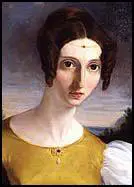

Harriet Taylor

Harriet Taylor, the daughter of Thomas Hardy, a London surgeon, and his wife Harriet Hurst, was born in Walworth, on 8th October, 1807. At the age of eighteen she married John Taylor, a wealthy businessman from Islington. In the next few years Harriet had two sons and one daughter, Helen Taylor.

John and Harriet Taylor both became active in the Unitarian Church and developed radical views on politics. They became friendly with William Johnson Fox, a leading Unitarian minister and early supporter of women's rights.

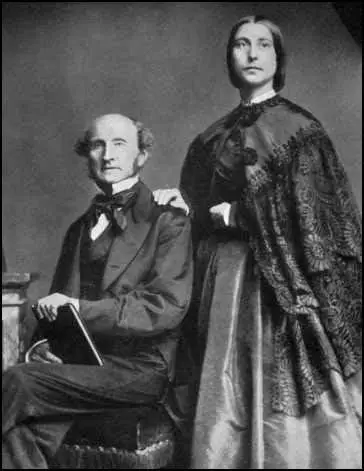

Harriet Taylor moved in radical circles and in 1830 she met the philosopher John Stuart Mill. Taylor was attracted to Mill, the first man she had met who treated her as an intellectual equal. Mill was impressed with Taylor and asked her to read and comment on the latest book he was working on. Over the next few years they exchanged essays on issues such as marriage and women's rights. Those essays that have survived reveal that Taylor held more radical views than Mill on these subjects. She argued: "Public offices being open to them alike, all occupations would be divided between the sexes in their natural arrangements. Fathers would provide for their daughters in the same manner as their sons."

Taylor was attracted to the socialist philosophy that had been promoted by Robert Owen in books such as The Formation of Character (1813) and A New View of Society (1814). In her essays Taylor was especially critical of the degrading effect of women's economic dependence on men. Taylor thought this situation could only be changed by the radical reform of all marriage laws. Although Mill shared Taylor's belief in equal rights, he favoured laws that gave women equality rather than independence.

In 1833 Harriet negotiated a trial separation from her husband. She then spent six weeks with Mill in Paris. On their return Harriet moved to a house at Walton-on-Thames where John Start Mill visited her at weekends. Although Harriet Taylor and Mill claimed they were not having a sexual relationship, their behaviour scandalized their friends. As a result, the couple became socially isolated.

John Roebuck later argued: "My affection for Mill was so warm and so sincere that I was hurt by anything which brought ridicule upon him. I saw, or thought I saw, how mischievous might be this affair, and as we had become in all things like brothers, I determined, most unwisely, to speak to him on the subject. With this resolution I went to the India House next day, and then frankly told him what I thought might result from his connection with Mrs. Taylor. He received my warnings coldly, and after some time I took my leave, little thinking what effect my remonstrances had produced. The next day I again called at the India House. The moment I entered the room I saw that, as far he was concerned, our friendship was at an end. His manner was not merely cold, but repulsive; and I, seeing how matters were, left him. His part of our friendship was rooted out, nay, destroyed, but mine was untouched."

Except for a few articles in the Unitarian journal Monthly Repository, Taylor published little of her own work during her lifetime. However, Taylor read and commented on all the material produced by John Stuart Mill. In his autobiography, Mill claimed that Harriet was the joint author of most of the books and articles that were published under his name. He added, "when two persons have their thoughts and speculations completely in common it is of little consequence in respect of the question of originality, which of them holds the pen."

In 1848 John Stuart Mill's Principles of Political Economy was published. Mill planned to include details of the role that Taylor had played in the production of the book, but when John Taylor heard about this he objected and references to his wife were removed. However, in his autobiography, Mill pointed out thatthe book was "a joint production with my wife".

John Taylor died of cancer on 3rd May, 1849. Still concerned about gossip and scandal, Harriet insisted that they wait two years before they got married. A few months after the wedding the Westminster Review published The Enfranchisement of Women. Although the article had been mainly written by Taylor, it appeared under John Stuart Mill's name. The same happened with the publication of an article in the Morning Chronicle (28th August, 1851) where they advocated new laws to protect women from violent husbands. A letter written by Mill in 1854 suggests that Harriet was reluctant to be described as joint author of Mill's books and articles. "I shall never be satisfied unless you allow our best book, the book which is to come, to have our two names on the title page. It ought to be so with everything I publish, for the better half of it all is yours".

John Stuart Mill had always favoured the secret ballot but Harriet disagreed and eventually changed her husband's views on the subject. Taylor feared that people would vote in their own self-interest rather than for the good of the community. She believed that if people voted in public, the exposure of their selfishness would shame them in voting for the candidate who put forward policies that were in the interests of the majority.

Harriet Taylor and John Stuart Mill both suffered from tuberculosis. While in Avignon, seeking treatment for this condition in November, 1858, Harriet died. Mill and Taylor had been working on a book The Subjection of Women at the time. Helen Taylor, Harriet's daughter, now helped Mill to finish the book. The two worked closely together for the next fifteen years. In his autobiography Mill wrote that "Whoever, either now or hereafter, may think of me and my work I have done, must never forget that it is the product not of one intellect and conscience but of three, the least considerable of whom, and above all the least original, is the one whose name is attached to it."

Primary Sources

(1) Harriet Taylor, unpublished essay on marriage written in 1831.

Marriage is the only contract ever heard of, of which a necessary condition in the contracting parties, was that one should be entirely ignorant of the nature and terms of the contract. For owing to the voting of chastity as the greatest virtue of women, the fact that a woman knew what she undertook would be considered just reason for preventing her undertaking it.

(2) John Roebuck, the Radical M.P. for Bath, was a close friend of John Stuart Mill and pleaded with him to end his relationship with Harriet Taylor. He later recalled what happened when he saw Mill about this matter.

My affection for Mill was so warm and so sincere that I was hurt by anything which brought ridicule upon him. I saw, or thought I saw, how mischievous might be this affair, and as we had become in all things like brothers, I determined, most unwisely, to speak to him on the subject.

With this resolution I went to the India House next day, and then frankly told him what I thought might result from his connection with Mrs. Taylor. He received my warnings coldly, and after some time I took my leave, little thinking what effect my remonstrances had produced.

The next day I again called at the India House. The moment I entered the room I saw that, as far he was concerned, our friendship was at an end. His manner was not merely cold, but repulsive; and I, seeing how matters were, left him. His part of our friendship was rooted out, nay, destroyed, but mine was untouched.

(3) John Stuart Mill, letter to Harriet Taylor (20th March, 1854)

I am but fit to be one wheel in an engine not to be the self moving engine itself - a real majestic intellect, not to say moral nature, like yours, I can only look up and admire.

I shall never be satisfied unless you allow our best book the book which is to come, to have our two names on the title page. It ought to be so with everything I publish, for the better half of it all is yours, but the book which will contain our best thoughts (The Subjection of Women), if it has only one name to it, that should be yours.

(4) In his autobiography published in 1873, John Stuart Mill, gave credit to both Harriet and Helen Taylor for his achievements.

Whoever, either now or hereafter, may think of me and my work I have done, must never forget that it is the product not of one intellect and conscience but of three, the least considerable of whom, and above all the least original, is the one whose name is attached to it."

(5) Harriet Taylor and John Stuart Mill, Westminster Review (1851)

When we ask why the existence of one-half the species should be merely ancillary to that of the other half - why each woman should be a mere appendage to a man, allowed to have no interests of her own that there may be nothing to compete in her mind with his interests and his pleasure; the only reason which can be given is, that men like it.

Custom hardens human beings to any kind of degradation, by deadening the part of their nature which would resist it. And the case of women is, in this respect, even a peculiar one, for no other inferior caste that we have heard of have been taught to regard their degradation as their honour. They are taught to think, that to repel actively even an admitted injustice done to themselves, is somewhat unfeminine, and had better be left to some male friend or protector. It requires unusual moral courage as well as disinterestedness in a woman, to express opinions favourable to women's enfranchisement, until, at least, there is some prospect of obtaining it.

(6) Harriet Taylor, Helen Taylor and John Stuart Mill, The Subjection of Women (1869)

All causes, social and natural, combine to make it unlikely that women should be collectively rebellious to the power of men. They are so far in a position different from all other subject classes, that their masters require something more than actual service. Men do not want solely the obedience of women, they want their sentiments. All men, except the most brutish, desire to have, in the women most nearly connected with them, not a forced slave but a willing one, not a slave merely, but a favourite. They have therefore put everything in practice to enslave their minds. The masters of all other slaves rely, for maintaining obedience, on fear; either fear of themselves, or religious fears. The masters of women wanted more than simple obedience, and they turned the whole force of education to effect their purpose. All women are brought up from the very earliest years in the belief that their ideal of character is the very opposite of that of men; not self-will, and government by self control, but submission, and yielding to the control of others. Men hold women in subjection, by representing to them meekness, submissiveness, and resignation of all individual will into the hands of a man, as an essential part of sexual attractiveness.

(7) Harriet Taylor, Helen Taylor and John Stuart Mill, The Subjection of Women (1869)

The generality of the male sex cannot yet tolerate the idea of living with an equal. Were it not for that, I think that almost everyone, in the existing state of opinion in politics and political economy, would admit the injustice of excluding half the human race from the greater number of lucrative occupations, and from almost all high social functions; ordaining from their birth either that they are not, and cannot by any possibility become, fit for employments which are legally open to the stupidest and basest of the other sex.