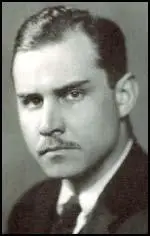

Briton Hadden

Briton Hadden, the son of Crowell Hadden Jr. and Bess Busch, was born in Brooklyn Heights, on 18th February, 1898. His grandfather, Crowell Hadden, was the head of the Brooklyn Savings Bank. Briton's father had been married to Bess's sister, Maud, who died giving birth to Crowell Hadden III. In 1900 Bess had a second child, who was named after her dead sister.

From early childhood, Hadden showed a love for language. He also had a photographic memory and by the age of four he was happily memorizing the poems of John Greenleaf Whittier. The following year he began writing his own poems.

In 1905, when Hadden was seven, his father caught typhoid fever and died. Isaiah Wilner, the author of The Man Time Forgot (2006), has argued: "Hadden's mother, having lived through the deaths of both her sister and her husband, sank into a period of fatigue, anxiety, and depression, and was often directed by her doctors to take the rest cures in the country. Bess Hadden was a buoyant soul, however, and her condition improved. Eventually, she would marry Dr. William Pool, an obstetrician who lived a few blocks away."

Hadden continued to write and as a student at the Brooklyn Poly School he started his first publication, the Daily Glonk. It tended to make fun of his teachers and fellow students. As his biographer points out, "Hadden's tendency to poke fun in public fun at public figures previously accustomed to respectful treatment would become a key aspect of his writing style."

Hadden also became interested in politics. Like the rest of the family he supported the Republican Party. However, one of his friends favoured the Democratic Party. They had heated arguments. He told his mother that when he was older "I'm going to put out a magazine.... when I grow up which will tell the truth. Then there won't be all this confusion about who's right." He said the magazine would be small so that it could be placed in a pocket but large enough to hold the essential facts.

In 1913 Hadden was sent to Hotchkiss School in Connecticut, where he met Henry Luce, another young man who was very interested in becoming a journalist. Soon after arriving the Hotchkiss Record, announced a new competition for sophomores. The student who showed the most "natural ability" would be taken onto the board of the newspaper. Hadden came first, beating Luce into second place. Luce wrote to his father: "I am second though quite far behind the first fellow (Hadden) and while I am not satisfied with second place, yet I think it was worthwhile."

In his senior year, Hadden became editor of the Hotchkiss Record. Luce now decided to concentrate on the Hotchkiss Literary Monthly. A fellow worker on the magazine Culbreth Sudler, later recalled: "He (Luce) had a kind of terrifying egotism. Everything was up there in his head. His personality, his manner, didn't matter. Nothing mattered except the idea."

Hadden made several changes to the student newspaper. Isaiah Wilner has pointed out: "Hadden concocted a plan to print the Hotchkiss Record twice a week instead of once, a schedule that would bring in twice the advertising revenue and give the paper a better chance of breaking news. Hadden also moved the editorials page from the middle of the paper to the second page and eradicated the practice of reprinting editorials from college papers... At the start of his senior year in the fall of 1915, Hadden released a dramatically changed issue of the Hotchkiss Record. The newspaper was curt, factual, and fun to read, and in his first editorial Hadden did not mince words." Hadden claimed he would print "the facts as we see them in an absolutely unbiased and impartial manner."

In November 1915 Hadden began to print his own weekly world news summary down the left side of the front page. At the top of the first column, he told his readers that it was his lifelong goal to explain "the important happenings of the week to those of us who do not find time to read the detailed accounts in the daily papers." This often included accounts of the First World War. In March 1916 he wrote about the German attack on Verdun: "That they renew massed attacks undererred by carnage, speaks well for discipline, but it is the work of automatons, not men."

Hadden and Henry Luce both went to Yale University and found themselves in competition to have their work published in the Yale Daily News. This involved what was known as "heeling rituals". Between October and March, the young students (heelers) wrote articles, sold advertising in the newspaper and performed various tasks for the editorial board. The editors awarded a certain number of points for each task. At the end of the competition, the top four heelers were appointed to the staff of the newspaper. Alger Shelden, the son of a millionaire attempted to buy his way to victor. However, he could only finish second to Hadden, who won with more points than any heeler in history. Luce finished in fourth place. Luce wrote to his father: "I have come to Rome and succeeded in the Roman Games."

Shelden invited Hadden, Luce and the fourth successful heeler, Thayer Hobson, to spend Easter at the family estate at Grosse Pointe near Detroit. Hadden wrote to his mother that he had accepted the invitation because he wanted to become better acquainted with Shelden, Hobson and Luce "whom I will have to work with more or less during the next few years". Luce told his father that he was excited by the visit as Shelden's father was a close friend of Theodore Roosevelt. While they were staying at the Shelden estate, President Woodrow Wilson declared war on Germany.

When they arrived back at Yale University Hadden and Luce launched a campaign in the Yale Daily News to support the war effort by encouraging the wealthy students to purchase war bonds. They also encouraged young men to join the armed forces and by the autumn of 1917 a third of the students at Yale had left to take part in the First World War. This included John Elliot Wooley, the chairman of the newspaper. Luce and Hadden both put their name forward for the top job. Hadden was elected to the post and Luce wrote to his parents: "Briton Hadden is chairman of the News, and thus my fondest college ambition is unachieved."

Hadden used his new position to call for Yale to offer more classes in subjects like semaphore signaling and drill. This campaign was successful and according to one observer, "for the rest of the war the school became a military academy in all but name". Luce was also a strong supporter of the war effort. He accused his English professor of being a pacifist and suggested that Yale should ban all student groups that could not be classified as "war industries". Hadden and Luce would often print fake letters in order to create debates about controversial subjects. This strategy increased sales of the newspaper.

The following year Hadden was elected chairman of the Yale Daily News for a second time and Luce won election as the managing director. During this period the two young men became very close. Luce later commented: "Somehow, despite greatest differences in temperaments and even in interests, somehow we had to work together. At that point everything we had belonged to each other."

Hadden's written style was deeply influenced by his English professor, John Milton Berdan. In his classes he encouraged his students to communicate to a mass audience. Hadden remembers him saying: "Your job is to write for them all." He argued that the most important thing for a writer was to observe the world, "to see for oneself". Berden added that you kept the reader's attention by communicating with "brevity, clarity and wit".

Luce and Hadden both wanted to become members of the Skull and Bones group. Only fifteen students were allowed to join each year. They achieved the honour in 1919. Other members of this secret society include William Howard Taft, Henry L. Stimson, William Averell Harriman, Clarence Douglas Dillon, James Jesus Angleton, William F. Buckley, Frederick Trubee Davison, McGeorge Bundy, Robert A. Lovett, Potter Stewart, Lewis Lapham, George H. W. Bush and his son, George W. Bush.

After graduating, Hadden went to New York City in an attempt to find a newspaper job. He greatly admired the work of Herbert Bayard Swope, the editor of the New York World. Hadden marched into Swope's office unanounced. Swope yelled: "Who are you." He replied: "My name is Briton Hadden, and I want a job." When the editor told him to get out, Hadden commented: "Mr. Swope, you're interfering with my destiny." Intrigued, Swope asked Hadden what his destiny entailed. He then gave him a detailed account of his plans to publish a news magazine but first he felt he had to learn his craft under Swope. Impressed by his answer, Swope gave him a job on his newspaper.

Hadden's reports soon became appearing on the front page. Swope liked Hadden's conservational style of writing and began giving him the top stories to cover. One of his fellow reporters suggested that Hadden had an "intelligent brain, with baby thoughts". Swope also invited him to his house for dinner and became attending his legendry parties, where he met the writer, F. Scott Fitzgerald, who later used these experiences for his masterpiece, The Great Gatsby (1925).

Hadden told Frederick Darius Benham, who worked with him on the New York World, about his plans to publish a news magazine. Hadden once showed Benham a copy of the New York Times: "See this? Full of wonderful news, tells you everything going on in the world. But you haven't got time to read it all every day... I have got an idea to start a magazine which comes out on Friday with all the news condensed so you and all the other people commuting home for the weekend can catch up on the news they missed."

In 1921 Hadden, on the recommendation of his friend, Walter Millis, got a job with the The Baltimore News-Post. The editor was pleased with Hadden's work and asked him if he had any friends who could write like him. Henry Luce had just been sacked from the Chicago Daily News and Hadden suggested his name and he took up the post in November.

They spent much of their spare-time discussing the possibility of starting their own news magazine. Hadden argued that most people in the United States were fairly ignorant of what was going on in the world. According to Hadden, the main problem was not a lack of information, but too much. He pointed out there were over 2,000 daily newspapers, 159 magazines and nearly 500 radio stations in America. The two men objected to the emphasis placed on entertainment by these various media organisations. The situation became worse when in 1919 a Chicago publisher, Joseph Medill Patterson, moved to New York City and launched his tabloid newspaper, the Daily News. Making good use of photographs, the newspaper concentrated on murder stories and celebrity scandals.

Luce and Hadden intended to change this trend by producing a magazine that dealt with serious news. Luce wrote to his father: "True, we are not going out like Crusaders to propagate any great truths. But we are proposing to inform people - to inform many people who would not otherwise be informed; and to inform all people in a manner in which they have never been informed before."

Over the next few months they began working on their proposed news magazine. Every day they cut-up the New York Times and separated the articles into topics. At the end of the week, they extracted the main events and rewrote the stories in their own words. Luce and Hadden showed these mock-ups to their former English professors, Henry Seidal Canby and John Milton Berdan. Canby thought the writing was "positively atrocious" and "telegraphic". Berdan was more sympathetic and accepted that the style was essential if they were to compete with movies, radio shows and billboards. Despite his criticism of the writing, Canby advised the men to continue with the project.

Luce and Hadden resigned their jobs at the Baltimore News-Post and moved back to New York City where they moved in with their parents. They also recruited their friend, Culbreth Sudler, as their business manager. They drew up a prospectus that they could show prospective investors. It included the following: "Time is a weekly news magazine, aimed to serve the modern necessity of keeping people informed, created on a new principle of complete organization. Time is interested - not in how much it includes between its cover - but in how much it gets off its pages into the minds of it's readers." It added that the magazine "would entertain as well as edify" and argued that they would tell the news through the personalities who made the headlines.

A friend of Luce's father introduced them to W. H. Eaton, the publisher of World's Work. He later recalled: "I spent a full afternoon with those fellows going over their first dummy, discussing their editorial philosophy. They certainly were intense about the whole thing, and Hadden seemed to be driving every minute of the time. But it didn't have a professional look to me. I told them I didn't think they'd have a Chinaman's chance." Eaton was so convinced they posed no threat to his magazine, he gave them a list of several thousand of his own subscribers. He also helped them draft a subscription letter that was mailed to a 100,000 people. Of these, over 6,000 people requested trial subscriptions.

Luce and Hadden also had a meeting with John Wesley Hanes, an experienced figure on Wall Street. He told them that it was foolhardy to compete with the highly successful Literary Digest. However, he was especially impressed with Hadden: "Hadden was damned convincing... Luce was there, too. They made a good team. But Luce wasn't much of a talker. He thinks faster than he can talk, you know, and sometimes it gets garbled up. But all the time, Hadden would be in there, selling, selling. He just had what he takes. He was intelligent, he was enthusiastic, he was willing to work and work hard. He was the whole ball of wax rolled into one." Culbreth Sudler agreed that Hadden was very impressive in his dealings with potential investors. He later recalled: "Hadden was interested in everybody. His mind was tireless, and he had an almost unparalleled drive coupled with a strong personal discipline."

Hanes gave them important advice on how to raise money from investors while retaining control of the company. He told them to create two kinds of stock. Preferred stock would pay dividends to investors sooner, but only the common stock would carry the right to vote on company affairs. Under this plan, Hadden and Luce would each keep 2,775 shares - a total of 55.5%, giving them control of the company.

Hadden and Luce used their contacts through the Skull and Bones secret society. A fellow member, Henry Pomeroy Davison, Jr., persuaded his father, Henry Pomeroy Davison, a senior partner at J. P. Morgan, the most powerful commercial bank in the United States at the time, to invest money in the magazine. Davison introduced Luce to fellow partner Dwight Morrow, who also bought stock in the company. Another member, David Ingalls, had married Louise Harkness, the daughter of William L. Harkness, a leading figure in Standard Oil. He had recently died and left $53,439,437 to his family. Louise used some of this money to invest in the magazine. By the summer of 1922 Hadden and Luce had raised $85,675 from sixty-nine friends and acquaintances.

Hadden, who was appointed editor of Time Magazine, now began to acquire his staff. Thomas J. C. Martyn, a former pilot in the Royal Air Force during the First World War, who had lost his leg in an aircraft accident, was given the job of Foreign News editor. He had little experience in journalism but Martyn, who was fluent in French and German, seemed to know a great deal about European politics. Another successful appointment was John Martin, who specialized in writing humorous stories for the magazine. Roy Edward Larsen, was appointed as circulation manager. He had just left Harvard University, where he was business manager of the college literary magazine, The Advocate. Luce had been impressed by the fact that he had been the first person in history to turn it into a profit-making venture.

The first edition of Time Magazine was published on 3rd March, 1923. Only 9,000 copies were sold, a third of what it would take to break even in the first year of business. In an attempt to increase sales, Hadden employed young women to ask for the magazine at news-stands. Their reply was that they had never heard of it. After a few women had requested a copy of the magazine, Hadden arrived and by that time they were in the right mood to take a couple of copies.

According to Isaiah Wilner, the author of The Man Time Forgot (2006): "Gradually Time gained a following among the young and modern set. College students kept the magazine on the coffee tables, circled favorite phrases or surprising facts, and quoted them to friends. A single issue would make its way through several sets of hands." After six months the magazine was selling 19,000 copies a week. By March 1925, Time Magazine had a paid circulation of 70,000 subscribers. In its second year, the magazine made a profit of $674.15.

Despite an increase in revenue, Henry Luce still had trouble paying suppliers. Roy Edward Larsen was asked to come up with a way of finding more income from advertising in the magazine. Hadden suggested the idea of increasing the price of smaller adverts and offering a discount for buying in bulk. This method not only improved revenue but eventually became the industry standard for selling advertising. Larsen devised several different subscription offers. This included paying the cost of postage. The company also supplied a self-addressed and stamped postcard in their mailing.

Although Time Magazine claimed it provided an objective view of the world, its editor, Hadden, always sided with the underdog. He ran several stories on the lynching of black men in the Deep South. He also attacked James Thomas Heflin of Alabama, the leading proponent of white supremacy in the Senate. His reporting on race relations provoked complaints from readers who held conservative views on politics. One reader, Barlow Henderson of South Carolina, accused the magazine of a "flagrant affront to the feelings of our people". His main objection was to the policy of giving black people the respectful title of "Mr."

Hadden hired a team of four young women to do research. They searched through newspapers and books in search of revealing details that they would then pass onto the journalists. The women also had the job of checking the facts of the articles before they were published in the magazine. The researchers were paid half the wages of the journalists on the magazine and Hadden was therefore able to cut the size of the payroll.

Time Magazine targeted the upwardly mobile. It was particularly successful with the younger set of upper-class readers. Hadden wrote that he was not interested in obtaining those readers who read tabloid newspapers. He described them as "gum-chewers, shop girls, taxi drivers, street sheiks, and bummers".

Hadden, the editor of the magazine, created a new style of writing. He was a savage editor who stripped the sentence down, cut extraneous clauses, and used only active verbs. He also removed inconclusive words words like "alleged" and "reportedly". Hadden also liked using the odd obscure word. The author of The Man Time Forgot (2006) has pointed out: "By sprinkling the magazine with a few difficult words, Hadden subtly flattered his readers and invited them to play an ongoing game. Those with large vocabularies could pat themselves on the back, while the rest guffawed at Time's bright boys and looked the word up."

The editor of Time Magazine was also interested in creating new words. For example, while at Hotchkiss School he described boys who had few friends as being "social light". In his magazine he began using the word "socialite" to describe someone who attempted to be prominent in fashionable society. Hadden wanted a new word for opinion makers. As they thought themselves as wise, he called them by the name of his old Yale prankster group: "pundit". Another word brought into general use was "kudos", the Greek word for magical glory. Henry Luce also developed new words. The most famous of these was "tycoon" to describe successful and powerful businessman. The word was based on "taikun", a Japanese term to describe a general who controlled the country in the name of the emperor.

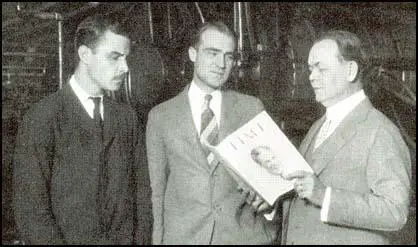

John S. Martin, Thomas J. C. Martyn, Niven Busch and Briton Hadden

Hadden encouraged his writers to use witty epithets to convey the character and appearance of public figures. Grigory Zinoviev was condemned as the "bomb boy of Bolshevism" and Upton Sinclair was called a "socialist-sophist". Winston Churchill was described as being "ruddy as a round full moon". Benito Mussolini was attacked on a regular basis. John Martin commented that when public figures came under attack from Hadden, it was like being "undressed in Macy's window".

Articles in Time Magazine were very different from those found in other newspapers and journals. Isaiah Wilner has pointed out: "Having invented a new writing style that made each sentence entertaining and easy to grasp. Hadden and his writers began to toy with the structure of the entire story. Most newspaper writers tried to tell everything in the first one or two paragraphs. By printing the most important facts first, they destroyed the natural narrative of news. Hadden trained his writers to act as if they were novelist. He viewed the whole story, including the headline and caption, as an information package."

Hadden commented on his relationship with Luce to a friend: "It's like a race. Luce is the best competition I ever had. No matter how hard I run, Luce is always there." Luce was told about this and later he recalled: "If anyone else had said that, I might well have resented the implication that the best I could do was to keep up with him. Coming from Hadden, I regarded it, and still regard it, as the highest compliment I have ever received." Polly Groves, who worked at Time Magazine, remarked: "Everyone who knew Briton Hadden loved him. You couldn't love Henry Luce. You admired him but could not love him."

In March, 1925, Hadden went on a long vacation. The following month Luce discovered that Time Incorporated had lost $1,958.84 over the previous four months. He decided that he could save a considerable sum of money by relocating to Cleveland. John Penton, claimed he could save Luce $20,000 a year by printing the magazine in the city. Luce signed the contract without telling Hadden. When he arrived home from holiday Hadden had a terrible row with Luce. According to Hadden's friends, Luce's action struck a severe blow to their partnership.

Time Magazine moved to Cleveland in August, 1925. The advertising staff remained behind in New York City. Most of the journalists, researchers and office staff refused to relocate. This was partly because Luce refused to pay for their moving expenses. Instead, he sacked the entire staff but offered to reappoint them if they applied for jobs in Cleveland. Thomas J. C. Martyn was furious about the way he was treated and refused to move.

Henry Luce's secretary, Katherine Abrams, commented: Luce is the smartest man I ever knew, but Hadden had the real editorial genius... He was warm and he was human and he had what Luce lacks, an instinct for people." Culbreth Sudler added: "Briton Hadden was Timestyle. It was Timestyle that made Time popular nationwide, and therefore it was Hadden who made Time a success." By 1927 was selling over 175,000 copies a week.

In 1928 the two men argued about business matters. Henry Luce was keen to publish a second magazine that he wanted to call Fortune. Hadden was opposed to the idea of publishing a journal devoted to promoting the capitalist system. He considered the "business world to be vapid and morally bankrupt". Together, Hadden and Luce owned more than half of the voting stock and were able to retain control of the company. However, Luce was unable to publish a new magazine without the agreement of his partner.

In December 1928 Briton Hadden became so ill he was unable to go into the office. Doctors diagnosed him with an infection of streptococcus. Hadden believed he had contracted the illness by picking up a wandering tomcat and taking it home to feed it. The ungrateful cat attacked and scratched Hadden. Another possibility was that he had been infected when he had a tooth removed. The following month he was taken to Brooklyn Hospital. Doctors now feared that the bacteria had spread through his blood-stream to reach his heart.

Henry Luce visited Hadden in hospital and tried to buy his shares in the company. Nurses reported that these conversations ended up in shouting matches. One nurse recalled that Hadden and Luce had yelled at each other so loudly that they could be heard from behind the closed door. Doctors believed that Hadden was wasting his precious energies in these arguments and it was partly responsible for his deteriorating condition.

On 28th January, 1929, Hadden contacted his lawyer, William J. Carr and asked him to draw up a new will. In the document, Hadden left his entire estate to his mother. However, he added that he forbade her from selling the stock in Time Incorporated for forty-nine years. His main objective was to prevent Luce from gaining control of the company they had founded together.

Henry Luce visited Hadden every day. He later recalled: "The last time or two that I was there, I guess I knew he was dying and maybe he did. It seemed to me that he knew and every now and again was wanting to say something, whatever it might be he wanted to say in the way of parting words or something. But he never did, so that there was never any open recognition between him and me that he was dying."

Briton Hadden died of heart failure on 27th February, 1929. The following week Hadden's name was removed from Time's masthead as the joint founder of the magazine. Luce also approached Hadden's mother about buying her stock in Time Incorporated. She refused but her other son, Crowell Hadden, accepted his offer to join the board of directors. Crowell agreed to try and persuade his mother to change her mind and in September 1929, she agreed to sell her stock to a syndicate under Luce's control for just over a million dollars. This gave him a controlling interest in the company.

Primary Sources

(1) Prospectus of Time Magazine (1922)

Time is a weekly news magazine, aimed to serve the modern necessity of keeping people informed, created on a new principle of complete organization. Time is interested - not in how much it includes between its cover - but in how much it gets off its pages into the minds of it's readers.

(2) Isaiah Wilner, The Man Time Forgot (2006)

Having invented a new writing style that made each sentence entertaining and easy to grasp. Hadden and his writers began to toy with the structure of the entire story. Most newspaper writers tried to tell everything in the first one or two paragraphs. By printing the most important facts first, they destroyed the natural narrative of news. Hadden trained his writers to act as if they were novelist. He viewed the whole story, including the headline and caption, as an information package.