John Monash

John Monash, the son of German parents, was born in Melbourne, Australia in 1865. After his education at Melbourne University he became a civil engineer. In 1887 Monash became an officer in the Australian Citizen Force.

On the outbreak of the First World War he was selected to command the 3rd Division of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) and in 1914 was sent to Gallipoli were he served with distinction.

In January 1916, Monash was promoted to the rank of major-general and sent to the Western Front. Working under General Sir Herbert Plumer, Monash developed a reputation as a careful and efficient commander. He took part in the offensives at Messines and Ypres, and in May 1918 replaced General William Birdwood as commander of the Australian Corps.

Monash was responsible for the planning of the highly successful Battle of Le Hamel. He led his troops with great skill and after the capture of Mont St Quentin and Peronne he was knighted in the field by George V (the first to receive this honour in over 200 years).

Monash is generally regarded as one of the most outstanding generals of the First World War and was also greatly respected because his tactics involved taking into account the survival of his own soldiers. This included what became known as peaceful penetration, a strategy that Monash used successfully at the Battle of Le Hamel.

In 1918 it was rumoured that the British prime minister, David Lloyd George was considering sacking Sir Douglas Haig as Commander-in-Chief and replacing him with Monash. However, Lloyd George was advised against this as Monash had only recently been promoted to the rank of lieutenant-general and was not a regular soldier. Sir John Monash, who returned to civilian life in Australia after the Armistice, died in 1931.

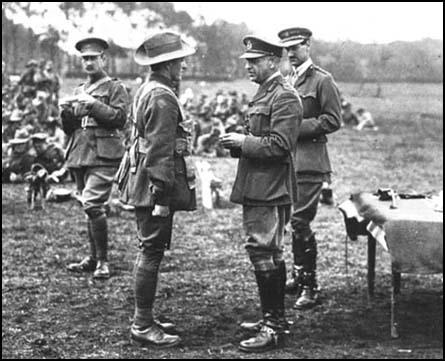

Australian Imperial Force after the Battle of Le Hamel in 1918.

Primary Sources

(1) General John Monash, letter (20th June 1916)

The question of getting hurt is in no sense a question of taking any special precautions. At Anzac the principal danger was from sharp-shooters, and one had to learn the dangerous spots and how to circumvent them. Shell-fire was of little danger only because it was so little in quantity, not because it did not reach every part of the area of one's perambulations. Here, there is practically no danger at all from rifle or machine-gun fire. The danger from artillery fire is

greater only because there is more of it, and one can say with definiteness that there is no spot within the area of one's daily movements which is really safe. It is merely a question of coincidence of a shell and oneself being simultaneously at one and the same spot. Experience has shown that it is quite futile to try and dodge shell-fire; one is just as likely to run into a beaten zone as out of it. There is no spot in the whole sector which may not, conceivably, be shelled.

(2) General John Monash, letter (11th January 1917)

The big question is, of course, the food and ammunition supply, the former term covering meat, bread, groceries, hay, straw, oats, wood, coal, paraffin and candles, the latter comprising cartridges, shells, shrapnel, bombs, grenades, flares, and rockets. It takes a couple of thousand men and horses with hundreds of wagons, and 118 huge motor lorries, to supply the daily wants of my population of 20 000.

With reference to food we also have to see that all the men in the front lines regularly get hot food - coffee, oxo, porridge, stews. They cannot cook it themselves, for at the least sign of the smoke of a fire the spot is instantly shelled. And they must get it regularly or they would perish of cold or frostbite, or get 'trench feet,' which occasionally means amputation.

The infantry offensive action consists of patrols, who creep right up to the enemy lines and bomb them, and in continual raids, one every two or three days, from fifty to three hundred men strong. We kill a good many Boches and bring back always a good deal of loot and sometimes a few prisoners. The other night Lieutenant Jewkes got five of them in a dugout calling 'Kamerad.' He came up to take their surrender, when one of them fired point-blank and hit him in the head. Jewkes has since died - so have the five Boches. They went a good many feet into the air when our gun-cotton sent them and dugout all up together.

(3) Philip Gibbs was a journalist who reported the war on the Western Front.

General Monash was another great general without professional training. He was an Australian Jew - tall, heavily built, big-nosed. It was to him, and to his acute brain and quick decision, that we owed the surprise attack by the Australians at Villers Bretonneux which saved Amiens, and perhaps the Channel ports, after the retreat of 1918, when disaster was very near and but little stood in the enemy's way that night.

Some years after the war I met General Monash at a luncheon in Guildhall. We came out together and I walked beside this tall hook-nosed man whose uniform was dangling with orders and decorations.

"Shall l fetch you a taxi-cab, sir?" I asked.

"No, my boy," he answered. "I shall go on the twopenny tube. I never waste money on taxis unless I can't help it."

(4) General John Monash, letter (18th March 1918)

As you know, our great problem is — how to keep our men fit and well. One way is to secure for them occasional rest and relief from their hardships by giving them leave to either London or Paris.

Although barracks and lodgings are provided both in London and Paris for Australian and Canadian soldiers to sleep in, at a nominal expense, yet such an arrangement does very little towards giving the boys what they really need when they go on leave. Moreover, owing to the serious food difficulties in England, we have been asked to discourage our men from going to London, but to send them either into the English provinces to the houses of private hosts, or to Paris. To a soldier who wants a change from his monotonous life at the front there is not much attraction in an English country place, where there are not theatres and no sight-seeing. So the leave given to Paris is much more eagerly sought by the Canadians and Australians.