Charles (Bebe) Rebozo

Charles (Bebe) Rebozo, the son of Cuban immigrants, was born on November 17, 1912, in Tampa, Florida. After leaving school Rebozo worked as a steward with Pan American Airways.

In 1931 Rebozo married Claire Gunn. The couple were divorced four years later. According to Claire Rebozo, the marriage was never consummated.

Rebozo eventually saved enough money to start his first business and in 1935 he opened Rebozo's Service Station and Auto Supplies. During the Second World War Rebozo became involved in the lucrative retread tire business. Rebozo invested these profits into a self-service laundry chain. He also began buying and selling land in Miami.

In December, 1951, George Smathers arranged for Rebozo to meet Richard Nixon. Rebozo took Nixon on a boat trip but the relationship got off to a bad start. Rebozo told Smathers that Nixon's "a guy who doesn't know how to talk, doesn't drink, doesn't smoke, doesn't chase women, doesn't know how to play golf, doesn't know how to play tennis... he can't even fish." However, the two men eventually became close friends.

The men spent so much time together that rumours circulated that the men were having a homosexual relationship. Bobby Baker claimed that Rebozo and Nixon were "close like lovers". According to one interview carried out by Anthony Summers in his book The Arrogance of Power: The Secret World of Richard Nixon, Rebozo was a member of Miami's homosexual community.

In 1952 Dwight Eisenhower selected Richard Nixon to be his vice president. As George Smathers later admitted that "Bebe's level of liking Nixon increased as Nixon's position increased". One of the ways that Rebozo helped Nixon was to obtain large campaign contributions from Howard Hughes.

Rebozo briefly remarried Claire Gunn. The marriage only lasted two years. Later he married Jane Lucke, his lawyer's secretary. In one interview, his wife said "Bebe's favourites are Richard Nixon, his cat - and then me." One of Rebozo's friends, Jake Jernigan, claimed that: "He (Rebozo) loved Nixon more than he loved anybody." Another friend said that "Bebe worshipped Nixon and hated Nixon's enemies".

Rebozo advised Richard Nixon about possible business investments. According to a FBI informant, the two men invested in Cuba when it was governed by the military dictator, Fulgencio Batista. Rebozo's business partner, Hoke Maroon, claimed that Nixon was also part-owner of the Coral Gables Motel.

In 1960 Nixon attempted to become president of the United States. Rebozo helped raise funds and paid for an investigation into the private life of Nixon's opponent, John F. Kennedy. Rebozo sent Nixon documents claiming that Kennedy had previously been married to Durie Malcolm. However, this story was untrue and despite this smear campaign against Kennedy, Nixon was defeated.

Rebozo became one of Nixon's closest political advisers. Rebozo also took a keen interest in Caribbean politics and had considerable business investments in the region. He therefore became one of the leading opponents of Fidel Castro after he gained power in Cuba. In 1961 Rebozo accompanied William Pawley on a secret mission to see Dominican Republic dictator Rafael Trujillo.

In 1964 Rebozo started his own financial institution, the Key Biscayne Bank. Nixon, who took part in the opening ceremony, held Savings Account No.1. The bank was used to fund a shopping centre for Cuban refugee merchants. The man brought in to manage this shopping centre, was Edgardo Buttari, Director for Social Assistance for the First Officers of Brigade 2506 (Bernardo de Torres was the Vice Director). Later, Richard Nixon appointed Buttari to a highly paid job in the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.

Rebozo also purchased land in Florida with a man called Richard Fincher. It was believed that Fincher worked as a front for Meyer Lansky. An examination of Fincher's telephone calls revealed that he was in regular contact with Carlos Marcello and Santo Trafficante. Vincent Teresa, a high-ranking mafioso, later admitted that he had used Rebozo's bank to launder stolen money.

After Richard Nixon became president in 1968, Rebozo was a regular visitor to the White House. However, he often used a false name and was not logged in by the Secret Service. Rebozo also negotiated deals on behalf of his business friends. One of the released White House tapes reveals Rebozo explaining that he could get "a quarter of a million at least" from a friend in return for an ambassadorship. Rebozo is also heard providing information that could be used to smear Nixon's political opponents.

Soon after he took office Nixon established Operation Sandwedge. Organized by H. R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman, the two main field officers were Jack Caulfield and Anthony Ulasewicz. Operation Sandwedge involved a secret investigation of Edward Kennedy. Caulfield later admitted that Ulasewicz’s reports on Kennedy went to three people: Nixon, Rebozo and Murray Chotiner.

In January, 1973, Frank Sturgis, E. Howard Hunt, Virgilio Gonzalez, Eugenio Martinez, Bernard L. Barker, Gordon Liddy and James W. McCord were convicted of conspiracy, burglary and wiretapping. Several of these men had links to the White House.

Rebozo was eventually dragged into the Watergate Scandal. During the investigation, a $100,000 donation from Howard Hughes that was meant for the Republican Party, was found in a safe-deposit box owned by Rebozo. The IRS now began a detailed look into Rebozo's financial affairs, with a focus on "misappropriation of campaign contributions, acceptance of money in exchange for favors by the Justice Department, distribution of Watergate hush money, and alleged diversion of campaign funds to Nixon's brothers and personal secretary."

The IRS investigation discovered that when Nixon took office his net worth was $307,000. During his first five years in the White House this sum had tripled to nearly $1 million. During the same period Rebozo's net worth went from $673,000 to $4.5 million. According to Jack Anderson, Nixon and Rebozo had both hidden money in Switzerland.

Rebozo escaped prosecution. One of the IRS investigators, Andy Baruffi, later claimed that "I was assigned to review the entire case file. We had Rebozo primarily on a straight up-and-down provable false statement charge. It was a dead-bang case. I believe a deal was made with the White House to kill the investigation."

In 1974 the staff of the Senate Watergate committee discovered that Charles Rebozo gave or lent part of a $100,000 campaign contribution to President Nixon's personal secretary Rose Mary Woods.

It was also discovered during the Watergate investigation that Rebozo had a business relationship with two of the burglars, Bernard L. Barker and Eugenio Martinez. Rebozo had also arranged for E. Howard Hunt to investigate Hoke Maroon, who had information about Nixon's early business investments in Cuba.

Charles Rebozo died on 8th May, 1998.

Primary Sources

(1) Kirkpatrick Sale, Yankees and Cowboys: The World Behind Watergate (1973).

Rebozo, the inscrutable man who is closest of all to Nixon the latest example of his intimacy being the donation of his hundred-thousand-dollar Bethesda home to Julie Nixon Eisenhower - deserves a somewhat closer examination here, for in some ways he personifies the Cowboy type. Rebozo, Cuban born of American parents, grew up in relative poverty, and at the start of World War II he was a gas-station operator in Florida. With the wartime tire shortage Rebozo got it into his head to expand his properties and start a recapping business, so he got a loan from a friend who happened to be on the local OPA tire board (a clear conflict of interest) and before long was the largest recapper in Florida. In 1951, he met Richard Nixon on one of the latter's trips to Miami and the two seem to have hit it off: both the same age, both quiet, withdrawn, and humorless, both aggressive success-hunters, both part of the new Southern-rim milieu.

Rebozo later expanded into land deals and in the early 1960s established the Key Biscayne Bank, of which he is president and whose first savings-account customer was Nixon. This bank in 1968 was the repository of stolen stocks, originally taken and channeled to the bank by organized crime sources. Rebozo clearly suspected there was something dubious about these stocks (he even told an FBI agent that he had called up Nixon's brother Donald to check on their validity), but he subsequently sold them for cash, even after an insurance company circular was mailed out to every bank listing them as stolen. Small wonder that the bank was thereupon sued by the company which had insured those stocks. (The case was eventually tried before a Nixon-appointed federal judge, James Lawrence King, who himself had some interesting banking experience as a director in 1964 of the Miami National Bank, cited by the New York Times [December 1, 1969] as a conduit for the Meyer Lansky syndicate's "shady money" from 1963 to 1967. King decided against the insurance company, but the case is now being appealed to a higher court.)

At about the same time as the stolen stocks episode came the shopping-center deal. Rebozo, by now a very rich man, still managed to get a loan out of the federal Small Business Administration-one of five which he somehow was lucky enough to secure in the 1960s, perhaps because of his friendship with ex-Senator George Smathers (who had been on the Senate Small Business Committee and who wrote the SBA to help Rebozo get another loan), or perhaps because the chief Miami officer of the SBA also happened to be a close friend of Rebozo's and a stockholder in his bank. This, coupled with the fact that Rebozo never fully disclosed his business dealings in making applications to the SBA, led Newsday in a prominent editorial, to denounce the SBA for "wheeling and dealing ... on Rebozo's behalf," and it led Representative Wright Patman to accuse the SBA publicly of wrongdoing in making Rebozo a "preferred customer."

With one of the SBA grants Rebozo proceeded to build an elaborate shopping center, to be leased to members of the rightwing Cuban exile community, and he let out the contracting bid for that to one "Big Al" Polizzi, a convicted black marketeer and a man named by the Federal Bureau of Narcotics as "one of the most influential members of the underworld in the United States."

Rather unsavory, all that, if not precisely criminal, and a rather odd career for an intimate of our moralistic president. But Nixon seems not to mind. In fact he has even gone in with Rebozo on at least one of his deals, a Florida real-estate venture called Fisher's Island, Inc., in which Nixon invested some $185,891 around 1962, and which he sold for exactly twice the value, $371,782, in 1969. It seems to have been a peculiarly shrewd deal, since the going rate for Fisher's Island stock had not in fact increased by a penny during those years and certainly hadn't doubled for anyone else-but happily for the stockholders, Nixon shortly thereafter signed a bill paving the way for $7 million worth of federal funds for the improvement of the Port of Miami, in which Fisher's island just happens to be located. In any case, that's small enough potatoes for a man in Nixon's position, and seems to reflect the fact that, no matter how many rich wheeler-dealers he has around him, Nixon himself is not out to make a vast personal fortune as his predecessor did.

But the unsavoriness surrounding Bebe Rebozo does not stop there. For in the mid-1960s Rebozo was also a partner in a Florida real-estate company with one Donald Berg, an acquaintance of Nixon's and the man from whom Nixon bought property in Key Biscayne less than a mile from the Florida White House. This same Donald Berg, who has been linked with at least one associate of mobster Meyer Lansky, has a background so questionable that after Nixon became president the Secret Service asked him to stop eating at Berg's Key Biscayne restaurant. Finally, according to Jack Anderson, Rebozo was "involved" in some of the real-estate deals of Bernard Barker, the former CIA operative who was the convicted payoff man for the Watergate operation in 1972.

(2) Anthony Summers, The Arrogance of Power: The Secret World of Richard Nixon (2000)

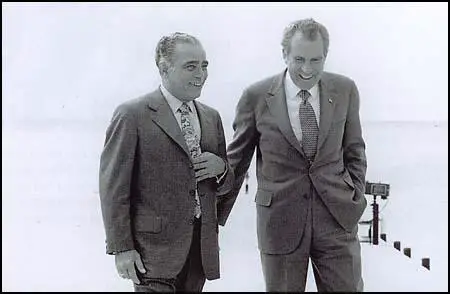

Rebozo was there to support Nixon at all the milestones on his political trail: in Florida after the 1952 election that made him vice president, after the major Republican setback in 1958, and at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles in 1960, when news came in that he had lost to John E Kennedy. In 1962, when Nixon ran for the governorship of California, Rebozo was there to comfort him in defeat. He traveled around the world with Nixon during the wilderness years of the mid-sixties and celebrated with him after he reached the White House in 1968. Nixon wrote his inaugural address while with Rebozo in Florida, and a rough calculation indicates that Rebozo was at his side one day in ten for the duration of the presidency.

The friendship had grown so close that Rebozo effectively had the run of the White House and his own phone number there. He flew on Air Force One, donning the coveted flying jacket bearing the presidential seal, cruised on the presidential yacht with Nixon and Kissinger, and picked movies for Nixon to watch at Camp David.

Despite his intimacy with the president, Rebozo long managed to keep a relatively low profile. Then came Watergate, and he was suddenly at the center of allegations about misuse of campaign contributions, gifts of jewelry for Pat Nixon, and secret presidential slush funds. Still he stayed close to Nixon, whenever possible under deep cover. He slipped into the White House without being logged in by the Secret Service and, using a false name, into Nixon's hotel suite during a trip to Europe.

Rebozo was one of the first to advise Nixon it was probably best that he resign. Afterward he frequently joined him in his exile in California, remaining a close companion through Nixon's years of rehabilitation until, by one account, he sat at Nixon's bedside during his final illness in 1994.

(3) Richard Nixon, The Memoirs of Richard Nixon (1978)

It was after five o'clock. Bebe Rebozo had come up from Florida that morning, and he was waiting for me outside my office when I emerged. We decided to go for a sail on the Sequoia. It was a warm spring evening, and as we sat out on the deck I gave him an outline of the Justice Department's case against Haldeman and Ehrlichman.

I asked him how much money I had in my account in his bank. I said that whatever happened, they had served me loyally and selflessly and I wanted to help with their legal expenses. Rebozo absolutely rejected the idea that I use my own savings. He said that he and Bob Abplanalp could raise two or three hundred thousand dollars. He added that he would have to give it to Haldeman and Ehrlichman in cash and privately, because he wouldn't be able to do the same thing for the others who also needed and deserved help.