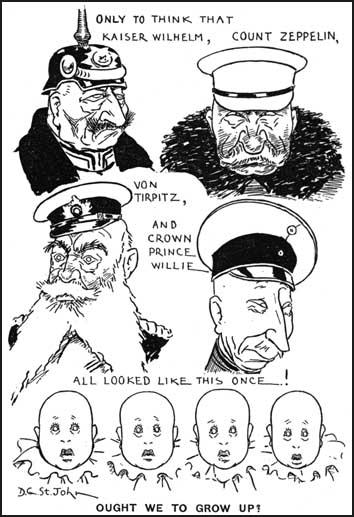

Prince Wilhelm

Prince Wilhelm, eldest son of Kaiser Wilhelm II and Augusta Victoria, was born in 1882. As a young man he associated with the group in Germany supporting militarism and imperialism.

On the outbreak of the First World War, Prince Wilhelm was given command of the German 5th Army. Victory in the Ardennes helped his military reputation and he served as a field commander on the Western Front throughout the war.

Wilhelm took part in the German offensive at Verdun in February 1916 and at the Aisne in May 1918. He resigned his commission at the Armistice and joined his father in exile in Holland. Prince Wilhelm died in 1951.

Primary Sources

(1) Prince Wilhelm, My War Experiences (1923)

When the world historical decision as to war or peace was given on August 1, with the signature of the Mobilisation Decree the whole Imperial Family was gathered together in His Majesty's ante-room. I was called in and my father, looking very grave, said to me in the presence of the Imperial Chancellor, the Chief of the General Staff, the War Minister, and the Secretary of State for the Imperial Navy: "I have appointed you Commander of the Fifth Army, You're to have Lieutenant-General Schmidt Von Knobelsdorf as Chief of Staff. Whatever he advises you must do".

With grateful hearts for the high employment provided for us by our Mobilisation Orders, we sons left the Castle, proudly conscious of our youthful vigour and cheered by an enormous crowd. But deep in my heart I was wrestling with grave thoughts about the war I had seen coming so long and so anxiously. Our political situation could not have been more unfavourable. Germany and Austria unaided against a whole world. How was it to end? But there was no time for gloom.

Everyone, whether soldier or civilian, man or woman, realised that right was on our side and wanted to share the duty and responsibility of the common defence of our sorely-menaced Fatherland. At that time the vast majority of the German people regarded the military solution of the ever-increasing political tension as the end of a nightmare. Our most unfortunate foreign policy had led to our complete isolation and produced recurring external crises which in recent years had ended more than once in a diplomatic retreat and loss of prestige for Germany. But now a storm for which Germany was in no way responsible was to clear the sultry atmosphere, and the oppressive ring of 'encirclement' was at last to be broken. After the war Germany would once more breathe freely, we hoped; she would have settled with her enemies and envious rivals, and be able to develop to a degree quite unsuspected. Those were the thoughts of the plainest man in the street in his genuine patriotic emotion.