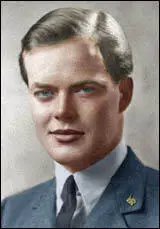

Richard Hillary

Richard Hillary, the son of a government official, was born in Sydney, Australia, on 20th April, 1919. As a child he was sent to England where he was educated at Shrewsbury School and Trinity College, Oxford. A keen sportsman he was secretary of the University Boat Club and president of the Rugby Club.

In 1938 Hillary joined the University Air Squadron and was called-up to the Royal Air Force in October 1939. The following year he became a member of 603 Squadron based at Hornchurch. He later recalled being told he was to fly a Supermarine Spitfire: "It was what I had most wanted through all the long dreary months of training. If I could fly a Spitfire, it would be worth it. Well, I was about to achieve my ambition and felt nothing I was numb, neither exhilarated nor scared "

Hillary fought during the Battle of Britain and was brought down on 29th August, 1940. Uninjured, he immediately returned to duty and over the next six days was credited with shooting down five enemy planes. In The Last Enemy he explained what it was like to kill for the first time: "He came right through my sights and I saw the tracer from all eight guns thud home. For a second he seemed to hang motionless; then a jet of red flame shot upward and he spun to the ground... For the next few minutes I was too busy looking after myself to think of anything, but when, after a short while. they turned and made off over the Channel, and we were ordered to our base, my mind began to work again. It had happened. My first emotion was one of satisfaction, satisfaction at a job adequately done, at the final logical conclusion of months of specialised training. And then I had a feeling of the essential rightness of it all. He was dead and I was alive; it could so easily have been the other way round; and that would somehow have been right too. I realised in that moment just how lucky a fighter pilot is. He has none of the personalised emotions of the soldier, handed a rifle and bayonet and told to charge. He does not even have to share the dangerous emotions of the bomber pilot who night after night must experience that childhood longing for smashing things. The fighter pilot's emotions are those of the duellist-cool, precise, impersonal. He is privileged to kill well. For if one must either kill or be killed, as now one must, it should, I feel, be done with dignity."

When on patrol over the Kent coast on 3rd September, 1940, Hillary was involved in combat with a BF109. "Then, just below me and to my left, I saw what I had been praying for - a Messerschmitt climbing and away from the sun. I closed in to 200 yards, and from slightly to one side gave him a two-second burst: fabric ripped off the wing and black smoke poured from the engine, but he did not go down. Like a fool, I did not break away, but put in another three-second burst. Red flames shot upwards and he spiralled out of sight. At that moment, I felt a terrific explosion which knocked the control stick from my hand, and the whole machine quivered like a stricken animal. In a second, the cockpit was a mass of flames: instinctively, I reached up to open the hood. It would not move. I tore off my straps and managed to force it back; but this took time, and when I dropped back into the seat and reached for the stick in an effort to turn the plane on its back, the heat was so intense that I could feel myself going." Hillary managed to bale out of his burning Supermarine Spitfire and landed in the Channel.

Rescued by the Margate Lifeboat, the badly burnt Hillary was sent to the Queen Victoria Burns Unit in East Grinstead, where he was treated by the plastic surgeon, Archibald McIndoe. "Gradually I realized what had happened. My face and hands had been scrubbed and then sprayed with tannic acid. My arms were propped up in front of me, the fingers extended like witches' claws, and my body was hung loosely on straps just clear of the bed... The time when the dressings were taken down I looked exactly like an orang-utan. McIndoe had pitched out two semi-circular ledges of skin under my eyes to allow for contraction of the new lids. What was not absorbed was to be sliced off when I came in for my next operation, a new upper lip."

A fellow patient, Geoffrey Page, later recalled: "Richard Hillary paused at the end of the bed and stood silently watching me. He was one of the queerest apparitions I had ever seen. The tall figure was clad in a long, loose-fitting dressing gown that trailed to the floor. The head was thrown right back so that the owner appeared to be looking along the line of his nose. Where normally two eyes would be, were two large bloody red circles of raw skin. Horizontal slits in each showed that behind still lay the eyes. A pair of hands wrapped in large lint covers lay folded across his chest. Cigarette smoke curled up from the long holder clenched between the ghoul's teeth."

After leaving hospital he went to the United States where he gave lectures for the Ministry of Information on the Second World War. While on the tour he wrote his book, The Last Enemy, that dealt with his experiences during the Battle of Britain.

Richard Hillary returned to the Royal Air Force and was killed along with his navigator when he crashed his Blenhiem on 8th January, 1943.

Primary Sources

(1) Richard Hillary wrote about flying a Supermarine Spitfire for the first time in his autobiography The Last Enemy (1942)

The Spitfires stood in two lines outside 'A' Flight pilots' room. The dull grey-brown of the camouflage could not conceal the clear-cut beauty, the wicked simplicity of their lines. I hooked up my parachute and climbed awkwardly into the low cockpit. I noticed how small was my field of vision. Kilmartin swung himself on to a wing and started to run through the instruments I was conscious of his voice, but heard nothing of what he said. I was to fly a Spitfire. It was what I had most wanted through all the long dreary months of training. If I could fly a Spitfire, it would be worth it. Well, I was about to achieve my ambition and felt nothing I was numb, neither exhilarated nor scared I noticed the white enamel undercarriage handle "Like a lavatory plug," I thought.

Kilmartin had said "See if you can make her talk." That meant the whole bag of tricks, and I wanted ample room for mistakes and possible blacking-out. With one or two very sharp movements on the stick I blacked myself out for a few seconds, but the machine was sweeter to handle than any other that I had flown. I put it through every manoeuvre that I knew of and it responded beautifully. I ended with two flick rolls and turned back for home. I was filled with a sudden exhilarating confidence. I could fly a Spitfire; in any position I was its master. It remained to be seen whether I could fight in one.

(2) Richard Hillary wrote about shooting down his first German aircraft in his book The Last Enemy (1942)

We ran them at 18,000 feet, twenty yellow-nosed Messerschmitt 109s, about five hundred feet above us. Our Squadron strength was eight, and as they came down on us we went into line astern and turned head on to them. Brian Carberry, who was leading the Section, dropped the nose of his machine, and I could almost feel the leading Nazi pilot push forward on his stick to bring his guns to bear. At the same moment Brian hauled hard back on his control stick and led us over them in a steep climbing turn to the left. In two vital seconds they lost their advantage.

I saw Brian let go a burst of fire at the leading plane, saw the pilot put his machine into a half roll, and knew that he was mine. Automatically, I kicked the rudder to the left to get him at right angles, turned the gun button to 'Fire', and let go in a four-second burst with full deflection. He came right through my sights and I saw the tracer from all eight guns thud home. For a second he seemed to hang motionless; then a jet of red flame shot upward and he spun to the ground.

For the next few minutes I was too busy looking after myself to think of anything, but when, after a short while. they turned and made off over the Channel, and we were ordered to our base, my mind began to work again. It had happened.

My first emotion was one of satisfaction, satisfaction at a job adequately done, at the final logical conclusion of months of specialised training. And then I had a feeling of the essential rightness of it all. He was dead and I was alive; it could so easily have been the other way round; and that would somehow have been right too. I realised in that moment just how lucky a fighter pilot is. He has none of the personalised emotions of the soldier, handed a rifle and bayonet and told to charge. He does not even have to share the dangerous emotions of the bomber pilot who night after night must experience that childhood longing for smashing things. The fighter pilot's emotions are those of the duellist-cool, precise, impersonal. He is privileged to kill well. For if one must either kill or be killed, as now one must, it should, I feel, be done with dignity. Death should be given the setting it deserves; it should never be a pettiness; and for the fighter pilot it never can be.

(3) Richard Hillary, flew with 603 Squadron during the Second World War. He was shot down on 3rd September, 1940.

I was peering anxiously ahead, for the controller had given us warning of at least fifty enemy fighters approaching very high. When we did first sight them, nobody shouted, as I think we all saw them at the same moment. They must have been 500 to 1000 feet above us and coming straight on like a swarm of locusts. The next moment we were in among them and it was each man for himself. As soon as they saw us they spread out and dived, and the next ten minutes was a blur of twisting machines and tracer bullets. One Messerschmitt went down in a sheet of flame on my right, and a Spitfire hurtled past in a half-roll; I was leaving and turning in a desperate attempt to gain height, with the machine practically hanging on the airscrew.

Then, just below me and to my left, I saw what I had been praying for - a Messerschmitt climbing and away from the sun. I closed in to 200 yards, and from slightly to one side gave him a two-second burst: fabric ripped off the wing and black smoke poured from the engine, but he did not go down. Like a fool, I did not break away, but put in another three-second burst. Red flames shot upwards and he spiralled out of sight. At that moment, I felt a terrific explosion which knocked the control stick from my hand, and the whole machine quivered like a stricken animal. In a second, the cockpit was a mass of flames: instinctively, I reached up to open the hood. It would not move. I tore off my straps and managed to force it back; but this took time, and when I dropped back into the seat and reached for the stick in an effort to turn the plane on its back, the heat was so intense that I could feel myself going. I remember a second of sharp agony, remember thinking "So this is it!" and putting both hands to my eyes. Then I passed out.

(4) Richard Hillary was saved by the Margate Lifeboat when he was shot down on 3rd September, 1940. He was immediately taken to the Queen's Victoria Burns Unit in East Grinstead.

Gradually I realized what had happened. My face and hands had been scrubbed and then sprayed with tannic acid. My arms were propped up in front of me, the fingers extended like witches' claws, and my body was hung loosely on straps just clear of the bed.

Shortly after my arrival in East Grinstead, the Air Force plastic surgeon, A.H. McIndoe, had come to see me. Of medium height, he was thick set and the line of his jaw was square. Behind his horn-rimmed spectacles a pair of tired, friendly eyes regarded me speculatively.

"Well," he said, "you certainly made a thorough job of it, didn't you?" He stated to undo the dressings on my hands and I noticed his fingers - blunt, captive, incisive. By now all the tannic had been removed from my face and hands. He took a scalpel and tapped lightly on something white showing through the red granulating knuckle of my right fore-finger. "Four new eyelids, I'm afraid, but you are not ready for them yet. I want all this skin to soften up a lot first."

The time when the dressings were taken down I looked exactly like an orang-utan. McIndoe had pitched out two semi-circular ledges of skin under my eyes to allow for contraction of the new lids. What was not absorbed was to be sliced off when I came in for my next operation, a new upper lip.

(5) Geoffrey Page was shot down and badly burnt on 30th September, 1940. He met Richard Hillary while being treated at the Queen's Victoria Burns Unit in East Grinstead.

Richard Hillary paused at the end of the bed and stood silently watching me. He was one of the queerest apparitions I had ever seen. The tall figure was clad in a long, loose-fitting dressing gown that trailed to the floor. The head was thrown right back so that the owner appeared to be looking along the line of his nose. Where normally two eyes would be, were two large bloody red circles of raw skin. Horizontal slits in each showed that behind still lay the eyes. A pair of hands wrapped in large lint covers lay folded across his chest. Cigarette smoke curled up from the long holder clenched between the ghoul's teeth. There was a voice behind the mask. It was condescending in tone. "Bloody fool should have worn gloves." Hillary's hands were equally badly burned and for the same reason - no gloves.