John Carlos

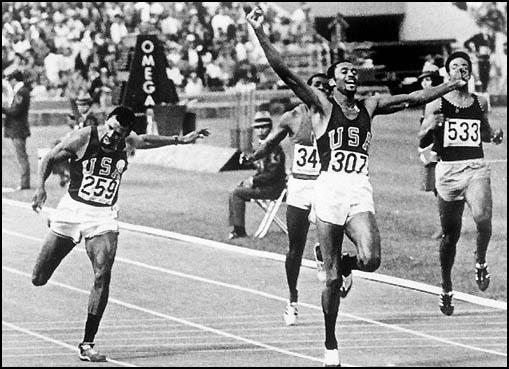

John Carlos was born in Harlem, New York on 5th June, 1945. A talented athlete he won a scholarship to East Texas State University. Later he moved to San Jose State College. In 1967 he won the gold medal at 200 meters at the Pan-American Games. In the 1968 Olympic Trials, John Carlos broke the world record when he beat Tommie Smith in the 200 meter finals.

In 1967, John Carlos became a founding member of the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR). Harry Edwards, a sociology professor at San Jose State College, tried to persuade African American athletes to boycott the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City to draw attention to racism in the United States. This campaign failed but some athletes did agree to wear black knee-length socks, while competing in their events.

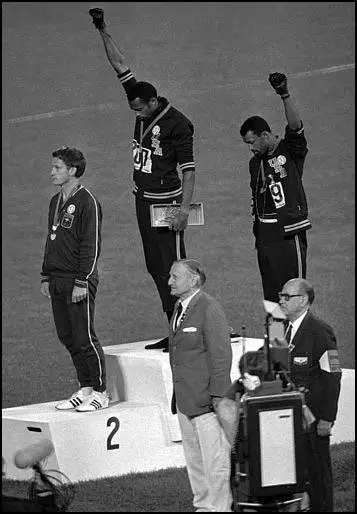

Tommie Smith won the gold in the 200m final of the 1968 Olympic Games by setting a new world record. John Carlos, took the bronze. Both men decided to make a protest. While the Star-Spangled Banner played during the medal ceremony, Smith raised his right, black-gloved fist to represent Black Power, while Carlos's raised left fist represented black unity. Peter Norman, the Australian athlete who won the silver medal, joined the protest by wearing an Olympic Project for Human Rights badge.

At a press conference after the event Tommie Smith said: "If I win I am an American, not a black American. But if I did something bad then they would say 'a Negro'. We are black and we are proud of being black. Black America will understand what we did tonight." Smith admitted he had raised his right fist to represent black power in America, while John Carlos raised his left fist to represent black unity.

The International Olympic Committee president, Avery Brundage, immediately suspended Tommie Smith and John Carlos from the U.S. team and they were both removed from the Olympic Village. When they arrived home they received countless death threats. Australia's conservative media called for Peter Norman to be punished but Julius Patching, his team manager, refused to take action against him.

In 1969 Carlos equaled the world 100-yard record of 9.1, winning the AAU 220-yard run, and went on that year to lead San Jose State College to its first NCAA championship.

After leaving athletics Carlos played professional football with the Philadelphia Eagles of the National Football League. Plagued by injury problems he went to Canada and played one season each for the Montreal Alouettes and the Toronto Argonauts. Carlos also worked for the Puma Company, the United States Olympic Committee, and the City of Los Angeles.

In 1985, John Carlos became a counselor and in-school suspension supervisor as well as the Track & Field Coach, at Palm Springs High School. In 2003, he was elected to the National Track & Field Hall of Fame.

Primary Sources

(1) Dick Drake, Track and Field Magazine (November, 1967)

On Sept. 3 during this year's World Student Games in Tokyo, a Japanese reporter asked Tommie Smith, "In the United States, are the Negroes now equal to the whites in the way they are treated?" His obvious answer was, "No". The American Negro sprinter was then asked, "What about the possibility of (US) Negroes boycotting the 1968 Olympics?", a question probably prompted by comedian Dick Gregory's request—made at least partially in deference to the stripping of Muhammad Al's world heavyweight boxing title—that such an act be considered by Olympic prospects. Tommie's reply was, "Depending upon the situation, you cannot rule out the possibility that we (US) Negro athletes might boycott the Olympic Games."

This was the first occasion that Tommie Smith had been asked to reflect upon his thoughts concerning a boycott - either publicly or privately. The only previous publicly circulated statement on the boycott question by any American track and field athlete came from Ralph Boston, who, while he expressed a belief that it would not serve any purpose, did not categorically deny the possibility of such a development.

The world's most prolific global record holder has since denied that he is actively leading or advocating a boycott and has rebuked the idea that any outside individual or group from the black ranks has approached him. Tommie has affirmed that any withdrawal of Negro athletes from the Mexico Olympics would primarily come as a result of discussions among the athletes themselves.

The whole matter was further blown out of proportion when it was learned that Tommie and teammate Lee Evans were members of the executive committee for the United Black Students for Action (UBSA) at San Jose State, whose organization sought equality in housing, membership in social groups and in athletics during the first week of school this fall.

Pressmen the world over rushed to their typewriters to picture Tommie as a militant Negro leader or as an athletic stooge for extremist black groups and promptly scorned the merits of a boycott. What he has said, in effect, is two-fold: (1) I am concerned about the problems facing my race here and now, and (2) the Negro athletes might conclude that boycotting the Olympics would be an effectual tool in our battle for racial equality. No one at this stage knows whether a boycott will be forthcoming, and neither Tommie nor Lee is willing to conjecture at this time as to the possibility that it would actually transpire.

Talk to them, and you'll learn that their desire to participate in the Games is intense. They would have perhaps more to gain by winning a gold medal than the next white guy. And so, you must come to the question, what is it they feel so strongly about that they would sacrifice considerable personal glory and why would they consider jeopardizing their track careers? Reams of copy have been devoted to the possibility of such a boycott—and much of it based on misinformation--but little of it has dealt with the question of WHY the blacks would forfeit an opportunity to compete in the world's most important athletic event that many of them have already devoted countless hours striving to reach.

Thus, I invited Tommie and Lee to my apartment to express into an unbiased tape-recorder their views through a series of questions which I had hoped would shed some light on the confusion which has ensued since Sept. 3 and would unearth some of the deep-seated feelings which might result in US black athletes taking such an action as boycotting the Olympics.

The transcription that follows represents the opinions of two Negroes, who through personal insight, education, athletic achievement and world travel are becoming aware of the problems faced by the US black people and who are motivated and prepared to accept the responsibility of sacrificing their own personal achievement for a cause (not necessarily athletic boycott) they believe would aid in the cause of racial equality. As two non-militant, non-extremist Negroes, they are simply verbalizing the feelings of resentment and dissatisfaction perhaps typical of many of their brothers. As two prominent Negro athletes, their opinions about the possibility and effectiveness of a boycott do not necessarily represent the attitudes or desires of other Olympic Negro hopefuls.

Tommie and Lee, of course, are no strangers to the world of track nuts. On the strength of their track exploits alone, there are few athletes whose names are better known to the casual track fan. Between them, they claim at least portions of 11 world records.

Tommie, now 23 and still a student at San Jose State though without further track eligibility, holds world records at 200-meters and 220-yards straightaway (19.5), 200-meters and 220-yards turn (20.0), and has marks pending in the 400-meters (44.5) and 440-yards (44.8) as well as indoor marks in the 400-meters and 440-yards (46.2). Both Tommie and Lee ran on their school's world record 800-meter and 880-yard relay (1:22.1) and on the US national team that claims the world standard in the 1600-meter relay (2:59.6). They also ran on the San Jose State team that bettered the American standard in the mile relay (3:93.5).

Lee, three years younger and a junior in eligibility, ranked number one in the world last year in the quarter mile by T&FN. His 44.9 for 400-meters is equal second best of all-time. He had lost only to Tommie (in the world record 400/440) this year until injured in Europe. Neither has competed on an Olympic team though both have taken foreign tours with US teams.

Because these pages are devoted to athletics, we must necessarily limit the discussion that developed to those aspects that at least indirectly relate to track and field. Both Tommie and Lee have read this report in its entirety and at least concur as to its factual content. Whether or not you agree with the merits of a US Negro boycott of the 1968 Olympics, you should find the reasons that would motivate such an action revealing.

QUESTION: Has there been any single major event which has prompted the suggestion that Negroes boycott the Olympics? What role did the stripping of Muhammad Ali's boxing title and Dick Gregory's subsequent request that Negroes boycott the Games play in the current thinking?

EVANS: What Dick Gregory said doesn't have much to do with what I feel. I think that many Negroes are becoming aware of what's happening. In high school, I didn't know what was coming off, but in college I have become aware and concerned. Of course, what they did to Ali affects my opinion. I just don't dig some of the things that are happening.

QUESTION: What is the objective of such a movement? What do you and others hope can be achieved with a boycott? Do you think any concrete results can be achieved? Or is it merely symbolic?

EVANS: In terms of what I have put into the sport, I think that I will be really hurt, But, then you begin thinking about what the Negro has been going through in this country. When you come back from the Olympics with a gold medal, you might be high on the hog for a month, but after that you would be just another guy. Look at Bob Richards on TV. Why don't they have Bob Hayes or Henry Carr advertising on TV? If they had them advertising Wheaties, some of the white people in the south might stop purchasing their product. As for myself, I would be most interested in seeing something done now so that things would be different by the 1972 Olympics.

SMITH: There have been a lot of marches, protests and sit-ins on the situation of Negro ostracism in the US. And I don't think that this boycott of the Olympics would stop the problem, but I think people will see that we will not sit on our haunches and take this sort of stuff. We are a race of proud people and want to be treated as such. Our goal would not be to just improve conditions for ourselves and teammates, but to improve things for the entire Negro community.

You must regard this suggestion as only another step in a series of movements. Maybe discrimination won't stop in the next 10 years but it will represent another important development. As far as being spit on, being stepped on, being bitten by dogs, the first dog that bites me I'm going to bite back. We're not going to wait for the white man to think of something else to do against us - as in politics which is currently working against us. And it doesn't do any good to put an Uncle Tom into high position. I have worked for a long time for the Olympics, and I would hate to lose all that. But I think that boycotting the Olympics for a good cause is strong enough reason not to compete.

EVANS: I think Negroes are realizing that the white man doesn't go by his own rules, such as in civil rights. To the extent that I think things would be different for the American Negro by 1972, I am willing to consider boycotting. We are men first and athletes second. Professional athletes are even quitting now because of prejudice.

QUESTION: What prompted you, Tommie, to comment about the possibility of a boycott in Japan?

SMITH: My comments in Japan came as a result of quite a bit of listening and reading and thinking for myself. The reporter asked me about the possibility of a boycott. I told him that there is a chance, and the reason was literally because of the ostracism of the US Negro. I had made no comment prior to then. I was not motivated to comment as the result of anything Ralph Boston or Dick Gregory had said.

QUESTION: Is there any group or individual behind the proposal for a boycott?

SMITH: I couldn't say, but no one has approached me. It's up to the Negro athletes to decide, and we have not met as a group to discuss the boycott. There will be a Black Youth Conference in Los Angeles. November 23, on which occasion we will discuss the possibilities with athletes from other sports as well. This meeting will not include all the major track and field athletes, but I think we will draw a lot of conclusions. Again, I'm not advocating the boycott.

QUESTION: How serious is the possibility of a boycott? What are the chances that it will transpire?

EVANS: There is a chance it will happen. But it just depends. The guys in California would give up the opportunity to compete; they'd hate to but then you've got to do something. But then there are the athletes from the other 49 states. I really want to go to the Olympics, but I'll pass it up if I have to--for a just cause.

SMITH: I think a close enough decision will develop at this meeting to know what will happen.

EVANS: If everyone is willing to do it, I'm sure we're going to do it.

QUESTION: Of the Negro athletes you've talked with, what percent would you say support or would support a boycott?

EVANS: You have to go to different sections of the country. I think in California, it would be 75% right now. But if you go to the south or southwest these are the guys who are catching the most hell in the streets and they just don't understand the need for a boycott. The schools in the south simply aren't the same as in the west. So, these guys aren't aware of what's happening. The schools don't get them to thinking, and the guys don't read about the problems. They don't think about their jobs and what their parents were doing. They're just thinking about themselves and what the Olympics would mean.

SMITH: Some of these guys from the south look at you funny. But look at it this way. How would you like it if you said something in California and you got back to your home in the south to find a double barrel shotgun sticking in your front door? I think the guys are more afraid than anything.

QUESTION: What has motivated your current activist roles?

SMITH: Thinking.

EVANS: Thinking.

SMITH: Like Lee says, as a senior in high school I looked upon my ability as something no one else had, and looking at this ability alone I neglected to realize there might be something else to life than just track. It's only been in the last two years that I have begun to see that there are problems, and that I must learn to cope with them. And I'm starting by looking at myself.

QUESTION: How have your opinions altered in the past six weeks since going on record about all this?

SMITH: It has forced me to read and think about the problems of this day and age—even more than six months ago. If this individual in Japan would not have asked me about the possibility of a boycott in 1968, I might not have begun really thinking about this specific suggestion. All of a sudden something suddenly flashed into my mind. Is there something to it? What is this individual asking me? Am I going to take the ostracism I'm taking now, or if this Japanese knew this, where did it come from?

QUESTION: Could you give up athletics tomorrow?

SMITH: I would give up athletics tomorrow if the cause were strong enough. I would give up athletics in a minute to die for my people.

QUESTION: What about the challenges that you, Tom, have lost your humility with respect to what athletics has given you? What is your reaction to columns such as the one by Jim Murray of the Los Angeles Times wherein he called you a downy-cheeked kid who has an exaggerated opinion of his own athletic importance?

SMITH: There are some people who are pen happy. As far as Murray's standpoint, I think he is looking at it all on a narrow line and not objectively. I don't think most writers are like this, but Murray is. Because he has said something about me that wasn't true. One quotation in particular bothered me, and that was that I was advocating a boycott. And then there were a lot of smaller things that added up to one big lie. To the average individual, it made me look like something lower than a rat.

EVANS: It made Tommie look like militant Tommie. As soon as you become aware of what is happening to your people, you are considered militant. UBSA is considered a militant group because we got things done on the campus. That campus is a lot better now. And other campuses could be as well if they'd just do something.

QUESTION: Why boycott only the Olympics? Why single them out for boycotting, while continuing to compete for a school which has been charged with discrimination and in a country where it exists?

EVANS: The school is just a part of this country. So, I think we should hit at the top. And this country—I can't dig why the US voted to permit South Africa to compete in the Olympics. That was what I was told, anyway. I'm definitely going to discuss this matter at this conference. They send this cat Paul Nash to run here in the US. If I went to South Africa, they wouldn't let me run in no damn meet with Paul Nash. But he can come here and run with us. I'm supposed to be an American, but I'm not treated as one.

Coach Stan Wright wrote Tommie a letter telling him that he should consider himself an American first, a Negro second. But nobody else considers me an American first. You read any kind of book or magazine. Even Track & Field News says Negro Stan Wright. The first thing you're told or see is that you're a Negro, but still you're supposed to be an American. If you publish a picture, people can look at it and tell if you're Negro. So, you don't have to mention it.

SMITH: What kind of logic is this to let Paul Nash come to America to compete for South Africa. Lee or (Ralph) Boston or myself cannot go as Americans to compete in South Africa. Now, if we are Americans, if (Jim) Ryun and I are both Americans, why can't I go to South Africa and compete in the same meets? If we can't go there, why can they come here?

EVANS: This is where you can hit them the hardest. This is one of the major areas where the US gets its international sports propaganda. The Olympics are a big thing, and the press help to create this. So, if the people want us Negroes) to help promote US sports propaganda, they can help us too.

SMITH: Why should we boycott the Olympics instead of the meets at our college? A good percentage of the Negroes are in college because of a scholarship. Now, if we discontinue athletics, the scholarship almost means our lives to us. I got my education through a scholarship. If I had discontinued competition, it would have meant that my scholarship would have been taken away. Therefore, I wouldn't have gotten an education and gotten as far as I have, and so I wouldn't know what I'm talking about. Education is a prelude to a later advancement in life: knowledge. Therefore, unless you have the financial background, discontinuing athletics wouldn't be advantageous to any cause. You have less to lose and more to gain by boycotting the Olympics than at San Jose State—because this is the way you have hit the hardest.

QUESTION: When did you sense a change in your opinions?

SMITH: It began when I started walking and thinking I am a Negro. I wish I could give you a definite date. I said, here's a white man, I'm a Negro. He can walk into this store, why can't I? It really started last semester, and then Tokyo helped. I took a class in black leadership; it started me to thinking. What the hell is going on in the US? I'm a human. What kind of rights do I have? What kind of rights don't I have? Why can't I have these rights?

EVANS: I started reading. That's what got me to thinking.

QUESTION: Have you experienced any blatant or subtle discrimination on international track teams?

EVANS: [Lee related two incidences concerning John Carlos and George Anderson at the US-Commonwealth meet which he felt were either the result of misunderstandings or were sufficiently remedied so as not to be classifiable as acts of discrimination.] But we were going to boycott that meet as a Negro block if they didn't use the first four finishers in the American women's 100-yard dash at the AAU in the relay—who all happened to be Negroes. They intended to substitute Dee DeBusk for Mattiline Render. But as it turned out, Barbara Farrell got injured, so both Dee and Mattiline got to run. And that saved the situation.

QUESTION: How do you professors at San Jose State regard you in general?

EVANS: They know us as the fastest ****** on campus. They only talk to us because we're athletes. They don't talk to the next Negro who passes by.

SMITH: Often, they say congratulations to me. I say, "Thank you. What did I do?" I say, "On my marriage or on a test?" And they say, "No, on your world record." They never talk about my marriage or academics.

EVANS: You are a fast ******. They don't say ****** but that's what—they mean.

SMITH: There's one coach who doesn't think that the Negroes can have any sentimental value. And when he looks at you, he regards you only as an athlete. And he tries to find the easiest classes for you so you can get through college. Now, how the hell are you going to get an education with 15 units of badminton?

EVANS: You get a sheet from them that says what it takes to get through college.

SMITH: I'm taking a couple of courses that I have no interest in. But I have to take them. Look at ROTC, for example. As a result of my lack of interest, I'm not getting good grades. Why should I go to Viet Nam and fight for this country and come back when my equality will still be half taken away? If I could come back here just like my white friends, I'd be happy to be a lieutenant in the Army.

The following statements by Tommie and Lee were issued to the press at large, and will serve as their concluding comments to this interview.

EVANS: My own position on a boycott is this: the Olympics are something that I have dreamed of participating in ever since I first learned to run. This does not, however, mean participation at any price. And my own manhood is one of the prices that I am not willing to pay. A second and more important price that I am not under any circumstances willing to pay is that of slamming a potential door to freedom in the face of black people. If this door can be opened by my not participating, then I will not participate.

SMITH: I want to clarify several points that I am alleged to have made at a recent speaking engagement in Lemoore, California. Several points that I made were taken completely out of context. The Olympic Games are and always have been of extreme importance and significance to me. I did make the statement that I would give my right arm to participate and win a gold medal, but it was taken out of context as I am not willing to sacrifice the basic dignity of my people to participate in the Games.

I am quite willing not only to give up participation in the Games but my life as well if necessary to open a door by which the oppression and injustices suffered by black people in the US might be alleviated. If the group decision is to boycott, I will participate wholeheartedly.

(2) BBC Report (17th October, 1968)

Two black American athletes have made history at the Mexico Olympics by staging a silent protest against racial discrimination.

Tommie Smith and John Carlos, gold and bronze medallists in the 200m, stood with their heads bowed and a black-gloved hand raised as the American National Anthem played during the victory ceremony. The pair both wore black socks and no shoes and Smith wore a black scarf around his neck. They were demonstrating against continuing racial discrimination of black people in the United States.

As they left the podium at the end of the ceremony they were booed by many in the crowd.

At a press conference after the event Tommie Smith, who holds seven world records, said: "If I win I am an American, not a black American. But if I did something bad then they would say 'a Negro'. We are black and we are proud of being black. "Black America will understand what we did tonight." Smith said he had raised his right fist to represent black power in America, while Carlos raised his left fist to represent black unity. Together they formed an arch of unity and power. He said the black scarf represented black pride and the black socks with no shoes stood for black poverty in racist America. Within a couple of hours the actions of the two Americans were being condemned by the International Olympic Committee. A spokesperson for the organisation said it was "a deliberate and violent breach of the fundamental principles of the Olympic spirit." It is widely expected the two will be expelled from the Olympic village and sent back to the US.

In September last year Tommie Smith, a student at San Jose State university in California, told reporters that black members of the American Olympic team were considering a total boycott of the 1968 games.

He said: "It is very discouraging to be in a team with white athletes. On the track you are Tommie Smith, the fastest man in the world, but once you are in the dressing rooms you are nothing more than a dirty Negro." The boycott had been the idea of professor of sociology at San Jose State university, and friend of Tommie Smith, Harry Edwards. Professor Edwards set up the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR) and appealed to all black American athletes to boycott the games to demonstrate to the world that the civil rights movement in the US had not gone far enough. He told black Americans they should refuse "to be utilised as 'performing animals' in the games."

Although the boycott never materialised the OPHR gained much support from black athletes around the world.

(3) John Carlos: Inducted to Hall of Fame (1993)

John Carlos was born in Harlem, New York in 1945. After graduating from Machine Trade and Medal High School, he was awarded a full track and field scholarship to East Texas State University (ETSU). He attended ETSU for one year, single-handedly winning the schools first and only track and field Lone Star Conference Championship. After ETSU, he matriculated to San José State University.

During his stay at San José State University, he participated in the 1968 Mexico Olympics and won the bronze medal in the 200 meters. During the victory ceremony, John and Tommy Smith raised a black gloved fist in protest against racism and economic depression for all opposed peoples. This "Silent Protest" was voted as the sixth most memorable event of the century.

Following the Mexico Olympics, John Carlos continued his education and athletic feats at San José State University where he single handily won the NCAA Track & Field National Championship in 1969. During his stay, he broke the world record in the hundred-yard dash. Concluding an illustrious career in track and field, John Carlos was drafted by the NFL. After a short career in the NFL, he entered the public sector, working for PUMA, the Olympics, and the City of Los Angeles.

Presently, John Carlos is working as the Track & Field Coach, and an In-school Suspension Supervisor for Palm Springs High School in Palm Springs, California.

(4) Dave Zirin, CounterPunch (1st November, 2003)

Thirty-five years ago, John Carlos became one half of perhaps the most famous (or infamous) moment in Olympic history. After winning the bronze medal in the 200 meter dash, he and gold medallist Tommy Smith, raised their black glove clad fists in a display of "black power." It was a moment that defined the revolutionary spirit and defiance of a generation. Now as the 35th anniversary of that moment passes with nary a word, John Carlos talks about about those turbulent times.

DZ: Many call that period of the 1960s, the revolt of the black athlete. Why?

JC: I think Sports Illustrated started that phrase. I don't think of it as the revolt of the black athlete at all. It was the revolt of the black men. Athletics was my occupation. I didn't do what I did as an athlete. I raised my voice in protest as a man. I was fortunate enough to grow up in the era of Dr. King, of Paul Robeson, of baseball players like Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella who would come into my dad's shop on 142nd street and Lennox in Harlem. I could see how they were treated as black athletes. I would ask myself, why is this happening? Racism meant that none of us could truly have our day in the sun. Without education, housing, and employment, we would lose what I call "family hood." If you can't give your wife or son or daughter what they need to live, after a while you try to escape who you are. That's why people turn to drugs and why our communities have been destroyed. And that's why there was a revolt.

DZ: When you woke up that morning in 1968, did you know you were going to make your historic gesture on the medal stand or was it spontaneous?

JC: It was in my head the whole year. We first tried to have a boycott [to get all Black athletes to boycott the Olympics] but not everyone was down with that plan. A lot of the athletes thought that winning medals would supercede or protect them from racism. But even if you won the medal it aint going to save your momma. It aint going to save your sister or children. It might give you 15 minutes of fame, but what about the rest of your life? I'm not saying they didn't have the right to follow their dreams, but to me the medal was nothing but the carrot on a stick

DZ: At the last track meet before the Olympics, we left it that every man would do his own thing. You had to choose which side of the fence you were on. You had to say, "I'm for racism or I'm against racism."

JC: We stated we were going to do something. But Tommie and I didn't know what we were going to do until we got into the tunnel [on the way to the race].. We had gloves, black shirts and beads. And we decided in that tunnel that if we were going to go out on that stand, we were going to go out barefooted.

DZ: Why Barefooted?

JC: We wanted the world to know that in Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee, South Central Los Angeles, Chicago, that people were still walking back and forth in poverty without even the necessary clothes to live. We have kids that don't have shoes even today. Its not like the powers that be can't do it provide these things. They can send a space ship to the moon, or send a probe to Mars, yet they can't give shoes? They can't give health care? I'm just not naive enough to accept that.

DZ: Why did you wear beads on the medal stand?

JC: The beads were for those individuals that were lynched, or killed that no one said a prayer for, that were hung tarred. It was for those thrown off the side of the boats in the middle passage. All that was in my mind. We didn't come up there with any bombs. We were trying to wake the country up and wake the world up too.

DZ: How did your life change when you took that step onto the podium?

JC: My life changed prior to the podium, I used to break into freight trains by Yankee Stadium when I was young. Then I changed when I realized I was a force in track and field. I realized I didn't have to break into freight trains. I wanted to wake up the people who work and run the trains so they can seize what they deserve. It's like these supermarkets in Southern California that are on strike. They always have extra milk and they throw it in the river or dump it the garbage even though there are people without milk. They say we can't give it to you so we would rather throw it away. Something is very wrong. Realizing that changed me long before 1968.

DZ: What kind of harassment did you face back home?

JC: I was with Dr. King ten days before he died. He told me he was sent a letter that said there was a bullet with his name on it. I remember looking in his eyes to see if there was any fear, and there was none. He didn't have any fear. He had love and that in itself changed my life in terms how I would go into battle. I would never have fear for my opponent, but love for the people I was fighting for. That's why if you look at the picture [of the raised fist] Tommy has his jacket zipped up, and [silver medallist] Peter Norman has his jacket zipped up, but mine was open. I was representing shift workers, blue-collar people, and the underdogs. That's why my shirt was open. Those are the people whose contributions to society are so important but don't get recognized.

DZ: What kind of support did you receive when you came home?

JC: There was pride but only from the less fortunate. What could they do but show their pride? But we had black businessmen, we had black political caucuses, and they never embraced Tommie Smith or John Carlos. When my wife took her life; 1977 and they never said, let me help.

DZ: What role did you being outcast have on your wife taking her own life?

JC: It played a huge role. We were under tremendous economic stress. I took any job I could find. I wasn't too proud. Menial jobs, security jobs, gardener, caretaker, whatever I could do to try to make ends meet. We had four children, and some nights I would have to chop up our furniture and put it in the fireplace to stay warm. I was the bad guy, the two headed dragon-spitting fire. It meant we were alone.

DZ: Many people say athletes should just play and not be heard. What do you say to that?

JC: Those people should put all their millions of dollars together and make a factory that builds athlete-robots. Athletes are human beings. We have feelings too. How can you ask someone to live in the world, to exist in the world, and not have something to say about injustice?

DZ: What message do you have to the new generation of athletes hitting the world stage?

JC: First of all athletes black/red/brown/yellow and white need to do some research on their history; their own personal family They need to find out how many people in their family were maimed in a war. They need to find out how hard their ancestors had to work. They need to uncloud their minds with the materialism and the money and study their history. And then they need to speak up. You got to step up to society when it's letting all its people down.

DZ: As you look at the world today, do you think athletes and all people still need to speak out and take a stand?

JC: Yes, because so much is the same as it was in 1968 especially in terms of race relations. I think things are just more cosmetically disguised. Look at Mississippi, or Alabama. It hasn't changed from back in the day. Look at the city of Memphis and you still see blight up and down. You can still see the despair and the dope. Look at the police rolling up and putting 29 bullets in a person in the hallway, or sticking a plunger up a man's rectum, or Texas where they dragged that man by the neck from the bumper of a truck. How is that not just the same as a lynching?

DZ: Do you feel like you are being embraced now after all these years?

JC: I don't feel embraced, I feel like a survivor, like I survived cancer. It's like if you are sick and no one wants to be around you, and when you're well everyone who thought you would go down for good doesn't even want to make eye contact. It was almost like we were on a deserted island. That's where Tommy Smith and John Carlos were. But we survived.

(5) Dave Zirin, Common Dreams (20th October, 2005)

Trepidation should be our first impulse when we hear that radical heroes are to be immortalized in fixed poses of bloodless nostalgia. There is something very wrong with seeing the toothy, grinning face of Paul Robeson staring back at us from a stamped envelope. Or the wry expression the US Postal service affixed on Malcolm X - harmless, wry, inviting, and by extension slanderous.

These fears erupted in earnest when I heard that San Jose State University would be unveiling a statue of two of its alums, Tommie Smith and John Carlos. The 20 foot high structure would be a commemoration of their famed Black Gloved salute at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City. I dreaded the thought that this would be the athletic equivalent to Lenin's Tomb: when you can't erase a radical history, you simply embalm it.

These fears are not without foundation. Smith and Carlos's frozen moment in time has been consumed and regurgitated endlessly by the wide world of corporate sports. But this process has taken place largely without any kind of serious discussion about who these men were, the ideas they held, and the price they paid.

With palpable relief, I report that the statue does Smith and Carlos justice, and then some. It is a lyrical work of art, and a fitting tribute to two amazing athletes who rose to their moment in time. Credit should go to the artist, a sculptor who goes by the name Rigo23. Rigo23's most important decision was to leave Smith and Carlos's inventively radical and little discussed symbology intact. On the statue, as in 1968, Smith and Carlos wear wraps around their necks to protest lynching and they are not wearing shoes to protest poverty. Rigo23 made sure to remember that Carlos' Olympic jacket - in a shocking breach of etiquette - was zipped open, done so because as Carlos said to me, "I was representing shift workers, blue-collar people, and the underdogs. That's why my shirt was open. Those are the people whose contributions to society are so important but don't get recognized."

The most controversial aspect of the statue is that it leaves off Australian silver medalist Peter Norman altogether. This seems to do Norman a disservice considering that he was not a passive player in 1968 but wore a solidarity patch on his Olympic jacket so the world would know which side he was on.

But Rigo23 did this, over the initial objections of John Carlos, so people could climb up on the medal stand with Smith and Carlos and do everything from pose for pictures to lead speak-outs. Norman who traveled to the unveiling ceremony from Australia endorsed the design wholeheartedly understanding that its purpose is less to mummify the past than inspire the future. "I love that idea," said Norman. "Anybody can get up there and stand up for something they believe in. I guess that just about says it all."

Perhaps the main reason the statue is so good, so different, from things like Martin Luther King, Jr. shot glasses and Mohandas Ghandi mouse pads, is that it was the inspiration not of the school's Board of Trustees but a group of students who pushed and fought for the school to pay proper respect to two forgotten former students that epitomized the defiance of a generation.

And, fittingly, the day of the unveiling was not merely a celebration of art or sculpture but a bittersweet remembrance of what Smith and Carlos endured upon returning to the United States, stripped of their medals and expelled from Olympic Village. Smith recalled, "The ridicule was great, but it went deeper than us personally. It went to our kids, our citizen brothers and our parents. My mother died of a heart attack in 1970 as a result of pressure delivered to her from farmers who sent her manure and dead rats in the mail because of me. My brothers in high school were kicked off the football team, my brother in Oregon had his scholarship taken away. It was a fault that could have been avoided had I turned my back on the atrocities."

Carlos also said, "My family had to endure so much. They finally figured out they could pierce my armor by breaking up my family and they did that. But you cannot regret what you knew, to the very core of your person, was right."

But it was also a day to speak explicitly about the challenges of the future and not turning living breathing struggles into a history that is an inanimate as a hunk of marble. "Will Smith and Carlos only be stone-faced amidst a beautiful plaza?" speaker Professor Ethel Pitts-Walker asked the crowd. "For them to become immortalized, the living must take up their activism and continue their work."

Peter Norman said, "There is often a misunderstanding of what the raised fists signified. It was about the civil rights movement, equality for man....The issues are still there today and they'll be there in Beijing [at the 2008 summer games]and we've got to make sure that we don't lose sight of that. We've got to make sure that there is a statement made in Beijing, too. It's not our part to be at the forefront of that, we're not the leaders of today, but there are leaders out there with the same thoughts and the same strength."

But the last word went to Tommie Smith, proud of the past but with an understanding of the challenges in the future. "I don't feel vindicated," Smith said. "To be vindicated means that I did something wrong. I didn't do anything wrong. I just carried out a responsibility. We felt a need to represent a lot of people who did more than we did but had no platform, people who suffered long before I got to the victory stand...We're celebrated as heroes by some, but we're still fighting for equality."

Fittingly, when it came time to unveil the statue, the Star Spangled Banner was played -as a symbol of "how far we've come" since 1968. There was one problem: the curtain became snagged on the statue's raised fists. In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, we need our anti-racist history and our anti-racist heroes now more than ever. We need more fists gumming up the works.