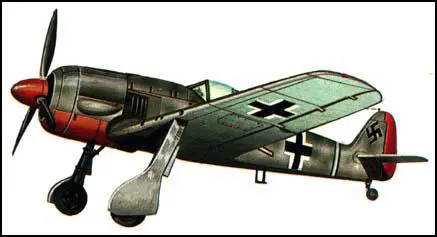

Focke Wulf 190A

In the autumn of 1937 the German Air Ministry decided it needed another fighter aircraft to supplement the Messerschmitt Bf109. The design team was headed by Kurt Tank, the technical director of Focke Wulf Flugzeugbau. The Focke Wulf 190 flew for the first time on 1st June, 1939, but technical problems meant that it did not become fully operational until July, 1941.

The Focke Wulf 190 had a maximum speed of 389 mph (626 km) and had a range of 497 miles (800 km). It was 29 ft 9 in (8.84 m) long with a wingspan of 34 ft 5 in (10.50 m). The aircraft was armed with 4 machine-guns and two 20 mm cannons.

The Focke Wulf 190 was superior to the Messerschmitt Bf109 and for the rest of the Second World War was the best fighter plane in the Luftwaffe. A total of 13,367 were built during the war. Even RAF pilots accepted that because of its speed and ease of handling it outperformed the Supermarine Spitfire.

Primary Sources

(1) Douglas Bader wrote about the Focke-Wulf 190 in his autobiography, Fight for the Sky (1974)

The Focke-Wulf 190 certainly gave the British a shock. 1941 had ended with the Me 109 with the Spitfire (two cannons and four machine-guns fighting it out on fairly even terms. Then, without warning from British intelligence sources, this startling aeroplane appeared in March 1942. A radial-engineered fighter, it out-climbed and out-dived the Spitfire. Now for the first time the Germans were out-flying our pilots. Instantly Rolls and Supermarine retaliated with the Spitfire IXa which equalled the 190, followed at the spring of 1942 with the IXa which equalled the 190, followed at the end of 1942 with the IXb which outflew it in all respects. The Spitfire was unchallenged for the rest of the war, except in the last few months by the Messerschmitt 262 jet which arrived too late to make a significant contribution.

(2) Winston Churchill, directive to his military commanders (6th March, 1941)

We must take the offensive against the U-boat and the Focke-Wulf wherever we can and whenever we can. The U-boat at sea must be hunted, the U-boat in the building yard or in the dock must be bombed. The Focke-Wulf and other bombers employed against our shipping must be attacked in the air and in their nests.

(3) After the war the British fighter pilot Johnnie Johnson wrote about the merits of the Focke-Wulf 190.

The Focke-Wulf 190 was undoubtedly, the best German fighter. We were puzzled by the unfamiliar silhouette, for these new German fighters seemed to have squarer wingtips and more tapering fuselages than the Messerschmitts we usually encountered. We saw that the new aircraft had radial engines and a mixed armament of cannons and machine-guns, all firing from wing positions.

Whatever these strange fighters were, they gave us a hard time of it. They seemed to be faster in a zoom climb than the Me 109, and far more stable in a vertical dive. They also turned better. The first time we saw them we all had our work cut out to shake them off, and we lost several pilots.

Back at our fighter base and encouraged by our enthusiastic Intelligence Officers, we drew sketches and side views of this strange new aeroplane. We were all agreed that it was superior to the Me 109f and completely outclassed our Spitfire Vs. Our sketches disappeared into mysterious Intelligence channels and we heard no more of the matter,. But from then on, fighter pilots continually reported increasing numbers of these outstanding fighters over northern France.

(4) Alan Deere, Nine Lives (1959)

Savagely I hauled my reluctant Spitfire around to meet this new attack and the next moment I was engulfed in enemy fighters-above, below and on both sides, they crowded in on my section. Ahead and above, I caught a glimpse of a FW 190 as it poured cannon shells into the belly of an unsuspecting Spitfire. For a brief second the Spitfire seemed to stop in mid-air, and the next instant it folded inwards and broke in two, the two pieces plummeting earthwards; a terrifying demonstration of the punch of the FW 190s, four cannons and two machine-guns.

I twisted and turned my aircraft in an endeavour to avoid being jumped and at the same time to get myself into a favourable position for attack. Never had I seen the Huns stay and fight it out as these Focke-Wulf pilots were doing. In Messerschmitt 109s the Hun tactics had always followed the same pattern-a quick pass and away, sound tactics against Spitfires with their superior turning circle. Not so these FW 190 pilots, they were full of confidence.

There was no lack of targets, but precious few Spitfires to take them on. I could see my number two, Sergeant Murphy, still hanging grimly to my tail but it was impossible to tell how many Spitfires were in the area, or how many had survived the unexpected onslaught which had developed from both sides as the squadron turned to meet the threat from the rear. Break followed attack, attack followed break, and all the time the determined Murphy hung to my tail until finally, when I was just about short of ammunition and pumping what was left at a FW 190, I heard him call:

"Break right, Red One; I'll get him."

As I broke, I saw Murphy pull up after a FW 190 as it veered away from me, thwarted in its attack by his prompt action. My ammunition expended, I sought a means of retreat from a sky still generously sprinkled with hostile enemy fighters, but no Spitfires that I could see. In a series of turns and dives I made my way out until I was clear of the coast, and diving full throttle I headed for home.

(5) Pierre Clostermann, Flames in the Sky (1957)

Red tracers danced past my windshield and suddenly I saw my first Hun! I identified it at once-it was a Focke-Wulf 190. I had not studied the photos and recognition charts so often for nothing.

After firing a burst of tracer at me he bore down on Martell. Yes, it certainly was one-the short wings, the

radial engine, the long transparent hood: the square-cut tail-plane all in one piece! But what had been missing from the photos was the lively colouring-the pale yellow body, the greyish green back, the big black crosses outlined in white. The photos gave no hint of the quivering of the wings, the outline elongated and fined down by the speed, the curious nose-down flying attitude.