night watch, once said to me, "It's all very well for you, you are unmarried and haven't a wife and children to worry about, but if I am killed what, I wonder, will happen to my family", My wife is not the managing sort, she has always depended entirely on me, and she has never been strong. Her people are dead and my mother is an invalid herself. After this I always tried surreptitiously to avoid sending married men on the more dangerous duties, but a high proportion of men, and nearly all the NCOs, were married.

Domestic anxiety was particularly acute amongst a considerable section of men who did not or could not trust their wives. As is well known now to everyone, but was not so well known to me then, relations or friends always get some obscure kick out of warning absent husbands that their wives are "carrying on". This type of thing was not by any means confined to the ranks. I had the greatest admiration for a certain RAMC colonel. Few of his rank visited companies in the front line, but he came round frequently, talked to the men, and really knew the conditions under which they lived. He was the commander of the Field Ambulance which normally dealt with our casualties and his visits were very much appreciated. I had been told that he had an appalling temper and treated his own officers very harshly, but he could not have been more charming to me. One day we read in the papers that he had been arrested for murder. When on leave he had shot his wife's lover whom he had found "in flagrante delicto". There was much talk in the company of a petition to be sent home from them on his behalf, but nothing came of this as, in fact, he was found to be mad and sent to Broadmoor. Later a lance corporal in my company, whom I knew from the censoring of his letters home had an unfaithful wife, was due for home leave. I had a talk with him, but the only result was that he refused to go home at all. The days of organised welfare had not yet begun.

Records that I still have show that we went out to France with twenty-eight officers and that in ten months twenty-six new officers had been posted to us. Many of the newly joined officers became casualties. The colonel, adjutant and second in command remained and about one officer per company. Not all the officers who had gone had been wounded or killed, many had gone sick, others were just too old or too nervous to stand up to the strain of the trenches. At 24 I found myself well up to, if not above, the average age of the officers.