Henry "Box" Brown

Henry Brown was born into slavery in Louisa County, Virginia, in 1815. When he was 15 years old he was sold to a plantation owner in Richmond. He later recalled: "My father and mother were left on the plantation; but I was taken to the city of Richmond, to work in a tobacco manufactory, owned by my old master's son William, who had received a special charge from his father to take good care of me, and which charge my new master endeavoured to perform."

The Nat Turner Rebellion took place in 1831 in neighbouring Southampton County. Brown later explained the impact that this had on the slaves on his plantation: "About eighteen months after I came to the city of Richmond, an extraordinary occurrence took place which caused great excitement all over the town. I did not then know precisely what was the cause of this excitement, for I could got no satisfactory information from my master, only he said that some of the slaves had plotted to kill their owners. I have since learned that it was the famous Nat Turner's insurrection. Many slaves were whipped, hung, and cut down with the swords in the streets; and some that were found away from their quarters after dark, were shot; the whole city was in the utmost excitement, and the whites seemed terrified beyond measure. Great numbers of slaves were loaded with irons; some were half hung as it was termed - that is they were suspended from some tree with a rope about their necks, so adjusted as not quite to strangle them - and then they were pelted by men and boys with rotten eggs."

Brown met another slave, Nancy, who he wanted to marry. "I now began to think of entering the matrimonial state; and with that view I had formed an acquaintance with a young woman named Nancy, who was a slave belonging to a Mr. Leigh a clerk in the Bank, and, like many more slave-holders, professing to be a very pious man. We had made it up to get married, but it was necessary in the first place, to obtain our masters' permission, as we could do nothing without their consent. I therefore went to Mr. Leigh, and made known to him my wishes, when he told me he never meant to sell Nancy, and if my master would agree never to sell me, I might marry her. He promised faithfully that he would not sell her, and pretended to entertain an extreme horror of separating families. He gave me a note to my master, and after they had discussed the matter over, I was allowed to marry the object of my choice." Over the next few years Nancy gave birth to three children.

Slavery in the United States (£1.29)

In 1848 Nancy and her three children were sold to a slave trader who sent them to North Carolina. Brown later recalled: "I had not been many hours at my work, when I was informed that my wife and children were taken from their home, sent to the auction mart and sold, and then lay in prison ready to start away the next day for North Carolina with the man who had purchased them. I cannot express, in language, what were my feelings on this occasion. I received a message, that if I wished to see my wife and children, and bid them the last farewell, I could do so, by taking my stand on the street where they were all to pass on their way for North Carolina. I quickly availed myself of this information, and placed myself by the side of a street, and soon had the melancholy satisfaction of witnessing the approach of a gang of slaves, amounting to three hundred and fifty in number, marching under the direction of a Methodist minister, by whom they were purchased, and amongst which slaves were my wife and children."

The following year Brown, with the help of Samuel Smith, a store-keeper in Richmond, decided to try and escape. "I then told him my circumstances in regard to my master, having to pay him 25 dollars per month, and yet that he refused to assist me in saving my wife from being sold and taken away to the South, where I should never see her again. I told him this took place about five months ago, and I had been meditating my escape from slavery since, and asked him, as no person was near us, if he could give me any information about how I should proceed. I told him I had a little money and if he would assist me I would pay him for so doing."

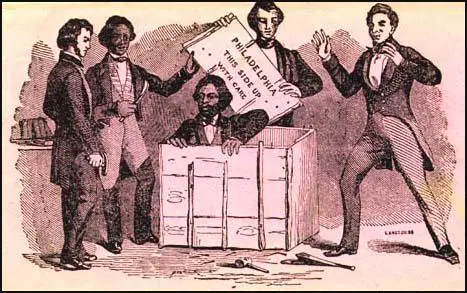

The two men devised a plan where the slave would be shipped to a free state by Adams Express Company. Brown paid $86 to Smith, who contacted the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee, who agreed to receive the box. Smith sent the box to Philadelphia on 23rd March, 1849. According to one account "Brown's box traveled by wagon, railroad, steamboat, wagon again, railroad, ferry, railroad, and finally delivery wagon. Several times during the 27-hour journey, carriers placed the box upside-down or handled it roughly, but Brown was able to remain still enough to avoid detection." The box containing Brown was received by William Still and James Miller McKim.

Henry "Box" Brown became active in the Anti-Slavery Society and became one of their most important speakers. In 1849 he published Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown. After the passing of Fugitive Slave Law Brown moved to England. A second edition of his autobiography was published in Manchester in 1851.

Over the next ten years he made speeches all over Britain. Samuel Fielden was one of those who saw him when he visited Todmorden: "There appeared in Todmorden at different times, several colored lecturers who spoke on the slavery question in America. I went frequently to hear them describe the inhumanity of that horrible system, sometimes with my father, and at other times with my sister. One of these gentlemen called himself Henry Box Brown; the gentleman brought with him a panorama, by means of which he described places and incidents in his slave life, and also the means of his escape.... He was a very good speaker and his entertainment was very interesting."

Brown also worked as a conjuror. He married a British woman and in 1875 he returned to the United States. It is not known when he died.

Primary Sources

(1) Henry Box Brown, Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown (1851)

My father and mother were left on the plantation; but I was taken to the city of Richmond, to work in a tobacco manufactory, owned by my old master's son William, who had received a special charge from his father to take good care of me, and which charge my new master endeavoured to perform. He told me if I would behave well he would take good care of me and give me money to spend; he talked so kindly to me that I determined I would exert myself to the utmost to please him, and do just as he wished me in every respect. He furnished me with a new suit of clothes, and gave me money to buy things to send to my mother. One day I overheard him telling the overseer that his father had raised me - that I was a smart boy and that he must never whip me. I tried exceedingly hard to perform what I thought was my duty, and escaped the lash almost entirely, although I often thought the overseer would have liked to have given me a whipping, but my master's orders, which he dared not altogether to set aside, were my defence; so under these circumstances my lot was comparatively easy.

Our overseer at that time was a coloured man, whose name was Wilson Gregory; he was generally considered a shrewd and sensible man, and, after the orders which my master gave him concerning me, he used to treat me very kindly indeed, and gave me board and lodgings in his own house. Gregory acted as book-keeper also to my master, and was much in favour with the merchants of the city and all who knew him; he instructed me how to judge of the qualities of tobacco, and with the view of making me a more proficient judge of that article, he advised me to learn to chew and to smoke which I therefore did.

(x) Henry Box Brown, Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown (1851)

About this time Wilson Gregory, who was our overseer, died, and his place was supplied by a man named Stephen Bennett, who had a wooden leg; and who used to creep up behind the slaves to hear what they had to talk about in his absence; but his wooden leg generally betrayed him by coming into contact with something which would make a noise, and that would call the attention of the slaves to what he was about. He was a very mean man in all his ways, and was very much disliked by the slaves. He used to whip them, often, in a shameful manner. On one occasion I saw him take a slave, whose name was Pinkney, and make him take him off his shirt; he then tied his hands and gave him one hundred lashes on his bare back; and all this, because he lacked three pounds of his task, which was valued at six cents.

(2) Henry Box Brown, Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown (1851)

About eighteen months after I came to the city of Richmond, an extraordinary occurrence took place which caused great excitement all over the town. I did not then know precisely what was the cause of this excitement, for I could got no satisfactory information from my master, only he said that some of the slaves had plotted to kill their owners. I have since learned that it was the famous Nat Turner's insurrection. Many slaves were whipped, hung, and cut down with the swords in the streets; and some that were found away from their quarters after dark, were shot; the whole city was in the utmost excitement, and the whites seemed terrified beyond measure. Great numbers of slaves were loaded with irons; some were half hung as it was termed - that is they were suspended from some tree with a rope about their necks, so adjusted as not quite to strangle them - and then they were pelted by men and boys with rotten eggs. This half-hanging is a refined species of punishment peculiar to slaves! This insurrection took place some distance from the city, and was the occasion of the enacting of that law by which more than five slaves were forbidden to meet together unless they were at work; and also of that, for the silencing all coloured preachers.

(3) Henry Box Brown, Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown (1851)

The name of our new overseer was John F. Allen, he was a thorough-going villain in all his modes of doing business; he was a savage looking sort of man; always apparently ready for any work of barbarity or cruelty to which the most depraved despot might call him. As a specimen of Allen's cruelty I will mention the revolting case of a coloured man, who was frequently in the habit of singing. This man was taken sick, and although he had not made his appearance at the factory for two or three days, no notice was taken of him; no medicine was provided nor was there any physician employed to heal him. At the end of that time Allen ordered three men to go to the house of the invalid and fetch him to the factory; and of course, in a little while the sick man appeared; so feeble was he however from disease, that he was scarcely able to stand. Allen, notwithstanding, desired him to be stripped and his hands tied behind him; he was then tied to a large post and questioned about his singing; Allen told him that his singing consumed too much time, and that it hurt him very much, but that he was going to give him some medicine that would cure him; the poor trembling man made no reply and immediately the pious overseer Allen, for no other crime than sickness, inflicted two-hundred lashes upon his bare back.

(3) Henry Box Brown, Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown (1851)

I now began to think of entering the matrimonial state; and with that view I had formed an acquaintance with a young woman named Nancy, who was a slave belonging to a Mr. Leigh a clerk in the Bank, and, like many more slave-holders, professing to be a very pious man. We had made it up to get married, but it was necessary in the first place, to obtain our masters' permission, as we could do nothing without their consent. I therefore went to Mr. Leigh, and made known to him my wishes, when he told me he never meant to sell Nancy, and if my master would agree never to sell me, I might marry her. He promised faithfully that he would not sell her, and pretended to entertain an extreme horror of separating families. He gave me a note to my master, and after they had discussed the matter over, I was allowed to marry the object of my choice.

When Nancy became my wife she was living with a Mr. Reeves, a minister of the gospel, who had not long come from the north, where he had the character of being an anti-slavery man; but he had not been long in the south when all his anti-slavery notions vanished and he became a staunch advocate of slave-holding doctrines, and even wrote articles in favour of slavery which were published in the Richmond Republican.

My wife was still the property of Mr. Leigh and, from the apparent sincerity of his promises to us, we felt confident that he would not separate us. We had not, however, been married above twelve months, when his conscientious scruples vanished, and he sold my wife to a Mr. Joseph H. Colquitt, a saddler, living in the city of Richmond, and a member of Dr. Plummer's church there. This Mr. Colquitt was an exceedingly cruel man, and he had a wife who was, if possible, still more cruel. She was very contrary and hard to be pleased she used to abuse my wife very much, not because she did not do her duty, but because, it was said, her manners were too refined for a slave. At this time my wife had a child and this vexed Mrs. Colquitt very much; she could not bear to see her nursing her baby and used to wish some great calamity to happen to my wife.

Eventually she was so much displeased with my wife that she induced Mr. Colquitt to sell her to one Philip M. Tabb, for the sum of 450 dollars; but coming to see the value of her more clearly after she tried to do without her, she could not rest till she got Mr. Colquitt to repurchase her from Mr. Tabb, which he did in about four months after he had sold her, for 500 dollars, being 50 more than he had sold her for.

(5) Henry Box Brown, Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown (1851)

I had not been many hours at my work, when I was informed that my wife and children were taken from their home, sent to the auction mart and sold, and then lay in prison ready to start away the next day for North Carolina with the man who had purchased them. I cannot express, in language, what were my feelings on this occasion.

I received a message, that if I wished to see my wife and children, and bid them the last farewell, I could do so, by taking my stand on the street where they were all to pass on their way for North Carolina. I quickly availed myself of this information, and placed myself by the side of a street, and soon had the melancholy satisfaction of witnessing the approach of a gang of slaves, amounting to three hundred and fifty in number, marching under the direction of a Methodist minister, by whom they were purchased, and amongst which slaves were my wife and children.

I stood in the midst of many who, like myself, were mourning the loss of friends and relations and had come there to obtain one parting look at those whose company they but a short time before had imagined they should always enjoy, but who were, without any regard to their own wills, now driven by the tyrant's voice and the smart of the whip on their way to another scene of toil, and, to them, another land of sorrow in a far off southern country.

These beings were marched with ropes about their necks, and staples on their arms, and, although in that respect the scene was no very novel one to me, yet the peculiarity of my own circumstances made it assume the appearance of unusual horror. This train of beings was accompanied by a number of waggons loaded with little children of many different families, which as they appeared rent the air with their shrieks and cries and vain endeavors to resist the separation which was thus forced upon them, and the cords with which they were thus bound; but what should I now see in the very foremost waggon but a little child looking towards me and pitifully calling, father! father! This was my eldest child, and I was obliged to look upon it for the last time that I should, perhaps, ever see it again in life; if it had been going to the grave and this gloomy procession had been about to return its body to the dust from whence it sprang, whence its soul had taken its departure for the land of spirits, my grief would have been nothing in comparison to what I then felt; for then I could have reflected that its sufferings were over and that it would never again require nor look for a father's care.

(6) Henry Box Brown, Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown (1851)

I was well acquainted with a store-keeper in the city of Richmond, from whom I used to purchase my provisions; and having formed a favourable opinion of his integrity, one day in the course of a little conversation with him, I said to him if I were free I would be able to do business such as he was doing; he then told me that my occupation (a tobacconist) was a money-making one, and if I were free I had no need to change for another. I then told him my circumstances in regard to my master, having to pay him 25 dollars per month, and yet that he refused to assist me in saving my wife from being sold and taken away to the South, where I should never see her again. I told him this took place about five months ago, and I had been meditating my escape from slavery since, and asked him, as no person was near us, if he could give me any information about how I should proceed. I told him I had a little money and if he would assist me I would pay him for so doing.

The man asked me if I was not afraid to speak that way to him; I said no, for I imagined he believed that every man had a right to liberty. He said I was quite right, and asked me how much money I would give him if he would assist me to get away. I told him that I had $I66 and that I would give him the half; so we ultimately agreed that I should have his service in the attempt for $86. Now I only wanted to fix upon a plan. He told me of several plans by which others had managed to effect their escape, but none of them exactly suited my taste.

One day, while I was at work when the idea suddenly flashed across my mind of shutting myself up in a box, and getting myself conveyed as dry goods to a free state.

(1) Samuel Fielden, Autobiography of Samuel Fielden (1887)

There appeared in Todmorden at different times, several colored lecturers who spoke on the slavery question in America. I went frequently to hear them describe the inhumanity of that horrible system, sometimes with my father, and at other times with my sister. One of these gentlemen called himself Henry Box Brown; the gentleman brought with him a panorama, by means of which he described places and incidents in his slave life, and also the means of his escape. He claimed that he had been boxed up in a large box in which were stowed an amount of provisions, the box having holes bored in the top for air, and marked, "this side up with care." This he was shipped to Philadelphia via the underground railroad, to friends there, and this was why he called himself Henry Box Brown. He was a very good speaker and his entertainment was very interesting.