Pompeii

Pompeii was one of the most important cities in the Roman Empire. It was a popular place to live because the nearby Bay of Naples and the River Sarnus provided a good transport system for exporting their goods to other parts of the Roman Empire. Pompeii also had extremely fertile volcanic soil. This soil had been created by the volcano, Mount Vesuvius, that was less than ten kilometres from Pompeii.

On 5 February, AD 62 a serious earthquake hit the Bay of Naples. In Pompeii and the neighbouring city of Herculaneum nearly every building was damaged and many were completely destroyed. The local people believed they must have upset their gods, and those that survived increased their prayers and sacrifices.

The real reason for the earthquake was that steam and gases were building up inside Vesuvius. Unable to find a way through to the surface, an earthquake, rather than a volcanic eruption, took place.

Some people left the area but the vast majority decided to stay. The Roman government gave financial help and within fifteen years the rebuilding of Pompeii and Herculaneum had nearly been completed.

In the summer of AD 79 the people living close to Vesuvius felt several earth tremors. The most serious of these took place on the morning of 24 August. A few hours later the people heard a tremendous explosion. The steam and gases that had been building up for hundreds of years had finally blown out a gigantic hole at the top of Vesuvius. The violence of the eruption blasted rock and ash into the air. So much debris was thrown out that it completely blocked the rays of the sun. Within minutes the whole area was in darkness, the only light coming from the flames shooting from the top of Vesuvius.

The steam that emerged from Vesuvius was extremely hot (an estimated 2000° Fahrenheit). Condensing as it made contact with the atmosphere, the steam turned into heavy rain. This combination of volcanic ash, earth and rain created an avalanche of hot mud. As it flowed down the mountain towards the sea, it destroyed all the houses and villas in its path. At the bottom, four kilometres away, the mud reached Herculaneum. As the mud rose fairly slowly, most people were able to get away before the whole town was completely submerged.

Pompeii, which was on the other side of Vesuvius, did not suffer from mud like Herculaneum. Instead it was showered with lapilli (rock fragments formed by lava spray). At first the situation did not seem as serious as it was in Herculaneum, and people tended to seek protection from the falling lapilli by taking shelter in their houses.

It was not long before the weight of the lapilli on the roofs became so heavy that buildings began to collapse. People now realised they had to abandon Pompeii. For many it was too late. Vesuvius was now belching out sulphur fumes and many were poisoned while trying to flee. Of the 15,000 population, an estimated 2,000 died in the disaster.

Vesuvius continued throwing out lapilli and poisonous fumes for two days. When the rescue parties finally arrived, they discovered that Herculaneum had completely disappeared. At Pompeii, only the tops of high buildings could be seen. Attempts were made by survivors to reach their valuable possessions but it was not long before they accepted defeat and left to live in another area.

Pliny the Elder was commander of the Misenum naval base and died while trying to rescue people living in the Bay of Naples during the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79. Afterwards, Pliny the Younger told Tacitus what had happened: "As he (Pliny the Elder) was leaving the house he was handed a message from Rectina, wife of Cascus, whose house was at the foot of the mountain... She was terrified by the danger threatening her and implored him to rescue her from her fate... He gave orders for the warships to be launched and went on board himself with the intention of bringing help to many more people besides Rectina, for this lovely stretch of coast was thickly populated. He hurried to the place which everyone else was hastily leaving, steering his course straight for the danger zone... Ashes were already falling, hotter and thicker as the ships drew near, followed by bits of pumice and blackened stones, charred and cracked by the flames: then suddenly they were in shallow water, and the shore was blocked by the debris from the mountain... but he was able to bring the ship in (at Stabiae)."

Over the years nature took its course and the pumice stone and the hardened volcanic ash were covered by a layer of earth. Pompeii, was now six metres underground and people forgot about its existence until Count Tuttavilla's workers found it again in 1594. In the years that followed this discovery, rich Italians employed labourers to dig tunnels into the ground so that they could plunder the underground city of its valuable artefacts. It was not until 1860 that an attempt was made to excavate the site in a scientific way.

Giuseppe Fiorelli was put in charge of the operation at Pompeii and his activities dramatically changed attitudes towards archaeology. Fiorelli was mainly concerned with discovering what everyday life was like in an ancient Roman city. Whereas previous archaeologists had spent their time looking for valuable objects, Fiorelli concentrated on excavating the homes and streets of Pompeii.

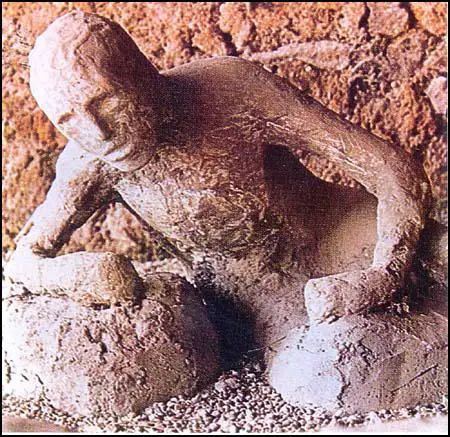

Fiorelli was aware that after nearly 2,000 years the bodies of the people who had died during the eruption of Vesuvius would have rotted away. However, he developed a technique that enabled him to reconstruct the shapes of people who had died. Fiorelli realised that the lava that suffocated the people of Pompeii would have hardened round the corpse. In time, the corpses would have rotted away. By pouring plaster into cavities which this process left, and then chipping away the lava rock, Fiorelli was able to reconstruct the original shape. As well as reconstructing people and animals, Fiorelli was able to reproduce wooden objects such as tables and chairs that had also rotted away since AD 79.

One of the most interesting aspects of Pompeii is the large number of messages written on the walls. While we have many examples of books and letters written by rich and powerful Romans, this graffiti, scratched on walls by iron nails, gives us a good insight into what ordinary people in Pompeii felt about living in the Roman Empire.

Herculaneum was discovered in 1710 by a peasant digging a well. However, it was not until 1927 that the Italian government decided to pay for archaeologists to work at Herculaneum. The result has been spectacular. The reason for this concerns the way Herculaneum was covered during the volcanic eruption. As the liquid mud rose slowly, it often covered objects without damaging them. For example, eggs were covered without the shells being broken. Also the heat of the mud carbonised the objects and preserved them from decay. Some of the buildings and their contents have survived intact and provide an excellent picture of what life was like in the Roman Empire during the first century AD.

Primary Sources

(1) Pliny the Elder was commander of the Misenum naval base and died while trying to rescue people living in the Bay of Naples during the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79. Afterwards, Tacitus, the Roman historian, wrote to the nephew of Pliny the Elder and asked him what had happened. In his reply, Pliny the Younger described the eruption.

It was not clear at that distance from which mountain the cloud was rising (it was afterwards known to be Vesuvius)... In places it looked white, elsewhere blotched and dirty, according to the amount of soil and ashes it carried with it... My uncle ordered a boat to be made ready, telling me I could come with him if I wished. I replied that I preferred to go on with my studies...

As he (Pliny the Elder) was leaving the house he was handed a message from Rectina, wife of Cascus, whose house was at the foot of the mountain... She was terrified by the danger threatening her and implored him to rescue her from her fate... He gave orders for the warships to be launched and went on board himself with the intention of bringing help to many more people besides Rectina, for this lovely stretch of coast was thickly populated.

He hurried to the place which everyone else was hastily leaving, steering his course straight for the danger zone... Ashes were already falling, hotter and thicker as the ships drew near, followed by bits of pumice and blackened stones, charred and cracked by the flames: then suddenly they were in shallow water, and the shore was blocked by the debris from the mountain... but he was able to bring the ship in (at Stabiae). He embraced Pomponianus, his terrified friend, cheered and encouraged him, and thinking he could calm his fears by showing his own composure, gave orders that he was to be carried to the bathroom. After his bath he dined...

Meanwhile on Mount Vesuvius broad sheets of fire and leaping flames blazed at several points, their bright glare emphasised by the darkness of night. My uncle tried to allay the fears of his companions by repeatedly declaring that these were nothing but bonfires left by the peasants in their terror, or else empty houses on fire in the districts they had abandoned.

Then he went to rest and certainly slept, for as he was a stout man his breathing was rather loud and heavy and could be heard by people coming and going outside his door. By this time the courtyard giving access to his room was full of ashes mixed with pumice-stones, so that its level had risen, and if he had stayed in the room any longer he would never have got out... They debated whether to stay indoors or take their chance in the open, for the buildings were now shaking with violent shocks, and seemed to be swaying to and fro as if they were torn from the foundations. Outside, on the other hand, there was the danger of falling pumice-stones... after comparing the risks they chose the latter... As a protection against falling objects they put pillows on their heads tied down with cloths.

Elsewhere there was daylight by this time, but they were still in darkness, blacker and denser than any ordinary night, which they relieved by lighting torches and various kinds of lamps. My uncle decided to go down to the shore and investigate the possibility of any escape by sea, but he found the waves still wild and dangerous... Then the flames and smell of sulphur which gave warning of the approaching fire drove the others to take flight and roused him to stand up. He stood leaning on two slaves and then suddenly collapsed, I imagine because the dense fumes choked his breathing...

When daylight returned on the 26th - two days after the last day he had been seen - his body was found intact and uninjured, still fully clothed and looking more like sleep than death.