Time and Tide

Margaret Haig Thomas, Lady Rhondda, decided to use some of her wealth to publish the feminist political magazine Time and Tide. The first edition was published on 14th May 1920: "Women have newly come into the larger world, and are indeed themselves to some extent answerable for that loosening of party and sectarian ties which is so marked a feature of the present day. It is therefore natural that just now many of them should tend to be especially conscious of the need for an independent press, owing allegiance to no sect or party. The war was responsible for breaking down the barriers which kept each individual or group of individuals in a watertight compartment. The past five years have taught the importance of that wider view which sees the part in relation to the whole. There is another need in our press of which the average person of today is conscious, but which must specially weigh with women - the lack of a paper which shall treat men and women as equally part of the great human family, working side by side ultimately for the same great objects by ways equally valuable, equally interesting; a paper which is in fact concerned neither specially with men nor specially with women, but with human beings." (1)

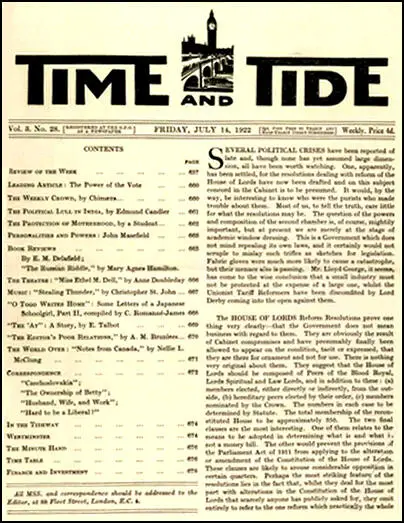

Its masthead included a drawing of the tidal River Thames below the House of Parliament and Big Ben. This signified the magazine's interest in Westminster politics. Margaret wanted it to have a similar impact to the New Statesman. She hoped it would "mould the opinion" not of the masses but of what she called "the keystone people", the vanguard who in turn would influence and guide the many. (2)

According to Deirdre Beddoe: "Time and Tide was for Lady Rhondda the fulfilment of a childhood dream. It was her grand passion, to which she devoted all her energies, at the expense of her business interests and her health. Though it was nominally owned by a limited company (the Time and Tide Publishing Company) and incorporated with £20,000 capital, Lady Rhondda subsidized the journal from the outset. She controlled 90 per cent of the shares, was at first vice-chairman, then chairman of directors." (3)

Lady Rhondda believed that the major problem that women faced was the scale of the prejudice which fuelled the opposition to attempted reforms. She maintained that after the war the women's movement was engaged in two battles, to achieve legislative progress for women and to change public opinion. (4)

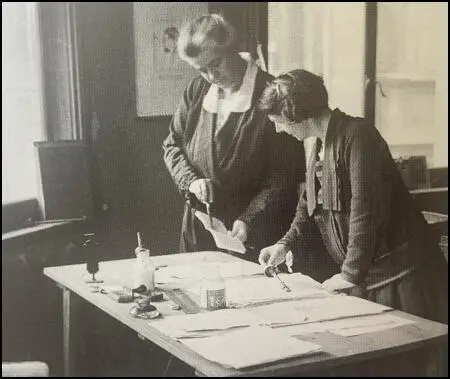

Time and Tide was edited by Margaret's lover, Helen Archdale who had been a fellow member of the Women's Social & Political Union who had spent two months in Holloway after participating in the mass window-breaking in 1911. After becoming the WSPU prisoners' secretary and worked on The Suffragette where she gained compositing and editing skills that helped her in her new job. (5)

Helen Archdale (on the left) at the Time offices (c. 1922)

Time and Tide argued throughout the 1920s that it was a mistake for women to join parties while they remained so low down the political agenda. "Instead women should somehow band together as voters and force the parties to change their priorities... As the 1920s wore on it was increasingly reduced to criticising the parties for failing to place women in winnable seats and women politicians for giving excessive loyalty to their male leaders." (6)

However, she did praise the Labour Party for creating women's sections. In doing so it attracted 100,000 women members. (7) Barbara Ayrton Gould wrote: It is large; it is going to become larger; and it is new. Consider the importance of that. Men voters are still bound fast in the hoary and Tory traditions of the old-established Parties... Women... simply because they are newcomers to politics are free from this constraint." (8)

Margaret Haig Thomas, Lady Rhondda, believed that "it is the strength of the non-party women's organisations rather than the number of women attached to the party organisations which is likely to decide the amount of interest taken by the parties in women's questions." (9)

Although the journal could be described as a success, it never developed into a major weapon for feminism. Lady Rhondda's critics complained that she developed an elitist strategy. At a time when 8 million women had recently obtained the vote, she showed no sign of wanting it to be read by a wide public. She later wrote she intended it to be a "first-class review" that was "read by comparatively few people, but they are the people who count, the people of influence". (10)

Lady Rhondda did not allow politics to get in the way of good writing and contributors to the magazine included D. H. Lawrence, Rebecca West, Vera Brittain, Winifred Holtby, Virginia Woolf, Crystal Eastman, Charlotte Haldane, Storm Jameson, Nancy Astor, Margaret Bondfield, Margery Corbett-Ashby, Charlotte Despard, Emmeline Pankhurst, Eleanor Rathbone, Olive Schreiner, Helena Swanwick, Margaret Winteringham, Ellen Wilkinson, Ethel Smyth, Emma Goldman, George Bernard Shaw, Ernst Toller, Robert Graves and George Orwell. However, it never sold well and it is estimated that during the thirty-eight years she lost over £500,000 on the magazine. The last edition of the magazine was published on 15th February 1958. (11)

Primary Sources

(1) Margaret Rhondda, Time and Tide (14th May, 1920)

That the group behind this paper is composed entirely of women has already been frequently commented on. It would be possible to lay too much stress upon the fact. The binding link between these people is not primarily their common sex. On the other hand, this fact is not, without its significance. Amongst those to whom the need we have spoken of is apparent today are a very large number of women. Women have newly come into the larger world, and are indeed themselves to some extent answerable for that loosening of party and sectarian ties which is so marked a feature of the present day. It is therefore natural that just now many of them should tend to be especially conscious of the need for an independent press, owing allegiance to no sect or party. The war was responsible for breaking down the barriers which kept each individual or group of individuals in a watertight compartment. The past five years have taught the importance of that wider view which sees the part in relation to the whole.

There is another need in our press of which the average person of today is conscious, but which must specially weigh with women - the lack of a paper which shall treat men and women as equally part of the great human family, working side by side ultimately for the same great objects by ways equally valuable, equally interesting; a paper which is in fact concerned neither specially with men nor specially with women, but with human beings. It must be admitted that the press of today, although with self-conscious, painstaking care it now inserts "and women" every time it chances to use the word "men" scarcely succeeds in attaining to such an ideal.

(2) Rebecca West, reviewed Jailed for Freedom by Doris Stevens in Time and Tide on 24th March, 1922.

They (members of the Congressional Union for Women Suffrage) found that the police while constantly arresting them for minute technical offences, would not interfere when they were assaulted by hooligans, and later on led Government-organised crowds of uniformed soldiers and sailors against them. They went to prison and, in an interesting penal institution called the Occoguan workhouse, were fed on worm-crawling food and exposed in insanitary conditions and when they denounced this state of affairs, not only on their own account but (as has always been the gentlemanly suffragist way), on behalf of the ordinary offenders, the administration called to mind a penitentiary in a swamp, which had been declared unfit for human habitation nine years before, and put them there. All this they endured and thereby, without any doubt at all, acquired the vote. With extraordinary naivety the United States Government failed to cover up its tracks and left it patent that it gave women the franchise not because of any consideration of justice, but because they were a nuisance. There was no such magnificent exhibition of the art of climbing down in the grand manner (with classical quotation from Mr. Asquith) as our Parliamentary debate on the passing of the Act. A crude, new country America; but no doubt it will learn.

(3) Editorial, Time and Tide (23rd May, 1922)

On December 23rd, 1919, the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act passed into law, and for the past two years or more it has been gradually dawning upon women of all classes, ages and professions, that the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act does not remove sex disqualification.

Let us examine this Act a little more closely. When it was passed it was presented by the Government as a Charter of Freedom. Henceforth women were to enjoy equal opportunities, equal chances, equal rights with men. It was a reversal of the customs of the ages. It was, as Mr. Talbot pointed out last Friday, a revolutionary piece of legislation. Incidentally it was the carrying out of a pledge made by the Coalition to the women just before the previous General Election and signed by Mr. Lloyd George and Mr. Bonar Law: 'It will be the duty of the new government to remove all existing inequalities in the law as between men and women.'

Specifically, of course, the Act did not do a very great deal. It was quite short, consisting of four clauses only. The first clause dealt with the admission of women to the Civil Service, to which, for practical purposes, if not in theory, they had been admitted before; and to juries, which was a new departure. It also entitled women to become magistrates and to be admitted and enrolled as barristers or solicitors. The first sub-clause to clause I contracted out of the obligations of the Act to admit women on equal terms into the Civil Service by providing that all regulations dealing with this admission should be left to Orders in Council.

The second sub-clause to clause I gave power to a judge to order that a jury should be composed of men only or women only as the case might be, and that on application being made a woman might be exempted from serving in a case 'by nature of the evidence to be given or of the issues to be tried.'

The second clause dealt with the qualifications necessary to entitle women to be admitted and enrolled as solicitors on the same terms as men.

The third clause stated that nothing in the statutes or charter of any university should be deemed to preclude the authorities of such university from admitting women to its membership. It was as a result of this that in 1920 Oxford admitted women to full membership. The clause was, however, merely permissive, and Cambridge has elected not to act upon it. Women were already admitted to membership of every other university in the United Kingdom before this date.

The fourth clause was simply the short title and repeal clause usual in Acts of Parliament.

To sum up, what the Bill actually did was:- To admit women to jury service although not on the same terms as men. To allow women to become magistrates. To allow women to become barristers or solicitors. To grant power to Oxford and Cambridge to admit women to membership if they chose.

(4) Editorial, Time and Tide (17th October, 1922)

It is true that we have been most singularly fortunate in our first two women members. They have set a standard to which few could hope to attain. Nevertheless, even though we can scarcely hope that many future women M.P.'s will achieve so conspicuous a success as have the first two it is undoubtedly most desirable to add to their number. In the last Parliament Lady Astor and Mrs. Wintringham were doing the work often ordinary people. No human being can be expected to keep going indefinitely at such a pressure. We publish today the first of a series of three articles dealing in some detail with the chances of the prospective women candidates who have been adopted up to the present. It seems clear from a close scrutiny of the list of seats placed at their disposals that none of the Parties have been prepared to pay much more than lip service to the proposition that it is desirable to have women in Parliament. The Independent Liberals head the list so far as numbers are concerned, but even the Independent Liberals do not so far appear to have given their women candidates any safe seats. Perhaps, however, there was some excuse for the 'Wee Frees,' seeing that they had not many safe seats to give.

Few people who have closely followed the course of events in the last Parliament will be found to deny that there is need in the next for a greater representation of women. And this not only on the general grounds that it is desirable to have national political problems fully envisaged from every possible angle, but also and at the present time particularly because there are still today a certain number of subjects the importance of which tends to be underrated by many of the men in Parliament but is adequately appreciated by women. The value of Lady Astor and Mrs. Wintringham has lain not only in their contributions upon general political questions but also in the steady hard work they have put in over such matters as the Criminal Law Amendment Bill (whose passage was largely due to their efforts), the Equal Guardianship of Infants Bill, the Women Police question (that any Women Police at all have been retained in the London area is due almost entirely to them), and other matters of the kind. It has lain also in the fact that they could be trusted to understand the point of view of the professional and working woman.

(5) Editorial, Time and Tide (19th January, 1922)

Mr. Fisher continues to advise teachers in The Teachers' World. Last week he discoursed upon 'Equal Pay.' He was disturbed lest any one should suppose that he thought it the duty of the teacher to be occupied with political or financial questions. 'The best teachers,' he explained, 'have better things to think about than salaries or trades union policy. They do not care about the politics of the profession. They are in fact the salt of the earth.' Unfortunately, the best grocers and butchers still continue to take an active interest in prices. Mr. Fisher however has - a soul above such mundane considerations. He is entirely opposed to equal pay; he admits that 'the demand has an obvious foundation in reason. The women teachers are as well qualified as the men, and they work as long hours,' but he declares that 'while it is on public grounds desirable that the male teacher in our elementary school should marry early, it is desirable that the female teacher should for some years remain unmarried' (a statement which by itself is worth some consideration), and he appears to have some hazy notion that paying a woman less will somehow prevent her marrying; although why it should do so in a profession which in any case almost always dismisses her when she does marry is not very easy to see. In any case, Mr. Fisher is perfectly clear as to his practical views on equal pay. To bring the women's pay up to the men's would cost, so he tells us seven millions, and at present he does not think we have the money to spend. But if we had (and he does not press for fresh money) he would not dream of spending it on removing this admitted injustice - no, he would 'spend it on the children.' He has not the imagination to realise that to allow the majority of the teachers to suffer from a rankling sense of injustice is exceedingly bad for the children.

(6) Rebecca West, Time and Tide (9th February, 1923)

The real reason why women teachers are paid less highly than men who are performing the same work is the desire felt by the mass of men that women in general should be subjected to every possible disadvantage. Men like women in particular; for their wives, their sweethearts, their mothers, and their sisters they can feel as generous and self-sacrificing love as the world knows. But all save the few who have cut down the primitive jungle in their souls want women in general to be handicapped as heavily as possible in every conceivable way. They want this not out of malignity, but out of a craving to be reassured concerning themselves and the part they are playing in the difficult universe. They fear they are not doing well enough. (That fear, enchantingly humble, should keep us forever from bitterness against them. For they do marvellously well.) It would help them to have faith in themselves if they could see others doing much worse. So, hiding their purpose from themselves by a screen of argument they set about contriving that women shall furnish them with this welcome sight. If we are honest and not tainted with the modern timidity about mentioning that there is such a thing as sex-antagonism we must admit that they do this in various unpleasing ways. They exclude her from as many occupations as possible on the ground that she is incapable of following them, thus providing the double benefit of filling the male practitioners of those occupations with a proud sense that they are doing something which half the world cannot, and of embarrassing the woman worker by restricting the market for her labour. They debase the specific work of women as wives and mothers by urging that they should undertake it because they are too weak and foolish to succeed in any other. And wherever possible they arrange that women shall face life in that unequipped condition which comes of having too little money. A person insufficiently fed and clothed is apt to be most satisfyingly inferior to a person who is sufficiently fed and clothed. It is this savage form of sex-antagonism which makes people desire that women teachers should be paid less highly than men who are performing the same work. Since there are so many women engaged in the profession of teaching, and the payment of men teachers is none too high, this affords a pleasing prospect of female discomfort and inferiority on a large scale.

(7) Crystal Eastman, Time and Tide (20th July, 1923)

History has known dedicated souls from the beginning, men and women whose every waking moment is devoted to an impersonal end, leaders of a "cause" who are ready at any moment quite simply to die for it. But is it rare to find in one human being this passion for service and sacrifice combined first with the shrewd calculating mind of a born political leader, and second with the ruthless driving force, sure judgment and phenomenal grasp of detail that characterize a great entrepreneur.

It is no exaggeration to say that these qualities are united in Alice Paul, the woman who inspired, organized and led to victory the militant suffrage movement in America and is now head of the Woman's Parry, a strong group of conscious feminists who have set out to end the "subjection of women" in all its forms.

Alice Paul comes of Quaker stock and there is in her bearing that powerful serenity so characteristic of the successful Quaker. Like many another famous general she is well under five foot six, a slender, dark woman with a pale, often haggard face, and great earnest childlike eyes that seem to seize you and hold you to her purpose despite your own desires and intentions. During that seven year suffrage campaign she worked so continuously, ate so little and slept

so little that she always seemed to be wasting away before our eyes. Once in the early years, when the Union was housed in a basement impossible to ventilate she seemed so near to collapse that she was taken, under protest, to a nearby hospital to rest. But she had a telephone put in by her bed, and went right on with the campaign, forgetting, as usual, to eat and sleep. After a few weeks of this she got up and packed her bag and came back to the foul air and artificial light of that crowded basement headquarters. And nothing more was said about a breakdown. The truth is, of course, that she looks frail, as anyone would who was subjected to constant overwork and under- nourishment, but actually she possesses a bodily constitution of extraordinary strength, and a power of physical endurance that quite matches her indomitable spirit.

(8) Editorial, Time and Tide (16th November, 1922)

Up to the time of going to press only sixteen women parliamentary candidates have been officially endorsed by their respective parties. It seems certain that more women candidates will be adopted almost immediately, but in most cases these will only be asked to fight forlorn hopes. We much doubt the desirability of women candidates accepting the party leavings. In fact, what the parties are doing is to fling to any women who are prepared to accept them - and in most cases to pay the greater part of their own expenses - constituencies which the average male candidate refuses to touch knowing them to be 'duds.' When the women get defeated, as in these hopeless seats they can only expect to be, the parties who have thus used them are the first to turn round and say: 'There is no use putting up women candidates, they only get defeated.' We are of opinion that women of any standing should refuse to be made use of in this way, their defeat only does harm to the ultimate cause they desire to serve. It should be remembered that there is no generosity in offering a woman the chance of fighting a hopeless seat on condition that she pays her own expenses. The party which does so is merely trying to get something for nothing by playing on the comparative innocence of women in the political game.

(9) Elizabeth Robins, Time and Tide (16th November, 1922)

The Six Points:

1. Satisfactory legislation on child assault.

2. Satisfactory legislation for the widowed mother.

3. Satisfactory legislation for the unmarried mother and her child.

4. Equal guardianship.

5. Equality of pay for men and women teachers.

6. Equality of pay and opportunity for men and women in the Civil Service.

The Six Point Group is young but it has already a history of considerable importance.

The first page was written on February 17,1921, when a little group of women framed a programme of social betterment which should appeal in two ways to people of practical mind. (1) It offered a non-party rallying ground for much previous dispersed (and therefore less effectual) effort. (2) It was a political instrument to hasten the ends desired, by the only sure means, i.e., the Government measure.

In order to fulfil the preliminary qualifications it was necessary to confine the programme to questions which by their easily understood urgency should invite general response, and by their fundamental character should enlist the support of organised bodies.

This last essential was achieved by the foresight of the framers. They had chosen out of all the reforms necessary to put men and women on an equal footing, politically and economically, those measures on which public opinion is most ripe for legislation.

This was proved (1) by instantaneous success in adding individual names to the group membership. (2) By the steadily growing number of societies desiring to co-operate with the group.

In a list of twenty-four, occurs: The British Federation of University Women, the Federation of Women Civil Servants, and the National Union of Women Teachers, along with Co-operative Guilds, Women Citizens' Associations, and others.

On August 26,1921, the Six Point Group was affiliated to the Consultative Committee which meets under the chairmanship of Lady Astor.

(10) Editorial, Time and Tide (25th January, 1924)

For many years past Labour has definitely declared its belief in complete equality between the sexes: it is therefore not surprising that many nonparty women are welcoming with enthusiasm the advent of the first Labour Government, in the expectation that all their legal disabilities will now be finally abolished. There can be little doubt that if Labour does pass the legislation necessary to place both sexes on an equal footing before the law, in their public as well as their private capacities, and succeeds in showing no sex prejudice in administrative work, it will gain such confidence with the nonparty women's organisations that the other parties will find difficulty and perhaps impossibility in displacing it from their favour for a number of years to come. At this juncture, therefore, it may be worth the new Government's while to inquire as to what exactly the nonparty women's organisations are demanding.

There is no difficulty in discovering what these organisations regard as the immediate instalment of their programme and are demanding to have done this session. This has been made abundantly clear within the past few weeks by all the leading societies. In December the Consultative Committee of Women's Organisations passed resolutions, which had been moved by the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship, asking whichever of the parties might be returned to power for three things: (1) The granting of the franchise to women on the same terms as men; (2) Equal rights and responsibilities over their children for mothers and fathers; (3) Pensions for civilian widows with dependent children. These resolutions were endorsed by nineteen constituent societies, including such important bodies as the National Council of Women, the Federation of Women Civil Servants and the Association of Women Clerks and Secretaries.

This week, on the advent to power of the new Ministry, the Six Point Group passed a resolution calling upon the Labour Government this session 'to rectify the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act, to pass a measure giving pensions to widows with dependent children, and to pass a measure giving equal rights of guardianship to married parents'; whilst at their Annual Conference, just concluded, the National Union of Women Teachers declared that what was needed was a Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act which 'meant what it said and said what it meant.' Lastly, the Women's Freedom League is holding a Public Meeting on February 6th (the sixth anniversary of the passing into law of the Representation of the People Bill, which gave the vote to the majority of women over thirty), with the object of pressing for the immediate extension of the vote to women 'at the same age and on the same terms as men have it.'

In view of these declarations, no Ministry can mistake the demands of the women's organisations. The immediate programme upon which they are set is perfectly clear:-

(1) Pensions for fatherless children.

(2) Equal guardianship.

(3) Equal franchise.

(4) The rectification of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act.

Nor are the omens unpropitious. In the course of the statesmanlike speech in which he moved the vote of want of confidence last Friday, Mr. Clynes - now leader of the House of Commons - found time to regret that the King's Speech did not include 'proposals for passing into law a measure to provide pensions for widowed mothers'; whilst the Manifesto issued by the Labour Party at the last election stated: 'Labour stands for equality between men and women: equal political and legal rights, equal rights and privileges in parenthood, equal pay for equal work.' In order to attain these things the removal of sex disqualification, the granting of the franchise on equal terms to men and women and an equal guardianship measure, are obviously the first steps.

(11) Winifred Holtby, Time and Tide (6th August, 1926)

Hitherto, society has drawn one prime division between two sections of people, the line of sex-differentiation, with men above and women below. The Old Feminists believe that the conception of this line, and the attempt to preserve it by political and economic laws and social traditions not only checks the development of the woman's personality, but prevents her from making that contribution to the common good which is the privilege and the obligation of every human being.

While the inequality exists, while injustice is done and opportunities denied to the great majority of women, I shall have to be a feminist, and an Old Feminist, with the motto Equality First. And I shan't be happy till I get it.

(12) Helena Swanwick, Time and Tide (4th November 1927)

The earlier struggles of women for emancipation necessarily take the form of beating at the closed doors of life. Till these are opened and we can see for ourselves what there is of knowledge and opportunity we cannot know how much we can put to good use. Many of these doors are still closed, but far more have been opened even in my lifetime than, as a girl, I should have ventured to hope. Our immediate and difficult task is to test all and reject what is not for us; to modify much and adapt it to our needs and natures. It is a commonplace to say that women are born into a world still largely man-made, it is their business to modify it till it becomes a human world as fit for full-sized women to live in as for full-sized men. It is my conviction that most men have not a notion how immensely better the world could be made for them, by the full co-operation of women. But that's another story.

The welfare and the wealth of a society depend upon the full functioning of all the beneficent and productive activities of all its members. The health and happiness, the mental growth and development of all these members depend upon their full functioning. Therefore all theories of the State, or of government, or of family organization which require the limitation or restriction of such functioning are sterilizing theories; all conditions of society which make such limitation or restriction inevitable, are diseased conditions and intelligent people will not sit down content with the disease and its resultant restrictions, but will set about removing the disease and the restrictions with it. Sometimes the removal of the restrictions actually precedes and encourages the removal of the disease.

(13) Helena Swanwick, Time and Tide (11th November 1927)

It takes a very patient and understanding sort of woman not to go off the deep end when she hears men talk of 'the unfair competition of women.' Because women carry a pretty heavy handicap; because the conditions of their lives in the past have made their organisation very difficult and they have therefore been more docile in the hands of employers; because their work is apt to be more intermittent (owing to domestic claims) and more unskilled (owing to lack of training); because they have schooled themselves, through necessity, to wait on themselves and spend less on themselves than their male fellow-workers do these fellow-workers complain of their 'unfair competition' and have made persistent efforts, which are by no means ended to exclude women from any work which is attractive enough for men to desire it. This is the real sex war and, like all war it is immensely wasteful of life, it creates an immense amount of ill-feeling and it does not arrive at the desired results.

Women must work because they need the work and the independence resulting from it and because the community needs it. Women should have the same reasonable freedom in the choice of their work as men have. And it is no answer to this plea to say (as one often hears said) that men have very little choice; for their condition is not bettered by worsening that of women and they would do well to join forces with women in improving the education and organization of all human beings of both sexes so that they might all be better adapted to the work they undertake. One most vital reform is to keep children out of the labour market.

(14) Helena Swanwick, Time and Tide (18th November 1927)

The old theory is that a man 'keeps' his wife, and this is just, so long as he prevents her from keeping herself. But when a woman becomes able to keep herself, and when the conditions of marriage allow of her exercising this ability, there will be no moral basis for the claim that a man should 'keep' his wife. It is a claim deeply demoralising to both parties. He may employ her, and pay her; she may employ him, and pay him; they may go into partnership together. But a self-respecting girl does not like the notion of being 'kept.' Marriage in itself is not work, and should not be paid for. It is no longer universally held to be a wife's duty (any more than a daughter's duty) 'to be there,' always on tap as it were. This, in itself, is a great improvement in the married state, bringing that element of variety and independence which prevents satiety and the devastating habit of taking everything for granted. Doubtless it will often be convenient, so long as individual-run homes exist, for the wife to do, or to supervise, the domestic work. If she does this efficiently she should be paid the value of it; in the case of inefficiency the work and the pay should be transferred to another. The conditions of these individual homes are becoming increasingly distasteful to women, many of whom seem to have no aptitude at all for domestic work, and dislike the confinement and solitude. For these women some form of cooperative housekeeping is the obvious solution; incidentally also this is a far more economical way of carrying on domestic business. A considerable part of this cooperative housekeeping will naturally be done by men as cooks, furnace-men, cleaners, etc., for men's gregariousness at once leads them to take up women's work (for example, a spinster's) when they can do it in company, and be paid for it.