Jake Lingle

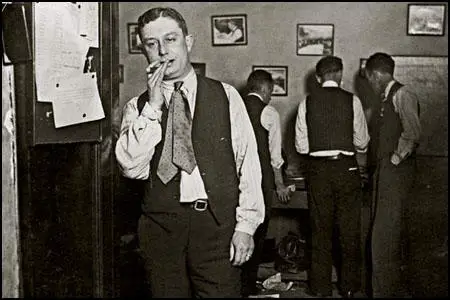

Alfred "Jake" Lingle was born on 2nd July, 1891. He became a journalist on the Chicago Tribune. It was claimed by other reporters that Lingle was close to Al Capone, the Police Commissioner William F. Russell, Governor Louis Lincoln Emmerson and Arthur W. Cutten, the millionaire Chicago trader.

As Richard Babcock has pointed out: "Jake Lingle, however, was no ordinary reporter. He operated at the center of a network of friends and associates that may stand unmatched for its depth and width in the history of the grown-up city. His best friend was William Russell, the chief of police, yet Lingle talked regularly with Al Capone and other gangsters, conversations that produced countless scoops for the Tribune. He hobnobbed with Governor Louis Emmerson and collected tips on investments from Arthur Cutten, the millionaire Chicago trader. Politicians, prosecutors, judges, cops, and athletes all offered confidences to the 38-year-old reporter, but his network stretched far beyond the well connected."

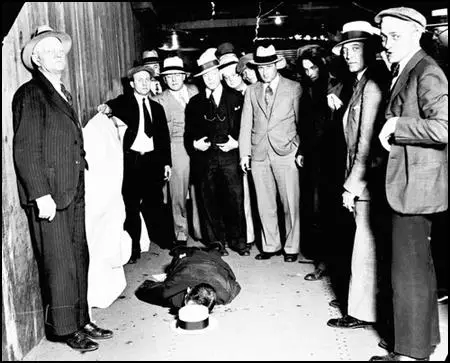

Lingle was shot dead was shot by a gunman in the pedestrian tunnel of the Illinois Central Railroad's suburban service off Michigan Avenue at Randolph Street on 9th June, 1930. Soon afterwards Leo Vincent Brothers was arrested and charged with Lingle's murder. At first it was believed that Lingle was killed because he was working on an important crime story. However, journists on the newspaper knew this was not the case. A colleague, John O'Brien, later reported: "In the aftermath of his shooting, Chicago newspapers decried the slaying as a mob attempt to silence the press. But as the reporter's mysterious private life came to light, a different picture developed. He was paid $65 a week but had an annual income of $60,000. When he was killed, he had $1,400 in his pocket." Journalists were unable to discover who was paying him this money, but it was possible to trace several expensive gifts back to gang bosses such as Al Capone.

As fellow crime reporter, Walter Trohan, pointed out: "Jake Lingle was shot by Leo V. Brothers, a St. Louis hoodlum, imported to do the job for the North Side gang, known as the Aieilo-Zuta-Moran mob after its more important figures. These gangsters suspected Lingle was taking advantage of his long friendship with Police Commissioner William F. Russell to raid and close their gambling establishments in order to help Capone advance and extend his gambling empire. Lingle, who was never more than a legman, cultivated a mysterious manner, which could be taken as proof of such suspicions and of rumors which, even in his lifetime, reported he was profiting from questionable connections."

Leo Vincent Brothers was found guilty and sentenced to 14 years in prison. However, the author of Egan's Rats: The Untold Story of the Prohibition-Era Gang that ran St. Louis (2007) believes that the real triggerman was Frankie Foster and the contract was handed out and organized by Jake Zuta.

Primary Sources

(1) Walter Trohan, Political Animals: Memoirs of a Sentimental Cynic (1975)

In these early days McCormick was a dim and distant figure in his twenty-fourth-floor office. Yet, his spirit was in the local room at all times, He was known affectionately as "the Colonel," but not without a tinge of awe and even fear. He was an admirable boss, because he was convinced, or at least convinced those in the vine-yard, that every employee with whom he dealt was the best possible man in his post. He was demanding and exacting, but he was also forgiving; he seemed to enjoy the making of mistakes by those about him, so that he could be forgiving...

The colonel seldom appeared in the local room until after Alfred (Jake) Lingle, a Tribune crime reporter, who was reputed to be an intimate of Capone and other gangland figures, was shot by a gunman in the pedestrian tunnel of the Illinois Central Railroad's suburban service off Michigan Avenue at Randolph Street. The slaying precipitated a violent exposure of municipal and county misgovernment that reached into newspaper offices and tarnished some reporters and editors. I have no intention of dwelling on it, except that the case was to be one of my stepping stones to Washington.

Jake Lingle was shot by Leo V. Brothers, a St. Louis hoodlum, imported to do the job for the North Side gang, known as the Aieilo-Zuta-Moran mob after its more important figures. These gangsters suspected Lingle was taking advantage of his long friendship with Police Commissioner William F. Russell to raid and close their gambling establishments in order to help Capone advance and extend his gambling empire. Lingle, who was never more than a legman, cultivated a mysterious manner, which could be taken as proof of such suspicions and of rumors which, even in his lifetime, reported he was profiting from questionable connections.

Colonel McCormick began frequenting the local room. Now and then he would make a speech, which was aimed at restoring confidence, and he would talk over coverage of major stories, asking me to fill him in on such things as bank failures and the political manipulation of Cermak, who had become mayor.

(3) John O'Brien, Chicago Tribune (9th June, 1930)

Alfred "Jake" Lingle was part of the crowd that filled the pedestrian walkway underneath Michigan Avenue on the afternoon of this late spring day.

Lingle, a Tribune police reporter, was heading for the Illinois Central station at Randolph Street to catch the 1:30 p.m. express to Washington Park racetrack in south suburban Homewood. An ace at covering sensational crime stories, he was about to become one.A tall, blond man walked up behind him and put a bullet through his head. Lingle's killer paused over the body. Then he dropped the murder weapon, a .38-caliber revolver, and got away.

Lingle epitomized the "Front Page" journalism of his day, cavorting with cops and robbers and working his sources in speakeasies. A street reporter, he never rolled paper through a typewriter.

As in the Ben Hecht-Charles MacArthur play about Chicago journalism, Lingle phoned in scoops to rewritemen. The popular play was a work of fiction, but it was based on fact. The world of Chicago newspapers was viciously competitive, frequently unscrupulous, and not too worried about the truth.

But even in that era, Lingle turned out to be exceptional. In the aftermath of his shooting, Chicago newspapers decried the slaying as a mob attempt to silence the press.

But as the reporter's mysterious private life came to light, a different picture developed. He was paid $65 a week but had an annual income of $60,000. When he was killed, he had $1,400 in his pocket.

(2) Richard Babcock, Chicago Magazine (November, 2009)

Jake Lingle, however, was no ordinary reporter. He operated at the center of a network of friends and associates that may stand unmatched for its depth and width in the history of the grown-up city. His best friend was William Russell, the chief of police, yet Lingle talked regularly with Al Capone and other gangsters, conversations that produced countless scoops for the Tribune. He hobnobbed with Governor Louis Emmerson and collected tips on investments from Arthur Cutten, the millionaire Chicago trader. Politicians, prosecutors, judges, cops, and athletes all offered confidences to the 38-year-old reporter, but his network stretched far beyond the well connected. Years later, Levering Cartwright, a Tribune colleague, recalled being sent with Lingle on an assignment to Chinatown. “He knew every rat hole down there,” Cartwright said. “We’d go into the cellar and there’d be Chinamen playing dominoes or whatever it was, he knew them by their first names. A truck would come along with a Racing Form, and he knew the driver and would get a copy.”

But on that Chicago evening in 1930, Jake Lingle didn’t join the 2,450 bigwigs who dined on filet of Colorado mountain trout, saute meunière, in the grand ballroom at the Stevens, while listening to speakers toast the new LaSalle Street temple of capitalism and decry the “parlor socialists” undermining the country. Earlier that day, as the reporter ambled through a pedestrian tunnel at Michigan Avenue and Randolph Street, a tall young man had walked up and fired a fatal shot into the back of Jake Lingle’s head.

The murder of Jake Lingle, which had all the markings of a mob hit, set off an impassioned outcry in Chicago and across the country. It was one thing when the mobsters shot up each other, but now they had taken out a man “whose business was to expose the work of the killers,” as the Tribune put it. “People started to think it could happen to anyone,” says Tim Samuelson, the cultural historian for the city of Chicago. The furious city “went berserk,” as the investigative reporter Edward Dean Sullivan wrote at the time. Preachers, politicians, businessmen, editorialists, civic groups - all rose up and demanded action against the underworld.

And then, within a week or so, the slow drip of rumor broke into a torrent of news - Lingle was corrupt to his core. The exact levers of his graft remain unclear to this day, but it’s likely he acted as a middleman among mobsters, cops, and politicians, brokering deals to allow illegal operations - speakeasies, gambling joints, dog tracks - to operate freely. Astonishingly, no one at the Tribune had called him out for being crooked, even though he lived and spent extravagantly on his lowly newsman’s salary, and even though he paraded around wearing a diamond-studded belt buckle, a gift from Capone himself.