Peter Norman

Peter Norman was born in Melbourne, Australia, on 15th June, 1942 and grew up in a devout Salvation Army family. He joined the Melbourne Harriers and won his first major title, the Victoria junior 200m championship in 1960.

Norman became a physical training teacher. Norman continued to run and in 1966 he won the national championship. In the Commonwealth Games team in Jamaica he took bronze in the 220 yards and the 4 x 110 yard relay team.

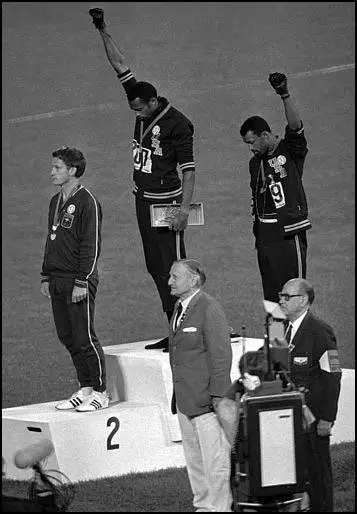

Norman finished second in the 1968 Olympic Games 200m final. Tommie Smith won gold in the 200m by setting a new world record. John Carlos, took bronze. While the Star-Spangled Banner played during the medal ceremony, Smith raised his right, black-gloved fist to represent Black Power, while Carlos's raised left fist represented black unity. Norman joined the protest by wearing an Olympic Project for Human Rights badge.

At a press conference after the event Tommie Smith said: "If I win I am an American, not a black American. But if I did something bad then they would say 'a Negro'. We are black and we are proud of being black. Black America will understand what we did tonight." Smith admitted he had raised his right fist to represent black power in America, while John Carlos raised his left fist to represent black unity.

The International Olympic Committee president, Avery Brundage, immediately suspended Tommie Smith and John Carlos from the U.S. team and banned from the Olympic Village. When they arrived home they received countless death threats. Australia's conservative media called for Peter Norman to be punished but Julius Patching, his team manager, refused to take action against him. Later Norman was to say: “It was like a pebble into the middle of a pond, and the ripples are still traveling.”

Peter Norman won the 200m gold medal at the Pacific Games held in Tokyo in 1969. However, he could only finish third at the Australian trials for the 1972 Munich Olympic Games. He continued running until 1985, when a tendon injury became infected, and gangrene set in. According to one report, he only avoided amputation because one doctor argued that "you can't cut off the leg of an Olympic silver medallist".

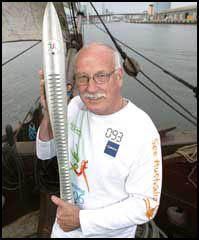

After his retirement from running he was active in athletics administration, Olympic fundraising and the organisation of major events like the 2000 Sydney Olympics. He also worked on a film with his nephew Matt Norman, Salute: The Peter Norman Story.

Peter Norman continued to suffer from bad health and underwent triple bypass surgery. He died as a result of a heart attack on 3rd October, 2006. Tommie Smith and John Carlos, were both pall-bearers at his funeral.

Primary Sources

(1) BBC Report (17th October, 1968)

Two black American athletes have made history at the Mexico Olympics by staging a silent protest against racial discrimination.

Tommie Smith and John Carlos, gold and bronze medallists in the 200m, stood with their heads bowed and a black-gloved hand raised as the American National Anthem played during the victory ceremony. The pair both wore black socks and no shoes and Smith wore a black scarf around his neck. They were demonstrating against continuing racial discrimination of black people in the United States.

As they left the podium at the end of the ceremony they were booed by many in the crowd.

At a press conference after the event Tommie Smith, who holds seven world records, said: "If I win I am an American, not a black American. But if I did something bad then they would say 'a Negro'. We are black and we are proud of being black. "Black America will understand what we did tonight." Smith said he had raised his right fist to represent black power in America, while Carlos raised his left fist to represent black unity. Together they formed an arch of unity and power. He said the black scarf represented black pride and the black socks with no shoes stood for black poverty in racist America. Within a couple of hours the actions of the two Americans were being condemned by the International Olympic Committee. A spokesperson for the organisation said it was "a deliberate and violent breach of the fundamental principles of the Olympic spirit." It is widely expected the two will be expelled from the Olympic village and sent back to the US.

In September last year Tommie Smith, a student at San Jose State university in California, told reporters that black members of the American Olympic team were considering a total boycott of the 1968 games.

He said: "It is very discouraging to be in a team with white athletes. On the track you are Tommie Smith, the fastest man in the world, but once you are in the dressing rooms you are nothing more than a dirty Negro." The boycott had been the idea of professor of sociology at San Jose State university, and friend of Tommie Smith, Harry Edwards. Professor Edwards set up the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR) and appealed to all black American athletes to boycott the games to demonstrate to the world that the civil rights movement in the US had not gone far enough. He told black Americans they should refuse "to be utilised as 'performing animals' in the games."

Although the boycott never materialised the OPHR gained much support from black athletes around the world.

(2) New York Times (4th October, 2005)

Peter Norman, the Australian sprinter who shared the medals podium with Tommie Smith and John Carlos while they gave their black power salutes at the 1968 Olympics, died Tuesday. He was 64.

The cause was a heart attack, said Danny Corcoran, chief executive of Athletics Australia.

Norman, a five-time national champion in the 200 meters, won the silver medal in the event at the Mexico City Games. Smith set a world record in winning the gold medal and Carlos took the bronze, and their civil rights protest became a flash point of the Olympics.

Smith and Carlos stood shoeless, each wearing a black glove on his raised, clenched fist. They bowed their heads while the national anthem played.

“It wasn’t about black or white,” Carlos said Tuesday. “It was just about humanity, faith in God and faith in making it a better world.”

Norman, a physical education teacher, stood on the front platform during the ceremony. He wore a human rights badge on his shirt in support of the two Americans and their statement against racial discrimination in the United States.

“It was like a pebble into the middle of a pond, and the ripples are still traveling,” Norman said last year.

Smith, Carlos and Norman drew criticism and threats for their actions, gestures that came in the aftermath that year of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

Carlos, now 61, said Norman faced his own struggles upon returning to Australia after the Olympics.

“We had our cross to bear here in the United States,” Carlos said. “Peter had a bigger cross to bear because he didn’t have anyone there to help shield him other than his family.”

(3) Mike Hurst, Courier-Mail (8th October, 2006)

Peter Norman, a wonderful man and a wonder of an athlete, reached the finish line this week, aged 64.

He will be remembered as the middleman, the little white bloke who split two giants of American sprinting, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, in the 200m final at the Olympic Games in Mexico in 1968.

He is also remembered for taking a supportive, although not overt, position in the so-called Black Power medal ceremony, in which Smith and Carlos mounted the dais in black socks. Heads bowed, each raised a black-gloved fist during the American anthem.

Smith and Carlos were thrown out of the athletes' village and became pariahs in US sporting life until at least the early 1980s, by which time the damage to their lives was irreparable.

In winning the silver medal, Norman clocked 20.06sec, still one of the oldest Australian records. Norman later said that when he began the race he was nervous he was about to run last in an Olympic final. But he put in a final spurt, edging Carlos out of second place by 0.04sec.

As Norman waited for the medal ceremony, he made it known he believed in the cause motivating the Movement For Human Rights Project that inspired the Olympic protest. Smith gave him a button he wore on his tracksuit jacket during the ceremony.

Carlos had forgotten his gloves and, at Norman's suggestion, each of the Americans wore one of Smith's gloves. The protest caused a worldwide uproar.

But Norman was protected by his team manager, Judy Patching, who, "with a smile, told me to consider myself severely reprimanded", Norman said. "Then she asked me how many tickets I wanted for the hockey."

For many years after 1968, Norman maintained contact with the men who shared the podium with him – more so with Smith, for whom he had a high regard.

I met Peter Norman in 1970. He became a friend. Consistent, good company on the rare occasions we managed to catch up; no airs and graces about him, no deceptions, always telling it as he saw it, always with good humour, always happy to have a beer and for him the glass was always half-full.

I bumped into him at the Sydney Olympics. He showed me the dreadful scar left by a golden staph infection he contracted in hospital in Melbourne when he had surgery on his achilles tendon. Half the soleus muscle was gone. All that was left, it seemed, was bone and tendon.

"It was a worry there for a while. I'm happy though. I'm still buying my shoes in pairs," he laughed.

Several weeks ago, out of the blue, I phoned him and he sounded frail. He'd just had a heart attack.

"I had felt pretty ordinary, a little upset during the night and decided to take myself down to the hospital in the morning," he told me.

"They ran some tests and the doctor said: 'You've had more than a little upset; you've had a major incident. We're going to run some more tests on you in the next six weeks or so'."

Norman checked into hospital a couple of weeks later and an angiogram operation went badly wrong, as these things can, when the wire cut off the corner of an artery valve.

He never did have much luck in hospitals. A couple of weeks later he said: "I went in for the angiogram and after that they put me back in and I ended up with triple bypass surgery. But I'm getting better. I've slowed up a bit, but I've already walked down to the supermarket to get the groceries."

Earlier this year he handed me an A4-size colour photograph of that Mexico medal ceremony protest. Smith, Carlos and Norman had all signed it. Norman, like Smith and Carlos, had signed it in gold ink.

Norman was born on June 15, 1942, in Thornbury, Melbourne, and grew up in a devout Salvation Army family.

By his own account, he grew up as a sports buff. He told in 2000 of how, during the 1956 Olympic Games in Melbourne, he wagged school to sell pies to spectators.

He gained inspiration from watching such events as Betty Cuthbert becoming the first Australian to win an Olympic gold medal on Australian soil. His customers, however, were sold cold pies.

Despite wagging school, Norman became a high school teacher, instructing in physical education. He did an apprenticeship as a butcher, a trade he kept as a sideline.

He was already making his mark in athletics, despite being an asthmatic and a slow starter. But he was blessed with a good coach and mentor, Neville Sillitoe, as well as natural ability.

He earned a crack at the 220-yard sprint at the 1962 Commonwealth Games in Perth. He came sixth in the semi-final. But he was back in the Commonwealth Games team to Jamaica in 1966, taking bronze in the 220 yards and running in the 4x110 yard relay team, which also came third.

That was the year he became Australian 200m champion, a title he kept in each of the five races up to 1970. Norman's time of athletic greatness thus went on past the 1968 Mexico Olympics. In 1970, he came fifth in the 200m at the Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh.

But his luck changed in 1985, when he went for a run and hurt his achilles tendon. Dreadfully painful complications dragged on for years.

Pressures took their toll and on September 17, 2004, Norman pleaded guilty to a fourth offence of exceeding the 0.05 drink-driving limit and also to a charge of unlicensed driving. The Sunshine Magistrates Court set a $500 fine and disqualified Norman from driving for 14 months.

Luckily, Norman's story was recorded on film before he died. Salute – The Peter Norman Story, produced by his nephew Matt Norman, opens in the US in February. Matt says his uncle cried with pleasure on seeing it.

He says the website salutethemovie.com had 800,000 hits in the 24 hours after Peter died. Some mourners have made donations, which will go to the rehabilitation of New Orleans. This, Matt says, is what the champion of civil rights and black Americans would have wanted.

Norman is survived by his second wife, Jan, and their daughters, Belinda and Emma, his first wife, Ruth, and children, Gary, Sandra and Janita, and four grandchildren.

(4) Michael Carlson, The Guardian (5th October, 2006) )

One of the most dramatic moments in Olympic history came in 1968 when Tommie Smith and John Carlos, the US 200-metre medallists in Mexico City, stood on the victory dais, barefoot, heads bowed and gloved fists raised during the playing of the Star-Spangled Banner. The third man in the photograph of this enduring symbol of protest against racial discrimination was Australia's Peter Norman, the silver medallist, who has died suddenly aged 64; he, too, became an icon of the American civil rights movement, if an unlikely one.

In the photo, he wears a badge identical to those worn by Smith and Carlos, identifying their Olympic Project for Human Rights. But Norman's participation was more than a token. "While he didn't raise a fist, he did lend a hand," was how Smith explained it.

The Americans discussed their plan with Norman, then a 26-year-old physical education teacher and Salvation Army officer, before the ceremony. When Carlos realised he had forgotten his black gloves, Norman suggested the two share Smith's pair. He then asked what he could do to support them, and Carlos managed to get an additional badge, which Norman attached to his track suit, over his heart. After the ceremony, Norman explained himself simply: "I believe that every man is born equal and should be treated that way."

Smith and Carlos were expelled from the games. Their competitive careers were shattered and their marriages crumbled under the strain. But the Australian team's chef de mission, Julius "Judy" Patching, resisted calls from the country's conservative media for Norman to be punished, telling the athlete in private, "They're screaming out for your blood, so consider yourself severely reprimanded. Now, you got any tickets for the hockey today?" Patching seemed mystified as to what the fuss was about, though he did warn the athlete to be careful.