The Autobiography of Julie Balderstone

My Paternal Grandfather

Charles (but known as Charlie) Cox was born in 1904, in West Sussex. He was born in the small village of Greatham, south of Pulborough. He was a real Sussex country boy and was a labourer all of his life. He left school at 14 and, as far as I am aware, had no ambition beyond having a good time drinking, gambling and chasing women. This accounted for the fact that my paternal grandmother divorced him before the last of his five children had finished school.

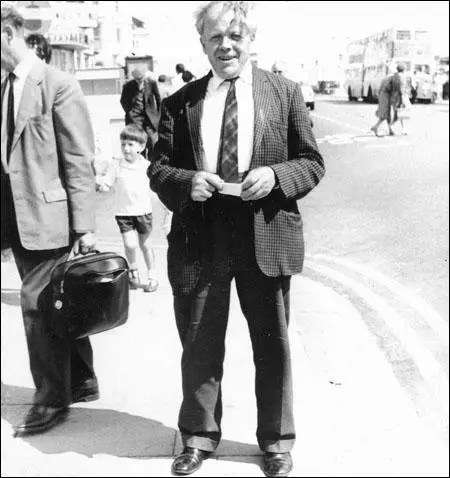

I did not know my paternal grandfather very well. I must have been aged around 16 or 17 years when I met him. He came to our home as he had nowhere to live and my parents let him have a room with us. He was not the sort of man to chat. He was retired and made himself busy in the garden in the vegetable patch for part of the time he was with us. In the evenings, he would not join the rest of the family, watching TV, but used to sit on his own in the other room and I always felt a bit sorry for him but I was probably too busy with my love-life, and also shy of him, to try to engage with him much. We lived in the little village of Watersfield and he would still go into Pulborough at the weekends to engage in his beloved betting on the horses. My memories of him are sitting with a paper folded at the racing pages and studying the form.

Although these were my first true memories of him I did have others. That is my mum had told me stories in which he played a part and so I had sort of memories of him from before then. We are told that we regularly edit memories and so the pictures I carried in my head from my mum’s stories might well be found to be stored in the place where true memories are stored or, more certainly, would make the connections in my head in the same way as true memories. One of the things that my mum told me about him was that he was absolutely positive that he remembered being born. I, and I expect you too, find this hard to believe. But we can’t ever really know someone else’s mind. We hear about fantastic things such as an autistic person being able to count all of a box of matchsticks as they fall to the floor or someone coming out of a coma and being able to speak another language or play the piano where they couldn’t before. Perhaps we should take this as a we just don’t know.

My mum told me that he had lived with them, for a while, when they were quite newly married but moved out when he got an offer of a Council place. I suppose this would have been around the early 1950s. Once out of the house, he no longer had anything to do with us. I don’t believe he ever really did anything positive for my father other than the great thing of giving him life. He was a man that thought you should know your place. My brother often recalls what he used to say to him around election times: “My boy, you should vote for them Tories. There’re the ones with the money. They know a thing or two.” He used to talk about “proper people”, or people who had “been up to Lun’on” and therefore knew a thing or two. He used to refer to some people as proper people as “they have a motor-car” and would get really angry with my mum, who was a person who didn’t judge people on what they had but who they were in their personalities, and would say “I have a motor-car.” which at that time was a real old banger. Obviously, my mum, dad me and my siblings were not proper people!

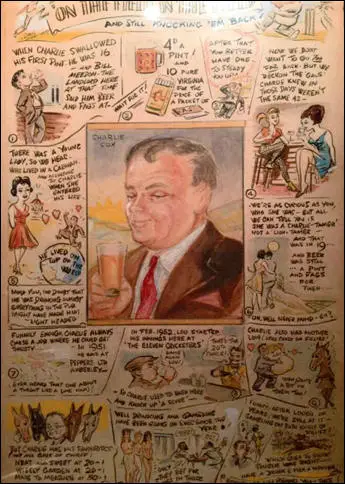

My paternal grandfather was a regular at The Eleven Cricketers, a pub in Storrington at the time; no longer a pub. They commissioned a cartoon style drawing of him telling the tale of his life (see below). This was entitled On the field, in the field. This hung on the wall of the pub for many years. It now hangs on the wall of my brother’s hallway and he hopes to pass it on in his family. My grandfather, as far as I am aware, didn’t seem to want very much from life but, reading the cartoon of his life (no. 5), perhaps he was disappointed in love. I was married when he died. He died in hospital with cancer. My mum told me that he refused treatment saying that “I’ve had a good innings.” and that he was content and ready to go.

I thank God/my lucky stars that my father was not a bit like his father. I don’t believe we should judge him though. He was a man of his time, education (or lack of) and place. He didn’t seem to want much from life and perhaps was fairly content with how it had panned out – except he would always have liked to enjoy more winnings on the horses!

My Maternal Grandfather

I never knew my maternal grandfather, John Harold Goodall, born on May 27th 1890 in Cosham, Hampshire. My memories of him come from what my mother told me about him. I know that she loved him very much and he loved her too, and she treasured that as, almost, every time she spoke of him, it was with a smile on her face. I know that he fought with the Green Howards, during the first world war, and was mentioned in dispatches. During the second world war he was a council clerk of building works and lived in Caterham, Surrey.

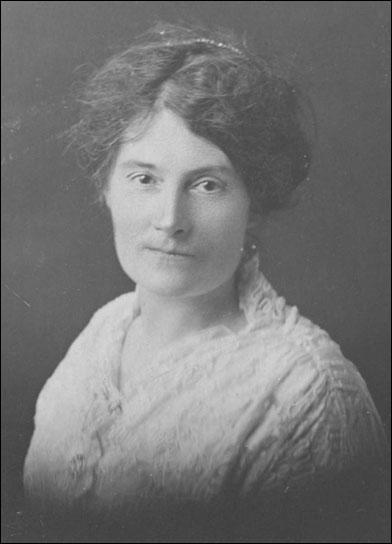

My mother often recounted the way in which her parents met. My maternal grandmother was living in the small village of Nutbourne, West Sussex. Her mother must have had a photo portrait done of her, as a young woman, and the photo was in the window of the photographer. I am not sure where the premises were, perhaps Nutbourne or Pulborough. Apparently my grandfather saw the photo and decided to seek the her out. When he first saw her out walking he asked “Where are you going sweet maid?” and apparently she replied “A milking sir.” That was the start of the romance. I don’t know how old he was when he started courting my grandmother but they married in 1915 when he was aged 25 years. They then built a family of six children (seven births; one still born) of which my mother was the youngest.

My mum said that she used to look forward to her father coming home from work and she would sit on his lap and comb his hair. He always made a fuss of her and she felt much loved by him. At this time they were living in Caterham, Surrey, and mum recalls that her parents would take her to the big departmental store in Croydon where she would look at the toys and they would have afternoon tea. He was a generous man and liked to indulge his family with what he could. During the war he was not adverse to obtaining food and drink on the black market, which it seemed was fairly easy to do, because of all of the troops stationed in and around Caterham. I think my grandfather may have been a member of the Masons, as mum used to talk about her older sisters and her mother buying lovely materials and having beautiful gowns made up for a yearly ball.

My grandfather was fortunate enough to be able to have a car and mum recalls them driving down to Bognor for holidays. I am not familiar with 1930s cars but mum used to say that she would sit on the outside of the back of the car on what she called a dickie seat, which she really enjoyed; obviously only in good weather!

My grandparents lived in a bungalow (I don’t know if they owned it or if it was rented) which was opposite a factory. Unfortunately this led to it being bombed during the war though, fortunately, not causing any fatalities in the family. Having family connections in the village of Watersfield, West Sussex, my grandfather moved them all to a rented house: Park View, Sandy Lane, Watersfield. At this time, this small village had a shop, separate post office, two pubs and a butchers. Like so many modern villages, it is now just houses.

My grandfather lived a good life and liked a good time which involved lots of outings, with his wife, out drinking. This led to him developing liver disease which he died of in 1945, aged only 55 years. My mother was 16 years old at the time of his death. My mother said she was a very innocent and naïve girl and young woman and it took her a long time to grow up. She thought this was partly because of growing up during the war years and being totally indulged and allowed to get-way with things because the adults around her didn’t know whether any of them would be alive the next day. When her father was very ill my mum told me that he used to slip in and out of comas. When he was dead he was, as was the custom of the day, laid out in his coffin in one of the rooms surrounded by strong smelling lilies. My mother said that she used to sit with him begging him to wake up before they came and buried him. It was a great shock to my mum when he died and it caused her to stop menstruating. She never liked the smell of lilies for the rest of her life.

My Paternal Grandmother

My paternal grandmother was born Ivy Streeter; 1911 to 2008. I have no happy memories associated with her except that I, and my two siblings, did always get a small gift from her at Christmas. The lack of love towards my father’s family was not because she was a hard woman incapable of being loving towards her grandchildren, but because she had no love for my father and, therefore, none for us. I was witness to her being loving towards my cousins, the children of one of her daughters and I know, although I didn’t see it, that she loved her other four children and grandchildren.

I believe that my paternal grandmother grew up in the country and her father, who worked breaking stone or similar, and helped support the family by keeping a pig, chickens and growing what food he could. He did this despite losing a leg in an early automobile accident. She had two older brothers which she didn’t meet until after the war (WW1) was over. She has recounted stories to my brother, a much more sociable character than myself and someone who has made more contact with my father’s side of the family, about growing up this way and how they would use absolutely every scrap of any animals butchered. It is clear that it was a hard up-bringing.

My nan’s life with her first husband, Charlie Cox, was hard, as he was a drinker, womaniser and gambler. She divorced him before all of her five children had left school. I know that she worked hard to bring up her family and in the appropriate months, she used to work picking fruit and potatoes. My father used to say that they were never allowed to speak at the dining table and that the butter was reserved only for the adults, the children could have margarine or jam on their bread but never both. As a young man, when he got lodgings while working in Guildford, he was still required to send home his keep for his board and room.

My father (like my mother)was disabled when born, with club feet. He was sent to hospital for a long time and, fortunately, had the condition corrected. I do not know how long he was away from home (the time of two years seems to ring a bell) but long enough that when he came back he kept calling his mum, nurse. My grandmother was always disparaging about cripples as she called them and this might have been the reason for the lack of love for my father.

I think my first memory of my grandmother was of her standing in the sitting-room doorway of our prefab bungalow. I didn’t know what was going on at the time but the long curtains that were hanging at the sitting-room windows were taken down and some shorter curtains put in their place. My mother later told me the story and I think, because it was upsetting for my mother, that I picked up on the emotion and it stays in my memory. My father spent the whole of his life trying to do well and impress and get the approval of his mother, among others. The curtains hanging at the sitting-room windows were lovely and had been given to my parents by my mother’s sister-in-law, my parents being extremely poor and not having much. My nanny, as we called my grandmother, had seen them and told my dad that she would like them and would exchange them for some others. My mum didn’t want to do this but my father had his way; this was obviously the upset I was picking up on. My mum told me this cost her the friendship of her sister-in-law.

As I mentioned, we would get a small Christmas gift from our nanny but it would be left with our parents and not given in person. I do remember getting a holiday gift from her of a stick of rock. My female cousins, who lived on the same estate as us, and who I would sometimes play with, received, what I thought were, lovely play glass Cinderella style shoes amongst other things.

I remember going around to my nan’s house (I would have been around 5 or 6 years old), which was also on the same estate, to see if my cousins were there. I stood on the path and she came out of the side door to where the rubbish bin was. She had a tray of cakes in her hand which she was going to put into the bin. I remember clearly that she looked at me and hesitated but then put the cakes into the bin anyway. I told my mum about this when I got home and I remember how upset she was; again probably why I remember. I don’t recall feelings of being hungry as a child, but I know that my mum, especially in the earlier days of their marriage, often went without and often had to struggle to get food on the table for us. I imagine that to my nan these cakes were stale but she must have known our plight and I think it was typical of her to act as she did in relation to my parents.

The only time that my nan had anything to do with us, and then not much, was when my father was doing well. I remember an incident, probably aged 7 or 8 years old, when she was standing on the pathway to our home with her husband, our step-grandfather. My dad left the home and went out to talk to her. Again, my mum recounted the story that they had come to borrow some money from my father to buy a car. They didn’t come into the house as they probably knew that my mother would not want to help. I believe my dad did help at this time, although he probably shouldn’t have done, but that was the way he was.

The only other time I remember getting a present from our nan was, again, when my father was doing well. I was aged around 9 or 10 and my sister 6 or 7 years. She came to visit us in the house we were living in at Graffham and both my sister and I had a present of a dress from her. I know that I thought it very pretty but my mum was scathing about it, saying how cheap it was. Of course by this time, there was no good feelings between my mum and my grandmother.

As an older man my father would visit his mother from time to time. I remember the story that my mother told me that they were having a discussion, I don’t know about what, but my nan swiped my dad around the head. My father was so upset about this, as you could imagine, as he was now a man of around 56/57 years and his mother still treated him as a child. Even though my mum had no love for my grandmother, she did persuade my dad to forgive his mum and eventually he went to see her again. My mum did this as she knew it was important to my dad; not for my grandmother.

My mum told me that, even at my dad’s funeral, my grandmother was going on about her poor Charlie, my dad’s much beloved brother, and had no feelings or understanding towards my mother in her extreme deep grief; not a good word about my dad.

Before my nan died, she was living on her own after the death of her third husband. I remember my mum saying that she phoned occasionally hoping that my mum would go and see her. My mum said that it was sad that my nan had been so hostile to her and my father through the years as otherwise she would have driven over and taken her out for rides to break her boredom.

I have other memories which involve my paternal grandmother but I think they are more the story of my parents, but they show how she was towards them. I have to say that if you asked an account of my grandmother from my cousins, they would tell a story of love. Perspective is everything.

Julie Caroline Balderstone: My Maternal Grandmother

My maternal grandmother, who we called nanny, was born Cicel Gladys Craven in 1888 and lived for 92 years, dying in 1980, the year my son was born.

I don’t know a lot about her earlier life but know that she lived in the village of Nutbourne when younger. I believe that she had been brought up to be as much of a lady as was possible in their circumstances, of which I am not really very knowledgeable. I know that throughout her life, until her old bones made it impossible, she carried herself with her head high and her back straight. I have a memory about having a holly leaf put down the back of her clothing to make her sit up straight! Being taught to walk with her head held high might also have come about as it seems that her father deserted a wife and two children living in Lyminster, Littlehampton and made a life with her mother, who was 18 years his junior, in Nutbourne. She was the first of four children in her father’s second union. My brother, who has done some of our family history, believes that her father lived using a slightly altered name. It seems that he may have just disappeared from his first family’s lives and started a new life just about 28 miles away. I suppose this was easier to do all of those years ago when people tended to live their lives where their home was. We don’t believe her parents actually got married but my nan’s surname was changed from Craven to Duke, her father’s surname.

I remember my nan talking about their family having a pony and trap. She was quite a snobbish woman, even when reduced to low circumstances later in her life, and considered herself and her family a cut above many others. I think she had a very comfortable upbringing. Possibly because of the way of her parents union, she had no time for the church so I suppose her family may have lived slightly outside of polite society.

My grandmother married at the age of 27, and had six children (and one stillbirth) and lived a comfortable life until the death of her husband in 1945 from liver disease, when she was aged 57 years old. While married, she was able to afford the good things in life and had holidays and lovely clothes. After the death of her husband, she took in washing to make ends meet. She was a dutiful and hardworking mother, although she did not love my mother, possibly because she was born with the disability of clubfeet. Another reason, for the lack of love for my mother, may have been that she was the youngest of six children and my grandmother did not want another child. My mother told me the story that her mum had had to have a baby punched from her during childbirth; I assume this was the still-birth. I was also told that she often fell off of her bike while pregnant. I wonder if she was trying to lose the baby. I also wonder if, for some children born with club feet, the reason might be that the expectant mothers try old wives remedies for aborting the baby in the first three months of gestation, with this deformity being the result. These are just my own thoughts and I have no way of knowing how things really were. My grandmother always knew immediately on drinking her first cup of tea of the morning that she was pregnant; by the odd taste I assume. Apparently she used to say “Jack. You’ve done it again!”

My mother told me that she remembered her parents asking her if she would mind going to hospital to have an operation and that she would be away for a long time. My mum remembered saying that she didn’t mind and that she would write letters although, at the age she was, she was unable to write. She remembered going with her parents to see what must have been a consultant. She said they were in a line with other family groups and that the consultant came along and went down the line, quite quickly, and said to her and her parents that he would “cut here” on mum’s legs and moved on to the next family. My mother was never sent for the operation. This obviously had a huge impact on her life. My mum always thought, and it was just a thought and feeling, that the reason she wasn’t sent for the operation was because her mum was affronted by the fact that they were treated in this group setting and not individually; it was not good enough for her.

My mum always said how hard working her mum was even when her dad was alive. She had six children and so was always busy just getting things done and never had time to actually talk to my mum. Her house and washing was always spick and span with good food on the table for everyone. Although my mum didn’t feel loved by my grandmother she, mostly, did her duty by her. There are three incidents, relating to my mum, that she recounted to me about her mother which I couldn’t put down on paper and shows her at her worst. But we can never truly know what prompts people to do what they do. She did, as many of that age did, use the belt on her children. I think, perhaps, she might have found six children too much after a carefree and, perhaps, spoilt childhood.

After the war and living as a widow she still had a houseful to contend with. Four of her children were living with their wives and husbands, and some babies, with her. Again, I think the pressure of this prompted her to act in ways that most people would find unacceptable and which my father did. This meant that my parents, my mother expecting her first child, my brother, moved out into rented accommodation well beyond their means.

I think my first memory of my nan was when I was sitting on the toilet and my mum and nan crept up and poked their heads around the corner and looked at me. My mum told me that I was still very little, perhaps two years old, and that I had opened the door from the sitting-room to the hallway and made my way to the toilet, climbed up and perched on the seat and, for the first time, used the toilet. My mum said that, on noticing I had moved into the hall, she was about to call out to me but my nan shooshed her and said to wait to see what I would do. She obviously thought it prudent to get the children to be independent as soon as possible!

My main memory of my nan was of her visiting us each Wednesday and always bringing a sweet of some sort, such as a wagon-wheel. We always gave her a kiss on the cheek but that was as close as we got. She always used to insist on her and my mum having an afternoon nap, which my mum never wanted, and I remember my mum defending me when my nan complained that I was being too noisy. My father used to walk her down to the bus-stop after dinner for her to catch the bus home. She always brought my mum something to help out such as a packet of tea and biscuits.

I wouldn’t say that I had love for my nan; or at least not love as I experience it with other members of my family. I certainly had feelings for her. She had always been there in my life. When I was about 16 years old I decided to treat her to afternoon tea out with my boyfriend as I felt sorry for her not going out much. I had never been for afternoon tea myself but it seemed that it was right for my nan and I could afford it from my waitress earnings. We went to a tearoom in Pulborough and when we had been served, she began to cry. I was unable to ask her why but just tried to comfort her a bit and we got through it. I never attempted anything like it again. I wonder if it brought back too many happy memories of which were long past. Or perhaps, she was just so touched by my treat.

My nan lived with my uncle for many years at the end of her life. She would still enjoy going out for a drink with the family and found it hard when she got older and my uncle didn’t take her with him. This resulted, once, in them coming back from the pub to find her laying out in the snow, wanting to die. This was at a time when my parents didn’t have a car and my mum was unable to get to see her and take her out for rides which she always did, on the regulation Wednesday, when she had wheels at her disposal. Obviously this was a very low point of her life.

When my son was born, I remember taking him to see her and her holding him in her arms and her being pleased with the visit. This was not long before her death so she would have been 91 years old. When she went into hospital, at the end of her life, l remember my mum saying that perhaps I should visit her. I was busy with my son and said I would go but not immediately. Of course it was too late and she died before I did visit. I think, for me at least, I was at an age when I didn’t really realise that people that you cared about would disappear from your life. I knew about death but didn’t understand it.

My mother: Dulcie Millicent Cox (nee Goodall)

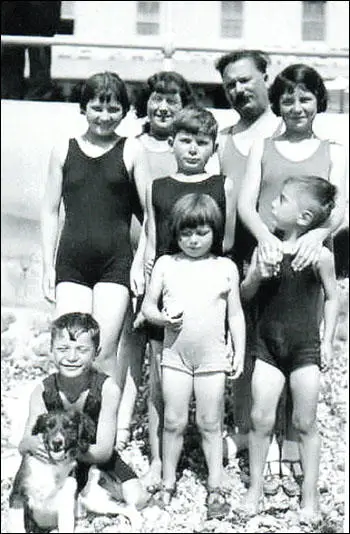

My mum, born 21st November 1928, was the youngest of six children (Carol, Norman, Ivy, Cecil, Clifford, Dulcie). She was born in Kenley, Surrey but the family moved to Caterham in Surrey while she was still a toddler.

is centre in the front with her favourite brother Cliff (Clifford) with the family dog

and her brother Cecil beside her. Her older brother Norman is behind her

with her sister Ivy left of Norman and her favourite sister Carol, right of Norman.

Her parents are at the back.

My mother was born with club feet and this had a great impact on her life but she did not let herself be defined by this. She was a brave, even fearless woman and, perhaps like so many children, I did not fully appreciate all that she was until much later in my own life.

My mother told me that her first memory was of her sitting in her highchair banging the tray with a wooden spoon. She had many happy memories of her childhood and felt spoilt by her father who she felt truly loved her. She used to wait for him to come home from work and she would sit on his lap and comb his hair. She didn't have a great relationship with her mother and felt that her mother didn't really love her although she was dutiful towards her.

walking to one side of the pram and her aunty Ivy, her mum’s sister, is walking next to her mother.

A story recounted to me was of her visit with her mother to a hospital in which she and her mum were sat in a long line of other mums with their child with the same type of disability as mum. Then, who she thought must have been a medical consultant, came along and looked at each child saying they would “Cut here.” and then he quickly moved on to the next mum and child. Mum was very young when this happened but it was a clear memory. She said that her father asked her later if she would mind going to the hospital and that they wouldn’t be able to visit her often and it would be for a very long time. She replied that she didn’t mind, realising even at that young age that she might be made to be like other children, and that she would write to them although she couldn’t write at this time. She didn’t go to hospital for that operation and long stay which meant that she stayed disabled for the rest of her life. However, she did go to hospital later as a young child to have an operation but it didn’t solve her problems long-term, although it might have made some difference at that time. She was very unhappy and said the nurses were not nice to her. Because of that she decided to run away. She went off on her own but when finding herself at the top of a very long flight of hard steps, which she thought she would not be able to manage to go down safely on her own, she went back. She hadn’t been missed.

Children can be cruel and mum suffered much bullying when a child. A favourite story of hers was when she started school and had to put up with much from many of the other children. She decided to do something about this. After school, she hurried home and filled her pockets with stones on the way. Once home, she climbed up onto the roof of the bungalow where she lived and waited for the children who had bullied her to walk past. Stones were thrown at the bullies and eventually they tracked down where she was. Faces were turned up to her in astonishment. She then said “I bet none of you can climb up here!” There was only one girl, Hazel, who dared to climb up and join my mum; they then became the greatest of friends. She told me that she never had any more trouble with those particular bullies.

Unfortunately mum still continued to suffer from bullying. She recounted the story of getting her own back on a girl who had consistently made fun of her. She managed to get her to a place where she was able to lean back against a fence for support, grab the girl’s hair, pull her head down and thump her on her back. Mum was always a child to get her own back.

She told the story of another girl who had made great fun of her feet and legs and the way she walked consistently, over a long period of time. One day this girl needed a play-mate and asked to play with mum. Mum went along with this but then got her at the end of an alleyway and produced a knife and, having cornered the girl, started stabbing at her feet making her jump out of the way. My mother’s older brother Cliff, who always came to her rescue, on this occasion, rescued the other girl.

who was her protector when they were young.

These stories might make you think that my mother was a terrible person; she wasn’t. In fact she was someone who had been shaped, like most of us, by her personality and her experiences. It is easy to make a judgement about how she dealt with her tormentors but none of us were in her place.

My mum had a great protector in her one year older brother Cliff (Clifford). He came to her rescue many a time when hearing her scream when out playing and being on the receiving end of something unpleasant. I think children were much rougher in those days, or certainly going by my own experience, and the adults just seemed to let them get on with it. The adults seemed to have the attitude of children needing to sort it out for themselves and that bullying was just a part of life. Mum dealt with her bullies herself and gained respect from them for it.

Her love of her protective brother, Cliff, was probably why I only heard this story once or twice and it took my brother to remind me of it. He had heard it lots of times from our uncle. Again, this incident happened when mum was quite young and was using a pair of scissors to cut something. Her brother Cliff was with her and screwed up the skin on one of his knees and was foolish enough to say to mum “I bet you won’t cut this!” Of course mum did and it was bad enough that it left quite a scar which my uncle often showed and declared as a war wound. You will realise by now that my mother was always having to prove herself to her peers and was not the type of child to refuse a dare.

brother and protector, when young, Cliff (Clifford).

I saw my mum as having a good instinct with people. She seemed to be able to know who were nice people and who weren't and it was never anything to do with what they wore or their class. She told me that her favourite older sister snobbishly said to her, when she was a child that, she did like to play with the rough, common children. Perhaps when you are disabled you see people's minute reaction to you that other people might not notice and that gives you an insight into their character.

Mum said that she had happy memories of regularly being taken to the department store by her parents and looking at the toys and having afternoon tea. They also used to go on holiday to Bognor, with mum sitting in the Dickie seat of their car for the journey. She remembered watching the Punch and Judy shows and eating ice-creams. She counted herself lucky despite the fact that her mum would use the strap on her, and her siblings, if they misbehaved. The discipline of the children fell to my grandmother. My mum, in later life, felt that this was unfair towards her mum; her dad always being the one to spoil the children.

Mum often talked about the difference between her mother and her friend, Hazel's mother. My grandmother was hard-working and kept a spick and span house but never had time for my mum. Her friend's mother was what we would call slovenly but always had time to chat. If the girls had any problems it was to Hazel's mum that they turned to for advice. Mum said that the house was not the cleanest. During the summer months she said the kitchen would be full of flies and they would hold their breath and race through the kitchen. Mum remembered Hazel's mum with much fondness though, and she was dearly loved by all of her children. This stark difference between the two mothers guided mum to choose a middle path to both of them in relation to housework and child-care.

My mum didn't have many happy memories of school. She particularly hated geography as the teacher used to come round and thump her on her back. She said that in the end she didn't go to school on the afternoons when the geography lessons were due. The only lesson she liked was English which was taught by a very kind Indian teacher whom she said liked her and was kind to her - the implication being that all the other teachers were unkind. It shows the difference a kind teacher can make as mum was always good at spelling and had beautiful hand-writing. Later on, her father did pay for her to go to train as a shorthand typist but her heart wasn't in it. I think that the idea of sitting all day at a typewriter would have .felt like a prison sentence to her.

Mum remembered, very clearly, a day that for some reason she hadn't gone to school. It was 4 th November 1940 and she would have been 12 years old. A lone enemy bomber, without any air-raid warning, dropped several bombs on Caterham, damaging shops and houses, and opening fire on children leaving the school; mum's school. She says that she ran out of the house on hearing the noise, looking up to the sky. She saw the plane flying low down and she and the pilot clearly looked into each other's faces. He decided not to shoot at her. She was lucky.

Mum had many memories of the war. One was of going down into the Anderson shelter that her dad had dug into the garden. She said it was cold and damp but she didn't have much to say about it as she usually focussed on the happier memories. Having said that, the family had a dog; a German Shepherd bitch called Lady, which she and her friend Hazel often took out for walks. Lady had to wear a muzzle during the war. Mum did tell me the story about a man regularly exposing himself to the two girls and trying to lure them into the bushes. Eventually they decided to face him while taking the muzzle off of the dog and the dog growled at the man, straining at the leash. Lady was a good guard dog, protective of mum as he had known her from birth but she said he was as soft and gentle with her as a dog could possibly be. This dealt with the problem man and he never tried to lure them into the bushes again. Mum had a life-long love of dogs.

Mum would have been 11 years old when the war started. She would have been coming into puberty and she told me the story of when she first started menstruating. Even although she had two older sisters she had no idea what was happening when she started bleeding. She says that she went into tell her mum feeling very frightened. Her mum just threw her a belt and sanitary pad and told her to go and put it on. She had no idea what to do. She also told of the story of falling over and of a boy seeing her knickers which she had been told leads to having a baby. She ran home to her mum worried about what had happened. These incidents had the effect on her to make sure that her children were never that ignorant about anything to do with their bodies.

Mum always laughed and said that she and her friend Hazel were silly, innocent, naïve young girls. Although she was disabled and walked ‘funny' (her legs didn't develop properly below the knee and her feet turned inwards and she walked up high on her toes) she was a fairly confident young girl, not one to be put down by people. I don't know at what point, but mum started going by the name of Peggy as she was a big fan of the singer known professionally as Peggy Lee.

As mum progressed through her young teenage years she said she would often spend hours in her room listening to music, especially playing the record over and over of Blueberry Hill by Fats Domino . She was also mad about The Ink Spots . She told me that she had a large poster on her bedroom wall of Stalin, as she thought him a very handsome man. At that time she didn't understand his politics but in later life she had a hatred of him.

Mum clearly remembered the start of the Blitz. As the aeroplanes flew overhead, she with other children, she would have been almost 12 years old, ran out to look up at them, excited and not realising the danger. Of course the adults called them back inside.

She said that she and Hazel spent a lot of time walking in the park which led onto the golf-links where the French-Canadian soldiers would hang out. There were a lot of soldiers and not enough girls of their age, so even although mum and Hazel were young the soldiers chatted and flirted with them and they happily flirted back. She said that they would be playing one minute and then retreating behind a bush to put too much lipstick on, Vaseline on their eyelashes and rake a comb through their hair, and then go parading about. She said that the soldiers were always gentlemen and they were never hurt or upset in any way. The soldiers would call them over saying "Peggy, come and talk to us." and they would be given chocolate, gum and cigarettes. Like lots of children from this time, mum was smoking at a very young age being highly influenced by the film stars and thinking it was sophisticated. She had many happy memories from this time although as an older woman, she reflected on how the soldiers were bored and probably very frightened of what was to come.

Mum had two older sisters. One was named Ivy and she was a real flirt. Mum remembered that one day a soldier was waiting outside for Ivy for an arranged date. When Ivy left the house she said that she wasn't Ivy buts her twin sister and that Ivy would be out in a minute and left the poor man waiting while she sauntered off to meet another soldier. The girls had the pick of the men at this time.

Her other sister who, was 8 years older than mum and was her favourite and quite beautiful, fell in love with a French-Canadian soldier and became pregnant. Mum's father threw her out of the house and she went to live with their aunt Emmy and uncle Cress, her mother's brother. She was only allowed back into the house once my grandmother talked my grandfather round. Although mum loved her dad dearly, she always said the he was a man who saw women as either to go on a pedestal or as sluts, and she never agreed with that way of thinking. Her sister's boyfriend admitted to being the father of the child. I have a faint memory that he might have been married. My aunt carried on seeing the man she loved and, unfortunately for her, became pregnant again. Her boyfriend this time denied that he was the father of this child as he was going to get into trouble with his superiors. We are sure the child was his. My mum talked about happy times looking after these two boys, taking them out in the pram. She was very close to them when they were small and I remember them visiting mum later when they were grown young men.

Her other sister who, was 8 years older than mum and was her favourite and quite beautiful, fell in love with a French-Canadian soldier and became pregnant. Mum's father threw her out of the house and she went to live with their aunt Emmy and uncle Cress, her mother's brother. She was only allowed back into the house once my grandmother talked my grandfather round. Although mum loved her dad dearly, she always said the he was a man who saw women as either to go on a pedestal or as sluts, and she never agreed with that way of thinking. Her sister's boyfriend admitted to being the father of the child. I have a faint memory that he might have been married. My aunt carried on seeing the man she loved and, unfortunately for her, became pregnant again. Her boyfriend this time denied that he was the father of this child as he was going to get into trouble with his superiors. We are sure the child was his. My mum talked about happy times looking after these two boys, taking them out in the pram. She was very close to them when they were small and I remember them visiting mum later when they were grown young men.

Emmy (Emily) who took in her sister, Carol, when she was thrown out by her father.

During the war Mum said that her parents didn't really punish them, probably thinking they all might be dead soon, and they often pleaded that they hadn't realised the time when staying out. The UK was practicing double summer-time which meant that it stayed light really late. She said they often knew they were late but pushed the boundaries. Her brother, Cliff, would often come and find her to tell her to "Get home quick!" as they were all looking for her and her parents were cross.

Over time, and I suppose as they grew older, mum and Hazel paired up with two particular soldiers who were probably around four or five years older than them which is quite a lot when you are a young teenager. Mum's ideal man's look, at that time, was black hair and the soldier that became her boyfriend was called Blackie because of his lovely jet black hair. They would kiss and cuddle but he was always restrained and respectful with her. She says that he was in love with her and she thought herself in love with him, but it didn't compare with how she later felt about my father. Even so she had loved him and when he eventually was sent away into the battle of D-Day never to return, it broke her heart. She would have been no older than 14 years at this time. She learned about his death because he had a love letter from her in his pocket and his superiors were kind enough to let her know. He had been in the medical corps but had decided he couldn't face battle without a rifle and so transferred to the infantry and mum often wondered if things would have been different if he had not done this. After his death, his family contacted mum and wanted to meet her because Blackie had told them so much about her but she never did get to meet them.

Because of mum's disability, mum liked to wear wide trousers which she felt covered up the way she walked. She was lucky in that her parents could afford to have them made for her. She remembered going to the store to choose some material for two pairs of trousers and being shown the fabrics for clothes which she thought plain and boring. She picked out two lots of bright material, which was supposed to be for curtains, and had the trousers made up in that instead. She said that she was walking down a shopping street in Croydon, wearing one of these pairs of trousers, when a man lounging outside of a boutique saw her. He rushed inside his shop and called another man out and they watched her swish down the street. The next week a copy of the bright trousers were in the window for sale; street fashion in action.

Mum and Hazel used to spend the weekends together, staying overnight alternating between their homes. For some reason, that mum couldn't remember, they had been due to stay at mum's place but stayed at Hazel's instead. This surely saved both of their lives. It was 13 th June 1944; mum was 15 years old. This was the day that the first doodlebugs were dropped in the UK and one of them landed on the bungalow where mum lived, obliterating the bedroom where the girls would have been sleeping. A neighbour rushed and told mum what had happened and the girls rushed to mum's home where they were confronted with the bombed bungalow, confused and dazed family, and looters going through their possessions. My aunty Ivy had been bending down to pick up her son and flying glass became embedded into her bottom from the explosion. My mum's mother and sister, Carol, had to be taken to hospital. My aunt was more badly hurt and remained in hospital for some time and, fortunately, only ended up losing the hearing in one ear. The shock mum suffered caused her to stop menstruating for quite some time. She said that afterwards, every time you heard the doodle-bugs you were filled with fear but it worse when the noise stopped and you wondered where they were going to fall.

My grandmother's mother and sister were living in the little village of Watersfield, near Pulborough in West Sussex. My grandfather, I think rented, the property of Park Hill, Sandy Lane in Watersfield which was a detached four bedroomed house opposite a small terraced cottage where my great-grandmother lived and beside a field in which my great aunt Dulcie lived in a caravan with her husband. So they all moved to the country.

My mother went into a deep depression when they moved. She missed her friend Hazel and felt as if she was buried alive. She had been used to going to Croydon and loved the shops and busyness of the place. She felt the country had nothing to offer and that all of the people were ignorant. She didn't bother with herself, not washing her hair or caring about her clothing. Fortunately this came to an end when my grandmother arranged for Hazel to come down for the summer holidays.

With her friend by her side she perked up and they set about exploring the surroundings. They were soon to come across one of the characters of the village, who was known as Ma Clarke, leaning on the gate of her field. She was dressed in her customary red; each new red outfit would be worn over the last one. I imagine this behaviour developed as she aged, along with her beard. She looked at the girls approaching and told them to "Get back to the town where you belong." Of course, they just laughed at the old woman.

They saw a sign for Bignor Park and decided to walk there expecting to find a park similar to the one in Caterham. They were dumbfounded when they realised it was just the countryside! As the summer holiday progressed, mum made friends and learned that, in fact, people in the country knew a great deal more than urban people. She also learned to love the countryside and, later in life when returning from outings and passing the sign of ‘West Sussex' she always smiled and said she was home.

The village of Watersfield at this time had a shop, a Post Office, two pubs and a butcher. Unfortunately it is all just houses now. The village butted on to the village of Coldwaltham which had a village hall where a community minded lady used to arrange get-togethers for the young people on a Saturday night, a bit like a youth club really, where records would be played for them to dance to. Mum made many friends but she never talked about a really special friend like Hazel.

Park Hill, the house where they lived in Sandy Lane, was directly opposite a row of small terraced cottages where my maternal great-grandmother lived. She was bed-ridden having fallen back off of a chair while hanging some curtains and becoming paralysed because of the damage that she did to her back. Mum said she loved to go and visit her grand-mother who she said always had a lovely smile and a bit of a far-off look in her eyes which mum said made her think that she had many happy memories. She had very long hair and used to comb it with cold black tea to try to keep some colour in it.

Mum would have been 16 years old when her father, who she adored, died. He died of sclerosis of the liver, being a man who liked to have a good time, which involved drinking. He was ill for a long time, lying in bed and often going in and out of a coma. When he was laid out in a coffin at home, surrounded by lilies to keep the smell of the decaying body at bay, mum used to sit with him stroking his hand and forehead telling him to hurry up and wake up before they buried him. Once again, when he was buried, the shock of her loss resulted in her menstruation stopping for a time. Mum told me that as an adult, she was sure that the doctor had helped her father on his way. She said that the doctor used to visit regularly and give him injections to help him cope with the pain. She thought her father told the doctor that it had become too much and he wanted to go and, thankfully, he was released from his suffering. Throughout her life, she hated the smell of lilies.

Sometime after her father died mum recounted the story of her three brothers sitting around a table talking about what was to become of Dulcie. They didn’t know that she was listening but the plan was that they would each contribute a little towards an allowance for her and it was obvious that she would remain unmarried and, of course, she would stay and look after their widowed mother. This would have been like a red-rag to a bull to mum. She would prove them wrong. She had every intention of marrying and having children. She had never been short of boyfriends and she was not going to give up her life for her mother.

Mum was never a big fan of work; she was a hedonist by nature. She did have a few jobs before she married my father and became a full-time housewife and mother. She worked as a cleaner to a lovely woman in the village. Mum said that she wasn’t really any good at this job but that the woman really liked her. Her employer would go off to play tennis and mum would make a bit of an effort to clean and then perhaps help herself to a piece of cake. This led to her employer teaching her the correct way to cut a cake. Once when something had gone a bit wrong with the pressure cooker with its contents ending up on the ceiling she was asked to clean it. Mum said that she couldn’t possibly climb up on a ladder to do that and so the poor gardener was brought in to do it. At Christmas time, her employer commented that it was strange that she was not receiving her usual number of Christmas cards. It transpired that they were coming in the post and sliding across the floor and going under a large wooden chest. Mum had not moved it to sweep underneath. She told the woman that it was too heavy for her but, she admitted in the telling of her story, was probably not true. She decided to leave this work but her employer did come to see my grandmother and asked her to see if Dulcie would come back, and offered her a rise. She was well liked if not efficient!

She had at least three other jobs up until she married my father at the age of 21 years. She got a job in a factory in the village of Pulborough, a couple of miles from Watersfield. She had to catch the bus into work which arrived later than the starting time. It was a source of annoyance to the other women working in the factory when mum sauntered in late smiling, and probably winking, at the manager who also really liked her.

I think her longest job was working at The Lodge Hill Residential Centre in the village of Watersfield where she lived. This had been a country house turned into a country hotel until the outbreak of the second world-war when it was requisition by WSCC and became the headquarters of the mobile ARP Reserve until 1945. In 1946 the house and land were bought by the WSCC to provide a venue for educational opportunities, especially for young people, thus fulfilling the Council’s obligations under the 1945 Education Act. Mum worked in the kitchen and I think she enjoyed her work here. She told of the time when a film was being made of Lodge Hill and she was complimented on being the person to act in the most natural way while they were filming. I suspect that because she was used to being stared at because of her disability, she had learnt how to put people around her out of her mind when necessary.

The other job she had, which might have been where she was working when she met my father, was looking after the young children of a doctor and his wife who lived in Pulborough. She loved this job and really enjoyed taking care of her two young charges.

Boyfriends were coming onto the scene a bit more now and there were German prisoners of war in the area. Despite being bombed out by the Germans, mum never judged the prisoners she met. She didn’t really take notice of the politics of war, being more interested in having fun. Later in life, when she learned what the Nazis had done, she hated all Germans going with the idea that the only good German was a dead German; she was a woman of extremes. She went out with a German prisoner-of-war and once he showed her a photo of himself in uniform which he quickly put away when someone else came into the room. She later wondered what the uniform might have told her about this man if she had known what to look for. She remembered that he said to her that Germany wanted England to come into the war on their side and that they could have ruled the world together. Mum’s reply was “Why do you want to rule the world?” This summed her up. She was a free spirit and wanted everyone to be free.

Mum wasn’t short of friends or boyfriends and they used to catch a bus to Petworth to attend dances held there. Sometimes they had to walk back home, which would have been around 6 miles and, despite her disability, mum managed this although I am sure it was harder for her than the others. She was a strong woman. She told the story of attending a dance at Pulborough village hall. There were a lot of Polish soldiers there and one pulled her up for a fast dance. She protested but he said “Just follow me.” She managed to make it through the dance but was relieved when he let her go and pulled up another young woman to dance. They danced the jitter-bug and were so good that everyone cleared the dancefloor to watch them.

When she was 19 years old, mum had a friend by the name of Joyce Cox. Joyce had a brother called Jim or Jimmy and he owned a couple of rowing boats. Joyce lived in the village of Pulborough and it was arranged that mum would catch the bus over and Joyce and her brother would meet her at The Swan corner and her brother would take them on the river in one of his boats. Mum stepped off the bus to meet Joyce and her brother, a handsome, fair and blue-eyed young man. Mum and Jim got along well and they arranged for a repeat, without Joyce, the next day. It was in the boat later that day that Jim said to Dulcie that he was going to marry her. “Oh, are you now?” was her reply. The challenge had been set.

Mum wasn’t short of friends or boyfriends and they used to catch a bus to Petworth to attend dances held there. Sometimes they had to walk back home, which would have been around 6 miles and, despite her disability, mum managed this although I am sure it was harder for her than the others. She was a strong woman. She told the story of attending a dance at Pulborough village hall. There were a lot of Polish soldiers there and one pulled her up for a fast dance. She protested but he said “Just follow me.” She managed to make it through the dance but was relieved when he let her go and pulled up another young woman to dance. They danced the jitter-bug and were so good that everyone cleared the dancefloor to watch them.

When she was 19 years old, mum had a friend by the name of Joyce Cox. Joyce had a brother called Jim or Jimmy and he owned a couple of rowing boats. Joyce lived in the village of Pulborough and it was arranged that mum would catch the bus over and Joyce and her brother would meet her at The Swan corner and her brother would take them on the river in one of his boats. Mum stepped off the bus to meet Joyce and her brother, a handsome, fair and blue-eyed young man. Mum and Jim got along well and they arranged for a repeat, without Joyce, the next day. It was in the boat later that day that Jim said to Dulcie that he was going to marry her. “Oh, are you now?” was her reply. The challenge had been set.