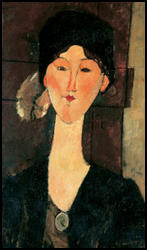

Beatrice Hastings

Emily Alice Haigh (Beatrice Hastings) was born in Port Elizabeth in the Cape Colony of South Africa in 1879. As a child she was sent to boarding school in Pevensey. Later she took the name of Beatrice Hastings and developed a career in journalism.

A member of the Social Democratic Federation, Beatrice Hastings was a political activist who contributed articles to the socialist magazine New Age. Hastings was also a member of the Society for Abolition of Capital Punishment and the Penal Reform League.

Along with her friend, Annie Besant, Hastings was a strong supporter of Madame Blavatsky. Beatrice Hastings also helped to discover Katherine Mansfield and arranged for her work to be published in New Age.

In 1909 Hastings joined forces with C. H. Norman, to campaign to get John Dickman a retrial. Norman had worked as a shorthand writer at the original trial and was convinced that there had been a miscarriage of justice.

Hastings was an attractive woman who had no difficulty attracting men. She claimed that she made notches on her bedpost for all her successes.

In 1914 Hastings moved to France and shared an apartment in Montparnasse with Amadeo Modigliani, the famous artist. She was also very close to Jean Cocteau. Hastings wrote a regular column for New Age while in France under the name Alice Morning.

Hastings moved back to England and settled in Worthing where she published two books, The Old New Age - Orage and Others (1935) and The Defence of Madame Blavatsky (1937).

Beatrice Hastings, suffering from cancer, committed suicide in 1943. According to her biographer: "In the gas-filled apartment in which her body lay, the remains of her pet mouse were found along with her own."

Primary Sources

(1) Beatrice Hastings, New Age Magazine (11th August, 1910)

The question of Dickman’s guilt or innocence would no doubt be settled satisfactorily for a certain type of mind by the news of his execution.. As one Newcastle paper obsequiously observed after the failure of appeal: “The last doubter should now be satisfied that the verdict given at the Assizes was the right one.“ The forty thousand "last doubters,” including three of the jurymen, are still, at this moment, protesting that the verdict was a wrong one, and that the Appeal Court decision was a grim farce. We, noted at that court how the Lord Chief Justice had come to praise his learned colleague. Lord Coleridge staked more than his own reputation in revealing that trade stock of legal platitudes and clichés and of tricks of suggestion and suppression - so old that some of them have Sanskrit names. The pride and honour of the Bar are none too secure in these scientific days. Lord Alverstone may go blue in the face protesting that he doesn’t care tuppence for public opinion. Justice PhiIlimore may burst himself in the Appeal Court laughing at John William Smith’s seven epileptic relatives, and justice Darling may denounce "these theories of atavism and irresponsibility of which the air is full ” (though goodness only knows how the learned judge heard the news). The fact is that many a young student is better equipped to decide a murder charge than these elderly experts in the letter of the law.

Judges have never been popular; but, in these days their unpopularity seems clearer because humane persons speak more decidedly, knowing that science is behind them. It is significant that judges should give each other loud cheers over post-prandial boasts of their indifference to public opinion. Some noise is needed to drown the growing clamour of public opinion against the crime of judicial murder; murder of epileptics, murder of men condemned on circumstantial evidence, murder of boys under age, and of imbeciles. I have cases of all four on my records. No amount of judicial boasting, however, will impress persons who realise how sadly the times have changed for judges since 1833, when Mr. Justice Bosanquet luxuriously sentenced to death a housebreaker of nine years of age; since 183 I, when a lad of fourteen was hanged at Maidstone; nay, since 1907, when Thomas Parrett, an imbecile, aged sixteen, was sentenced to death at Crewe by the Lord Chief Justice - this very Lord Chief Justice who found Judge Coleridge’s attack on Dickman so “fair and able ” as seldom he had ever read!

Let us take a sample of this fair and able summary. About the stain on Dickman’s gloves, a stain which might have been fish blood. Lord Coleridge said : “The suggestion of the prisoner in respect of this was that his nose bled, but this might not appear to them a satisfactory explanation.

The prisoner did not say that on that day his nose bled.Very good reason why: his nose did not bleed on

that day, and - a small matter this, of course - his evidence on oath was that he was not wearing those gloves on “ that” day.

How differently evidence against this prisoner influenced Lord Coleridge! Hall, who omitted to tell the jurymen of his little peep at Dickman through the window. Hall is positively apotheosised. In commenting upon this witness’s evidence the judge became rhetorical. “There are some persons so proud of their accuracy that in that very pride one may discover grounds for doubt. There are other persons scrupulous, careful, conscientious, etc.”

Hall’s evidence needs a few adjectives to draw a curtain over that window episode. Mrs. Nisbet, too, who omitted to tell the jury that she had known Dickman for years - but probably no one but a judge would judge this afflicted woman one way or another; merely putting aside her evidence. I say here, however, that it is a pity for the sake of justice that women are not on the jury. In the middle of his summary Judge Coleridge made a table of the net result of the evidence “so far.”

1. The deceased was in the third compartment of the third coach.

2. He was murdered between Stannington and Morpeth.

3. There was one man and one man alone in the carriage with him - certainly between Heaton and Morpeth.

4. The prisoner was seen with the deceased at the station in Newcastle apparently in companionship with him.

5. The prisoner was seen with a companion getting into a compartment that was approximate at any rate to the one in which deceased was travelling.

That’s the “net result.” Not a word of the defence, although the defence. Of this numbered evidence, No. 2 is a lie. It has never been proved to this moment where Nisbet was murdered. No. 3 depends on Mrs. Nisbet’s Identification. No. 4 depends on Hall’s identification. No. 5 depends upon Hepple’s identification. Except for Hepple, Dickman would probably never have been charged. Hepple passed this man he had known for twenty years at a distance of eighteen feet, yet he never bade him good morning, nor did the twenty years’ friend give any greeting.

Distinctly fishy! Dickman’s evidence was that he was already seated in another part of the train, and never saw Hepple at all.

Clearly, from the moment Hepple swore to Dickman and the police discovered, from Dickman himself, that he had no alibi, the man, if innocent, was in a horrible trap.

Lord Coleridge, for the sake of argument, at one period chose to imagine Dickman as guilty, and he examined on that hypothesis the prisoner’s story of his movements. "If you believe it,” he commented, after this able but unfair hit at the prisoner "if you believe it, you must seek elsewhere for the murderer... There is no corroborative evidence that the prisoner had been on this road at all. Naturally, of course, a guilty man would seek in any may he could lay his hands on (sic) to account, otherwise than how it was spent, for the spending of that crucial interval.”

Lord Coleridge fought Dickman - who had had no breakfast each day but at 7.15 - as if this man were the grince of criminal intellects. What an ass he would have been however, on the judge’s eternal supposition that he had planned the murder with marvellous foresight, to have provided no better story but that he went for a walk and was taken ill. That explanation seems too simple to be untrue. Counsel for the defence was ably undermined once or twice. “Dickman has been treated for this sickness in prison,” counsel interrupted. His lordship observed that he had suffered from a malady no doubt.“ Does it not commend itself to your good sense,” the judge addressed the jury a few minutes later, “your good sense (a very able touch, this piffling moral bribery) that a clever guilty man would have said as much truth as possible without implicating himself?”

If to drum in the minds of the jury a disbelief of every word uttered by the accused, if that is ability, then no

doubt Lord Coleridge was temporarily very able, even though three of his moral victims soon turned upon him and upon themselves and remorsefully signed for Dickman’s reprieve.

I have previously referred to Lord Coleridge’s rule in summing-up this case, so that every hint, every suspicion, every bit of evidence against the accused was arranged to strike last upon the minds of the jury. This method, successful as it was in oratory, thumps monotonously through pages of writing.

Turning from this tedious, inhuman though expert hammering upon a man in a trap, it is interesting to note that extraordinary charges have been brought against Dickman, no, no, never brought, only hinted and spread far and wide!

It has been told me on “high authority” that the Home Office knows - only it cannot prove - that Dickman did “at least” two other murders and many forgeries, ever so many forgeries. The Luard murder was hinted at! Also the prosecution knew quite well, only it could not prove, that Dlckman actually had pistols. An old man was shot in Sunderland some time ago. Dickman... but Heaven defend us all if the authorities are going to judge us on secret information - too secret, too damned secret, to be made public. It is obvious that on the public evidence a reprieve was imperative. The Home Office must therefore have taken into account information not available for the public; that is, evidence, of so unsupported a character that it would not bear public investigation. I have personally received letters of unexampled spitefulness, testifying to the local prejudice and the determination to have some man or other bloodily executed for this crime. The authorities, for their part, are notoriously exasperated to have the Gorse Hall, the Luard and the Sunderland murders still unexplained.

The rumours that another warrant was out for Dickman proceeded from the police and no one else! Whether Dickman was guilty or innocent may never be known, but what is certain to grow in the public mind is the suspicion that his death was determined upon to satisfy the police and to save Lord Coleridge’s reputation. When an innocent man is convicted, the judge is condemned. Dickman on the evidence was doubtfully guilty. Lord Coleridge is more than doubtfully innocent.

(2) Canadian Theosophist (January 1944)

I had a letter dated 11th, from Mr. Hugh Williamson of Boston, enclosing a clipping from a Worthing paper, which he had received from that place. It gave an account of the inquest which had been held on Mrs. Hastings' body which had been found dead in her own kitchen with the gas turned on. Miss Green gave evidence that she was nurse-secretary to Mrs. Hastings, who lived alone at 4 Bedford Row. Medical evidence was to the effect that deceased must have suffered "considerable pain" for a long period from the condition of her internal organs. Those who have witnessed the agonizing sufferings of cancer patients can perhaps understand how the tormented body desires to end its torture. "The coroner returned a verdict of suicide while the deceased was mentally unhinged."