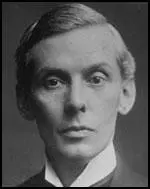

Christopher Addison

Christopher Addison, the son of Robert Addison (1838–1899), was born at the Willows Farm, Hogsthorpe, Lincolnshire, on 19th June 1869. His father, later moved to a much larger farm of 200 acres at Stallingborough, near Grimsby.

In 1882 Addison was sent off to Trinity College, Harrogate. An outstanding student, he won a place at Sheffield Medical School and he did his training at St Bartholomew's Hospital, where he graduated with honours.

Addison specialized in the field of human anatomy and in 1893 he gained his doctorate from the University of London. While a medical student he developed a strong interest in politics. His experiences as a doctor in London's East End, resulted in him becoming aware of the link between poverty and ill-health. Addison rejected his father's conservatism and joined the Liberal Party. His marriage to Isobel Mackinnon Gray, a Christian Socialist, in 1902, reinforced his radical political views.

Addison's research as a physiologist and anatomist resulted in him becoming a lecturer at the Royal College of Surgeons. He then moved to Charing Cross Hospital, where he later became dean. In 1904–6 he served as secretary of the Anatomical Society of Great Britain.

In 1907 Addison was adopted as Liberal Party candidate for the Hoxton division of Shoreditch. Addison was a follower of David Lloyd George, who as Chancellor of the Exchequer, had introduced the Old Age Pensions Act, that provided between 1s. and 5s. a week to people over seventy. To pay for these pensions Lloyd George had to raise government revenues by an additional £16 million a year. In 1909 Lloyd George announced what became known as the People's Budget. This included increases in taxation. Whereas people on lower incomes were to pay 9d. in the pound, those on annual incomes of over £3,000 had to pay 1s. 2d. in the pound. Lloyd George also introduced a new supertax of 6d. in the pound for those earning £5000 a year. Other measures included an increase in death duties on the estates of the rich and heavy taxes on profits gained from the ownership and sale of property. Other innovations in Lloyd George's budget included labour exchanges and a children's allowance on income tax.

The Conservatives, who had a large majority in the House of Lords, objected to this attempt to redistribute wealth, and made it clear that they intended to block these proposals. David Lloyd George reacted by touring the country making speeches in working-class areas on behalf of the budget and portraying the nobility as men who were using their privileged position to stop the poor from receiving their old age pensions. After a long struggle Lloyd George finally got his budget through parliament.

In the general election of January 1910, Addison captured Hoxton with a 338 majority. In the following general election that December he increased his majority to 694. With the House of Lords extremely unpopular with the British people, the Liberal government decided to take action to reduce its powers. The 1911 Parliament Act drastically cut the powers of the Lords. They were no longer allowed to prevent the passage of 'money bills' and it also restricted their ability to delay other legislation to three sessions of parliament.

Lloyd George's next reform was the 1911 National Insurance Act. This gave the British working classes the first contributory system of insurance against illness and unemployment. All wage-earners between sixteen and seventy had to join the health scheme. Each worker paid 4d a week and the employer added 3d. and the state 2d. In return for these payments, free medical attention, including medicine was given. Those workers who contributed were also guaranteed 7s. a week for fifteen weeks in any one year, when they were unemployed.

Addison, who was a member of the British Medical Association advisory committee on the bill, helped to get the measure passed in the House of Commons. As Kenneth O. Morgan has pointed out: "He (Addison) persuaded Lloyd George to frame concessions to the medical profession on the make-up of the new health committees, the terms of service under the new act, and the levels of remuneration. His campaigning did much to persuade the doctors to come to terms with Lloyd George's measure. From that time onwards, Lloyd George regarded the unassuming Dr Addison with high respect for his administrative skills and also his moral courage. They worked closely together in 1912–14 on behalf of a range of radical causes, health and housing, a new Medical Research Council, women's suffrage, Ireland, and the land taxes included in Lloyd George's budget of April 1914."

On 8th August 1914, Henry Asquith, the prime minister, appointed Addison as parliamentary secretary to the Board of Education. On the left-wing of the party, Addison had been initially opposed the foreign policy of Sir Edward Grey, but on the outbreak of the First World War, he gave the government his full support.

In May 1915 Addison was appointed as under-secretary to David Lloyd George, the new Minister of Munitions. Lloyd George gave Addison the job of costing contracts and in negotiations with arms manufacturers and the unions.

Addison supported Lloyd George's calls for military conscription. The coalition government was impressed with Lloyd George's abilities as a war minister and began to question the prime minister's leadership of the country during this crisis. In December, 1916, Addison and Lloyd George agreed to collaborate with the Conservatives in the cabinet to remove Herbert Asquith from power. When the plot was successful, Lloyd George appointed Addison as his new Minister of Munitions. Over the next six months he concentrated on the production of tanks that became a major factor in the war on the Western Front.

In July 1917, Winston Churchill became Minister of Munitions and Addison moved to the new Ministry of Reconstruction, concerned with post-war social and economic planning. This involved issues that he felt strongly about such as health and housing. The government accepted his proposal that it should establish a Ministry of Health.

An energetic war leader, David Lloyd George received a lot of credit for Britain's eventual victory over the Triple Alliance. Lloyd George's decision to join the Conservatives in removing Herbert Asquith in 1916 split the Liberal Party. In the 1918 General Election, many Liberals supported candidates who remained loyal to Asquith. Despite this, Lloyd George's Coalition group won 459 seats and had a large majority over the Labour Party and members of the Liberal Party who had supported Asquith.

In January 1919 Addison became president of the Local Government Board, with the responsibility of fulfilling the government's pledges of post-war reform. His first task was setting up a new Ministry of Health. He also introduced the Housing and Town Planning Act which launched a massive new programme of house building by the local authorities. This included a government subsidy to cover the difference between the capital costs and the income earned through rents from working-class tenants. As Kenneth O. Morgan has argued: "Controversy dogged the housing programme from the start. Progress in house building was slow, the private enterprise building industry was fragmented, the building unions were reluctant to admit unskilled workers, the local authorities could hardly cope with their massive new responsibilities, and Treasury policy overall was unhelpful. In addition, the costs of the Treasury subsidy began to soar, with uncontrolled prices of raw materials leading to apparently open-ended subventions from the state... However, Addison could ultimately claim that, in spite of all difficulties, 210,000 high-quality houses were built for working people, and that an important new social principle of housing as a social service had been enacted."

During the 1918 General Election campaign, David Lloyd George had promised comprehensive reforms to deal with education, housing, health and transport. However, he was now a prisoner of the Conservative Party who had no desire to introduce these reforms. Addison did what he could but he was a constant target for all those who felt the government was being too socialistic. His radicalism annoyed Lloyd George and in March 1921 he was moved to the anomalous post of minister without portfolio.

On 14th July 1922, Addison resigned from the government and in a speech in the House of Commons he denounced the government for its broken promises on social reform. Later, he wrote a pamphlet, The Betrayal of the Slums (1922), that was fierce attack on the policies of the Lloyd George government. Deprived of Addison's support, Lloyd George was forced from office in October 1922.

Addison, who stood as as an independent Liberal at Hoxton, finished a poor third in the 1922 General Election. In the 1924 General Election, he stood as a Labour candidate at Hammersmith South, but was unsuccessful. He now spent much time in writing, notably in producing two-volume reminiscences, Politics from Within (1924), and Practical Socialism (1926). Over the next few years Addison became primarily concerned with rural issues and advocated the nationalization of land.

In the 1929 General Election Addison was returned to the house as Labour MP for Swindon. The new prime minister, Ramsay MacDonald, appointed him as parliamentary secretary for agriculture. In June 1930 he succeeded Noel Buxton as minister for agriculture within the cabinet.

In 1930 Dr Charles Brook met Dr Ewald Fabian, the editor of Der Sozialistische Arzt and the head of Verbandes Sozialistischer Aerzte in Germany. Fabian said he was surprised that Britain did not have an organisation that represented socialists in the medical profession. Brook responded by arranging a meeting to take place on 21st September 1930 at the National Labour Club. As a result it was decided to form the Socialist Medical Association. Brook was appointed as Secretary of the SMA and Somerville Hastings became the first President. Addison joined the SMA as did Hyacinth Morgan, Reginald Saxton, Alex Tudor-Hart, Archie Cochrane, Christopher Addison, John Baird, Alfred Salter, Barnett Stross, Edith Summerskill, Robert Forgan and Richard Doll.

The Socialist Medical Association agreed a constitution in November 1930, "incorporating the basic aims of a socialised medical service, free and open to all, and the promotion of a high standard of health for the people of Britain". The SMA also committed itself to the dissemination of socialism within the medical profession. The SMA was open to all doctors and members of allied professions, such as dentists, nurses and pharmacists, who were socialists and subscribed to its aims. International links were established through the International Socialist Medical Association, based in Prague, an organisation that had been established by Dr Ewald Fabian.

As the new Minister of Agriculture, Christopher Addison launched a series of plans to increase food production. As one historian has pointed out: "He (Addison) pressed for import boards for cereal growers, quotas for production, and new powers for local authorities to take over land for cultivation. The most important of his proposals, however, was his Agricultural Marketing Bill of 1931. This measure, by raising the price for the producer, lowering it for the consumer, and fostering an overall expansion of agriculture through guaranteed prices and regular price reviews, was to inaugurate a long-term revolution in policy."

The election of the Labour Government coincided with an economic depression and Ramsay MacDonald was faced with the problem of growing unemployment. MacDonald asked Sir George May, to form a committee to look into Britain's economic problem. When the May Committee produced its report in July, 1931, it suggested that the government should reduce its expenditure by £97,000,000, including a £67,000,000 cut in unemployment benefits. MacDonald, and his Chancellor of the Exchequer, Philip Snowden, accepted the report but when the matter was discussed by the Cabinet, the majority, including Addison, voted against the measures suggested by the May Committee. Addison denounced it as a policy introduced to placate foreign bankers that would seriously erode standards of public health and education.

MacDonald was angry that his Cabinet had voted against him and decided to resign. When he saw George V that night, he was persuaded to head a new coalition government that would include Conservative and Liberal leaders as well as Labour ministers. Most of the Labour Cabinet totally rejected the idea and only three, Philip Snowden, Jimmy Thomas and John Sankey agreed to join the new government. MacDonald was determined to continue and his National Government introduced the measures that had been rejected by the previous Labour Cabinet.

In October, 1931, Ramsay MacDonald called an election. The 1931 General Election was a disaster for the Labour Party with only 46 members winning their seats. Addison was one of those Labour MPs who lost his seat. MacDonald, now had 556 pro-National Government MPs and had no difficulty pursuing the policies suggested by Sir George May.

In July 1936, Isabel Brown, at the Relief Committee for the Victims of Fascism in London, received a telegram from Socorro Rojo Internacional, based in Madrid, asking for help in the struggle against fascism in Spain. Brown approached the Socialist Medical Association about sending medical help to Republicans fighting in the Spanish Civil War.

Brown contacted Hyacinth Morgan, who in turn saw Dr Charles Brook. According to Jim Fyrth, the author of The Signal Was Spain: The Spanish Aid Movement in Britain, 1936-1939 (1986): "Morgan saw Dr Charles Brook, a general practitioner in South-East London, a member of the London County Council and founder and first Secretary of the Socialist Medical Association, a body affiliated to the Labour Party. Brook, who was a keen socialist and supporter of the people's front idea, though not sympathetic to Communism, was the main architect of the SMAC. At lunch-time on Friday 31 July, he saw Arthur Peacock, the Secretary of the National Trade Union Club, at 24 New Oxford Street. Peacock offered him a room at the club for a meeting the following afternoon, and office facilities for a committee."

Somerville Hastings, the President of the SMA, was keen to help the struggle against fascism and at a meeting on 8th August 1936 it was decided to form a Spanish Medical Aid Committee. Dr. Christopher Addison was elected President and the Marchioness of Huntingdon agreed to become treasurer. Other supporters included Leah Manning, George Jeger, Philip D'Arcy Hart, Frederick Le Gros Clark, Lord Faringdon, Arthur Greenwood, George Lansbury, Victor Gollancz, D. N. Pritt, Archibald Sinclair, Rebecca West, William Temple, Tom Mann, Ben Tillett, Eleanor Rathbone, Julian Huxley, Harry Pollitt and Mary Redfern Davies.

Leah Manning later recalled: "We had three doctors on the committee, one representing the TUC and I became its honorary secretary. The initial work of arranging meetings and raising funds was easy. It was quite common to raise £1,000 at a meeting, besides plates full of rings, bracelets, brooches, watches and jewellery of all kinds... Isabel Brown and I had a technique for taking collections which was most effective, and, although I was never so effective as Isabel (I was too emotional and likely to burst into tears at a moment's notice), I improved. In the end, either of us could calculate at a glance how much a meeting was worth in hard cash."

The First British Hospital was established by Kenneth Sinclair Loutit at Grañén near Huesca on the Aragon front. Other doctors, nurses and ambulance drivers at the hospital included Reginald Saxton, Alex Tudor-Hart, Archie Cochrane, Penny Phelps, Rosaleen Ross, Aileen Palmer, Peter Spencer, Patience Darton, Annie Murray, Julian Bell, Richard Rees, Nan Green, Lillian Urmston, Thora Silverthorne and Agnes Hodgson.

According to Jim Fyrth, the author of The Signal Was Spain: The Spanish Aid Movement in Britain, 1936-1939 (1986): "In the spring of 1937 the International Fund opened a 1,000-bed military hospital in a former training college at Onteniente, between Valencia and Alicante. With four operating theatres, eight wards, a blood transfusion unit and the most up-to-date equipment, it was described by Dr Morgan, the TUC Medical Adviser, as being the most efficient hospital in Spain."

On 22nd May 1937, Addison became the only Labour Party peer to be created by Neville Chamberlain, the new prime minister and went to the House of Lords as Baron Addison. Over the next two years he was a fierce critic of the government's foreign policy. This included the policy of non-intervention during the Spanish Civil War and its appeasement policy towards Adolf Hitler.

During the Second World War the influence of the Socialist Medical Association increased. In the 1945 General Election, twelve SMA members were elected to the House of Commons and there was now a concerted effort to persuade the government to introduce a National Health Service. It was hoped that Clement Attlee would appoint Dr. Edith Summerskill as Minister of Health. However, Attlee rejected this advice and Aneurin Bevan was appointed instead.

Although he was seventy-six years old, Attlee granted him the title, Viscount Addison of Stallingborough, and appointed him as leader of the House of Lords. According to Harold Wilson, members of the cabinet deferred to his experience. He took a particular interest in social welfare, and gave Aneurin Bevan backing with the creation of the NHS.

The House of Lords had a huge majority of hereditary Conservative Party peers at a time of a massive Labour Party majority in the House of Commons. Clement Attlee depended on Addison's statesmanship to get this acts of reform through Parliament.

After the Labour Party won a narrow majority in the 1950 General Election, Addison remained a member of his cabinet. He was among those who tried to persuade Aneurin Bevan and Harold Wilson not to resign from the government over health service charges in the spring of 1951. He left office after Winston Churchill and the Conservative Party won the 1951 General Election.

Christopher Addison died of cancer at his home, Neighbours, at Radnage, on 11th December 1951. He left two sons and two daughters.

Primary Sources

(1) Leah Manning, A Life for Education (1970)

We had three doctors on the committee, one representing the TUC and I became its honorary secretary. The initial work of arranging meetings and raising funds was easy. It was quite common to raise £1,000 at a meeting, besides plates full of rings, bracelets, brooches, watches and jewellery of all kinds... Isabel Brown and I had a technique for taking collections which was most effective, and, although I was never so effective as Isabel (I was too emotional and likely to burst into tears at a moment's notice), I improved. In the end, either of us could calculate at a glance how much a meeting was worth in hard cash."