War Economy

The first budget of the Second World War was introduced by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Sir John Simon, in September, 1939. The standard rate of income tax was increased from five shillings and sixpence to seven shillings. An extra penny was added to the tax on a pint of beer. There were also extra taxes on sugar and tobacco. Simon also introduced a new Excess Profits Tax of 60 per cent on the war industries.

The country's leading economist, John Maynard Keynes, argued that this would not be enough to pay for the war and advocated a drastic increase in taxation.

In the 1930s Britain imported about 55 million tons of food a year from other countries. Understandably, the German government did what they could to disrupt this trade. One of the main methods used by the Germans was to get their battleships and submarines to hunt down and sink British merchant vessels.

With imports of food and other goods declining, prices began to rise. Food prices increased by about 15 per cent during the first six months of the war. This upset the trade unions and they began to demand wage increases for their members. The government reacted by providing £60 million a year to subsidise the price of basic foods.

The British government decided to introduce a system of rationing. This involved every householder registering with their local shops. The shopkeeper was then provided with enough food for his or her registered customers. In January, 1940, bacon, butter and sugar were rationed. This was followed by meat, fish, tea, jam, biscuits, breakfast cereals, cheese, eggs, milk and canned fruit.

There was also a shortage of workers in essential war industries such as engineering and shipbuilding. The government, against the wishes of the trade unions, passed the Control of Employment Act. This enabled them to bring in semi-skilled and unskilled workers to do jobs previously done by skilled workers.

In April 1940 Sir John Simon introduced a new budget. The standard rate of income tax was increased from seven shillings to seven shillings and sixpence. An extra penny was added to the tax on a pint of beer. There were also extra taxes on tobacco. The most controversial measure was to increase postal charges. This especially upset members of the armed forces who were serving abroad as they feared it might reduce the number of letters they received from their families.

During the war the government decided to restrict the supplies of non-essential consumer goods to the home market. In June 1940 the government issued the Limitation of Supplies Order. This cut the production of seventeen classes of consumer goods to two-thirds of the 1939 level. This included toys, jewellery, cutlery and pottery.

From 1938 to 1944 the cost of living rose by 50 per cent, whilst weekly earnings rose by just over 80 per cent. The government tried to persuade the people of Britain to invest this extra money into National Savings schemes such as Warship Week and Wings for Victory. However, much of this money was used to buy black market goods and a dramatic increase in gambling.

The cost of the war increased throughout the war. On 4th June 1941, the new Chancellor of the Exchequer, Kingsley Wood, the cost of the war was on average £10,250,00 (£410,000,000) a day.

Primary Sources

(1) Henry (Chips) Channon, diary entry (14th September, 1939)

The first war budget. At 3.45 Simon rose (he was directly in front of me) and in unctuous tones not unlike the Archbishop of Canterbury, opened his staggering budget. He warned the House of its impending severity yet there was a gasp when he said that Income Tax would be 7/6 in the £. The crowded House was dumbfounded, yet took it good-naturedly enough. Simon went on, and with many a deft blow practically demolished the edifice of capitalism. One felt like an Aunt Sally under his attacks (the poor old Guinness trustee, Mr Bland, could stand it no more, and I saw him leave the gallery) blow after blow; increased surtax; lower allowances; raised duties on wine, cigarettes and sugar; substantially increased death duties. It is all so bad that one can only make the best of it, and re-organise one's life accordingly.

(2) Winston Churchill, memorandum (6th November, 1941)

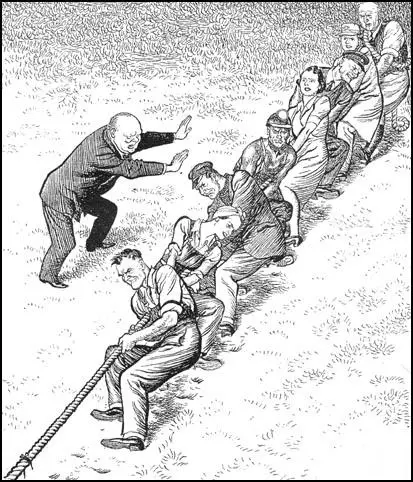

Besides manning the forces, heavier demands were now put forward on behalf of the expanding munitions factories and workshops. If the country's morale was to be sustained the civil population must also be well nourished. Mr. Bevin at the Ministry of Labour and National Service used all his knowledge and influence as an experienced trade union leader to gather the numbers required. It was already obvious that man-power was the measure alike of our military and economic resources. Mr. Bevin, as the supplier of labour, and Sir John Anderson, Lord President of the Council, together devised a system which served us in good stead up to the end of the war, and enabled us to mobilise for war work at home or in the field a larger proportion of our men and women than any other country of the world in this or any previous war. At first the task was to transfer people from the less essential occupations. As the reservoir of manpower fell all demands had to be cut. The Lord President and his Manpower Committee adjudicated, not without friction, between competing claims. The results were submitted to me and the War Cabinet.

(3) Thomas Pynchon, The Road to 1984, The Guardian (3rd May, 2003)

One could certainly argue that Churchill's war cabinet had behaved on occasion no differently from a fascist regime, censoring news, controlling wages and prices, restricting travel, subordinating civil liberties to self-defined wartime necessity.

(4) The East Grinstead Observer (16th September, 1944)

Christopher Bates, 1 Balls Green, Withyham, was sent to prison for 21 days by East Grinstead Magistrates on Monday for refusing to work down the coal mines as directed. The defendant stated that he had suffered from pains in the head, and had a fear of going underground. He stated he was a keen member of the Home Guard and had volunteered for the Royal Navy but had not been called up.

(5) The East Grinstead Observer (11th November, 1944)

Thomas Lower, aged 18, of Grantham Cottages, Copthorne, pleaded guilty at East Grinstead Magistrates Court on Monday for not reporting for training in the coal mines. When interviewed. Lower said: "I will go into any of the Forces but not the mines. I would rather go to gaol." Mr. A. J. Burt, told Lower that coal mining was as valuable a service as entering the Forces and it was in the nation's interest that the defendant should obey the directives of the government.