Florence Nightingale

Florence Nightingale, the daughter of the wealthy landowner, William Nightingale of Embly Park, Hampshire, was born in Florence, Italy, on 12th May, 1820. Her father was a Unitarian and a Whig who was involved in the anti-slavery movement. As a child, Florence was very close to her father, who, without a son, treated her as his friend and companion. He took responsibility for her education and taught her Greek, Latin, French, German, Italian, history, philosophy and mathematics.

Elizabeth Gaskell described her as "tall, willowy in figure, with thick shortish rich brown hair, a delicate complexion, and grey eyes that are generally pensive but could be the merriest." Her biographer, Colin Matthew, has pointed out: "Florence was a good mimic, attractive to men, and had a number of suitors; many of the men she met through her parents remained lifelong friends.... In spite of these advantages Florence Nightingale was an unhappy young woman. She suffered from bouts of depression and feelings of unworthiness, and she questioned the purpose of life for the upper classes. Unlike her mother and sister, who were content to do good works on the estates, she pondered on the need for charity and the causes of poverty and unemployment."

Religious Conversion

At seventeen she felt herself to be called by God to some unnamed great cause. Florence's mother, Fanny Nightingale, also came from a staunch Unitarian family. Fanny was a domineering woman who was primarily concerned with finding her daughter a good husband. She was therefore upset by Florence's decision to reject Lord Houghton's offer of marriage. Florence refused to marry several suitors, and at the age of twenty-five told her parents she wanted to become a nurse. Her parents were totally opposed to the idea as nursing was associated with working class women.

Florence Nightingale's desire to have a career in medicine was reinforced when she met Elizabeth Blackwell at St. Bartholomew's Hospital in London. Blackwell was the first woman to qualify as a doctor in the United States. Blackwell, who had to overcome considerable prejudice to achieve her ambition, encouraged her to keep trying and in 1851 Florence's father gave her permission to train as a nurse.

Florence Nightingale, now thirty-one, went to Kaiserwerth, Germany where she studied to become a nurse at the Institute of Protestant Deaconesses. Two years later she was appointed resident lady superintendent of a hospital for invalid women in Harley Street, London.

Crimean War

In March, 1853, Russia invaded Turkey. Britain and France, concerned about the growing power of Russia, went to Turkey's aid. This conflict became known as the Crimean War. Soon after British soldiers arrived in Turkey, they began going down with cholera and malaria. Within a few weeks an estimated 8,000 men were suffering from these two diseases.

William Howard Russell, who worked for The Times, reported the Siege of Sevastopol. He found Lord Raglan uncooperative and wrote to his editor, John Thadeus Delane alleging unfairly that "Lord Raglan is utterly incompetent to lead an army". Roger T. Stearn has argued: "Unwelcomed and obstructed by Lord Raglan, senior officers (except de Lacy Evans), and staff, yet neither banned, controlled, nor censored, William Russell made friends with junior officers, and from them and other ranks, and by observation, gained his information. He wore quasi-military clothes and was armed, but did not fight. He was not a great writer but his reports were vivid, dramatic, interesting, and convincing.... His reports identified with the British forces and praised British heroism. He exposed logistic and medical bungling and failure, and the suffering of the troops."

Russell's reports revealled the sufferings of the British Army during the winter of 1854-1855. These accounts upset Queen Victoria who described them as these "infamous attacks against the army which have disgraced our newspapers". Prince Albert, who took a keen interest in military matters, commented that "the pen and ink of one miserable scribbler is despoiling the country." Lord Raglan complained that Russell had revealed military information potentially useful to the enemy.

William Howard Russell reported that British soldiers began going down with cholera and malaria. Within a few weeks an estimated 8,000 men were suffering from these two diseases. When Mary Seacole heard about the cholera epidemic she travelled to London to offer her services to the British Army. There was considerable prejudice against women's involvement in medicine and her offer was rejected. When Russell publicised the fact that a large number of soldiers were dying of cholera there was a public outcry, and the government was forced to change its mind. Florence Nightingale volunteered her services and was eventually given permission to take a group of thirty-eight nurses to Turkey.

Florence Nightingale found the conditions in the army hospital in Scutari appalling. The men were kept in rooms without blankets or decent food. Unwashed, they were still wearing their army uniforms that were "stiff with dirt and gore". In these conditions, it was not surprising that in army hospitals, war wounds only accounted for one death in six. Diseases such as typhus, cholera and dysentery were the main reasons why the death-rate was so high amongst wounded soldiers.

Edward T. Cook, the author of The Life of Florence Nightingale (1913), quoted one of the men in the hospital that she treated: "Florence Nightingale is a ministering angel without any exaggeration in these hospitals, and as her slender form glides quietly along each corridor, every poor fellow's face softens with gratitude at the sight of her. When all the medical officers have retired for the night and silence and darkness have settled down upon those miles of prostrate sick, she may be observed alone, with a little lamp in her hand, making her solitary rounds."

Military officers and doctors objected to Nightingale's views on reforming military hospitals. They interpreted her comments as an attack on their professionalism and she was made to feel unwelcome. Florence Nightingale received very little help from the military until she used her contacts at The Times to report details of the way that the British Army treated its wounded soldiers. John Delane, the editor of newspaper took up her cause, and after a great deal of publicity, Nightingale was given the task of organizing the barracks hospital after the battle of Inkerman and by improving the quality of the sanitation she was able to dramatically reduce the death-rate of her patients.

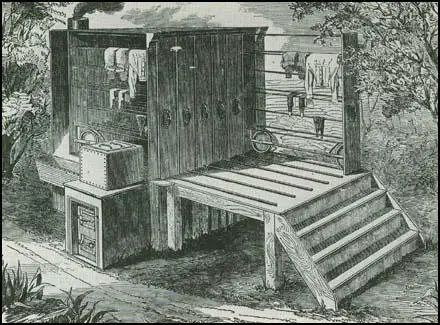

Sidney Herbert wrote "There broke out in different parts of the country a feeling of immediate and spontaneous expression of public gratitude and isolated portions of the country were preparing to make gifts to her." Charles Dickens and Angela Burdett-Coutts were two people who wished to contribute. Nightingale had spoken about the "sodden misery in the hospital". On Dickens's advice, at the end of January 1855, Burdett-Coutts ordered from William Jeakes, an engineer working in Bloomsbury, a drying closet machine. It was built at a cost of £150. It was shipped out in parts and re-assembled in Istanbul. According to The Illustrated London News "1,000 articles of linen can be thoroughly dried in 25 minutes with the aid of Mr Jeakes centrifugal machine which took the wet out of the linen before it is placed in the drying closet." Dr Sutherland, who was working at the army hospital, wrote a letter of thanks to Jeakes: "The wet clothes give in as soon as they have seen it and dry up forthwith. The machine does great credit to Miss Coutt's philanthropy and also your engineering." Dickens commented that the machine was "the only solitary administrative thing, connected with the war that has been a success."

Mary Seacole

Although Mary Seacole was an expert at dealing with cholera, her application to join Florence Nightingale's team was rejected. Mary, who had become a successful business woman in Jamaica, decided to travel to the Crimea at her own expense. She visited Nightingale at her hospital at Scutari but once again Mary's offer of help was refused. Unwilling to accept defeat, Mary Seacole started up a business called the British Hotel, a few miles from the battlefront. Here she sold food and drink to the British soldiers. With the money she earned from her business Mary was able to finance the medical treatment she gave to the soldiers. Whereas Florence Nightingale and her nurses were based in a hospital several miles from the front, Mary Seacole treated her patients on the battlefield. On several occasions she was found treating wounded soldiers from both sides while the battle was still going on.

The war ended in March 1856. Out of 94,000 men sent to the war area, 4,000 died of wounds but 19,000 died of disease, and 13,000 were invalided out of the army. Florence Nightingale returned to England as a national heroine. She had been deeply shocked by the lack of hygiene and elementary care that the men received in the British Army. She later wrote: "I stand at the altar of murdered men and while I live I will fight their cause". Nightingale therefore decided to begin a campaign to improve the quality of of nursing in military hospitals. In October, 1856, she had a long interview with Queen Victoria and Prince Albert and the following year gave evidence to the 1857 Sanitary Commission. This eventually resulted in the formation of the Army Medical College.

Social Reformer

To spread her opinions on reform, Florence Nightingale published two books, Notes on Hospital (1859) and Notes on Nursing (1859). With the support of wealthy friends and John Delane at The Times, Nightingale was able to raise £59,000 to improve the quality of nursing. In 1860, she used this money to found the Nightingale School & Home for Nurses at St. Thomas's Hospital. She also became involved in the training of nurses for employment in the workhouses that had been established as a result of the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act.

Nightingale held strong opinions on women's rights. In her book Suggestions for Thought to Searchers after Religious Truths (1859) she argued strongly for the removal of restrictions that prevented women having careers. Read by John Stuart Mill, it influenced his book on women's rights, The Subjection of Women (1869).

Florence Nightingale was also strongly opposed to the passing of the Contagious Diseases Act. However, Nightingale was unwilling to become involved in the campaign led by Josephine Butler to get this legislation repealed. Nightingale preferred working behind the scenes to get laws changed and disapproved of women making speeches in public. Women such as Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and Sophia Jex-Blake were disappointed by Nightingale's lack of support for women's doctors. Nightingale had doubts at first about the wisdom of this campaign and argued that it was more important to have better trained nurses than women doctors.

Her biographer, Colin Matthew, has pointed out: "At the age of sixty Florence Nightingale considered herself old. Her friends and collaborators were dead, but her health improved. The thin, waspish woman who sent mordant, aphoristic letters to ministers now metamorphosed into a stout, benevolent old lady. She tried to keep up with public-health matters but she was increasingly out of touch.... She continued to write sentimental addresses to probationers until 1889, but by now her eyesight was failing.... She spent almost the whole of her final fifteen years in her room in South Street."

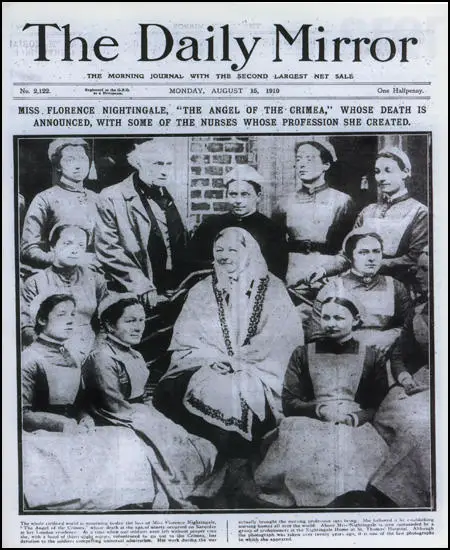

Florence Nightingale died in London on 13th August, 1910.

A copy of this newspaper can be obtained from Historic Newspapers.

Primary Sources

(1) In 1852 Florence Nightingale wrote Cassandra but on the advice of friends she never published the book.

Women are never supposed to have any occupation of sufficient importance not to be interrupted, except "suckling their fools"; and women themselves have accepted this, have written books to support it, and have trained themselves so as to consider whatever they do as not of such value to the world as others, but that they can throw it up at the first "claim of social life". They have accustomed themselves to consider intellectual occupation as a merely selfish amusement, which it is their "duty" to give up for every trifler more selfish than themselves.

Women never have an half-hour in all their lives (except before and after anybody is up in the house) that they can call their own, without fear of offending or of hurting someone. Why do people sit up late, or, more rarely, get up so early? Not because the day is not long enough, but because they have "no time in the day to themselves".

The family? It is too narrow a field for the development of an immortal spirit, be that spirit male or female. The family uses people, not for what they are, not for what they are intended to be, but for what it wants for - its own uses. It thinks of them not as what God has made them, but as the something which it has arranged that they shall be. This system dooms some minds to incurable infancy, others to silent misery.

(2) In her diary Florence Nightingale explained why she decided to turn down the offer of marriage to Richard Moncton Milnes.

I have a moral, an active nature which requires satisfaction and that I would not find in his life. I could be satisfied to spend a life with him in combining our different powers to some great object. I could not satisfy this nature by spending a life with him in making society and arranging domestic things.

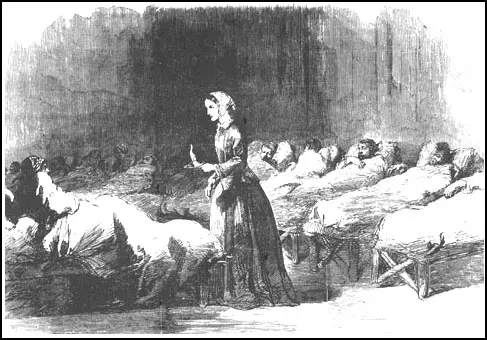

(3) Illustrated London News (24th February, 1855)

Although the public have been presented with several portrait-sketches of the lady who has so generously left this country to attend to the sufferings of the sick and wounded at Constantinople, we have assurance that these pictures are "singularly and painfully unlike". We have, therefore, taken the most direct means of obtaining a sketch of this excellent lady, in the dress she now wears, in one of "the corridors of the sick".

(4) Letter in The Times on the activities of Florence Nightingale at Scutari (February, 1855)

Wherever there is disease in its most dangerous form, and the hand of the spoiler distressingly nigh, there is that incomparable woman sure to be seen; her benignant presence is an influence for good comfort even amid the struggles of expiring nature. She is a 'ministering angel' without any exaggeration in these hospitals, and, as her slender form glides quietly along each corridor, every fellow's face softens with gratitude at the sight of her.

(5) Florence Nightingale, letter to Thomas Longmore on the Geneva Convention (23rd July, 1864)

I need hardly say that I think its views most absurd - just such as would originate in a little state like Geneva, which never can see war. They tend to remove responsibility from Governments. They are practically impracticable. And voluntary effort is desirable, just in so far as it can be incorporated into the military system.

If the present Regulations are not sufficient to provide for the wounded they should be made so. But it would be an error to revert to a voluntary system, or to weaken the military character of the present system by introducing voluntary effort, unless such effort were to become military in its organization.

(6) Henri Dunant, speech on Florence Nightingale at the Geneva Convention (August, 1864)

To the many who pay their homage to Miss Nightingale, though a very humble person of a small country, Switzerland, I yet want to add my tribute of praise and admiration. As the founder of the Red Cross and the originator of the diplomatic Convention of Geneva, I feel emboldened to pay my homage. To Miss Nightingale I give all the honour of this humane Convention. It was her work in the Crimea that inspired me to go to Italy during the war of 1859, to share the horrors of war, to relieve the helplessness of the unfortunate victims of the great struggle on June 24, to soothe the physical and moral distress, and the anguish of so many poor men, who had come from all parts of France and Austria to fall victims to their duty, far from their native country, and to water the poetic land of Italy with their blood.

(7) Florence Nightingale, letter published in the Englishwoman's Review (January, 1869)

I have no peculiar gifts. And I can honestly assure any young lady, if she will but try to walk, she will soon be able to run the "appointed course". But then she must first learn to walk, and so when she runs she must run with patience. (Most people don't even try to walk.) But I would also say to all young ladies who are called to any particular vocation, qualify yourself for it as a man does for his work. Don't think you can undertake it otherwise.

(8) Florence Nightingale, Advice to Nursing Students (1873)

Nursing is most truly said to be a high calling, an honourable calling. But what does the honour lie in? In working hard during your training to learn and to do all things perfectly. The honour does not lie in putting on Nursing like your uniform. Honour lies in loving perfection, consistency, and in working hard for it: in being ready to work patiently: ready to say not "How clever I am!" but "I am not yet worthy; and I will live to deserve to be called a Trained Nurse."

(9) Maev Kennedy, The Guardian (3rd September, 2007)

She is known to generations of children as the saintly, iron-willed Lady With the Lamp who battled to improve the conditions of wounded British soldiers and founded modern nursing, but a strikingly different picture of Florence Nightingale has emerged from the unpublished letters of one of her bitterest enemies.

"Miss Nightingale shows an ambitious struggling after power inimical to the true interests of the medical department," Sir John Hall, the chief British army medical officer in the Crimea, wrote to his superior in London.

When she went over his head to order supplies from his stores, observers, Sir John wrote, were astounded at the "petticoat imperium! in the medical imperio!"

When Nightingale arrived in Scutari in November 1854 with 38 women volunteers, sent by her close friend, the war secretary, Sydney Herbert, she was about to carve out her place in history and destroy Sir John's. Her determination to reform the army hospitals in which thousands of wounded and ill soldiers were treated in closely packed beds by overworked doctors and male medical orderlies, and untrained women whom she dismissed as drunken and slatternly, brought her into instant collision with Sir John - and she also became a media star in the first British war reported in detail by the press.

"It was absolutely as night follows day that her upper-class Victorian female morality would clash head on with his traditional closed male army world," said Richard Aspin, head of the archive and manuscripts at the Wellcome Trust, which recently bought Sir John's letters. "She simply ignored his authority. She would no more have dreamed of consulting him about her nurses than she would have sought the opinion of a husband, if she ever had one, about hiring a parlour maid."

Sir John's letters denounced her as a publicity seeking meddler. Her ambitions, which launched the modern career of nursing, "if not resisted", he wrote, "will, with the influence she has at present at home, throw us completely into the shade in future, as we are at present overlooked in all that is good and beneficial regarding our hospital arrangements, which are ascribed utterly to her presiding genius by great part of the press and her own itinerant eulogistic orators".

He accused her of squandering resources by sacking good nurses and orderlies and trying to take over control of others - "but in that she was disappointed, for they declined to serve under her orders".

It might be some consolation to poor Sir John that the scruffy marbled notebook containing his transcripts of the letters he considered most important cost the Wellcome Trust £4,000, while Nightingale's letters were bought for only £200. One letter from Nightingale, advising on how to find a reliable medical officer for a post in Egypt, warns against employing ex-army doctors: "The fact is, nearly all the half-pay list are blackguards".

Henry Wellcome, who founded the trust, shared the general reverence for the Lady with the Lamp. Hers was the only woman's name he included in the frieze of his library, and he bought the scuffed mocassins she wore at Scutari - now on view in the new museum galleries which opened in London this summer. The collection also owns, but has lent to the British Library, the only known recording of Nightingale's voice, on a wax cylinder.

Hall battled on, writing in February 1856: "The army is in splendid health, only seven deaths in a week and one of them a fit of apoplexy from drunkeness."

However, his view of history's treatment of Nightingale and himself was prophetic. He wrote sadly: "We shall to the end of time be made the victims of public odium in the way we were last winter ... the poor suffering sick soldier is a fine theme to ride off on."

When his long military service was rewarded with a knighthood, Nightingale commented to Sydney Herbert that the honour could only mean "knight of the Crimean burial grounds".[/

(10) Lee Glendinning, The Guardian (3rd September, 2007)

Most biographies of Florence Nightingale attest that she became a national hero after dramatically reducing the mortality rate at the Scutari hospital during the Crimean war. But new research casts doubt on her role in transforming the hospital after her arrival in 1854. Official records show that by February 1855, the mortality rate had fallen from 60% to 42.7% and then, once a fresh water supply was introduced, it dropped further to 2.2%.

Recently historians have suggested the death rate among soldiers did not fall immediately but rose, and was higher than any other hospital in the region. During Nightingale's first winter there, 4,077 soldiers died, mostly of typhus, typhoid, cholera and dysentery. Ten times more died of these illnesses than from battle wounds.

The death rate began to fall six months after she took charge - only after a sanitary commission was sent out by Lord Palmerston to improve ventilation and clean out the sewers.

Nightingale had believed the mortality rates were due to poor nutrition and overworking of soldiers. But Hugh Small, author of Florence Nightingale: Avenging Angel, claims an unpublished letter shows it was not until 1857 that she realised the conditions within the hospitals themselves had caused such a huge number of deaths.