Maud Joachim

Maud Joachim, the daughter of Henry Joachim and Ellen Margaret Smart, was born in Paddington, London, on 1st August 1869. Her father was born in of Hungary had become a "Naturalized British Subject" in 1856. He was a wool merchant who employed four clerks in 1871. (1)

Henry Joachim was the father of five children: Gertrude Ellen (born 1865), Harold Henry (born 1868), Maud Amalia Fanny (born 1869), Dorothy Margaret (born 1874) and Nina Mary Joachim (born 1876). At the time of the 1881 Census, 56-year-old Henry Joachim was a "Retired (Wool) Merchant". (2)

Maud was the niece of Joseph Joachim, the violinist and composer and close friend of Ursula Bright. (3) Joachim studied Moral Science at Girton College (1890-1893). At the time of the 1891 Census, 21-year-old Maud Joachim was living with her parents and three sisters - Gertrude, 25, Dorothy, 16, and Nina, 14, at No.13 Airlie Gardens, Kensington, London. At the time they employed four servants. (4)

Women's Social & Political Union

Maud Joachim joined the Women Social & Political Union (WSPU) in 1907. (5) According to the Votes for Women newspaper she became "one of the most strenuous and devoted workers in the cause." Committed to militant action she was arrested on 11th February 1908, after taking part in a demonstration on the House of Commons and was sentenced to six weeks' imprisonment. (6)

On the 30th June, 1908, she was selected to be a member of a deputation led by Emmeline Pankhurst from Caxton Hall, taking a resolution to the House of Commons demanding an immediate effective measure to give votes to women. During the procession several women were arrested. This included Maud Joachim, Mary Postlethwaite, Florence Haig, Marion Wallace-Dunlop, Mary Phillips, Jessie Kenney, Elsie Howey, Edith New, Mary Leigh, and Vera Wentworth. (7) Haig pointed out that newspapers described women's deputations as "raids". (8)

When she was arrested Maud Joachim he said: "I am so happy." (9) On 1st July, 1908, the women appeared in court. Mr Muskett, who appeared for the Metropolitan Police, said that there was really nothing new to be said in regard to these cases."Many ladies in the Union came there with the intention of being arrested." (10) Florence Haig said: "Mr. Asquith has shown us that peaceful demonstrations are useless." (11)

After being released from prison Maud Joachim wrote an account of being in prison. "At last we are taken into a room, where we are ordered to undress and to give up all our property, which is inventoried. Then we are weighed, and told to have a bath, the last bath we shall see for a week, and then we put on the strange and unsightly prison garments, which are covered with broad arrows, and are doled out to everybody without any regard to size or fit.... Then at last one is taken up to one’s own cell, and thenceforward one loses one’s name, and is called only by the number of the cell; the door is slammed and locked, and one looks round one’s domain, so tired that it is a relief to be alone at last, and to be able to go to bed. It is a relief, too, to find that the cell is clean, and in winter is well lighted by electric light, which is turned out soon after eight o’clock. The bedstead consists of three planks, fastened to cross-pieces, so as to stand about four inches from the ground, and is about 27 inches wide. The mattress is a model of what a mattress should not be, as besides, being very hard, it is full of lumps, which always catch one in sensitive spots. There is also a little hard stool, and a table fixed from an angle of the wall near the door; and in the door there is a spy-hole, through which the wardresses can look in."

Life was made as difficult as possible for suffragette prisoners. "Except for that daily half-hour’s chapel and the daily hour of exercise in a gravelled yard, we stay all day long in our cells during the first month, we have a certain amount of needle-work to do, and are allowed two books a week from the prison library, such as it is... The wardresses and prison officials go a good long way towards doing so, especially when, as is often the case, they speak to one in a quite gratuitously rude and insulting tone of voice. I know that so many people find it gets on their nerves to hear the door of their cell locked on them, but for my own part, I so much dislike the contact with the prison officials that I am almost glad to have the door between me and them." (12)

Winston Churchill

As a senior member of the Liberal Party government Winston Churchill became a target for the Women's Social & Political Union. Churchill had been a long-term opponent of votes for women. As a young man he argued: "I shall unswervingly oppose this ridiculous movement (to give women the vote)... Once you give votes to the vast numbers of women who form the majority of the community, all power passes to their hands." His wife, Clementine Churchill, was a supporter of votes for women and after marriage he did become more sympathetic but was not convinced that women needed the vote. When a reference was made at a dinner party to the action of certain suffragettes in chaining themselves to railings and swearing to stay there until they got the vote, Churchill's reply was: "I might as well chain myself to St Thomas's Hospital and say I would not move till I had had a baby." However, it was the policy of the Liberal Party to give women the vote and so he could not express these opinions in public. (13)

In public he supported the principle of women's suffrage as it was party policy. In private he was totally opposed as he thought it would be to the disadvantage of the Liberal Party. Should women be given the vote on the same limited basis as men (which would favour the Conservative Party) or should there be a massive extension of the franchise to enable all adults to vote (which would favour the Labour Party). Churchill warned the Cabinet that if the government introduced plans for women's suffrage he would probably have to resign. (14)

In February 1909, Joachim worked alongside Ada Flatman in Aberdeen. Along with Catherine Corbett, Adela Pankhurst and Helen Archdale they decided to disrupt Churchill's public meeting at Kinnaird Hall in Dundee. Pankhurst and two men, Owen Clark and William Carr, hid themselves in an attic and threw stones, bricks and slates at the roof-light of the hall, calling out "votes for women". Meanwhile, Corbett, Joachim and Archdale, led a group of supporters that charged the barricades thrown up around the hall. (15)

The Dundee Courier reported: "Their sudden appearance (Catherine Corbett, Maud Joachim and Helen Archdale) had a magical effect on the mob. Surging round the women, they threw themselves against the solid wall of police. The officers fought valiantly, but were utterly helpless to stem the great human tide… Meanwhile the crowd time and again charged the police, and succeeded in reaching the barricades… The crowd in Reform Street were now incensed to fever pitch, and several ugly rushes were made to force a way to Bank Street." (16)

The women were arrested but Corbett later paid tribute to the courage of the Dundonians who had rioted for three hours: "they would not stop until they got the barricades down, they were glorious." (17) Each woman made a lengthy speech in court and was sentenced to ten days in prison. They all went on hunger-strike. Churchill disagreed and told the local newspaper that the women were "a band of silly, neurotic women". (18) The Bystander reported that after her release from prison Joachim paraded the West End on horseback to advertise the “cause” of women's suffrage. (19)

Blathwayt Family

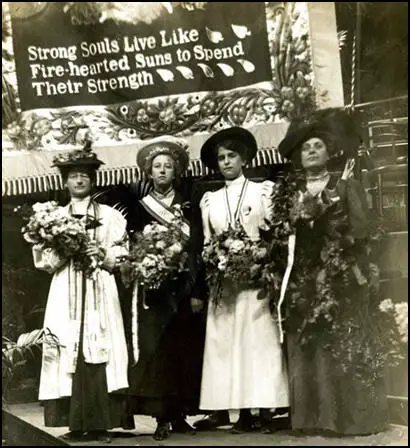

In 1882 Colonel Linley Blathwayt purchased Eagle House near Batheaston, a large house set in four acres of land. Blathwayt was a supporter of the Liberal Party. His wife, Emily Blathwayt, and his daughter, Mary Blathwayt, also held progressive political views and were both advocates of women's suffrage. In July 1906 both Emily and Mary joined the Women Social & Political Union (WSPU) and began sending donations to its treasurer, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence. (20)

Colonel Blathwayt was sympathetic to women's suffrage Colonel Blathwayt photographed the WSPU visitors. These were then signed and sold at WSPU bazaars. Members of the WSPU who endured hunger strikes went to stay with the family. Colonel Blathwayt also designed an arboretum which was planted with trees by suffragette ex-prisoners. Eventually, fifty-four trees with their accompanying place were established there. (21)

Mary Blathwayt recorded in her diary that Annie Kenney had intimate relationships with at least ten members of the WSPU at Batheaston. Blathwayt records in her diary that she slept with Annie in July 1908. Soon afterwards she illustrated jealousy with the comments that "Miss Browne is sleeping in Annie's room now." The diary suggests that Annie was sexually involved with both Christabel Pankhurst and Clara Codd. Blathwayt wrote in her diary that "Miss Codd has come to stay, she is sleeping with Annie." (22) Codd's autobiography, So Rich a Life (1951) confirms this account. (23)

The historian, Martin Pugh, points out that "Mary writes matter-of-fact lines such as, Annie slept with someone else again last night, or There was someone else in Annie's bed this morning. But it is all done with no moral opprobrium for the act itself. In the diary Kenney appears frequently and with different women. Almost day by day Mary says she is sleeping with someone else." (24)

Colonel Blathwayt decided to create a suffragette arboretum in a field adjacent to the house. The idea was for women to be invited to plant a tree to commemorate their prison sentences and hunger strikes. On 23rd April 1909 Emily Blathwayt recorded in her diary that Annie Kenney, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Constance Lytton and Clara Codd all planted trees. "Beautiful day for the tree planting and Linley photographed the three in a group at each tree. Annie put the West one, Mrs. P. Lawrence, South, and Lady Constance the East. Miss Codd came to the field." (25)

Maud Joachim was a regular visitor to Eagle House and on 17th June 1910 Colonel Linley Blathwayt planted a tree, a Thujopsis Dolabrata, in her honour in his suffragette arboretum in a field adjacent to the house. (26)

Black Friday

In January 1910, H. H. Asquith called a general election in order to obtain a new mandate. However, the Liberals lost votes and was forced to rely on the support of the 42 Labour Party MPs to govern. Henry Brailsford, a member of the Men's League For Women's Suffrage wrote to Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the National Union of Woman's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), suggesting that he should attempt to establish a Conciliation Committee for Women's Suffrage. "My idea is that it should undertake the necessary diplomatic work of promoting an early settlement". (27)

Emmeline Pankhurst, the leader of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) agreed to the idea and they declared a truce in which all militant activities would cease until the fate of the Conciliation Bill was clear. A Conciliation Committee, composed of 36 MPs (25 Liberals, 17 Conservatives, 6 Labour and 6 Irish Nationalists) all in favour of some sort of women's enfranchisement, was formed and drafted a Bill which would have enfranchised only a million women but which would, they hoped, gain the support of all but the most dedicated anti-suffragists. (28) Fawcett wrote that "personally many suffragists would prefer a less restricted measure, but the immense importance and gain to our movement is getting the most effective of all the existing franchises thrown upon to woman cannot be exaggerated." (29)

The Conciliation Bill was designed to conciliate the suffragist movement by giving a limited number of women the vote, according to their property holdings and marital status. After a two-day debate in July 1910, the Conciliation Bill was carried by 109 votes and it was agreed to send it away to be amended by a House of Commons committee. However, when Keir Hardie, the leader of the Labour Party, requested two hours to discuss the Conciliation Bill, H. H. Asquith made it clear that he intended to shelve it. (30)

Emmeline Pankhurst was furious at what she saw as Asquith's betrayal and on 18th November, 1910, arranged to lead 300 women from a pre-arranged meeting at the Caxton Hall to the House of Commons. Pankhurst and a small group of WSPU members, including Dorinda Neligan, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Sophia Duleep Singh and Anne Cobden Sanderson were allowed into the building but Asquith refused to see them. Women, in "detachments of twelve" marched forward but were attacked by the police. (31)

Votes for Women reported that 159 women and three men were arrested during this demonstration. (32) This included Maud Joachim, Ada Wright, Catherine Marshall, Eveline Haverfield, Anne Cobden Sanderson, Mary Leigh, Vera Holme, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Kitty Marion, Gladys Evans, Cecilia Wolseley Haig, Maud Arncliffe Sennett, Clara Giveen, Eileen Casey, Patricia Woodcock, Vera Wentworth, Winifred Mayo, Mary Clarke, Florence Canning, Henria Williams, Lilian Dove-Wilcox, Minnie Turner, Bertha Brewster, Charlotte Haig, Lucy Burns and Grace Roe. (33) Joachim was released without charge. (34)

Window Smashing Campaign

On 1st March, 1912, Emmeline Pankhurst, Mabel Tuke and Christabel Marshall, each armed with stones, got out of their taxicab in Downing Street, and broke two windows of Number 10. All three women were arrested immediately. During the next hour, at fifteen-minute intervals, 150 suffragettes, broke the windows of shops and businesses in the Haymarket, Piccadilly, Regent Street, the Strand, Oxford Street and Bond Street. "The WSPU justified the upping of the militant tempo by arguing that women and retail shops and offices had interests in common, and as such these businesses should support women's suffrage and put pressure on the government to give women the vote." (35)

Maud Joachim was one of those arrested during this window-smashing campaign. According to Votes for Women: "From in front, behind, from every side it came - a hammering, crashing, splintering sound unheard in the annals of shopping... At the windows excited crowds collected, shouting, gesticulating. At the centre of each crowd stood a woman, pale, calm and silent." (36)

Christabel Pankhurst justified this new strategy by arguing that so far WSPU militant action "had not sufficiently embarrassed them... the Government and the public are far too calm in the face of these things. The sufferings of the militant women have not been felt keenly enough. That is why commercial and private property is attacked." (37)

Maud Joachim had been sentenced to six months' imprisonment during the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) window smashing campaign. In April 1912 she appealed against the conviction because the court had insisted she had been guilty of conspiracy. Joachim claimed that she had no knowledge that it had been organised by the WSPU. The appeal was dismissed. (38)

Maud Joachim was transferred to Maidstone Prison because, the Home Office reported, "she is a person of some influence with the others and is fomenting trouble at Holloway." She continued this work at Maidstone where, towards the end of June, the suffragette prisoners joined in the hunger strike for political status that had been started at Holloway. Joachim was forcibly fed for two days and then released. (39)

Maud Joachim claimed that there were benefits of going to prison with fellow suffragettes: "What one finds on joining the WSPU is, that one is brought into contact with a great number of people whose ideals are the same as one's own, and that the isolation and the reproach are things of the past." (40)

After her release from prison Maud Joachim continued to campaign for the civil rights of suffragettes. She wrote from her own on Erskine Hill, Hampstead, to The Globe: "In reference to the treatment of the suffragist “conspirators” (so-called) now in prison, I should like to call attention to your readers to the fact that by sending them each to a separate prison, the Home Secretary is adding to the mental torture of absolutely solitary confinement to their punishment, for suffragist prisoners are not allowed to associate with other prisoners, even if they should consider such association fitting." (41)

Arson Campaign

Some members of the WSPU, including Adela Pankhurst became concerned about the increase in the violence as a strategy. She later told fellow member, Helen Fraser: "I knew all too well that after 1910 we were rapidly losing ground. I even tried to tell Christabel this was the case, but unfortunately she took it amiss." After arguing with Emmeline Pankhurst about this issue she left the WSPU in October 1911. Sylvia Pankhurst was also critical of this new militancy. (42)

Emmeline Pankhurst gave permission for her daughter, Christabel Pankhurst, to launch a secret arson campaign. She knew that she was likely to be arrested and so she decided to move to Paris. Attempts were made by suffragettes to burn down the houses of two members of the government who opposed women having the vote. These attempts failed but soon afterwards, a house being built for David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was badly damaged by suffragettes. (43)

At a meeting in France, Christabel Pankhurst told Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence about the proposed arson campaign. When they objected, Christabel arranged for them to be expelled from the the organisation. Emmeline later recalled in her autobiography, My Part in a Changing World (1938): "My husband and I were not prepared to accept this decision as final. We felt that Christabel, who had lived for so many years with us in closest intimacy, could not be party to it. But when we met again to go further into the question… Christabel made it quite clear that she had no further use for us." (44)

Others like Maud Joachim, Elizabeth Robins, Jane Brailsford, Laura Ainsworth, Eveline Haverfield and Louisa Garrett Anderson showed their disapproval by ceasing to be active in the WSPU and Hertha Ayrton, Lilias Ashworth Hallett, Janie Allan and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson stopped providing much needed funds for the organization. Sylvia Pankhurst was also very critical of the arson campaign. She was also unhappy that the WSPU had abandoned its earlier commitment to socialism and disagreed with Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst's attempts to gain middle class support by arguing in favour of a limited franchise. Sylvia now concentrated her efforts on helping the Labour Party build up its support in London. (45)

East London Federation of Suffragettes

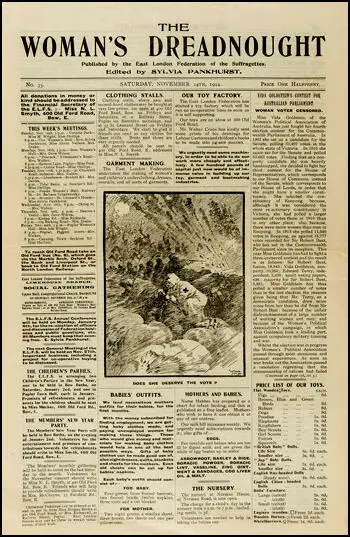

In 1913, Sylvia Pankhurst, with the help of Maud Joachim, Keir Hardie, Norah Smyth, Julia Scurr, Mary Phillips, Millie Lansbury, Eveline Haverfield, Lilian Dove-Wilcox, Florence Haig, Nellie Cressall and George Lansbury established the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELF). An organisation that combined socialism with a demand for women's suffrage it worked closely with the Independent Labour Party. (46)

As June Hannam has pointed out: "The ELF was successful in gaining support from working women and also from dock workers. The ELF organized suffrage demonstrations and its members carried out acts of militancy. Between February 1913 and August 1914 Sylvia was arrested eight times. After the passing of the Prisoners' Temporary Discharge for Ill Health Act of 1913 (known as the Cat and Mouse Act) she was frequently released for short periods to recuperate from hunger striking and was carried on a stretcher by supporters in the East End so that she could attend meetings and processions. When the police came to re-arrest her this usually led to fights with members of the community which encouraged Sylvia to organize a people's army to defend suffragettes and dock workers. She also drew on East End traditions by calling for rent strikes to support the demand for the vote." (47)

Norah Smyth, supplied most of the money for this venture. Appointed treasurer of the EFL she helped finance their weekly newspaper, The Women's Dreadnought that first appeared in March 1914. Although they printed 20,000 copies, by the third issue total sales were only listed as just over 100 copies. During processions and demonstrations, the newspaper was freely distributed as propaganda for the EFF and the wider movement for women's suffrage. (48)

Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst objected to the formation of the East London Federation of Suffragettes and by the end of 1913 Sylvia was on the verge of being expelled from the Women's Social & Political Union. Christabel, who was living in exile, demanded she came to see her in Paris. "So insistent were the messages… I agreed to go… I was smuggled into a car and driven to Harwich. I insisted that Norah Smyth, who had become financial secretary of the Federation, should go with me to represent our members… Like me, she desired to avoid a breach. Dogged in her fidelities, and by temperament unable to express herself under emotion, she was silent… She (Christabel) urged, a working women's movement was of no value; working women were the weakest portion of the sex: how could it be otherwise? Their lives were too hard, their education too meagre to equip them for the contest." Christabel added: "You have your own ideas. We do not want that; we want all our women to take their instructions and walk in step like an army!". (49)

Christabel also complained about ELF's close links with the Labour Party and the trade union movement. She especially objected to her attending meetings addressed by George Lansbury and James Larkin and her friendship with Keir Hardie and Henry Harben. In view of all this, Christabel concluded, Sylvia's East London suffragettes had to become an entirely separate organization, having proven their inability to operate in compliance with WSPU policy. (50) Emmeline Pankhurst wrote to Sylvia: "You are unreasonable, always have been, and I fear always will be." On 29th January 1914, Christabel expelled Sylvia from the WSPU. (51)

Maud Joachim also left the WSPU. According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928 (2000): "In August, when war was declared, she (Maud Joachim) was with Sylvia Pankhurst in Dublin. They returned to London immediately and Maud Joachim became secretary of an unemployment bureau set up by the East London Federation of Suffragettes, appealing for work for the local unemployed, and was also manager of the ELFS toy factory until edged out by a more dominant personality." (52)

In 1933, 64-year-old Maud Joachim travelled to San Francisco, California, with Miss Edith Storrs. At the time of the 1939 National Register (29th September), Maud Joachim was residing at 17, Somerset Terrace, St Pancras, London, and was living on "Private Means". (53)

Maud Joachim, who lived at Mouse Cottage, Steyning, died aged 77, on 16th February 1947 leaving effects valued at £9,311.

Primary Sources

(1) Maud Joachim, Votes for Women (7th May 1908)

Looking at the special reports of the Women’s Congress in Rome, which have reached me, I am struck by the prominent part which the women of the aristocracy are taking in the women’s movement. A good many members of the Chamber of Deputies were present in the Congress, watching its proceeding with a view.

The Congress attacked with the most praiseworthy courage and energy every phase of the problems which modern life presents, and made it very obvious that women’s duties are co-extensive with the whole length and breadth of the social fabric. A great part of the energies of the women has hitherto been directed to public education on important social problems; in fact, they seem to have realised almost more vividly than we have done over here the necessity of supplementing legislation by instructing as well an awakening public conscience as to the duties of citizenship, and especially as to sexual morality and hygiene.

(2) The Sheffield Daily Telegraph (2nd July 1908)

In the case of Maud Joachim who had a previous conviction, a penalty of finding two sureties, with the three months was imposed. When arrested she said: "I am so happy."

(3) Votes for Women (9th July 1908)

As a consequence of the proceedings on Tuesday, June 30, described in our last issue, twenty-seven of the defendants appeared before Mr Francis at the Westminister Police Court, all charged with obstructing the police in the execution of their duty. Those found guilty included Maud Joachim, Mary Clarke, Jessie Kenney, Marion Wallace Dunlop, Mary Phillips, Elsie Howey, Florence Haig, Vera Wentworth, Mary Leigh and Edith New.

(4) Maud Joachim, Votes for Women (1st October 1908)

From the moment when one goes into court and hears the topsy-turvey evidence of the police and sees the queer faces of the magistrate and his colleagues gazing at one, to the moment when one leaves Holloway after having served one’s time there, one seems to be living in a fantastic dream, only one knows that one could never dream anything so nonsensical. The policeman who arrests one, the official who takes down one’s name and address, and records the charge against one, all treat one with the greatest respect; yet the offence with which one is charged is – practically – that of disorderly conduct, and the sentence that is passed on a woman who had really been disorderly, and violent, and drunken, and abusive.

I will not describe our experiences in Court, but after we came out we are shut behind iron bars into a corridor, from which a series of dark and dirty police-cells, until the police vans are ready to take us to Holloway. Meanwhile, those of our friends who are able to get permission come and talk to us through the bars, round which we crowd, feeling very much like wild beasts; and we try to remember the messages that we want to send to friends and relations, knowing that this is the last chance we shall have for a long time, for one visit and one letter are allowed after four weeks, and no sooner.

Then at last we are let out one by one, in the order of our arrest, locked into the tiny cells of Black Maria, and jolted away to Holloway, a long and dismal ride. There our names, addresses, age, and occupations are written down once more, we are asked whether we can read and write, and are locked, usually by threes into dark little cells, where we wait again, interminably, and are interviewed by matron or principal wardress before being taken to be examined by the prison doctor. Later an extremely nasty cocoa and meat and a loaf of brown bread are thrust in upon us, and we do what we can with them.

At last we are taken into a room, where we are ordered to undress and to give up all our property, which is inventoried. Then we are weighed, and told to have a bath, the last bath we shall see for a week, and then we put on the strange and unsightly prison garments, which are covered with broad arrows, and are doled out to everybody without any regard to size or fit. There is a certain difficulty in deciding which is bathmat and which is underclothing, but the thing is really simple; there is no bath-mat at all, and everything one sees one is expected to put on. However, I was never obliged to wear more than I wanted to.

Then at last one is taken up to one’s own cell, and thenceforward one loses one’s name, and is called only by the number of the cell; the door is slammed and locked, and one looks round one’s domain, so tired that it is a relief to be alone at last, and to be able to go to bed. It is a relief, too, to find that the cell is clean, and in winter is well lighted by electric light, which is turned out soon after eight o’clock. The bedstead consists of three planks, fastened to cross-pieces, so as to stand about four inches from the ground, and is about 27 inches wide. The mattress is a model of what a mattress should not be, as besides, being very hard, it is full of lumps, which always catch one in sensitive spots. There is also a little hard stool, and a table fixed from an angle of the wall near the door; and in the door there is a spy-hole, through which the wardresses can look in…

Except for that daily half-hour’s chapel and the daily hour of exercise in a gravelled yard, we stay all day long in our cells during the first month, we have a certain amount of needle-work to do, and are allowed two books a week from the prison library, such as it is.

“Stone walls do not a prison make,” but the wardresses and prison officials go a good long way towards doing so, especially when, as is often the case, they speak to one in a quite gratuitously rude and insulting tone of voice. I know that so many people find it gets on their nerves to hear the door of their cell locked on them, but for my own part, I so much dislike the contact with the prison officials that I am almost glad to have the door between me and them.

(5) The Daily Mirror (30th June 1909)

Thousands of people gathered in Parliament Square and thronged the approaches to the Houses of Parliament long before the expected suffragette deputation to the House of Commons left Caxton Hall last night.

In anticipation of a general disturbance nearly 3,000 police had been drafted from all parts of London with Rochester Row and Cannon Row stations as early as five o'clock in the afternoon.

The meeting at Caxton Hall which prefaced the raid began at 7.30. The hall was packed with suffragettes, wearing scarves and ribbons and sashes of purple, white, and green, the colours of the Women's Social and Political Union.

Mrs Pethick Lawrence was in the chair and Mrs Pankhurst and the other members of the chosen deputation – limited to eight women – supported her on the platform. The deputation that ultimately set out consisted of: Mrs Pankhurst, Mrs Mansell, Mrs Saul Soloman, Miss Catherine Margenson, Mrs Haverfield, Dorinda Neligan, Miss Maude Joachim and Mrs Frank Corbett.

Of the above Mrs Pankhurst is of course, one of the original leaders of the militant suffragettes. Mrs Mansell, the wife of Colonel Mansell, is a granddaughter of the late Lord Wimborne and the first cousin of Mr. Ivor Guest, M. P. one of the founders of the Anti-Suffrage League.

Mrs Saul Solomon is the widow of a former Premier of Cape Colony, Miss Margesson is a daughter of Lady Isabel Margeson, Miss Joachim, a niece of the famous violinist, and the Hon Mrs Haverfield, a daughter of the third Lord Abinger.

Mrs Corbett is a sister-in-law of Mr C. H. Corbett, M.P., Miss Neligan is seventy-nine years of age…

Inspector Scantlebury handed her (Mrs Pankhurst) a message from the Premier's private secretary, stating that it was not possible for Mr Asquith to see them, as he had already expressed the opinion upon the subject.

"We can't accept that!" exclaimed Mrs Pankhurst, and immediately afterwards endeavoured to push the two inspectors away. "If we can't get anything else we must assert our rights."

A long conversation ensued, and then a scrimmage, during which Inspector Jarvis was rather roughly handled. Mrs Pankhurst it is alleged, striking him violently on the face with her hand.

Immediately the police closed round the women, who were taken into custody, struggling violently.

(6) Votes for Women (2nd July 1909)

Miss Maud Joachim, a niece of the famous violinist, since joining the movement in February, 1908, has been one of the most strenuous and devoted workers in the cause. She was arrested on February 11, and on June 30, 1908, and has already served four and a half months’ imprisonment. She has taken part in many bye-elections and in the special London campaign just completed.

(7) The Dundee Courier (18th October 1909)

Their sudden appearance (Catherine Corbett, Maud Joachim and Helen Archdale) had a magical effect on the mob. Surging round the women, they threw themselves against the solid wall of police. The officers fought valiantly, but were utterly helpless to stem the great human tide… Meanwhile the crowd time and again charged the police, and succeeded in reaching the barricades… The crowd in Reform Street were now incensed to fever pitch, and several ugly rushes were made to force a way to Bank Street.

(8) Northern Daily Telegraph (20th October, 1909)

The five suffragettes, including Miss Adela Pankhurst and Miss Maud Joachim, who were apprehended last night in connection with the disturbance at Mr Churchill’s meeting at Dundee, were each fined today.

(9) Votes for Women (29th October 1909)

From the accounts which follow it will be seen that more and more is the sympathy of the British public on the side of the women in their protests against Cabinets Ministers. At Dundee especially the splendid section of the crowds, among home, says one of the women, there was hardly an enemy, would have led to serious rioting but for the action of the police is taking the women under their charge…

An account of the great Dundee protest last week shows that Miss Joachim, Mrs Archdale, and Mrs Corbett were arrested, not for any act on their part, but because the police found the crowd so intensely sympathetic to the Suffragettes that they feared a riot. This is corroborated by the local papers…

Mrs Corbett, Miss Joachim, and Mrs Archdale led the "rushes" waving the colours and shouting "Votes for Women! Down with the barricades! Rush the barricades! Follow me, man!" They all came, and there was a furious melee of crowd, police, and mounted police.

(10) Votes for Women (26th April 1912)

Two cases in which suffragist prisoners appealed against their sentences on points of law were heard before Justices Lawrence, Pickford and Avory on Monday last (22 April). Miss Maud Joachim, sentenced to six months imprisonment, appealed against the conviction. Mr Blanco White said that his client was charged along with a Miss Fargus with breaking windows in Regent Street. There was no evidence of conspiracy, and his client denied all knowledge of Miss Fargus’s intentions.

Mr Justice Lawrence, in delivering judgment, said counsel’s contention was that Miss Joachim was not liable, because she did not know that Miss Fargus had broken immediately before a larger window. If, in point of fact, they were acting in concert by the direction or suggestion of a person whose orders they took in the matter they were equally guilty of the offence, although they had no knowledge of one another and had no direct communication with each other. The appeal was accordingly dismissed.

(11) Maud Joachim, letter to The Globe (24th June 1913)

In reference to the treatment of the suffragist “conspirators” (so-called) now in prison, I should like to call attention to your readers to the fact that by sending them each to a separate prison, the Home Secretary is adding to the mental torture of absolutely solitary confinement to their punishment, for suffragist prisoners are not allowed to associate with other prisoners, even if they should consider such association fitting. (Maud Joachim, Erskine Hill, Hampstead, N. W.)

(12) Votes for Women (1st August 1913)

The suffragettes of Bow, the Men’s Federation for Women’s Suffrage, and the East London Federation of WSPU are to be congratulated on the magnificent mass meeting of protest which they organised in Trafalgar Square on Sunday afternoon (27th July 1913). A huge and conspicuously working-class crowd gathered early to welcome the long procession as it marched into the Square with colours flying, singing the Marseillaise, and it was evident that throughout the afternoon the men and women who made spirited denunciatory speeches from each side of the column had the entire sympathy of their audience…

Eleven men and thirteen women arrested after the Trafalgar Square meeting on Sunday were brought before Sir John Dickinson at Bow Street on Monday and Wednesday. Maud Joachim fined 40s.

(13) George J Barnsby, The Struggle for the Vote in the Black Country 1900-1918 (1994)

Suffragette propaganda continued in Wolverhampton after the election, led by Emma Sproson. The election appears to mark a watershed in the attitude of both men and women to female suffrage and Emma seems never to have the experience she had in April 1907 when the Express & Star reported a meeting on the Market Place under the heading 'Suffragettes Mobbed.' Emma was greeted with "Whoa Emma; Have a drop of gin; go and look after the kids; what ay yer paid for doing this?" and much more. The main speaker was Mrs. Baines from Stockport and she got no better treatment. 'The crowd was inclined to be spiteful rather than good humoured', the paper reported in a prize understatement. Stones were thrown and a Mr. Duffy of the Wolverhampton Highways Department was injured.

Emma was also showing the resourcefulness which was always a feature of whatever she did. In November 1907 she made a scene at the police court. A woman was being tried for being drunk. Emma said that women had no part in making laws and therefore should not be vied under them; she was removed from the Court.

At the end of April Gladice Keevil was announcing her plans for May. She was bringing Mrs. Pethwick-Lawrence into Wolverhampton on Wednesday the 3rd to a meeting at Victoria Hall and the next day there was a meeting in the Market Square. There was also to be an open-air meeting the following Saturday in the Market place. Gladice was in Wolverhampton the whole of that week holding Market place meetings on Saturday, Monday, Thursday and Friday with a meeting at Wednesfield on the Tuesday and Tettenhall the next day.

In June 1908 the WSPU held a great Hyde Park rally when the purple, white and green first became their official colours. A vain was booked to leave Wolverhampton at 7.15 am, return fare 7/6d. When activity resumed in the autumn, the Women's Freedom League brought Mrs. Despard to Wolverhampton for a meeting at the Central Hall, where, according to the Wolverhampton Journal she "showed a tolerance and broadmindedness not often exhibited by women speakers." In November Mrs. Pankhurst was back in Wolverhampton making "a very capable speech" to an audience at the Baths Assembly Room. Dr. Helena Jones and Miss Joachim also spoke.

(14) David Simkin, Family History Research (28th October, 2022)

Maud Amalia Fanny Joachim was born in Paddington, London, on 1st August 1869 , the daughter of Ellen Margaret Smart (born 1843, London) and Henry Joachim (born circa 1824, Kittsee, Austria-Hungary), a "wool broker" who employed 4 clerks in 1871. Henry Joachim a "Subject of Hungary in the Empire of Austria" had become a "Naturalized British Subject" in 1856. Henry Joachim had married Ellen Margaret Smart in Hampstead, Middlesex, in 1863. The couple had 5 children - Gertrude Ellen (born 1865), Harold Henry (born 1868), Maud Amalia Fanny (born 1869), Dorothy Margaret (born 1874) and Nina Mary Joachim (born 1876). At the time of the 1881 Census, 56-year-old Henry Joachim was a "Retired (Wool) Merchant". Henry Joachim died in Kensington, London on 21st July 1897, aged 73.

At the time of the 1891 Census, 21-year-old Maud Joachim was living with her parents and three sisters - Gertrude, 25, Dorothy, 16, and Nina, 14, at No.13 Airlie Gardens, Kensington, London (together with four servants). No occupations are given for the four daughters. 65-year-old Henry Joachim is recorded as a "Retired Merchant ".

At the time of the 1901 Census, 31-year-old Maud Joachim was living in rooms at 6 Gray's Inn Place, Holborn, London.

In 1933, 64-year-old Miss Maud Joachim travelled to San Francisco, California, USA, with Miss Edith Storrs, aged 64.

At the time of the 1939 National Register, Maud Joachim was residing at 17, Somerset Terrace, St Pancras, London, and was living on "Private Means".

Maud Amelia (Amalia) Fanny Joachim of Mouse Cottage, Steyning, Sussex, died, aged 77, on 16th February 1947 leaving effects valued at £9,311.