Artillery : First World War

The word artillery was used to describe large-calibre mounted firearms. The calibre is the diameter of its barrel bore. In the 19th century artillery was divided into light and heavy, depending on the weight of solid shot fired. Light guns, deployed at battalion level, were usually 4-6 pounders, whereas heavy guns were 8-12 pounders.

At the beginning of the First World War the main support weapon for the British Army was the long-barrelled field gun. Also available was the QF (quick-firing) field gun that had a recoil system that bounced the barrel back into firing position.

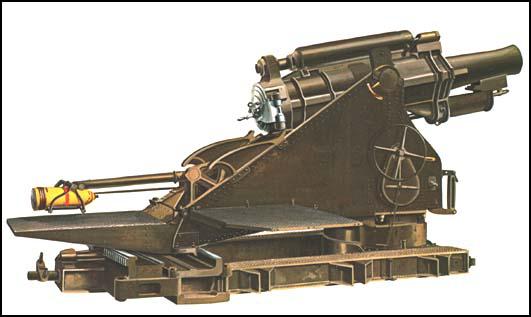

Howitzers were developed to be used under cover or against hidden targets. These fired heavy shells on a high trajectory through a short barrel and were the best type of artillery gun to employ against fortifications.

Another high-trajectory gun was the mortar. The projectile was dropped into its broad, stubby barrel and was fired by a pre-loaded explosive charge. By the end of the war some of these guns were capable of firing shells up to about 2km.

The stalemate caused by the trench system resulted in military commanders demanding long-range heavy field guns. Heavy howitzers (200-400mm) could fire shells weighing over 900kg over 18km. The British Army also asked for heavy guns that were light enough to be pulled across mud and shell-shattered ground.

Primary Sources

(1) Ernst Toller, I Was a German (1933)

My observation post was situated in a little pocket just under the peak of the hill. With the aid of glasses I could make out the French trenches and behind them the devastated town of Mousson and the Moselle winding its sluggish course through the early spring landscape. Gradually I became aware of details: a company of French soldiers was marching through the streets of the town. They broke formation, and went in single file along the communication trench leading to the front line. Another group followed them.

A subaltern was watching through his glasses.

"See those Frenchies" he asked.

"Yes, sir." "Let's tickle them up! Range twenty-two hundred," he cried to the telephonist.

And "Twenty-two hundred," echoed the telephonist.

I kept my eyes glued to the glasses. My head was in a whirl, and I was trembling with excitement, surrendered to the passion of the moment like a gambler, like a hunter. My hands shook and my heart pounded wildly. The air was filled with a sudden high-pitched whine, and a brown cloud of dust dimmed my field of vision.

The French soldiers scattered, rushed for shelter; but not all of them. Some lay dead or wounded.

"Direct hit!" cried the subaltern.

The telephonist cheered.

I cheered.