William Gropper

William Gropper, the son of Harry and Jenny Gropper, was born in New York City on 3rd December 1897. His father was a Jewish immigrant, and despite the fact that he had a university degree and spoke eight languages, was forced to accept manual work and the family lived in poverty in New York's Lower East Side.

According to Joseph Anthony Gahn, the author of The America of William Gropper, Radical Cartoonist (1966), his father's situation had a major influence on the development of Gropper's political views. He was further radicalized by the death of his aunt in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, a disaster which resulted from locked doors in a New York sweatshop.

In 1912 Gropper began studying under Robert Henri and George Bellows at the Ferrer School in Harlem. The school had been founded by a group of anarchists that included Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman. Guest lecturers included writers and political activists such as Margaret Sanger, Jack London, and Upton Sinclair.

In 1917 joined the staff of the New York Tribune and over the next few years produced drawings for its Sunday edition. However, as a socialist, he mixed with radical cartoonists such as Alice Beach Winter, Cornelia Barns, Rockwell Kent, Art Young, Boardman Robinson, Robert Minor, Lydia Gibson, K. R. Chamberlain, George Bellows and Maurice Becker, who worked for the left-wing magazine, The Masses.

Gropper believed that the First World War had been caused by the imperialist competitive system. After the USA declared war on the Central Powers in 1917, the The Masses magazine came under government pressure to change its policy. When it refused to do this, the journal lost its mailing privileges. Gropper now joined forces with its former workers, including Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Crystal Eastman, Art Young, Robert Minor, Stuart Davis, Hugo Gellert, Maurice Becker, Lydia Gibson, Cornelia Barns and Louis Untermeyer to form the Liberator.

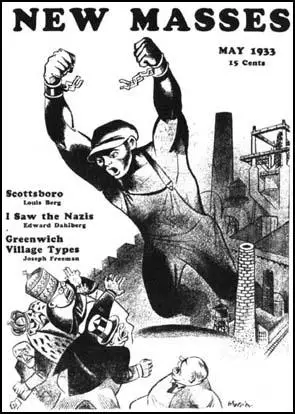

In 1922 the journal was taken over by Robert Minor and the American Communist Party and in 1924 was renamed as The Workers' Monthly. Many of the people who contributed to the original Liberator, including Gropper, were unhappy with this development and in 1926, they started their own journal, the New Masses.

Gropper also provided cartoons for The Revolutionary Age, a revolutionary socialist weekly edited by Louis C. Fraina and John Reed. Other drawings appeared in The Rebel Worker, a magazine of the Industrial Workers of the World. In 1921 he left the New York Tribune and became a freelance artist. It has been argued by one critic the "quiet, stocky William Gropper, a punch-packing cartoonist, is a still better painter. He paints as he draws, quickly and simply, without benefit of model, in reds, blues, yellows, whites."

After the failure of his relationship with Gladys Oaks he married Sophie Frankle in 1924. According to Time Magazine: "The two of them built their own nine-room stone house ("bourgeois as hell")" at Croton-on-Hudson. In 1925 he joined the New York World. Two years later he toured the Soviet Union with Sinclair Lewis and Theodore Dreiser.

Gropper was a great friend of John Reed, who died of typhus while in Moscow. In 1929 he joined with Hugo Gellert, Jacob Burck, Anton Refregier and Louis Lozowick, to establish the first John Reed Club. The group held classes and exhibitions in New York City. Later, these clubs were formed all over the country.

Gropper also painted and he had his first one-man show at the ACA Gallery in 1936. Gropper's work reflected a keen sense of social injustice and both his paintings and graphics were extremely influential during the Great Depression. He also attacked the growth of fascism in Germany, Italy and Japan and a cartoon of Emperor Hirohito that appeared in Vanity Fair in August 1935 caused a diplomatic incident with the Japanese government demanding an official apology.

After the Second World War Gropper became increasingly concerned with the growth of the extreme right in the United States. His attacks on Joseph McCarthy led to him being called before the House of Un-American Activities Committee in May 1953. Gropper, who was never a member of the American Communist Party, refused to answer any questions and claimed that the 5th Amendment of the United States Constitution gave him the right to do this.

Although blacklisted, Gropper, unlike the Hollywood Ten, who pleaded the 5th, was not imprisoned for taking this action. The experience resulted in him producing a series of fifty lithographs entitled the Caprichos.

Cécile Whiting has argued: "One of the most important illustrators for the American radical press, William Gropper sharpened his pen against potbellied politicians and bloodthirsty fascist leaders, while honoring the heroism of the worker and the rituals of Jewish life... Gropper experimented with a variety of techniques including pen and ink, lithography, etching, and painting. Despite his numerous works on canvas, however, Gropper was most gifted as a political illustrator."

In 1956 there was a major exhibition of his work at the Piccadilly Gallery in London. This was followed by the 1957 La Galerie del Frente Nacional des Artes exhibition in Mexico City. His last major work was the production of stained glass windows for Temple Har Zion, River Forest, Illinois.

William Gropper died from a myocardial infarction at Manhasset on 6th January 1977.

Primary Sources

(1) Max Eastman, Love and Revolution (1964)

There was one big difference between the Masses and the Liberator; in the latter we abandoned the pretense of being a co-operative. Crystal Eastman and I owned the Liberator, fifty-one shares of it, and we raised enough money so that we could pay solid sums for contributions.

The list of contributing editors, largely brought over from the Masses, reads as follows: Cornelia Barns, Howard Brubaker, Hugo Gellert, Arturo Giovannitti, Charles T. Hallinan, Helen Keller, Ellen La Motte, Robert Minor, John Reed, Boardman Robinson, Louis Untermeyer, Charles Wood, Art Young.

Later Claude McKay, the Negro poet, became an associate editor. At a New Year's party in 1921, we elected Michael Gold and William Gropper to the staff - two opposite poles of a magnet: Gropper as instinctively comic an artist as ever touched pen to paper, and Gold almost equally gifted with pathos and tears.

(2) Time Magazine (19th February, 1940)

Since 1920 Cartoonist William Gropper has been busy as a beaver, trying to gnaw down the capitalist system. One day that year Manhattan's Tribune rashly sent Gropper to caricature an I. W. W. rally. Instead, he became a convert. This week Manhattanites from Red to pink and some who just like pictures celebrated "20 Years of Bill Gropper" with a show of his recent paintings at the A. C. A. Gallery, a Gropper monograph (36 reproductions, text by self-taught fellow Artist Joe Jones), a rousing rally in Mecca Temple.

But this kind of hullabaloo could not obscure the most important fact: quiet, stocky William Gropper, a punch-packing cartoonist, is a still better painter. He paints as he draws, quickly and simply, without benefit of model, in reds, blues, yellows, whites. His masters are Breughel, Goya and Daumier. He does not disgrace them. Typically class-conscious canvases at the A. C. A. show: The Shoemaker, who is mending other men's shoes while barefoot himself; Brenda in a Tantrum, which shows 1939's Glamor Girl No. 1 streaming indignantly through the air; Art Patrons (see cut), a jut-jawed couple gazing bleakly at a picture they dislike. Without a message were Hallowe'en, Artist Gropper's small son Lee, in a gaudy pirate's costume, grinning out from under a cocked hat of newspapers, and The Kibitzer, an absorbed youth eying a poker player's royal flush.

For the Freiheit, Manhattan's Yiddish Communist paper, Bill Gropper does a daily cartoon, gets paid when the Freiheit can afford it. Without pay he cheerfully draws for the New Masses, the Sunday Worker. He makes his living free-lancing for capitalist publications, from Vogue to FORTUNE, painting murals for bars, hotels, Government buildings. His conservative employers run no risk of embarrassment. "To paint a mural that doesn't fit the place would be like painting swastikas in a synagogue," observes Artist Gropper. "If I were to paint a proletarian scene in a post office, Farley would jump out of his pants. My only interest, where I haven't got a free hand, is to do as good a job as possible."

William Gropper was born 42 years ago on Manhattan's lower East Side, on his way to school used to lug to a sweatshop the bundles of piecework sewing his mother did at home. Later he worked in a clothing store at $5 a week, took night art classes till he got his job on the Tribune. In Cropper's phrase he "fired the Tribune" after his I. W. W. conversion, became successively a labor organizer, oiler on a freight boat, itinerant sign painter.

In 1924 Bill Gropper married Bacteriologist Sophie Frankle. The two of them built their own nine-room stone house ("bourgeois as hell") at Croton-on-Hudson, N. Y. Soon after their marriage they had a year in Russia, where Gropper worked briefly on Pravda (official organ of the Communist Party), learned to call electric lights "Lenin lamps," had a grand time. Gene, their elder boy, was born in Paris on the return trip. To the New Masses went a cartoon by Artist Morris Pass of the proud father wheeling Gene in a baby carriage. Caption: "Made in the U. S. S. R."