Langham Place Group

The origin of the Langham Place Group lay in the close friendship which developed between Elizabeth Rayner Parkes and Barbara Leigh Smith. In 1846 Parkes met Smith, both were born into Unitarian families, who supported progressive political opinions. Parkes was for example, the great-grand-daughter of Joseph Priestley, the scientist and radical philosopher. (1)

The two women became close friends and over the next few years spent many hours discussing women's rights."The two young women shared a desire for occupation and activity and a deep frustration at the restraints imposed by social convention. They wrote for local papers and radical periodicals and supported each other, often in emotional terms, as Parkes began to write poetry and Leigh Smith to study art. They became interested in the education of girls and increasingly aware of the existence of prostitution and the responsibilities of philanthropy." (2)

At the age of twenty-one, Benjamin Leigh Smith gave all his children £300 a year. It was extremely unusual for fathers to treat their daughters this way and it gave Barbara the chance to be independent of her family. In 1848 Barbara used some of this money to establish her own progressive school in London. Barbara selected Elizabeth Whitehead to be the school's headteacher. Before opening what later became known as the Portman Hall School, Barbara and Elizabeth made a special study of primary schools in London. It was decided to establish an experimental school that was undenominational, co-educational, and for children of different class backgrounds. (3)

According to Ray Strachey, the author of The Cause: A History of the Women's Movement in Great Britain (1928) "Barbara Leigh-Smith... moved in legal, political, literary, and artistic circles from her early youth... Tall, handsome, generous and quite unselfconscious, she swept along, distracted only by the too great abundance of her interests and talents, and the too great outflowing of her sympathies." (4)

Caroline Norton, who had been involved in the passing of the Custody of Children Act, including a clause that would ensure that wives could retain their own property after marriage. (5) Barbara Leigh-Smith joined the campaign, and published Brief Summary in Plain Language of the Most Important Laws Concerning Women (1854). It included the following passage: "A man and wife are one person in law; the wife loses all her rights as a single woman, and her existence is entirely absorbed in that of her husband. He is civilly responsible for her acts; she lives under his protection or cover, and her condition is called coverture. A woman's body belongs to her husband; she is in his custody, and he can enforce his right by a writ of habeas corpus." (6)

In 1849 Barbara Leigh Smith wrote to Elizabeth Rayner Parkes: "I feel a mass of ideas and thoughts in my head and long for some expression, some letting out of, the restless spirit, in work for those who are ignorant. I feel quite oppressed sometimes with so much enjoyment of intellect (for I was all day yesterday seeing painting and pictures) and so I have been ever since I came up, I love and take keen delight in all this intellectual world but I feel still as if I had no right to enjoy so much while there is so much ignorance in the world and so many eyes shut up. Oh! When one really knows and understands a little of the misery in the world and its ignorance, is it not wicked to sit still and look at it? Ought one not to go out and help to fight it, even if ever so humbly. This is what is ever ringing in my head sometime loud and sometime soft but it is always there. But what is the use of talking. I am always thinking and talking, never acting." (7)

In 1854 Barbara Leigh Smith became friends with Elizabeth Garrett, Emily Davies and Bessie Rayner Parkes. She introduced the women to the works of Mary Wollstonecraft. Davies later wrote that the women were the first people "who sympathised with my feelings of resentment at the subjection of women". According to Margaret Forster, the author of Significant Sisters (1984), Davies was especially impressed with Barbara: "Although she was not at all the sort of person who adored anyone... but quickly came to adore Barbara. She even approved of how she dressed, in loose flowing clothes with her long blonde hair flowing down her back. She was, in every sense, a revelation." (8)

In 1857 Barbara Leigh Smith, Elizabeth Rayner Parkes, Louisa Garrett Smith, Elizabeth Garrett, Emily Davies, Helen Blackburn, Sophia Jex-Blake, Alice Westlake, Frances Power Cobbe, Jessie Boucherett and Emily Faithfull got together to form the Langham Place Group. Davies refused to be secretary because she thought it was prudent to keep her own name "out of sight, to avoid the risk of damaging my work in the education field by its being associated with the agitation for the franchise." Louisa Garrett Smith agreed to take on the role of secretary and be the organisation's figurehead. (9)

These women were therefore "at the core of the emerging mid-Victorian women's movement". (10) The group played an important role in campaigning for women to become doctors. They arranged for Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman in the United States to qualify as a doctor, to give a lecture entitled, "Medicine as a Profession for the Ladies". In 1862 they formed a committee to campaign for women's entry for university examinations, initially in support of Elizabeth Garrett, in her application to matriculate at London University. (11)

In March 1858 members of the Langham Place Group were involved in the publication of The English Woman's Journal. The journal was published by a limited company. The main shareholders were Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon and Emily Faithfull. The wealthy industrialist, Samuel Courtauld, who like Leigh Smith, was a Unitarian, also invested in the venture. The editor was Bessie Rayner Parkes. (12)

The journal was published monthly and cost 1 shilling. It was used to discuss female employment and equality issues concerning, in particular, manual or intellectual industrial employment, expansion of employment opportunities, and the reform of laws pertaining to the sexes. The offices in Langham Place became a centre for a wide variety of feminist enterprises. These included a women's reading-room and dining club, and offices for the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women. (13)

In 1859 Emily Faithfull, Jessie Boucherett, Bessie Rayner Parkes and Barbara Leigh Smith formed the Society for the Promotion of the Employment of Women. This caused conflict within the Langham Place Group as Elizabeth Rayner Parkes condemned the work of married women outside the home, though Boucherett and Faithfull argued that "every woman should be free to support herself by the use of whatever faculties God has given her, without obstruction by prejudice or legislation". (14)

As Jane Rendall pointed out: "These liberal feminists recognized a potential conflict with orthodox political economy, often invoked against women's work as depressing the wages of men in free competition. Some, like Boucherett, were prepared to face the consequences of a free market in labour. Parkes and others suggested ways in which association and co-operation among women might moderate the harshness of the free market, though some proposals looked more like philanthropy than co-operation." (15)

The work of the Langham Place group was given added publicity by the success of two papers given at the conference of the Social Science Association held in Bradford in October 1859. Elizabeth Rayner Parkes read a paper, to which Barbara Leigh Smith contributed, on "The Market for Educated Female Labour" and Jessie Boucherett delivered "The Industrial Employments of Women". (16) Boucherett wrote to Smith claiming: "The whole kingdom is ringing with our Bradford Paper, and subscriptions pouring in at the EWJ (English Woman's Journal) office... What a crown to our long struggle begun 10 years ago.... It is a long struggle which is beginning to tell; and the having an organisation in which to receive the Public Interest." (17)

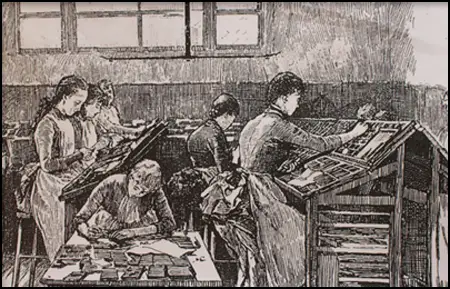

On 25th March 1860, Emily Faithfull established the Victoria Press at Great Coram Street, London. She invested her own capital in the press and had the financial backing of another committee member of the Society for the Promotion of the Employment of Women. The Victoria Press printed The English Woman's Journal. The press employed at the outset women compositors, despite the trade restrictions practised by men, but the venture was to remain an irritant to many compositors and others in the printing trade. (18) Elizabeth Rayner Parkes wrote in her diary: "They will employ at least 6 girls; so here are women in the trade at last! One dream of my life!" (19)

The Langham Group were not in total agreement about certain issues. Emily Faithfull was involved in a scandalous divorce case, and religious differences between Catholic, Anglican, and Unitarian perspectives were surfacing. There were conflicts as to whether their work should continue to be primarily women only, as Elizabeth Rayner Parkes believed, or play its part in mixed campaigns and voluntary associations, as Emily Davies argued. (20)

The women also held different opinions on women's suffrage. For example, Emily Faithfull never became involved in the struggle for the vote. In an interview she gave near the end of her life, Faithfull said "I am strongly in favour of it (women's suffrage), but I do not give it the enormous prominence some do. I do not believe it is the end and aim of all things. In politics I am a Conservative... I am not in favour of socialists or Revolutionists, nor do I wish to see the Empire dismembered". (21)

In May 1865 a group of women in London formed a discussion group called the Kensington Society. It was given this name because they held their meetings at 44 Phillimore Gardens in Kensington. It's founder members were the same women who formed the Langham Place Group and had been involved in the married women's property agitation and who had struggled to open local education examinations to girls. (22)

Membership was by personal invitation. The secretary, Emily Davies, brought together women "having more or less common interests and aims". Many were already friends, or were relatives of members. Others had been involved in the English Woman's Journal and had supported the campaign to open the Cambridge University local examinations to girls in 1864. Some met and shared ideas at the society for the first time. (23)

One of the founders of the group was Alice Westlake. On 18th March, 1865, Westlake wrote to Helen Taylor inviting her to join the group. She claimed that "none but intellectual women are admitted and therefore it is not likely to become a merely puerile and gossiping Society." (24) Westlake followed this with another letter on the 28th March: "There are very few few of the members whom you will know by name... the object of the Society is chiefly to serve as a sort of link, though a slight one, between persons, above the average of thoughtfulness and intelligence who are interested in common subjects, but who had not many opportunities of mutual intercourse." (25)

The Kensington Society had about fifty members, including Barbara Bodichon (artist), Jessie Boucherett (writer), Emily Davies (educationalist), Francis Mary Buss (headmistress of North London Collegiate School), Dorothea Beale (principal of Cheltenham Ladies' College), Frances Power Cobbe (journalist), Anne Clough (educationalist), Alice Westlake (artist), Helen Taylor (educationalist), Elizabeth Garrett (medical student), Sophia Jex-Blake (medical student), Bessie Rayner Parkes (writer) and Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy (headmistress). (26)

Members of the Kensington Society were united by the opportunity to debate issues in a private, yet formal, setting. The women wanted practice in formal debating to build confidence for future public speaking. Some of the subjects discussed included: "What are the tests of originality?", "Is it desirable to employ emulation as a stimulus to education?" and "What form of government is most favourable to women?" In November 1865 the question was debated: "Is the extension of parliamentary suffrage to women desirable, and if so, under what conditions?" (27)

Primary Sources

(1) Barbara Leigh Smith, letter to Elizabeth Rayner Parkes (1849)

I feel a mass of ideas and thoughts in my head and long for some expression, some letting out of, the restless spirit, in work for those who are ignorant. I feel quite oppressed sometimes with so much enjoyment of intellect (for I was all day yesterday seeing painting and pictures) and so I have been ever since I came up, I love and take keen delight in all this intellectual world but I feel still as if I had no right to enjoy so much while there is so much ignorance in the world and so many eyes shut up. Oh! When one really knows and understands a little of the misery in the world and its ignorance, is it not wicked to sit still and look at it? Ought one not to go out and help to fight it, even if ever so humbly. This is what is ever ringing in my head sometime loud and sometime soft but it is always there. But what is the use of talking. I am always thinking and talking, never acting.

(2) Jessie Boucherett, letter to Barbara Leigh Smith (17th November 1859)

The whole kingdom is ringing with our Bradford Paper, and subscriptions pouring in at the EWJ office... What a crown to our long struggle begun 10 years ago.... It is a long struggle which is beginning to tell; and the having an organisation in which to receive the Public Interest.

(3) Jane Rendall, Langham Place Group (22nd September 2005)

Langham Place group (active 1857–1866), brought together a small number of determined middle-class women to campaign on a variety of fronts for the improvement of the situation of women. In identifying their own needs they also began to define a cautious liberal feminist politics, which in negotiating the tensions of class and gender bequeathed a legacy of moderation and respectability to the next feminist generation. The group took its name from the office of the English Woman's Journal, launched in 1858, and established in December 1859 at 19 Langham Place, London.

The origin of the group lay in the close friendship which developed from the late 1840s between Barbara Leigh Smith and Elizabeth Rayner Parkes. Both were born into progressive Unitarian families, at the centre of dissenting and radical opinion and politics. The two young women shared a desire for occupation and activity and a deep frustration at the restraints imposed by social convention. They wrote for local papers and radical periodicals and supported each other, often in emotional terms, as Parkes began to write poetry and Leigh Smith to study art. They became interested in the education of girls and increasingly aware of the existence of prostitution and the responsibilities of philanthropy. They were influenced among others by the older Anna Jameson, though her belief in ‘the communion of labour’ between the complementary but different roles of men and women was more limited than their own approaches to feminist politics...

The ideas and the practice of the Langham Place group were pervaded by the complexities of liberal feminism. Although some individuals led unconventional lives, there was no public confrontation of the sexual double standard or codes of propriety. Accepting the importance of sexual difference, members of the group argued for the distinctive and particular contribution which women could make to society. Conscious of women's need for autonomy, they asserted the need for equal educational provision and for unfettered access to the employment market, though often with qualifications and ambiguities. Their analyses and their solutions were derived from the perspectives of the reforming middle classes, as was the concept of female citizenship with which, as individuals, they mostly continued to work.

(4) Felicity Hunt, Emily Faithfull (21st May 2009)

The Early on members of the group began to explore new openings for respectable employment for all classes of women, and in 1859 they formed the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women. One possibility considered was that of compositor, a skilled trade almost wholly confined to men, already effectively unionized and jealously guarded against both unskilled machine operators and any incursions by women. Bessie Parkes bought a small printing press, and she and Emily Faithfull employed a compositor, Austin Holyoake (brother of George Jacob Holyoake), to give instruction in composing. On the basis of this experience they concluded that composing could be a suitable occupation for women. To this end, on 25 March 1860, Emily Faithfull opened the Victoria Press at Great Coram Street, London. She invested her own capital in the press and had the financial backing of another committee member of the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women, G. W. Hastings.

The press employed at the outset some semi-experienced female compositors, who existed despite the trade restrictions practised by men, but the venture was to remain an irritant to many compositors and others in the printing trade. It was nevertheless a commercial success, although the women compositors only composed and proof-read, unlike later women printers working for the Women's Printing Society (founded in 1876 by Emma Paterson's Women's Protective and Provident League, with which Emily Faithfull was also associated), who also carried out both imposition and ‘making up' (making up the type into pages and placing them in the iron frame or chase for printing). Initially Emily Faithfull both printed and published, one of her earliest works being The Victoria Regia (1861), edited by Adelaide Ann Procter. The work and the press attracted the approval of Queen Victoria, and in that same year Emily Faithfull was appointed by royal warrant 'Printer and Publisher in Ordinary to Her Majesty'. In 1863 she was the founder editor of the Victoria Magazine, a monthly periodical, to which she contributed until it ceased publication in 1880. The press published the Transactions of the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science from 1860 to 1864. Emily Faithfull was connected with the association, and remained for the rest of her life actively engaged in promoting women's employment and their right to enjoy educational opportunity and legal status equivalent to that of men. In 1862 the press moved to Farringdon Street, London, where the printing was carried out with steam presses, and in 1867 she handed the management of the press to William Wilfred Head, who bought her out in 1869 and continued to run the press as a vehicle for the employment of women until 1882.