The Dark Ages and Alfred the Great

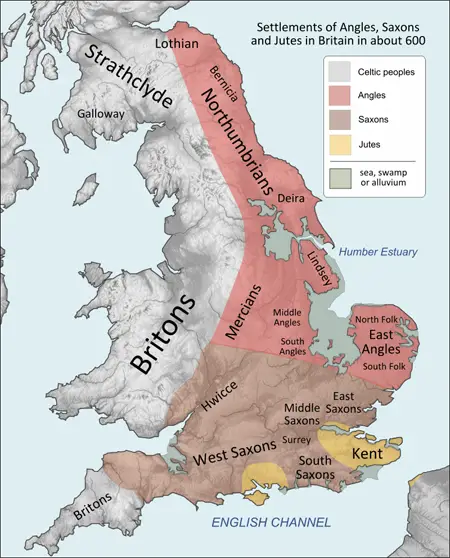

Centralized government that was introduced by the Romans disappeared within a few years. Over the next couple of hundred years new people arrived on the island. This included tribes from Germany (Angles and Saxons) and France (Franks and Jutes). They joined the Celts who had been here before the Romans arrived. Scandinavian tribes also carried out attacks on coastal areas and sometimes settled in Britain.

In about 575 a monk called Gregory saw some young men in the Rome slave-market. He spoke to them and discovered that these men were from England. After talking to these slaves he was shocked to discover that there were very few Christians living in England. Gregory was determined to change this situation and when he became Pope he sent his friend Augustine and forty monks to England to convert the inhabitants to Christianity. (1)

Augustine arrived in England in 597. He made his way to Canterbury, the home of Ethelbert, the king of Kent. Within a few weeks Augustine had converted Ethelbert and most of his household to Christianity. Pleased by his success, the following year Pope Gregory appointed Augustine as Bishop of Canterbury, and Archbishop of the English people. In 604, Augustine founded two more bishoprics in Britain. Two men who had come to Britain with him in 601 were consecrated, Mellitus as Bishop of London and Justus as Bishop of Rochester. Christian missionaries who went into the north had more difficulty in converting tribal leaders and it was not until 735 that Ecgbert was created Archbishop of York. (2)

This period is known as the Dark Ages because there are very few written records of the people who lived in Britain during this period. One of the main written sources available to us is from Bede, a monk from Durham. Bede was born near Monkwearmouth, in about 673. At the age of seven he was placed in the care of Benedict Biscop at Wearmouth Monastery. Bede used Biscop's library to study Latin, Greek and Hebrew. Over the next thirty years he wrote extensively about a wide-range of subjects including religion, medicine, astronomy, language and physical science. Bede's greatest work was the Ecclesiastical History of the English People, which he finished in 731. The book is the most valuable source that we have for early English history. (3)

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle are a collection of seven manuscripts written by monks living in England between the 9th and 12th centuries. The chronicles, written in Anglo-Saxon (Old English) in the form of a diary, tell the story of England, and cover a period of over a thousand years. In some cases the entries were made several years after the events took place. Some passages in the various manuscripts are identical suggesting that a certain amount of copying took place. There are three main manuscripts. It is believed that Version C was written in Abingdon near Oxford, Version D in Worcester and York, and Version E in Canterbury.

Viking attacks on Wessex

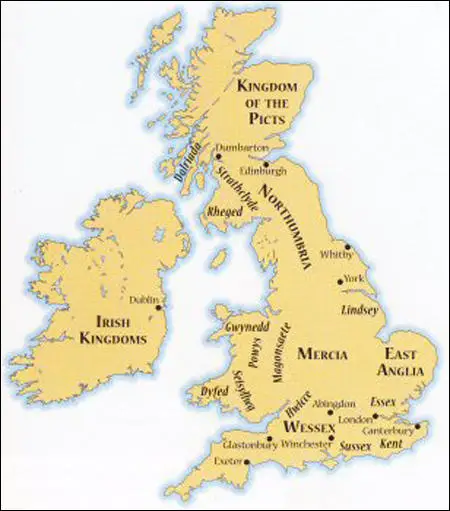

At the beginning of the 9th century Britain was ruled by several kings (chieftains). Kent, Wessex, Northumbria and Mercia were important kingdoms. Religion was for a long time a matter upon which kings decided from policy or conviction and the people followed.

King Ethelwulf of Wessex was a devout Christian and in 852, when his son, Alfred, was four years old he was sent to Rome to meet Pope Leo IV. The historian Douglas Woodruff points out that this was an experience none of his brothers nor any other English king had in early life, and it is perhaps not fanciful to think that the impression Rome made on him accounted for the quite exceptional devotion to learning as well as to religion that was to mark him in his maturity." (4) Alfred experienced poor health as a child. According to John Assler he had these problems "from the first flowering of his youth" and it was feared that he would die before reaching adulthood. (5) A doctor who has studied his symptoms has suggested that he was suffering from tuberculosis or/and Crohn's disease. (6)

In 856 Ethelwulf visited Rome for the first time. Alfred went with him and he left two of his sons, Ethelbald and Ethelberht to rule Wessex while he was away. Ethelbald became very angry when he heard that his father had married Judith of Flanders, the daughter of Charles the Bald, the king of Italy. Ethelbald was concerned that she might "produce heirs more throne-worthy than he". (7)

Ethelwulf died eleven months after his return from Italy. Ethelbald now became king of Wessex. He also married his father's young widow, Judith. This caused a great scandal as this was forbidden by the Church. Ethelbald only survived his father by only a little over three years and died on 20th December 860. (8) John Assler described Ethelbald as "iniquitous and grasping", and his reign as "two and a half lawless years". (9)

Ethelberht replaced his brother as king. As well as Wessex he also became king of Kent. During this period Alfred lived at East Dene and according to one biographer, spent a good deal of time in Alfriston. (10) The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes his reign as one of good harmony and great peace. Although this was true of internal affairs, the Vikings remained a threat, unsuccessfully storming Winchester and ravaging all eastern Kent. Ethelberht died in the autumn of 865 and was buried at Sherborne beside his brother Ethelbald. (11)

Ethelred, who was only aged eighteen, became the next king of Wessex. In 868 Alfred married Ealhswith, daughter of a Mercian nobleman. They had five or six children together, including Edward the Elder, Ethelweard, Ethelflaed (who married Ethelred, the ruler of Mercia) and Elfthryth (who married Baldwin II the Count of Flanders). (12)

The Vikings increased their attacks on England and over the next five years they conquered and installed their own rulers over Northumbria and East Anglia. They also captured Nottingham in Mercia. In 870 they turned their attention to Wessex and set up base at Reading. Alfred joined his brother in battle against the Vikings. A victory at Ashdown was followed by defeat at Basing. (13)

Alfred, King of Wessex

Ethelred was badly wounded in battle and died of his injuries on 15th April, 871. Alfred was now the king of Wessex. "Never before and never since in our history have four brothers succeeded each other on the same throne, and all inside ten years. Ethelbald, Ethelberht and Ethelred were not slain in battle, although they all fought battles, but it is very possible that wounds in battle played their part in cutting short their lives." (14)

Alfred was faced with a serious threat from Scandinavian leaders that included Ivar the Boneless, Björn Ironside, Halfdan Ragnarsson and Sigurd Snake-in-the-Eye. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that these warriors had settled in Northumbria, Mercia and East Anglia. There is also evidence for a Danish and Norwegian presence in Yorkshire and the Lake District. Scandinavians took their paganism seriously, and destroyed a large number of churches in England. (15)

The Vikings had developed new methods of war. The moved fast at sea in their long, many-oared ships carrying up to 100 men apiece, and on the land by rounding up all the horses where ever they touched and turning themselves into the first mounted infantry. They also learnt to build strong, stockaded forts, and when defeated retired behind these and were able to resist attacks from the British tribes. (16)

Guthrum, a Danish chieftain, became a serious problem for Alfred with his army raiding Wessex. Alfred confronted him in a series of skirmishes but Guthrum's hopes of conquering all of Wessex came to an end with the Battle of Edington in May 878. The Danes were pursued to Chippenham and was besieged for ten days, until agreeing to surrender. Under the Treaty of Wedmore the borders dividing the lands of Alfred and Guthrum were established. (17)

To show his good will, Guthrum converted to Christianity and took on the Christian name Ethelstan with Alfred as his godfather. (18) As the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle pointed out: "Then the raiding army granted him (Alfred) hostages and great oaths that they would leave his kingdom and also promised him that their king (Guthrum) would receive baptism; and they fulfilled it. And three weeks later the king Guthrum came to him, one of thirty of the most honourable men who were in the raiding army, at Aller - and that is near Athelney - and the king received him at baptism; and his chrism loosing was at Wedmore." (19)

Guthrum upheld his end of the treaty and left Alfred's territory unmolested. According to Douglas Woodruff, the author of Alfred the Great (1974) argued: "Alfred himself, the respect the Danes could not withhold from him as a fighting man, the magnanimity of his spirit, and his deep personal conviction of the truths of Christianity, which made a lasting impression on Guthrum, putting him in a class apart from the other Danish leaders. He kept his pact with Alfred, and it was no doubt by agreement that after a year at Cirencester he moved his army into East Anglia, and began settling them on the land." (20)

Alfred also took control of Mercia, including London, its capital, in 886. Some of his charters now called him "king of the Anglo-Saxons". Assler described Alfred as "ruler of all Christians of the island of Britain" and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle asserts of Alfred that all the people "except what was under subjection to the Danes submitted to him". (21) David Pratt points out that although almost all chroniclers agree that the Saxon people of pre-unification England submitted to Alfred, he did not adopt the title King of England himself. (22)

Military and Legal Reforms

Alfred introduced several military reforms. One, reported in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle's annal for 893, was the division of the fyrd into two "so that always half were at home and half on service". In 896, the annal reported that Alfred began to build ships to an enlarged sixty-oar design of his own. This reform resulted in some historians claiming that Alfred was the father of an English navy. The third major reform was "building a chain of forts around his kingdom, from Devon and Somerset to Sussex and Surrey." (23) It has been claimed that "Alfred's defensive arrangements enabled the mass of the people to live and work in peace." (24)

Alfred's close associate, John Assler, explained: "He (Alfred) was a bountiful giver of alms, both to his own countrymen and to foreigners of all nations, incomparably affable and pleasant to all men, and a skilful investigator of the secrets of nature. Many Franks, Frisians, Gauls, Pagans, Britons and Scots, and Bretons submitted voluntarily to his dominion, both noble and ignoble, all of whom, according to their birth and dignity, he ruled, loved, honoured, and enriched with money and power." (25)

Douglas Woodruff has argued that Alfred introduced several important legal reforms. At that time Judgement by Ordeal was a widespread custom among the people of Britain. For example, someone accused of a crime might be made to eat a specially baked cake. It was believed if the person was lying, God would make sure he choked and died.

Ordeal by fire involved the accused plunging his bare arm into boiling water and fetch out a stone from the bottom of the vessel. His arm was then bandaged and left for three days. At the end of the time, priests, in the presence of witnesses, unbandaged the arm and if it was completely healed he would be acquitted. On other occasions a man would have to carry a very hot iron rod for a number of paces. The test of innocence was the burns should disappear in three days.

In about 890, Alfred issued a law code, consisting of his "own" laws followed by a code issued by his predecessor King Ine of Wessex. About a fifth of the law code is taken up by Alfred's introduction. Alfred encouraged the use of local courts where jurors knew something about the person accused of a crime. "The beginnings of the jury system rested on the principle that one of the best guides to who was telling the truth was the good name or the less good name that a man enjoyed among his neighbours. The guiding principle was exactly the opposite of what was later to become the essence of the jury system, that the jurors must have no previous knowledge of the parties to a suit and if possible no knowledge of the facts or preconceived opinions." (26)

Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great surrounded himself with scholars such as John Assler, Grimbald of St Bertin, John the Old Saxon and Plegemund of Mercia. He insisted that all his officials obtain wisdom (learnt to read). According to Patrick Wormald the "idea of wisdom observably drove Alfred's programme of spiritual and cultural revival". Alfred wanted his officials to learn Latin as well as English. (27)

His close adviser, John Assler, supports this view: "Meanwhile amid wars and the frequent hindrances of this present life, the incursions of the Pagans and his own daily infirmities of body, the King did not cease to carry on the government and to engage in hunting of every form; to teach his goldsmiths and all his artificers, his falconers, hawkers and dog-keepers; to erect by his own inventive skill finer and more sumptuous buildings than had ever been the wont of his ancestors; to read aloud Saxon books, and above all, not only to command others to learn Saxon poems by heart but to study them himself in private to the best of his power... Moreover, he loved his bishops and the whole order of clergy, his earls and nobles, and all his servants and friends with wonderful affection, and he looked upon their sons, who were brought up in the royal household, as no less dear to him than his own, never ceasing night and day, among other things, to instruct them in all good morals and to teach them letters." (28)

Alfred the Great introduced a new education system. The emphasis was on a school at court itself rather than in the kingdom's major churches. Children of lesser as well as noble birth were schooled there. "The schooling was to begin in the vernacular, not for its own sake but, as Alfred said, to lay foundations on which Latin learning could then be built in those continuing to higher rank.... The vernacular received such a boost that English now became a language of prose literature, with all that was to mean for its survival." (29)

Alfred decided to translate books into Anglo-Saxon. His first book was Pastoral Care, a treatise on the responsibilities of the clergy, that had been written by Pope Gregory I in about 590. This was followed by

History against the Pagans by Paulus Orosius. This book was written in about 416 and Alfred added a lot of historical information that was not in the original book. He also provided an Anglo-Saxon translation of Ecclesiastical History of the English People, a book that had been produced in Latin by Bede. It is this work that has given him the title of the "father of English prose". (30)

In 892 the Danish commander Haesten sailed to England from Boulogne to the Kent coast. His army landed in 80 ships and occupied the village of Milton Regis, whilst his allies landed at Appledore with 250 ships. Alfred positioned his army between them to keep them from uniting, the result of which was that Haesten agreed terms, including allowing his two sons to be baptised, and left Kent and established a camp at Benfleet. (31)

Hastein used this camp as a base to raid Mercia. Alfred's troops captured his fort, along with his ships, women and children. This included Hastein's own wife and sons. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Hastein negotiated the release of his family. Shortly afterwards, Hastein launched a second raid along the Thames valley and from there along the River Severn. Eventually they returned to the fortress at Shoeburyness. "After many weeks had passed, some of the heathens (Danes) died of hunger, but some, having by then eaten their horses, broke out of the fortress, and joined battle with those who were on the east bank of the river. But, when many thousands of pagans had been slain, and all the others had been put to flight, the Christians were masters of the place of death." (32)

Alfred the Great died on 26th October 899. He was barely fifty. His successor was his son Edward the Elder. It has been claimed by his biographer, Patrick Wormald: "It is needless to endorse all that has been thought of Alfred as history transmuted into myth. The historical record plainly establishes that he was among the most remarkable rulers in the annals of human government." (33)

Edward defeated the the Danes in East Anglia in 902 and gained control of Chester and Oxford. Three years later he defeated the Danes in Northumbria at the Battle of Tettenhall. After this date they never raided south of the River Humber. Edward ordered the construction of a number of fortresses that kept the Danes outside his territory. By the time he died in 924 he controlled more land than his father. (34)

Edward had at least fourteen children and three wives. Three of them became kings of the Anglo Saxons and from 927 king of the English: Ethelstan (924-939), Edmund (939-946) and Eadred (946-955). Alfred's descendants remained in control until the Danish king, Sweyn Forkbeard, invaded in 1013. Over the next 30 years a struggle for power took place between the Anglo-Saxons and the Danes.

The Perfect Character in History

Barbara Yorke has argued that "Alfred’s lack of a saintly epithet, a disadvantage in the high Middle Ages, was the salvation of his reputation in a post-Reformation world. As a pious king with an interest in promoting the use of English, Alfred was an ideal figurehead for the emerging English Protestant church". Archbishop Matthew Parker "did an important service to Alfred’s reputation by publishing an edition of Asser’s Life of Alfred in 1574." (35)

John Foxe, the author of Foxe's Book of Martyrs (1563) also wrote favourably about Alfred. It has been argued that this is one of the most important books published in the English language: "The Book of Martyrs, with the full force of government propaganda behind it, undoubtedly had a powerful effect on the English people, and is one of the few books which can be said to have changed the course of history." (36)

It was during the reign of Queen Victoria, that Alfred really gained his impressive reputation. Joanne Parker, argues in her book, England's Darling: The Victorian Cult of Alfred the Great (2007) that "the Saxon monarch became increasingly promoted as a moral role-model for everyone, and his personal achievements, accomplishments and character were investigated and discussed as much as his civic institutions and establishments." Parker quotes the Victorian historian, Edward Augustus Freeman, the author of The History of the Norman Conquest of England (1867-1879) as describing Alfred as "the most perfect character in history". (37)

Charles Dickens also loved Alfred and in his book A Child’s History of England (1851-53) he puts forward the viewpoint that he was our greatest king: "As great and good in peace, as he was great and good at war, King Alfred never rested from his labours to improve his people. He loved to talk with clever men, and with travellers from foreign countries, and to write down what they told him, for his people to read.... He founded schools; he patiently heard causes himself in his Court of Justice; the great desires of his heart were to do right to all his subjects, and to leave England, better, wiser, happier in all ways, than he found it." (38)

In the 20th century Alfred was acclaimed by Marxist historians. A. L. Morton, the author of A People's History of England (1938) claims that his achievements in the field of education makes him "one of the greatest figures in English history". Morton points out: "Alfred encouraged learned men to come from Europe and even from Wales and in middle age taught himself to read and write in Latin and English... He sought eagerly for the best knowledge that the age afforded and in a less illiterate time would probably have attained a really scientific outlook. Constantly in ill health, never long in peace, the extent of his work is remarkable." (39)