Alcohol and the First World War

The British government became concerned about the consumption of alcohol during the First World War. They feared that war production was being hampered by drunkenness. Other governments involved in the conflict were also worried about this problem. In August 1914 Tsar Nicholas II outlawed the production and sale of vodka. This involved the closing down of Russia's 400 state distilleries and 28,000 spirit shops. The measure was a complete failure, as people, unable to buy vodka, produced their own. The Russian government also suffered a 30% reduction in its tax revenue.

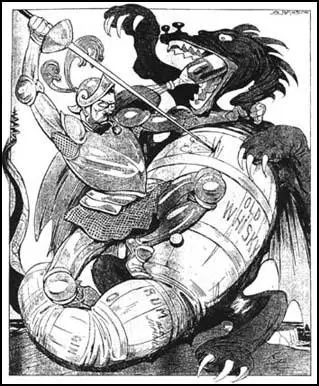

Attempts to reduce alcohol consumption were also made in Germany, Austria-Hungary, France and Italy. In Britain, David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, led the campaign against alcohol. He had been told by shipbuilders and heads of war factories, that men's wages had gone up so much that they could earn in two or three days what would keep them in drink for a week. A Newcastle shipbuilder complained that double overtime on Sunday meant no attendance on Monday." In January 1915, Lloyd George told the Shipbuilding Employers Federation that Britain was "fighting German's, Austrians and Drink, and as far as I can see the greatest of these foes is Drink."

Lloyd George started a campaign to persuade national figures to make a pledge that they would not drink alcohol during the war. In April 1915 King George V supported the campaign when he promised that no alcohol would be consumed in the Royal household until the war was over. Lord Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War and Richard Haldane, the Lord Chancellor, followed the king's example, but Herbert Asquith, who was a heavy drinker, refused to take the pledge. The National Review commented: "The failure of the Prime Minister to take the King's Pledge has naturally aroused comment." Asquith retorted angrily that Lloyd George had "completely lost his head on drink."

The government was particularly concerned about the amount of alcohol being consumed by female munition workers. A survey of four pubs in London revealed that in one hour on a Saturday night alcohol was consumed by 1,483 men and 1,946 women. Newspapers claimed that soldiers' wives were "drinking away their over-generous allowances". The Times reported that "we do not all realise the increase in drinking there has been among the mothers of the coming race, though we may yet find it a a circumstance darkly menacing to our civilisation".

In October 1915 the British government announced several measures they believed would reduce alcohol consumption. A "No Treating Order" laid down that any drink ordered was to be paid for by the person supplied. The maximum penalty for defying the Government order was six months' imprisonment. The Spectator gave its support to the legislation. It argued that it was the custom of the working-classes to buy drinks for "chance-met acquaintances, each of whom then had to stand a drink to everyone else" and believed that this measure would "free hundreds of thousands of men from an expensive and senseless social tyranny".

It was reported in The Morning Post on 14th March, 1916: "At Southampton yesterday Robert Andrew Smith was fined for treating his wife to a glass of wine in a local public-house. He said his wife gave him sixpence to pay for her drink. Mrs Smith was also fined £1 for consuming and Dorothy Brown, the barmaid, £5 for selling the intoxicant, contrary to the regulations of the Liquor Control Board."

Ernest Sackville Turner, in his book, Dear Old Blighty (1980) has pointed out: "In Newcastle police reported a licensee who, with his manager, had sought to evade punishment by causing a customer who had ordered eight drinks to consume all of them. As time passed the Order began to be flouted, to the relief of bar-room scroungers who had been having a thin time, but the police fought back. In Middlesbrough fines on innkeepers went as high as £40. The licensing authorities had powers to close public-houses which allowed treating and occasionally exercised them."

Public House opening times in cities and industrial areas were also reduced to 12.00 noon to 2.30 pm and 6.30 to 9.30 pm. Before the law was changed, public houses could open from 5 am in the morning to 12.30 pm at night. However, in most rural areas, people could continue to buy alcoholic drinks throughout the day.

The government also became concerned about the increase in alcohol consumption in certain areas. An enormous cordite munitions factory built to supply ammunition to British forces had been established in the small town of Gretna. Over 15,000 people, many of them from Ireland, had moved to the area to provide the work-force for the factory. They lived in neighbouring villages and spent much of their leisure time in the public-houses of Carlisle. Most of the workers were well-behaved but the drunkenness convictions quadrupled. Complaints were also received about "inappropriate sexual behaviour" in "snug" rooms in public-houses.

The government attempted to solve the problem by buying up the local breweries and 320 licensed premises. In Carlisle 48 out of 119 public-houses were shut down. The advertising of alcohol in the area was banned. So also was the selling of spirits on Saturdays. Salaried civil servants were brought in as managers of the public-houses with no inducement to push sales and ordered to install eating-rooms and to abolish "snugs". It was also prohibited to serve alcohol to people under the age of eighteen in the town.

The government also increased the level of tax on alcohol. In 1918 a bottle of whisky cost £1, five times what he had cost before the outbreak of war. This helped to reduce alcoholic consumption. Whereas Britain consumed 89 million gallons in 1914, this had fallen to 37 million in 1918. Convictions for drunkenness also fell dramatically during the war. In London in 1914, 67,103 people were found guilty of being drunk. In 1917 this had fallen to 16,567.

Primary Sources

(1) The Morning Post (14th March 1916)

At Southampton yesterday Robert Andrew Smith was fined for treating his wife to a glass of wine in a local public-house. He said his wife gave him sixpence to pay for her drink. Mrs Smith was also fined £1 for consuming and Dorothy Brown, the barmaid, £5 for selling the intoxicant, contrary to the regulations of the Liquor Control Board.

(2) Ernest Sackville Turner, Dear Old Blighty (1980)

In Newcastle police reported a licensee who, with his manager, had sought to evade punishment by causing a customer who had ordered eight drinks to consume all of them. As time passed the Order began to be flouted, to the relief of bar-room scroungers who had been having a thin time, but the police fought back. In Middlesbrough fines on innkeepers went as high as £40. The licensing authorities had powers to close public-houses which allowed treating and occasionally exercised them.

(3) Frank P. Crozier, A Brass Hat in No Man's Land (1930)

I had not long previously been forced to call the attention of a brigade commander of a formation with which I had cause to be remotely connected, from time to time, to a most extraordinary sight I had witnessed. To my amazement I saw a colonel sitting at the entrance to a communication trench, personally issuing unauthorised tots of rum to his men as they passed him in single file at 3 p.m., on a fine clear Spring-like afternoon, on their way to hold a line for the very first time. The brigadier did not seem to realise the gravity of the case. He did not appreciate the danger. The mentality of this colonel was all wrong. Badly based on brandy, he thought everybody else felt as he did - dejected and desolate. Despondent and at all times difficile, he was a victim of drugs and drink, and ultimately died. But, and here is the important point, because he had local pull, he had been entrusted with the care of youth for eighteen months. This was bad enough. The safety of the line was another matter. Seeing what I had seen, knowing what I knew and visualising the future, as his brigadier took no notice of my protest, even going so far as to say the matter was no business of mine, I determined on having the wretchedly miserable man removed, for the good of us all. I saw a very senior medical officer about the matter and persuaded him to take action, with the result that the drink-drug addict was removed to England, there to degenerate and eventually die. The safety of the line outweighed all other considerations. Drink control was imperative.