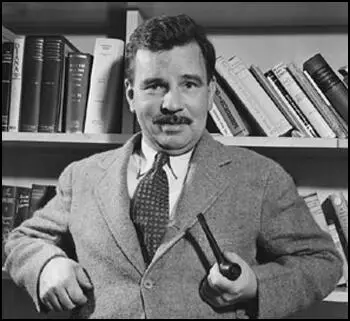

Malcolm Cowley

Malcolm Cowley, the only child of a homeopathic physician, was born in Cambria County, Pennsylvania, on 24th August, 1898. A successful school student, Cowley won a scholarship to Harvard University in 1915. While at university Cowley contributed to the Harvard Advocate and attended lectures by Amy Lowell.

In 1917 Cowley left Harvard to drive munitions trucks for the American Field Service in France. While on the Western Front Cowley wrote articles about the First World War for The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

Cowley returned to the United States in 1918 and soon afterwards met the artist, Peggy Baird. She was briefly married to Orrick Johns but after a visit to Europe she left him and settled in New York City where she mixed with a group of radicals that lived in Greenwich Village. This included Michael Gold, Dorothy Day and Eugene O'Neill. Cowley married Peggy in 1919. He continued with his studies and graduated from Harvard in 1920. For the next few years he wrote poetry and book reviews for The Dial and the New York Evening Post.

In 1921 Cowley moved to France and continued his studies at the University of Montpellier. He also found work with avant-garde literary magazines such as Broom and Secession. While in France he became friendly with American expatriates such as Gertrude Stein, Ernest Hemingway and Ezra Pound.

Cowley returned to the United States in August 1923 and went to live in Greenwich Village where he became close friends with the poet Hart Crane. As well as writing poetry Cowley found work as an advertising copywriter with Sweet's Architectural Catalogue. He also translated seven books from French into English.

In 1929 Cowley published Blue Juniata, his first book of poems. Later that year he replaced Edmund Wilson as literary editor of the New Republic. Cowley's marriage broke up in 1931 and Peggy Baird went to live with Hart Crane in Mexico. This ended in tragedy when Crane committed suicide by jumping from the ship Orizaba on the way back to New York City on 27th April 1932. Two months later Cowley married Muriel Maurer.

Coming under the influence of Theodore Dreiser, Cowley became increasingly involved in radical politics. In 1932 Cowley joined Mary Heaton Vorse, Edmund Wilson and Waldo Frank as union-sponsored observers of the miners' strikes in Kentucky. The men's lives were threatened by the mine owners and Frank was badly beaten up. The following year Cowley published Exile's Return in 1933. The book was largely ignored and sold only 800 copies in the first twelve months. The following year he published an autobiography, The Dream of Golden Mountains (1934).

In 1935 Cowley and other left-wing writers established the League of American Writers. Other members included Erskine Caldwell, Archibald MacLeish, Upton Sinclair, Clifford Odets, Langston Hughes, Carl Sandburg, Carl Van Doren, Waldo Frank, David Ogden Stewart, John Dos Passos, Lillian Hellman and Dashiell Hammett. Cowley was appointed vice president and over the next few years Cowley was involved in several campaigns, including attempts to persuade the United States government to support the republicans in the Spanish Civil War. However, he resigned in 1940 because he felt the organization was under the control of the American Communist Party.

In 1941 President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Archibald MacLeish as head of the Office of Facts and Figures. MacLeish recruited Cowley as his deputy. This decision soon resulted in right-wing journalists such as Whittaker Chambers and Westbrook Pegler writing articles pointing out Cowley's left-wing past. One member of Congress, Martin Dies of Texas, accused Cowley of having connections to 72 communist or communist-front organizations.

MacLeish came under pressure from J. Edgar Hoover, head of the FBI, to sack Cowley. In January 1942, MacLeish replied that the FBI agents needed a course of instruction in history. "Don't you think it would be a good thing if all investigators could be made to understand that Liberalism is not only not a crime but actually the attitude of the President of the United States and the greater part of his Administration?" In March 1942 Cowley, vowing never again to write about politics, resigned from the Office of Facts and Figures.

Cowley now became literary adviser to Viking Press. He now began to edit the selected works of important American writers. Viking Portable editions by Cowley included Ernest Hemingway (1944), William Faulkner (1946) and Nathaniel Hawthorne (1948). In 1949 Cowley returned to the political scene by testifying at the second Alger Hiss trial. His testimony contradicted the main evidence supplied by Whittaker Chambers.

Cowley published a revised edition of Exile's Return in 1951. This time the book sold much better. He also published The Literary Tradition (1954) and edited a new edition of Leaves of Grass(1959) by Walt Whitman. This was followed by Black Cargoes, A History of the Atlantic Slave Trade (1962), Fitzgerald and the Jazz Age (1966), Think Back on Us (1967), Collected Poems (1968), Lesson of the Masters (1971) and A Second Flowering (1973).

Malcolm Cowley died on 28th March 1989.

Primary Sources

(1) Malcolm Cowley, Exile's Return (1934)

When the war came the young writers then in college were attracted by the idea of enlisting in one of the ambulance corps attached to a foreign army - the American Ambulance Service or the Norton-Harjes, both serving under the French and receiving French army pay, or the Red Cross ambulance sections on the Italian front. Those were the organizations that promised to carry us abroad with the least delay. We were eager to get into action, as a character in one of DOS Passos's novels expressed it, "before the whole thing goes belly up."

In Paris we found that the demand for ambulance drivers had temporarily slackened. We were urged, and many of us consented, to join the French military transport, in which our work would be not vastly different: while driving munition trucks we would retain our status of gentleman volunteers. We drank to our new service in the bistro round the corner. Two weeks later, on our way to a training camp behind the lines, we passed in a green wheatfield the grave of an aviator mort pour la patrie, his wooden cross wreathed with the first lilies of the valley. A few miles north of us the guns were booming. Here was death among the flowers, danger in spring, the sweet wine of sentiment neither spiced with paradox nor yet insipid, the death being real, the danger near at hand.

It would be interesting to list the authors who were ambulance or camion drivers in 1917. DOS Passes, Hemingway, Julian Green, William Seabrook, E. E. Cummings, Slater Brown, Harry Crosby, John Howard Lawson, Sidney Howard, Louis Bromfield, Robert Hillyer, Dashiell Hammett - one might almost say that the ambulance corps and the French military transport were college-extension courses for a generation of writers. But what did these courses teach?

They carried us to a foreign country, the first that most of us had seen; they taught us to make love, stammer love, in a foreign language. They fed and lodged us at the expense of a government in which we had no share. They made us more irresponsible than before: livelihood was not a problem; we had a minimum of choices to make; we could let the future take care of itself, feeling certain that it would bear us into new adventures. They taught us courage, extravagance, fatalism, these being the virtues of men at war; they taught us to regard as vices the civilian virtues of thrift, caution and sobriety; they made us fear boredom more than death. All these lessons might have been learned in any branch of the army, but ambulance service had a lesson of its own: it instilled into us what might be called a spectatorial attitude.

(2) Malcolm Cowley, Exile's Return (1934)

When we first heard of the Armistice we felt a sense of relief too deep to express, and we all got drunk. We had come through, we were still alive, and nobody at all would be killed tomorrow. The composite fatherland for which we had fought and in which some of us still believed - France, Italy, the Allies, our English homeland, democracy, the self- determination of small nations - had triumphed. We danced in the streets, embraced old women and pretty girls, swore blood brotherhood with soldiers in little bars, drank with our elbows locked in theirs, reeled through the streets with bottles of champagne, fell asleep somewhere. On the next day, after we got over our hangovers, we didn't know what to do, so we got drunk. But slowly, as the days went by, the intoxication passed, and the tears of joy: it appeared that our composite fatherland was dissolving into quarreling statesmen and oil and steel magnates. Our own nation had passed the Prohibition Amendment as if to publish a bill of separation between itself and ourselves; it wasn't our country any longer. Nevertheless we returned to it: there was nowhere else to go. We returned to New York, appropriately - to the homeland of the uprooted, where everyone you met came from another town and tried to forget it; where nobody seemed to have parents, or a past more distant than last night's swell party, or a future beyond the swell party this evening and the disillusioned book he would write tomorrow.

(3) In April 1931 Theodore Dreiser invited a group of left-wing writers to his home. Malcolm Cowley wrote about the event in his autobiography, The Dream of Golden Mountains (1934)

Dreiser stood behind a table and rapped on it with his knuckles. He unfolded a very large, very white linen handkerchief and began drawing it first through his left hand, then through his right hand, as if for reassurance of his worldly success. He mumbled something we couldn't catch and then launched into a prepared statement. Things were in a terrible state, he said, and what were we going to do about it? Nobody knew how many millions were unemployed, starving, hiding in their holes. The situation among the coal miners in Western Pennsylvania and in Harlan County, Kentucky, was a disgrace. The politicians from Hoover down and the big financiers had no idea of what was going on. As for the writers and artists - Dreiser looked up shyly from his prepared text, revealing his scrubbed lobster-pink cheeks and his chins in retreating terraces. For a moment the handkerchief started moving.

The time is ripe," he said, "for American intellectuals to render some service to the American worker." He wondered - as again he drew the big white handkerchief from one hand to the other - whether we shouldn't join a committee that was being organized to collaborate with the International Labor Defense in opposing political persecutions, lynchings, and the deportation of labor organizers; also in keeping the public informed and in helping workers to build their own unions. Then, after some inaudible remarks, he declared that he was through speaking and that we were now to have a discussion.

(4) Malcolm Cowley, The Dream of Golden Mountains (1934)

In July he (Theodore Dreiser) made an expedition to the Western Pennsylvania coalfields, where the National Miners Union, organized by the Communists, was conducting a hopeless strike. He issued a violent and merited rebuke to the American Federation of Labor for neglecting the miners. Early in November, in his capacity as chairman of the NCDPP, he led a delegation of writers (Malcolm Cowley, Edmund Wilson, Waldo Frank, Mary Heaton Vorse) into Harlan County, Kentucky, another area that the Communist union was trying hard to organize.

Harlan was a classical example of labor warfare in a depressed industry. The market for coal had been shrinking, with the result that the operators had tried to protect their investments by cutting wages, and also - since the miners were paid for each ton they produced - by using crooked scales to weigh the coal. In 1931 very few of the eastern Kentucky miners were earning as much as $35 a month, after deductions. Even that miserable wage was paid, not in cash, but in scrip, good only at the company store and worth no more, in most cases, than fifty or sixty cents on the dollar.

The United Mine Workers - John L. Lewis's union - had withdrawn from the field, apparently on the ground that the situation was hopeless and that the miners couldn't afford to pay their union dues. Then the Communists had stepped in, as they often did in hopeless situations, but their meetings were broken up by deputized thugs armed with Browning guns.

(5) Malcolm Cowley, The Dream of Golden Mountains (1934)

A few weeks later there was more talk of revolution when the Bonus Expeditionary Force descended on Washington. The BEF was a tattered army consisting of veterans from every state in the Union; most of them were old-stock Americans from smaller industrial cities where relief had broken down. All unemployed in 1932, all living on the edge of hunger, they remembered that the government had made them a promise for the future. It was embodied in a law that Congress had passed some years before, providing "adjusted compensation certificates" for those who had served in the Great War; the certificates were to be redeemed in dollars, but not until 1945. Now the veterans were hitchhiking and stealing rides on freight cars to Washington, for the sole purpose, they declared, of petitioning Congress for immediate payment of the soldiers' bonus. They arrived by hundreds or thousands every day in June. Ten thousand were camped on marshy ground across the Anacostia River, and ten thousand others occupied a number of half-demolished buildings between the Capitol and the White House. They organized themselves by states and companies and chose a commander named Walter W. Waters, an ex-sergeant from Portland. Oregon, who promptly acquired an aide-de-camp and a pair of highly polished leather puttees. Meanwhile the veterans were listening to speakers of all political complexions, as the Russian soldiers had done in 1917. Many radicals and some conservatives thought that the Bonus Army was creating a revolutionary situation of an almost classical type.