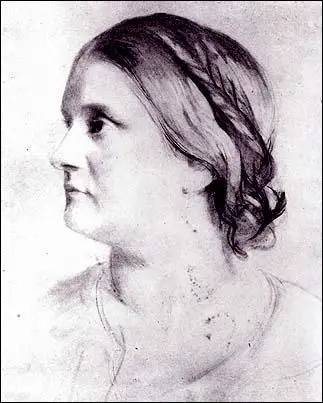

Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon

Barbara Leigh Smith, the daughter of Benjamin Leigh Smith and Anne Longden, was born near Robertsbridge, Sussex, on 8th April 1827. Her father came from a well-known unitarian radical family. Barbara's grandfather, had worked closely in Parliament with William Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson in their campaign against the slave-trade and had supported the French Revolution, whereas her great-grandfather had favoured the American colonists against the British government. The family was also related to Fanny Smith, the mother of Florence Nightingale. (1)

When Barbara was born her father was a member of the House of Commons and her mother, Anne Longden, was a seventeen-year old milliner who had been seduced by Smith. The birth created a scandal because the couple did not marry. Anne remained his common-law wife until she died of tuberculosis when Barbara was only seven years old. (2)

As her biographer, Pam Hirsch, has pointed out: "After the death of Anne Longden from tuberculosis in 1834, despite advice from some sections of his family to have the children discreetly brought up abroad, their father brought them up himself, first at Pelham Crescent, Hastings, and later at his London home, 5 Blandford Square, Marylebone. As the Leigh-Smith children were illegitimate they were not acknowledged by many of their Smith relations, including their aunt Fanny Nightingale and their first cousin, Florence Nightingale" (3)

Barbara Leigh-Smith and Education

The home of Benjamin Leigh-Smith was also a meeting place for fellow radicals and political refugees. This gave Barbara the opportunity to meet and make friends with a wide-range of different people involved in politics. Leigh Smith was an advocate of women's rights and treated Barbara the same way as her brothers. Barbara and her four brothers and sisters attended the local school where they were educated with working class children. (4)

In 1846 Barbara Leigh Smith met Elizabeth Rayner Parkes, both were born into Unitarian families, who supported progressive political opinions. Parkes was for example, the great-grand-daughter of Joseph Priestley, the scientist and radical philosopher. (5)

The two women became close friends and over the next few years spent many hours discussing women's rights."The two young women shared a desire for occupation and activity and a deep frustration at the restraints imposed by social convention. They wrote for local papers and radical periodicals and supported each other, often in emotional terms, as Parkes began to write poetry and Leigh Smith to study art. They became interested in the education of girls and increasingly aware of the existence of prostitution and the responsibilities of philanthropy." (6)

At the age of twenty-one, Benjamin Leigh-Smith gave all his children £300 a year. It was extremely unusual for fathers to treat their daughters this way and it gave Barbara the chance to be independent of her family. Barbara used some of this money to establish her own progressive school in London. Barbara selected Elizabeth Whitehead to be the school's headteacher. Before opening what later became known as the Portman Hall School, Barbara and Elizabeth made a special study of primary schools in London. It was decided to establish an experimental school that was undenominational, co-educational, and for children of different class backgrounds. (7)

In 1849 Barbara Leigh Smith wrote to Elizabeth Rayner Parkes: "I feel a mass of ideas and thoughts in my head and long for some expression, some letting out of, the restless spirit, in work for those who are ignorant. I feel quite oppressed sometimes with so much enjoyment of intellect (for I was all day yesterday seeing painting and pictures) and so I have been ever since I came up, I love and take keen delight in all this intellectual world but I feel still as if I had no right to enjoy so much while there is so much ignorance in the world and so many eyes shut up. Oh! When one really knows and understands a little of the misery in the world and its ignorance, is it not wicked to sit still and look at it? Ought one not to go out and help to fight it, even if ever so humbly. This is what is ever ringing in my head sometime loud and sometime soft but it is always there. But what is the use of talking. I am always thinking and talking, never acting." (8)

According to Ray Strachey, the author of The Cause: A History of the Women's Movement in Great Britain (1928) "Barbara Leigh-Smith... moved in legal, political, literary, and artistic circles from her early youth... Tall, handsome, generous and quite unselfconscious, she swept along, distracted only by the too great abundance of her interests and talents, and the too great outflowing of her sympathies." (9)

1857 Marriage and Divorce Act

Barbara Leigh-Smith took a keen interest in the legal rights of women. Ernest Sackville Turner has argued that the "Common Law of England, in the early part of the 19th century, granted a wife fewer rights than had been accorded to under the later Roman law, and hardly more than had been conceded to an African slave before emancipation... The husband... owned her body, her property, her savings, her personal jewels and her income, whether they lived together or separately." Turner goes on to point out, that the husband "could legally support his mistress on the earnings of his wife". (10)

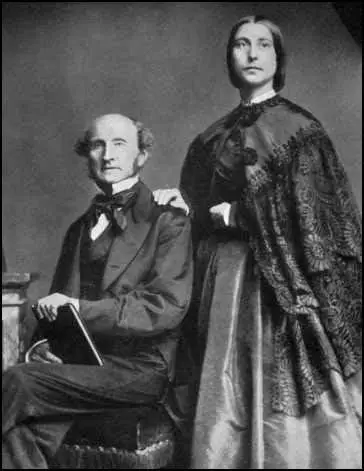

John Stuart Mill, the Radical MP for Westminster, was one of the few men who was willing to speak up for women: "She can acquire no property, but for the husband: the instant it becomes hers, even if by inheritance, it becomes ipso facto his... This is her legal state. And from this state she has no means to withdraw herself. If she leaves her husband she can take nothing with her, neither her children nor anything which is rightfully her own. If he chooses he can compel her to return by law, or by physical force; or he may content himself with seizing for his own use anything which she may earn or which may be given to her by her relations. It is only separation by a decree of a court of justice which entitles her to live apart without being forced back into the custody of an exasperated jailer." (11)

In 1850 a Royal Commission had recommended that the government took a look into the workings of the Divorce Law. Robert Rolfe, 1st Baron Cranworth, took up the challenge and when he was appointed Lord Chancellor he began to draw up new legislation. Caroline Norton, who had been involved in the passing of the Custody of Children Act, contacted Cranworth and requested that he included a clause that would ensure that wives could retain their own property after marriage. (12)

As part of her campaign Norton published the pamphlet, English Laws for Women in the Nineteenth Century (1854). She explained that after years of experiencing violence from her husband she was unable to obtain a divorce: "I consulted whether a divorce 'by reason of cruelty' might not be pleaded for me; and I laid before my lawyers the many instances of violence, injustice, and ill-usage, of which the trial was but the crowning example. I was then told that no divorce I could obtain would break my marriage; that I could not plead cruelty which I had forgiven; that by returning to Mr Norton I had 'condoned' all I complained of. I learnt, too, the law as to my children – that the right was with the father; that neither my innocence nor his guilt could alter it; that not even his giving them into the hands of a mistress, would give me any claim to their custody. The eldest was but six years old, the second four, the youngest two and a half, when we were parted. I wrote, therefore, and petitioned the father and husband in whose power I was, for leave to see them – for leave to keep them, till they were a little older. Mr Norton's answer was, that I should not have them; that if I wanted to see them, I might have an interview with them at the chambers of his attorney." (13)

Norton also wrote a letter to Queen Victoria complaining about the position of women in regards to divorce. "If her husband take proceedings for a divorce, she is not, in the first instance, allowed to defend herself. She has no means of proving the falsehood of his allegations... If an English wife be guilty of infidelity, her husband can divorce her so as to marry again; but she cannot divorce the husband, however profligate he may be. No law court can divorce in England. A special Act of Parliament annulling the marriage, is passed for each case. The House of Lords grants this almost as a matter of course to the husband, but not to the wife. In only four instances (two of which were cases of incest), has the wife obtained a divorce to marry again." (14)

Barbara Leigh-Smith joined the campaign, and published Brief Summary in Plain Language of the Most Important Laws Concerning Women (1854). It included the following passage: "A man and wife are one person in law; the wife loses all her rights as a single woman, and her existence is entirely absorbed in that of her husband. He is civilly responsible for her acts; she lives under his protection or cover, and her condition is called coverture. A woman's body belongs to her husband; she is in his custody, and he can enforce his right by a writ of habeas corpus." (15)

Langham Place Group

In 1854 Barbara Leigh Smith became friends with Elizabeth Garrett, Emily Davies and Bessie Rayner Parkes. She introduced the women to the works of Mary Wollstonecraft. Davies later wrote that the women were the first people "who sympathised with my feelings of resentment at the subjection of women". According to Margaret Forster, the author of Significant Sisters (1984), Davies was especially impressed with Barbara: "Although she was not at all the sort of person who adored anyone... but quickly came to adore Barbara. She even approved of how she dressed, in loose flowing clothes with her long blonde hair flowing down her back. She was, in every sense, a revelation." (16)

In 1855, together with a number of female artists and philanthropists, Barbara Bodichon and Harriet Grote established the Society of Female Artists (SFA). Other members included military artist, Elizabeth Thompson, watercolour artist Elizabeth Murray; opera singer Jenny Lind, the novelist Harriet Jane Trelawny, sculptor, Mary Thornycroft, the artist Margaret Tekusch and natural history illustrator, Augusta Innes Withers. (17)

The main objective of the SFA was to help women artists get their work exhibited. Pam Hirsch has pointed out: "The sudden increase in the number of women's paintings exhibited meant that they were inevitably of a variable standard, and some male critics took the opportunity to lament the allegedly low ability of paintings. The SFA gained mixed support from women artists themselves; some who were already successfully exhibiting at the Royal Academy ignored it, and some sent their large historical works to the Royal Academy and smaller works to the SFA." (18)

In 1857 Barbara Leigh Smith, Elizabeth Rayner Parkes, Louisa Garrett Smith, Elizabeth Garrett, Emily Davies, Helen Blackburn, Sophia Jex-Blake, Alice Westlake, Frances Power Cobbe, Jessie Boucherett and Emily Faithfull got together to form the Langham Place Group. Davies refused to be secretary because she thought it was prudent to keep her own name "out of sight, to avoid the risk of damaging my work in the education field by its being associated with the agitation for the franchise." Louisa Garrett Smith agreed to take on the role of secretary and be the organisation's figurehead. (19)

These women were therefore "at the core of the emerging mid-Victorian women's movement". (20) The group played an important role in campaigning for women to become doctors. They arranged for Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman in the United States to qualify as a doctor, to give a lecture entitled, "Medicine as a Profession for the Ladies". In 1862 they formed a committee to campaign for women's entry for university examinations, initially in support of Elizabeth Garrett, in her application to matriculate at London University. (21)

In March 1858 members of the Langham Place Group were involved in the publication of The English Woman's Journal. The journal was published by a limited company. The main shareholders were Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon and Emily Faithfull. The wealthy industrialist, Samuel Courtauld, who like Leigh Smith, was a Unitarian, also invested in the venture. The editor was Bessie Rayner Parkes. (22)

The journal was published monthly and cost 1 shilling. It was used to discuss female employment and equality issues concerning, in particular, manual or intellectual industrial employment, expansion of employment opportunities, and the reform of laws pertaining to the sexes. The offices in Langham Place became a centre for a wide variety of feminist enterprises. These included a women's reading-room and dining club, and offices for the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women. (23)

The proposed Marriage and Divorce Act was discussed at great length in 1857. William Ewart Gladstone, the future leader of the Liberal Party, was a strong opponent of the bill as he saw it as undermining the authority of the Church. He made seventy-three interventions against the bill, twenty-nine of them in the course of one protracted sitting. However, he was in a small minority and could only gain the support of a "few dozen votes". (24)

In the House of Lords, John Bird Sumner, the Archbishop of Canterbury and Henry Phillpotts, Bishop of Exeter, both supported the measure and became law in January, 1858. Its main purpose was to transfer jurisdiction on divorce from Parliament and the ecclesiastical courts to a new tribunal. This simplified proceedings and radically lowered divorce costs, thereby making it available to a larger section of the population. Actions for "criminal conversations" were abolished. (25)

The new law did not treat men and women on a equal basis. A man could divorce a woman if she was "guilty of adultery". However, the woman could only obtain a divorce if she could show that "her husband has been guilty of incestuous adultery, or of bigamy with adultery, or of rape, or of sodomy or bestiality, or of adultery coupled with such cruelty as without adultery would have entitled her to a divorce, or of adultery coupled with desertion, without reasonable excuse, for two years or upwards." (26)

Barbara Leigh-Smith was very critical of a legal system that failed to protect the property and earnings of married women. In 1857 Barbara wrote Women and Work where she argued that a married women's dependence on her husband was degrading. As a young woman Barbara had fallen in love with John Chapman, the editor of the Westminster Review. He proposed a "free-love" relationship with her, and she was deeply tempted despite his being already married. (27)

In the winter of 1856, owing to the ill health of one of her sisters, Isabella, Benjamin Leigh Smith took his three daughters to Algiers. There Barbara met Eugène Bodichon, a French physician and ethnographer. Barbara fell in love with Bodichon, who was seventeen years her senior. Her father initially disapproved but he eventually relented and the couple were married on 2nd July 1857. They went on honeymoon to America so that they could get obtain information on the subject of slavery and during their visit they had a meeting with Lucretia Mott. (28)

Her father's wedding gift was his house in Blandford Square. As a consequence of her marriage she spent half of each year in Algiers with her husband concentrating on her artistic career and half the year in England involved with social reform. In 1859 Barbara Bodichon bought a Moorish-style house on Mustapha Supérieure, overlooking the Bay of Algiers, which she named Campagne du Pavillon. It became a centre for English and French artistic and literary visitors to Algiers. As her husband hated London, in 1863 she built another house, Scalands Gate, in Robertsbridge. "Her husband was an eccentric man who neither learned English nor made much effort to endear himself to her family or friends. More positively, he accepted his wife's commitment to her career as an artist and her work as a social reformer." (29)

Kensington Society

In May 1865 a group of women in London led by Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon formed a discussion group called the Kensington Society. It was given this name because they held their meetings at 44 Phillimore Gardens in Kensington. It's founder members were the same women who formed the Langham Place Group and had been involved in the married women's property agitation and who had struggled to open local education examinations to girls. (30)

Membership was by personal invitation. The secretary, Emily Davies, brought together women "having more or less common interests and aims". Many were already friends, or were relatives of members. Others had been involved in the English Woman's Journal and had supported the campaign to open the Cambridge University local examinations to girls in 1864. Some met and shared ideas at the society for the first time. (31)

One of the founders of the group was Alice Westlake. On 18th March, 1865, Westlake wrote to Helen Taylor inviting her to join the group. She claimed that "none but intellectual women are admitted and therefore it is not likely to become a merely puerile and gossiping Society." (32) Westlake followed this with another letter on the 28th March: "There are very few few of the members whom you will know by name... the object of the Society is chiefly to serve as a sort of link, though a slight one, between persons, above the average of thoughtfulness and intelligence who are interested in common subjects, but who had not many opportunities of mutual intercourse." (33)

The Kensington Society had about fifty members, including Jessie Boucherett (writer), Emily Davies (educationalist), Francis Mary Buss (headmistress of North London Collegiate School), Dorothea Beale (principal of Cheltenham Ladies' College), Frances Power Cobbe (journalist), Anne Clough (educationalist), Alice Westlake (artist), Helen Taylor (educationalist), Elizabeth Garrett (medical student), Sophia Jex-Blake (medical student), Bessie Rayner Parkes (writer) and Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy (headmistress). (34)

Members of the Kensington Society were united by the opportunity to debate issues in a private, yet formal, setting. The women wanted practice in formal debating to build confidence for future public speaking. Some of the subjects discussed included: "What are the tests of originality?", "Is it desirable to employ emulation as a stimulus to education?" and "What form of government is most favourable to women?" In November 1865 the question was debated: "Is the extension of parliamentary suffrage to women desirable, and if so, under what conditions?" (35)

Nine of the eleven women who attended the early meetings were unmarried and were attempting to pursue a career in education or medicine. (36) Ann Dingsdale points out: "The annual subscription was half a crown. Questions for debate were issued four times a year and members might speak at meetings or submit written answers. Corresponding members submitted papers that were discussed by those who could attend (and who paid a further half-crown for that privilege). By conducting its debates in a private arena, with apparently unminuted discussions, the society encouraged a frank exchange of views." (37)

Helen Taylor was an important member of the Kensington Society because she was the step-daughter of John Stuart Mill, a philosopher who fully supported women's suffrage. In an article published in 1861 he argued: "In the preceding argument for universal, but graduated suffrage I have taken no account of difference of sex. I consider it to be as entirely irrelevant to political rights, as differences in height, or in the colour of the hair. All human beings have the same interest in good government; the welfare of all is alike affected by it, and they have equal need of a voice in it to secure their share of its benefits. If there be any difference women require it more than men, since being physically weaker, they are more dependent on law and society for protection." (38)

John Stuart Mill was invited by the Liberal Party to stand for the House of Commons in the 1865 General Election for Westminster. The Kensington Society saw this as an opportunity to promote the campaign for women's suffrage. In May 1866, Barbara Bodichon wrote to Mill's step-daughter, Helen Taylor: "I am very anxious to have some conversation with you about the possibility of doing something immediately towards getting women voters. I should not like to start a petition or make any movement without knowing what you and Mr J. S. Mill thought expedient at this time... Could you write a petition - which you could bring with you. I myself should propose to try simply for what we were most likely to get immediately." (39)

Helen Taylor replied the same day: "It seems to me that while a Reform Bill is under discussion and petitions are being presented to Parliament from different classes - asking for representation or protesting against disenfranchisement should say so, and that women who wish for political enfranchisement should say so, and that women not saying so now will be used against them in the future and delay the time of their enfranchisement.... I think the most important thing is to make a demand and commence the first humble beginnings of an agitation for which reasons can be given that are in harmony with the political ideas of English people in general. No idea is so universally accepted and acceptable in England as that taxation and representation ought to go together, and people in general will be much more willing to listen to the assertion that single women and widows of property have been overlooked and left out from the privileges to which their property entitles them, than to the much more startling general proposition that sex is not a proper ground for distinction in political rights." (40)

Helen Taylor stated that "If a tolerably numerously signed petition can be got up" her father would be willing to present it to Parliament." Two days later Barbara Bodichon replied that a small group including herself, Bessie Rayner Parkes, Elizabeth Garrett and Jessie Boucherett, had already started collecting signatures. (41) On receiving Taylor's draft petition, Bodichon commented it was too long and "it would be better to make it as short as possible and to state as few reasons as possible for what we want, everyone has something to say against the reasons." (42)

Women's Suffrage

In 1866 Lydia Becker heard Barbara Bodichon give a lecture on women's suffrage at a meeting in Manchester. She was immediately converted to the idea that women should have the vote and along with Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy, Josephine Butler, Eva Maclaren, Esther Roper and Eva Gore-Booth, helped establish the Manchester National Society for Women's Suffrage. (43)

In May 1866, Barbara Bodichon wrote to Helen Taylor about the need for votes for women. "I am very anxious to have some conversation with you about the possibility of doing something immediately toward giving women votes. I should like to start a petition or making any movement without knowing what you and Mr J.S. Mill thought expedient at this time. I have only just arrived in London from Algiers but I have already seen many ladies who are willing to take some steps for this cause." (44)

Taylor replied:"I think that while a reform bill is under discussion and petitions are being presented to Parliament from various causes - asking for representation or protesting against disfranchisement, it is very desirable that women who wish for political enfranchisement should say so." With the help of Jessie Boucherett, Emily Davies, Bessie Rayner Parkes and Elizabeth Garrett, she managed to persuade 1,499 women to sign the petition. (45)

On 20th May 1867, Mill made a speech in the House of Commons where he proposed that women should be granted the same rights as men. "We talk of political revolutions, but we do not sufficiently attend to the fact that there has taken place around us a silent domestic revolution: women and men are, for the first time in history, really each other's companions... when men and women are really companions, if women are frivolous men will be frivolous... the two sexes must rise or sink together." (46)

In less than a month the Kensington Society collected nearly 1,500 signatures (one important member, Dorothea Beale, refused to sign the petition. Helen replied when it was delivered: "My father will present the petition tomorrow (if that is still the wish of the ladies) and it should be sent to the House of Commons to arrive there before two p.m. tomorrow, Thursday June 7th directed to Mr Mill, and petition written on it. It is indeed a wonderful success. It does honour to the energy of those who have worked for it and promises well for the prospects of any future plan for furthering the same objects." (47)

On 7th June, 1867 Barbara Bodichon was ill and so Elizabeth Garrett and Emily Davies, escorted the great scroll to Westminster Hall and gave their petition to Henry Fawcett and John Stuart Mill, two MPs who supported universal suffrage. Mill, said, "Ah! this I can brandish with effect." (48) "The subject was almost entirely new to public consideration, and, as was natural, the feeling both in support of and in opposition to change was very strong. It would disrupt society, people said; it would destroy the home, and turn women into loathsome, self-assertive creatures no one could live with." (49)

Louisa Garrett Anderson later recalled: "John Stuart Mill agreed to present a petition from women householders… Elizabeth Garrett liked to be ahead of time, so the delegation arrived early in the Great Hall, Westminster, she with the roll of parchment in her arms. It made a large parcel and she felt conspicuous. To avoid attracting attention she turned to the only woman who seemed, among the hurrying men, to be a permanent resident in that great shrine of memories, the apple-woman, who agreed to hide the precious scroll under her stand; but, learning what it was, insisted first on adding her signature, so the parcel had to be unrolled again." (50)

During the debate on the issue, Edward Kent Karslake, the Conservative MP for Colchester, said in the debate that the main reason he opposed the measure was that he had not met one woman in Essex who agreed with women's suffrage. Lydia Becker, Helen Taylor and Frances Power Cobbe, decided to take up this challenge and devised the idea of collecting signatures in Colchester for a petition that Karslake could then present to parliament. They found 129 women resident in the town willing to sign the petition and on 25th July, 1867, Karslake presented the list to parliament. Despite this petition the Mill amendment to the 1867 Reform Act was defeated by 196 votes to 73. William Gladstone, was one of those who voted against the amendment. (51)

Barbara Bodichon fell out with other members of the Manchester National Society for Women's Suffrage over the issue of a women-only suffrage committee. Barbara disagreed with this strategy, believing that the loss of politically experienced men from their committee "might cost them ten years". As a consequence Barbara resigned from the suffrage committee in June 1867. However, her article, Reasons for and against the Enfranchisement of Women, was republished several times, in the propaganda campaign that followed. (52)

Members of the Kensington Society were very disappointed when they heard the news and they decided to dissolve the organisation early in 1868 and to establish the London Society for Women's Suffrage with the sole purpose of campaigning for women's suffrage. (47) Soon afterwards similar societies were formed in other large towns in Britain. Eventually seventeen of these groups joined together to form the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. (53)

Girton College

Although her main efforts went into the women's suffrage campaign, Bodichon continued her work to improve women's education. She joined forces with her old friend, Emily Davies, to campaign to obtain a university college for women and provided an initial donation of £1,000. Eventually they raised enough money to purchase Benslow, a house two miles outside the town. In 1873 Benslow House was opened as Girton College. (54)

The two women held different views on women's education. Emily Davies believed that the students should concentrate on traditional subjects such as classics and mathematics whereas Barbara Bodichon wanted a more radical approach to the curriculum. The two women also disagreed on student discipline. Davies favoured a strict regime compared to Barbara's more liberal approach. Students at Girton included Helena Swanwick, Eileen Power, Dora Russell, Margaret Llewelyn Davies, Margaret Cole and Dorothy Jewson. (55)

In 1875, Hertha Ayrton, the daughter of a Jewish watchmaker, wrote to Barbara Bodichon about her desire to study mathematics at Girton College. With the financial help of Bodichon and Taylor she was able to attend Girton between 1877 and 1881. According to Pam Hirsch Hertha "virtually became a daughter to her". (56)

When she was fifty-years of age, she was taken seriously ill and although she recovered she was left paralyzed. Although Bodichon retained her interest in women's rights, she was no longer able to take an active role in the movement. Bodichon remained an invalid until her death in Hastings on 11th June 1891. In her will Barbara Bodichon left a large sum of money to Girton College.

Primary Sources

(1) In a book she wrote in 1939, Louisa Garrett Anderson described how in 1859 a group of women under the leadership of Barbara Bodichon, began meeting at Langham Place in London.

In 1859 Barbara Bodichon had started an office in Langham Place to act as a bureau for helping women to find paid work. By 1861 Emily Davies, Elizabeth Garrett, Sophia Jex-Blake, Louise Smith, Emily Faithfull, Anne Proctor and many others met there. It was a centre of feminism. They were comrades and worked for a great end. The need felt by women for openings to paid employment was written in the office books. Louie Smith said to her hairdresser: "Surely, now, hairdressing is a calling suitable for women?' 'Impossible, madam, he said, 'I myself took a fortnight to learn it."

(2) Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon, Brief Summary in Plain Language of the Most Important Laws Concerning Women (1854)

Matrimony is a civil and indissoluble contract between a consenting man and woman of competent capacity...

A man and wife are one person in law; the wife loses all her rights as a single woman, and her existence is entirely absorbed in that of her husband. He is civilly responsible for her acts; she lives under his protection or cover, and her condition is called coverture.

A woman's body belongs to her husband; she is in his custody, and he can enforce his right by a writ of habeas corpus.

What was her personal property before marriage, such as money in hand, money at the bank, jewels, household goods, clothes, etc., becomes absolutely her husband's, and he may assign or dispose of them at his pleasure whether he and his wife live together or not.

A wife's chattels real (i.e., estates held during a term of years, or the next presentation to a church living, etc.) become her husband's by his doing some act to appropriate them; but, if the wife survives, she resumes her property.

Equity is defined to be a correction or qualification of the law, generally made in the part wherein it faileth, or is too severe. In other words, the correction of that wherein the law, by reason of its universality, is deficient. While the Common Law gives the whole of a wife's personal property to her husband, the Courts of Equity, when he proceeds therein to recover property in right of his wife, oblige him to make a settlement of some portion of it upon her, if she be unprovided for and virtuous.

If her property be under £200, or £10 a year, a Court of Equity will not interpose.

Neither the Courts of Common Law nor Equity have any direct power to oblige a man to support his wife,�the Ecclesiastical Courts (i.e., Courts held by the Queen's authority as governor of the Church, for matters which chiefly concern religion) and a Magistrate's court at the instance of her parish alone can do this.

A husband has a freehold estate in his wife's lands during the joint existence of himself and his wife, that is to say, he has absolute possession of them as long as they both live. If the wife dies without children, the property goes to her heir, but if she has borne a child, her husband holds possession until his death.

Money earned by a married woman belongs absolutely to her husband; that and all sources of income, excepting those mentioned above, are included in the term personal property.

By the particular permission of her husband she can make a will of her personal property, for by such a permission he gives up his right. But he may revoke his permission at any time before probate (i.e., the exhibiting and proving a will before the Ecclesiastical Judge having jurisdiction over the place where the party died.)

The legal custody of children belongs to the father. During the life-time of a sane father, the mother has no rights over her children, except a limited power over infants, and the father may take them from her and dispose of them as he thinks fit.

If there be a legal separation of the parents, and there be neither agreement nor order of Court, giving the custody of the children to either parent, then the right to the custody of the children (except for the nutriment of infants) belongs legally to the father.

A married woman cannot sue to be sued for contracts�nor can she enter into contracts except as the agent of her husband; that is to say, her word alone is not binding in law, and persons giving a wife credit have no remedy against her. There are some exceptions, as where she contracts debts upon estates settled to her separate use, or where a wife carries on trade separately, according to the custom of London, etc.

A husband is liable for his wife's debts contracted before marriage, and also for her breaches of trust committed before marriage.

Neither a husband nor a wife can be witnesses against one another in criminal cases, not even after the death or divorce of either.

A wife cannot bring actions unless the husband's name is joined.

As the wife acts under the command and control of her husband, she is excused from punishment for certain offences, such as theft, burglary, house-breaking, etc., if committed in his presence and under his influence. A wife cannot be found guilty of concealing her felon husband or of concealing a felon jointly with her husband. She cannot be found guilty of stealing from her husband or of setting his house on fire, as they are one person in law. A husband and wife cannot be found guilty of conspiracy, as that offence cannot be committed unless there are two persons.

(3) In her book Women's Suffrage (1911), Millicent Garrett Fawcett described the organisation of a petition on women's suffrage.

In 1866 a little committee of workers had been formed to promote a parliamentary petition from women in favour of women's suffrage. It met in the house of Miss Elizabeth Garrett (now Mrs. Garrett Anderson) and included Mrs. Bodichon, Miss Emily Davies, Miss Rosamond Davenport Hill and other well-known women.

(4) In 1866 Barbara Bodichon, Emily Davies, Elizabeth Garrett and Dorothea Beale organised a petition in favour of women's suffrage. Louisa Garrett Anderson explained what happened on the day the petition was presented to Parliament.

John Stuart Mill agreed to present a petition from women householders… On 7th June 1866 the petition with 1,500 signatures was taken to the House of Commons. It was in the name of Barbara Bodichon and others, but some of the active promoters could not come and the honour of presenting it fell to Emily Davies and Elizabeth Garrett…. Elizabeth Garrett liked to be ahead of time, so the delegation arrived early in the Great Hall, Westminster, she with the roll of parchment in her arms. It made a large parcel and she felt conspicuous. To avoid attracting attention she turned to the only woman who seemed, among the hurrying men, to be a permanent resident in that great shrine of memories, the apple-woman, who agreed to hide the precious scroll under her stand; but, learning what it was, insisted first on adding her signature, so the parcel had to be unrolled again.

(5) Louisa Martindale became interested in the subject of women's rights in the 1860s and eventually became a leading figure in the Sussex Women's Liberal Association. Louisa Martindale wrote about her mother's involvement in the movement in her book From One Generation to Another (1944).

In the 1860s mother began reading widely, and learnt how Mary Wollstonecraft had vindicated the rights of women in burning words, how Caroline Norton had struggled for her rights over her children, and how Emily Davies and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson showed what determination was needed by young women who wished for academic or professional education. She read Barbara Bodichon's Englishwomen's Journal, which discovered and exposed the obstacles to the employment of educated women, and she learnt about Florence Nightingale and her work on the vast problem of nursing and sanitary administration. In the 1860s women realised that the only way to civil rights, higher education, and equal status lay through the parliamentary franchise.

(6) Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon, Reasons for and against the Enfranchisement of Women (1867)

That a respectable, orderly, independent body in the State should have no voice, and no influence recognised by the law, in the election of the representatives of the people, while they are otherwise acknowledged as responsible citizens, are eligible for many public offices, and required to pay all taxes, is an anomaly which seems to require some explanation. Many people are unable to conceive that women can care about voting. That some women do care, has been proved by the Petitions presented to Parliament. I shall try to show why some care—and why those who do not ought to be made to care.

There are now a very considerable number of open‐minded, unprejudiced people, who see no particular reason why women should not have votes, if they want them; but, they ask, what would be the good of it? What is there that women want which male legislators are not willing to give? And here let me say at the outset, that the advocates of this measure are very far from accusing men of deliberate unfairness to women. It is not as a means of extorting justice from unwilling legislators that the franchise is claimed for women. In so far as the claim is made with any special reference to class interests at all, it is simply on the general ground that under a representative government, any class which is not represented is likely to be neglected. Proverbially, what is out of sight is out of mind; and the theory that women, as such, are bound to keep out of sight, finds its most emphatic expression in the denial of the right to vote. The direct results are probably less injurious than those which are indirect; but that a want of due consideration for the interests of women is apparent in our legislation, could very easily be shown. To give evidence in detail would be a long and invidious task. I will mention one instance only, that of the educational endowments all over the country. Very few people would now maintain that the education of boys is more important to the State than that of girls. But as a matter of fact, girls have but a very small share in educational endowments. Many of the old foundations have been reformed by Parliament, but the desirableness of providing with equal care for girls and boys has very seldom been recognised. In the administration of charities generally, the same tendency prevails to postpone the claims of women to those of men.

Among instances of hardship traceable directly to exclusion from the franchise and to no other cause, may be mentioned the unwillingness of landlords to accept women as tenants. Two large farmers in Suffolk inform me that this is not an uncommon case. They mention one estate on which seven widows have been ejected, who, if they had had votes, would have been continued as tenants.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)