Old Age Pensions Act

In 1902 George Barnes, General Secretary of the Amalgamated Society of Engineers, formed the National Committee of Organised Labour for Old Age Pension. Barnes spent the next three years travelling the country urging this social welfare reform. The measure was extremely popular and was an important factor in Barnes being able to defeat Andrew Bonar Law, the Conservative cabinet minister in the 1906 General Election. (1)

David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, in the government led by Herbert Asquith, made a speech had warned that if the Liberal Party did not pass radical legislation, at the next election, the working-class would vote for the Labour Party: "If at the end of our term of office it were found that the present Parliament had done nothing to cope seriously with the social condition of the people, to remove the national degradation of slums and widespread poverty and destitution in a land glittering with wealth, if they do not provide an honourable sustenance for deserving old age, if they tamely allow the House of Lords to extract all virtue out of their bills, so that when the Liberal statute book is produced it is simply a bundle of sapless legislative faggots fit only for the fire - then a new cry will arise for a land with a new party, and many of us will join in that cry." (2)

Old Age Pensions

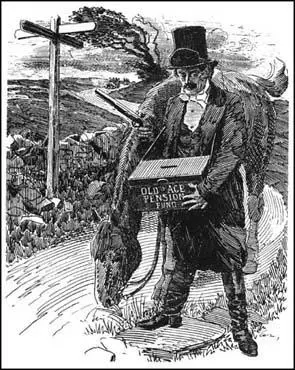

Lloyd George was also an opponent of the Poor Law in Britain. He was determined to take action that in his words would "lift the shadow of the workhouse from the homes of the poor". He believed the best way of doing this was to guarantee an income to people who were to old to work. Based on the ideas of Tom Paine that first appeared in his book Rights of Man, Lloyd George's proposed the introduction of old age pensions.

In a speech on 15th June 1908, he pointed out: "You have never had a scheme of this kind tried in a great country like ours, with its thronging millions, with its rooted complexities... This is, therefore, a great experiment... We do not say that it deals with all the problem of unmerited destitution in this country. We do not even contend that it deals with the worst part of that problem. It might be held that many an old man dependent on the charity of the parish was better off than many a young man, broken down in health, or who cannot find a market for his labour." (3)

However, the Labour Party was disappointed by the proposal. Along with the Trade Union Congress they had demanded a pension of at least five shillings a week for everybody of sixty or over, Lloyd George's scheme gave five shillings a week to individuals over seventy; and for couples the pension was to be 7s. 6d. Moreover, even among the seventy-year-olds not everyone was to qualify; as well as criminals and lunatics, people with incomes of more than £26 a year (or £39 a year in the case of couples) and people who would have received poor relief during the year prior to the scheme's coming into effect, were also disqualified." (4)

The People's Budget

To pay for these pensions Lloyd George had to raise government revenues by an additional £16 million a year. In 1909 Lloyd George announced what became known as the People's Budget. This included increases in taxation. Whereas people on lower incomes were to pay 9d. in the pound, those on annual incomes of over £3,000 had to pay 1s. 2d. in the pound. Lloyd George also introduced a new super-tax of 6d. in the pound for those earning £5,000 a year. Other measures included an increase in death duties on the estates of the rich and heavy taxes on profits gained from the ownership and sale of property. Other innovations in Lloyd George's budget included labour exchanges and a children's allowance on income tax. (5)

Archibald Primrose, Lord Rosebery, the former Liberal Party leader, stated that: "The Budget, was not a Budget, but a revolution: a social and political revolution of the first magnitude... To say this is not to judge it, still less to condemn it, for there have been several beneficent revolutions." However, he opposed the Budget because it was "pure socialism... and the end of all, the negation of faith, of family, of property, of Monarchy, of Empire." (6)

Lord Northcliffe, the owner of The Daily Mail and The Times, disliked the idea of paying higher taxes in order to help provide old age pensions and used all of his newspapers to criticize the measures in the budget. The Daily News launched an attack on the wealthy men opposed to the budget: "It is they who own the newspapers, and when we remember that The Times, The Daily Mail, and The Observer, not to mention a host of minor organs in London and the provinces, are all controlled by one man, it is easy to realise how vast a political power capital exerts by this means alone." (7)

Ramsay MacDonald argued that the Labour Party should fully support the budget. "Mr. Lloyd George's Budget, classified property into individual and social, incomes into earned and unearned, and followers more closely the theoretical contentions of Socialism and sound economics than any previous Budget has done." MacDonald went on to argue that the House of Lords should not attempt to block this measure. "The aristocracy... do not command the moral respect which tones down class hatreds, nor the intellectual respect which preserves a sense of equality under a regime of considerable social differences." (8)

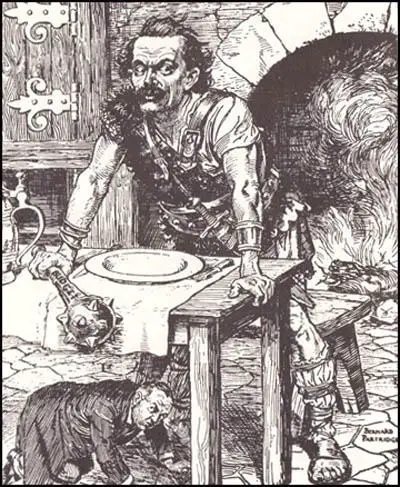

House of Lords

The Conservatives, who had a large majority in the House of Lords, objected to this attempt to redistribute wealth, and made it clear that they intended to block these proposals. Lloyd George reacted by touring the country making speeches in working-class areas on behalf of the budget and portraying the nobility as men who were using their privileged position to stop the poor from receiving their old age pensions. The historian, George Dangerfield, has argued that Lloyd George had created a budget that would destroy the House of Lords if they tried to block the legislation: "It was like a kid, which sportsmen tie up to a tree in order to persuade a tiger to its death." (9)

Asquith's strategy was to offer the peers the minimum of provocation and hope to finesse them into passing the legislation. Lloyd George had a different style and in a speech on 30th July, 1909, in the working-class district of Limehouse in London on the selfishness of rich men unwilling "to provide for the sick and the widows and orphans". He concluded his speech with the threat that if the peers resisted, they would be brushed aside "like chaff before us". (10)

Edward VII was furious and suggested to Asquith that Lloyd George was a "revolutionary" and a "socialist". Asquith explained that the support of the King was vital if the House of Lords was to be outmanoeuvred. Asquith explained to Lloyd George that the King "sees in the general tone, and especially in the concluding parts, of your speech, a menace to property and a Socialistic spirit". He added it was important "to avoid alienating the King's goodwill... and... what is needed is reasoned appeal to moderate and reasonable men" and not to "rouse the suspicions and fears of the middle class". (11)

David Lloyd George made another speech attacking the House of Lords on 9th October, 1909: "Let them realize what they are doing. They are forcing a Revolution. The Peers may decree a Revolution, but the People will direct it. If they begin, issues will be raised that they little dream of. Questions will be asked which are now whispered in humble voice, and answers will be demanded with authority. It will be asked why 500 ordinary men, chosen accidentally from among the unemployed, should override the judgment - the deliberate judgment - of millions of people who are engaged in the industry which makes the wealth of the country. It will be asked who ordained a few should have the land of Britain as a perquisite? Who made ten thousand people owners of the soil, and the rest of us trespassers in the land of our birth? Where did that Table of the law come from? Whose finger inscribed it? These are questions that will be asked. The answers are charged with peril for the order of things that the Peers represent. But they are fraught with rare and refreshing fruit for the parched lips of the multitude, who have been treading along the dusty road which the People have marked through the Dark Ages, that are now emerging into the light." (12)

It was clear that the House of Lords would block the budget. Asquith asked the King to create a large number of Peers that would give the Liberals a majority. Edward VII refused and his private secretary, Francis Knollys, wrote to Asquith that "to create 570 new Peers, which I am told would be the number required... would practically be almost an impossibility, and if asked for would place the King in an awkward position". (13)

In a speech on 21st February, 1910, Asquith outlined his plans for reform: "Recent experience has disclosed serious difficulties due to recurring differences of strong opinion between the two branches of the Legislature. Proposals will be laid before you, with convenient speed, to define the relations between the Houses of Parliament, so as to secure the undivided authority of the House of Commons over finance and its predominance in legislation." (14)

The Parliament Act

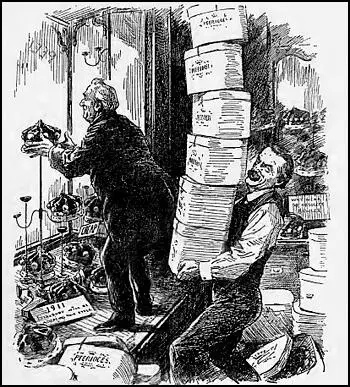

The Parliament Bill was introduced later that month. "Any measure passed three times by the House of Commons would be treated as if it had been passed by both Houses, and would receive the Royal Assent... The House of Lords was to be shorn absolutely of power to delay the passage of any measure certified by the Speaker of the House of Commons as a money bill, but was to retain the power to delay any other measure for a period of not less than two years." (15)

Edward VII died in his sleep on 6th May 1910. His son, George V, now had the responsibility of dealing with this difficult constitutional question. David Lloyd George had a meeting with the new king and had an "exceedingly frank and satisfactory talk about the political crisis". He told his wife that he was not very intelligent as "there's not much in his head". However, he "expressed the desire to try his hand at conciliation... whether he will succeed is somewhat doubtful." (16)

James Garvin, the editor of The Observer, argued it was time that the government reached a negotiated settlement with the House of Lords: "If King Edward upon his deathbed could have sent a last message to his people, he would have asked us to lay party passion aside, to sign a truce of God over his grave, to seek... some fair means of making a common effort for our common country... Let conference take place before conflict is irrevocably joined." (17)

A Constitutional Conference was established with eight members, four cabinet ministers and four representatives from the Conservative Party. Over the next six months the men met on twenty-one occasions. However, they never came close to an agreement and the last meeting took place in November. George Barnes, the Labour Party MP, called for an immediate creation of left-wing peers. However, when a by-election at Walthamstow suggested a slight swing to the Liberals, Asquith decided to call another General Election. (18)

David Lloyd George called on the British people to vote for a change in the parliamentary system: "How could anyone defend the Constitution in its present form? No country in the world would look at our system - no free country, I mean... France has a Senate, the United States has a Senate, the Colonies have Senates, but they are all chosen either directly or indirectly by the people." (19)

The Parliament Bill, which removed the peers' right to amend or defeat finance bills and reduced their powers from the defeat to the delay of other legislation, was introduced into the House of Commons on 21st February 1911. It completed its passage through the Commons on 15th May. A committee of the House of Lords then amended the bill out of all recognition. (20)

According to Lucy Masterman, the wife of Charles Masterman, the Liberal MP for West Ham North, that David Lloyd George had a secret meeting with Arthur Balfour, the leader of the Conservative Party. Lloyd George had bluffed Balfour into believing that George V had agreed to create enough Liberal supporting peers to pass a new Parliament Bill. (21)

Although a list of 249 candidates for ennoblement, including Thomas Hardy, Bertrand Russell, Gilbert Murray and J. M. Barrie, had been drawn up, they had not yet been presented to the King. After the meeting Balfour told Conservative peers that to prevent the Liberals having a permanent majority in the House of Lords, they must pass the bill. On 10th August 1911, the Parliament Act was passed by 131 votes to 114 in the Lords. (22)

Primary Sources

(1) J. R. Clynes, Memoirs (1937)

The Old Age Pensions Act was brought in by Mr. Lloyd George, and provided pensions for some half a million men and women over seventy years of age. But it was a well-recognised fact that the Liberals would never have supported these Bills in their final form, save for the pressure of Labour behind them, which made them fearful of losing their position as the professedly reformist Party in Parliament.

The Labour ranks were very angry and disappointed at the nervousness of the pension proposals. Pensions were to be paid at the rate of 5s. a week to persons over seventy years of age who could prove that they had no other income exceeding 10s. a week. If two pensioners lived together they were to receive only 7s. 6d. between them.

(2) David Lloyd George, Budget speech (29th April, 1909)

This is a war Budget. It is for raising money to wage implacable warfare against poverty and squalidness. I cannot help hoping and believing that before this generation has passed away, we shall have advanced a great step towards that good time, when poverty, and the wretchedness and human degradation which always follows in its camp, will be as remote to the people of this country as the wolves which once infested its forests.

(3) David Lloyd George, speech (9th October, 1909)

Let them realize what they are doing. They are forcing a Revolution. The Peers may decree a Revolution, but the People will direct it. If they begin, issues will be raised that they little dream of. Questions will be asked which are now whispered in humble voice, and answers will be demanded with authority. It will be asked why 500 ordinary men, chosen accidentally from among the unemployed, should override the judgment - the deliberate judgment - of millions of people who are engaged in the industry which makes the wealth of the country. It will be asked who ordained a few should have the land of Britain as a perquisite? Who made ten thousand people owners of the soil, and the rest of us trespassers in the land of our birth? Where did that Table of the law come from? Whose finger inscribed it?

These are questions that will be asked. The answers are charged with peril for the order of things that the Peers represent. But they are fraught with rare and refreshing fruit for the parched lips of the multitude, who have been treading along the dusty road which the People have marked through the Dark Ages, that are now emerging into the light."