Victor Grayson

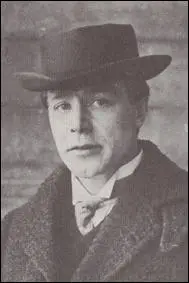

Albert Victor Grayson, the seventh son of William Grayson, a carpenter, and his mother Elizabeth Craig Grayson, was born in Liverpool on 5th September, 1881. According to his biographer, David Clark, some people have claimed that he was the "love child of one of the English aristocracy and that he had been placed with Mrs Grayson in exchange for financial assistance". (1)

Another source claims he was related to Winston Churchill. (2) According to Jane, who worked for the Grayson family, was told by Elizabeth Grayson that Victor's father was George Spencer-Churchill, 8th Duke of Marlborough. (3)

Grayson was educated at St Mathew's Church of England School on Scotland Road. As a child he suffered from a stammer and was teased about it at school. (4) At the age of fourteen he ran away from home and attempted to stow away on board a ship bound for Australia. After four days at sea he was discovered and returned to his parents. (5)

In 1899 Grayson started work as an apprentice engineer in Bootle, Lancashire. He joined the union and over the next couple of years became very interested in the emerging socialist movement. However, his mother was deeply religious and wanted him to become a church minister and in 1904 he entered Owen's College in Manchester to train for the Unitarian ministry. (6)

Grayson attended services at the Bethel Mission and he was soon gaining his earliest experience in public speaking, first as a Sunday School teacher, and then by addressing outdoor Christian meetings. (7) Grayson later told William Stead, the editor of the Pall Mall Gazette that he decided to concentrate on his political activities: "It was useless to expect true religion in a social system such as the present - better conditions could only come by political action.... I was determined that my university career was to be a really useful one. I must agitate among my fellow students." (8)

Grayson learnt about politics by reading The Clarion, Justice and The Labour Leader. Grayson also attended meetings of the Socialist Debating Society at the Liverpool Mission Hall and made speeches in the college. One of his fellow students pointed out: "If the word went round that Grayson was talking in the Common Room we would flock down in crowds... it was all socialism, it was a kind of religion with him." (9)

Victor Grayson and the Independent Labour Party

Grayson joined the Independent Labour Party (ILP). Formed in 1893 the main objective of the ILP was "to secure the collective ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange". Leading figures in this organisation included Keir Hardie, Robert Smillie, George Bernard Shaw, Tom Mann, George Barnes, Bruce Glasier, H. H. Champion, Ben Tillett, Edward Carpenter and Ramsay Macdonald. (10)

In Liverpool Grayson developed a reputation as a superb orator. Most days he could be found standing on his soap box giving lectures on socialism. The university authorities became concerned about Grayson neglecting his studies and asked one of the ILP leaders, Philip Snowden, to speak to him. Snowden was unable to persuade Grayson to continue his studies. Grayson told Snowden that the university was a "make-believe refuge" and he intended to work in the real world. Over the next couple of years Grayson toured the industrial districts giving lectures on socialism. His reputation grew and he was seen as a future leader of the recently formed Labour Party. (11)

In August 1905, Grayson wrote to a friend who shared his socialist beliefs: "You've probably read about the unemployment disturbances here. The next few weeks promise some stormy scenes... These are glorious days, Dawson, and we youthful warriors should be brightening our armour and poising for the fight. Lancashire is in a state of seething fermentation and I want God to send a fire to burn up some of the already smouldering rubbish." (12)

Grayson's biographer, David Howell, has pointed out: "Unemployment was high in Manchester during 1905 and Grayson emerged as a popular and effective speaker at demonstrations. His passion for socialism replaced his religious commitment, and in July 1906 he withdrew from his course. Grayson's subsequent political rise was meteoric. In significant respects his experience of the labour movement was narrow. He preferred the emotions of the platform to the humdrum tasks of political organization." (13)

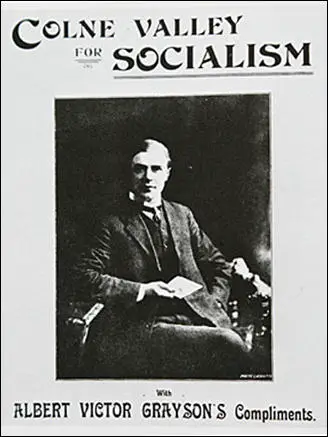

Colne Valley By-Election

In January 1907, the Independent Labour Party in Colne Valley selected Victor Grayson as their parliamentary candidate to replace Tom Mann, who had decided to concentrate on trade union matters. In the past, there had been an arrangement where the labour movement supported the Liberal Party candidate in Colne Valley in return for help in winning other seats for ILP candidates. The executive of the Labour Party therefore decided not to endorse Grayson as their candidate. In choosing their candidate the people of Colne Valley "selected someone with little experience whom they trusted." (14)

Keir Hardie was unhappy with the decision. He wrote to John Bruce Glasier that "I don't like the man they have chosen but that cannot be helped". Hardie later reported: "Mr Grayson's work in the movement, valuable as it had been, was a matter of very few years... There was neither anger nor bias against Mr Grayson, but simply a desire that men who had grown grey in the movement should not feel that they were put aside to make room for younger men." (15)

Victor Grayson became a regular speaker in the town. Kenneth O. Morgan points out that Grayson was "a spell-binding orator, with a kind of film-star charisma, a supreme rebel propelled from nowhere to smash down the crumbling edifice of British capitalism". What was also surprising that he was able to do it in Colne Valley: "How could the solid, respectable, nonconformist cotton and woollen workers of Colne Valley, close to much older forms of industrial production, relatively well-housed and well-paid, and almost all in regular employment allow themselves to be so swept up in the millenarian intensity of Grayson's crusade in 1907?" (16)

The Colne Valley Guardian was shocked by the appeal of Grayson's socialist campaign: "It is somewhat of a paradox but nevertheless true, that the measure of its discontent, and the higher the wages, the more eager is the straining after the chimerical ideals of Socialism. For the last seven or eight years the Colne Valley has enjoyed an unparalleled period of commercial prosperity. That has not been due entirely to the manufacturers, nor yet to the mill-workers but to both combined." (17)

Harry Hoyle, who was only 12 years old at the time, remembers Grayson speaking in the town: "I can picture him now in front of the Co-op at the Market Place in Marsden. They had a wagon for a platform... He seemed so enthusiastic about everything he attempted, he gave you the impression that this is what we want and this is what we must have... it was infectious. It was really. People just went hay-wire. They went mad at his meetings." (18)

Colne Valley ILP refused to back down and in the by-election held in July, 1907, Grayson stood as an Independent Socialist candidate. Only three leading figures in the ILP, Katherine Glasier, Philip Snowden and J. R. Clynes were willing to speak at his meetings during the campaign. As Reg Groves, the author of The Strange Case of Victor Grayson (1975), has pointed out: "The socialists had no money, save the pennies collected amongst their fellow workers in the mills and factories and at meetings. As the campaign grew, money was raised by more desperate measures; watches, household goods, even wedding rings were pawned to keep the supply of money flowing. They had no efficient, smooth working electoral machinery; it had to be improvised on the spot. The trade union machinery which might well have added much in the way of organisation and wide-flung influence was not likely to give its unstinted support, since the Labour Party refused its endorsement; the ILP, too, was antagonistic, and many of the local union officials favoured a policy of working with the Liberals, not against them." (19)

Although the ILP was committed to the parliamentary road to socialism, during the election, Grayson advocated revolution. In his election address Grayson wrote: I am appealing to you as one of your own class. I want emancipation from the wage-slavery of Capitalism. I do not believe that we are divinely destined to be drudges. Through the centuries we have been the serfs of an arrogant aristocracy. We have toiled in the factories and workshops to grind profits with which to glut the greedy maw of the Capitalist class. Their children have been fed upon the fat of the land. Our children have been neglected and handicapped in the struggle for existence. We have served the classes and we have remained a mob. The time for our emancipation has come. We must break the rule of the rich and take our destinies into our own hands. Let charity begin with our children. Workers, who respect their wives, who love their children, and who long for a fuller life for all. A vote for the landowner or the capitalist is treachery to your class. To give your child a better chance than you have had, think carefully ere you make your cross. The other classes have had their day. It is our turn now." (20)

At least forty clergymen worked on Grayson's behalf. His supporters sung Jerusalem, England Arise and The Red Flag at meetings and their main slogan was "Socialism - God's Gospel for Today". (21) One of his most important campaigners was W. B. Graham, the giant curate of Thongsbridge. The left-wing journalist, Robert Blatchford, described him as "six foot a socialist and five inches a parson". Graham's mission was the "Christianizing of Christianity". (22)

Grayson also campaigned for votes for women. Hannah Mitchell joined his campaign and later recalled: "I must have worked the Colne Valley from end to end, often under the auspices of the Colne Valley Labour League. Sometimes we just went... from door to door to ask the women to come and listen (to Victor Grayson), which the Colne Valley women were usually willing to do." (23) Emmeline Pankhurst also visited the town in support of Grayson. (24) The Daily Mirror pointed out that "Colne Valley mill girls... many of them who cared nothing about votes before are now eager in their desire to enjoy the privileges of the franchise." (25)

In one of his speeches Grayson outlined his view on women's suffrage: "The placing of women in the same category, constitutionally, as infants, idiots and Peers, does not impress me as either manly or just. While thousands of women are compelled to slave in factories, etc., in order to earn a living; and others are ruined in body and soul by unjust economic laws created and sustained by men, I deem it the meanest tyranny to withhold from women the right to share in making the laws they have to obey. Should I be honoured with your support, I am prepared to give the most immediate and enthusiastic support to a measure giving women the vote on the same terms as men. This is as a step to the larger measure of complete Adult Suffrage." (26)

The election took place on 18th July, 1907. Almost every eligible registered elector cast his vote and a turn-out of eighty-eight per cent was recorded. Grayson received 3,648 votes and this gave him a majority over his two opponents: Philip Bright - Liberal (3,495) and Grenville Wheeler - Conservative (3,227). The Daily Express reported that Grayson's victory illustrated the "menace of socialism" and reported on 20th July, 1907: "The Red Flag waves over the Colne Valley... the fever of socialism has infected thousands of workers, who, judging from their merriment this evening, seem to think Mr Grayson's return means the millennium for them." (27)

In his victory speech Grayson pointed out: "The very first joy that comes to my mind is this, that this epoch-making victory has been won for pure revolutionary socialism... You have voted, you have worked for socialism: you have voted, you have worked for the means of life to be the property of the whole class instead of a few small classes. We stand for equality, human equality, sexual equality... It is a splendid victory comrades." (28)

Wilfred Whiteley was a local member of the ILP: "The winning of Colne Valley was largely due to his vivacity and his enthusiasm, and his youth; and it just carried the day. I would say that it was almost entirely the platform work of Grayson that gave him his appeal, and that led people to follow him, and of course his great capacity for telling stories really attracted the listeners to a tremendous degree." (29)

House of Commons

The Independent Labour Party and the Social Democratic Federation welcomed Grayson's victory as it showed that a revolutionary socialist could be elected to Parliament. The Labour Party was unhappy with Grayson's victory as it posed a threat to their relationship with the Liberal Party. In the House of Commons he attacked the gradualism of the Labour Party: "We are advised to advance imperceptibly - to go at a snail's pace - to take one step at a time. Surely there are some young enough to take two steps or more at a time." (30)

In his maiden speech in the House of Commons Grayson criticised the recent decision to grant the diplomat, Evelyn Baring, the 1st Earl of Cromer, £50,000 for his services in Egypt. He attacked the government for rewarding a man for "consolidating Imperialism". Grayson added that Cromer had already been well-paid "while outside the four walls of this House people are dying of starvation". Pointing to the government front-bench he said he was looking forward to the day when those seats "will be occupied by socialists, sent there by an indignant people".

On Tuesday, 31st October, 1908, Grayson stood up in the House of Commons and shouted out: "I wish to move the adjournment of the House so that it can deal with the unemployment question... people are starving in the streets." When he refused to sit down he was escorted from the Commons. As he left he turned to Labour members and shouted: "You are traitors! Traitors to your class." (31)

Grayson was now suspended from the House of Commons. Grayson's actions gained the approval of people like George Bernard Shaw, but provoked predictable hostility from Labour members. (32) "Grayson's activities were profoundly embarrassing to his colleagues, both because these activities were deemed to compromise the Labour Group's respectability, and also because they offered to the activists a striking contrast with the Group's own lack of impact." (33)

Keir Hardie, the leader of the ILP, was quick to make it clear that he completely rejected the tactics of Victor Grayson: "Grayson came to the House of Commons, consulted no one and did not even intimate that he meant to make a scene. This may be his idea of comradeship; it is not mine." J. R. Clynes added: "I do not believe causes are served by violent language and violent action." (34)

Fred Jowett also attacked Grayson for his behaviour. "Men are now described as traitors by Victor Grayson who undertook the task of founding a Socialist Movement at a time when the chilling frost of almost universal indifference was far harder to bear than are the violent alternations between the excitement of hostility and the enthusiasm of fellowship in which Victor Grayson now lives and moves. We must recognise that the man who can make a crowd shout is not necessarily an organizer of men. The gift of platform oratory, skill in making striking phrases, is a dangerous one. It is the man behind that matters. If his skill is employed in setting, not class against class, but men of the same class against their kith and kin, sewing seeds of distrust and hatred where the love of a common cause should produce the fellowship of kindred spirits, it were better if he had no such skill." (35)

Theodore Rothstein was more sympathetic to Victor Grayson but attacked him for not accepting Marxism: "Grayson is still quite a young man, about 27 years old, gifted, full of temperament, a born agitator, but without any sort of theoretical knowledge, no Marxist – more inclined to be an opponent of Marxism – in short, a sentimental Socialist at an age when the wine is not yet fermented. Like all Socialists of this type – and the type is a historical one, dating far back beyond our period – he represents more the tribune of the people than the modern party man, and without being an anarchist or syndicalist, he has a great horror of parliamentarism and of the planned political struggle, which he looks upon as dirty jobbery. This horror seems to be very wide-spread in England, in spite of the prevalent fetish-worship of Parliament, and is caused by the lying and deceitful tactics of the bourgeois parties." (36)

Edward Carpenter got to know him during this period: "Victor Grayson was a most humorous creature. His fund of anecdotes was inexhaustible, and rarely could a supper party of which he was a member got to bed before three in the morning. On the platform for detailed or constructive argument he was no good, but for criticism of the enemy he was inimitable - the shafts of his wit played like lightening round him, and with his big mouth and flexible upper lip he seemed to be simply browsing off his opponents and eating them up." (37)

His biographer, David Howell, has argued: "Often charming, and attractive to both men and women, his politics lacked depth. For his sympathizers he represented the hope of a better world that owed more to moral conversion than to legislation; for his detractors he represented the irrational, the destabilizing, and the potentially violent both as pre-war socialist and as wartime patriot. From one standpoint he is the flawed socialist hero; but his distinctive trajectory also illuminates specific and important themes within the Edwardian left. A character in a morality play, he was nevertheless very much a man of his time and place." (38)

Grayson was angry that the national leadership had been unwilling to support his campaign in Colne Valley and refused to join the Labour Party group in the House of Commons. In fact, Grayson rarely attended Parliament, preferring to tour the country making speeches in favour of revolutionary socialism. Of over 300 debates that took place in the Commons while he was the Colne Valley MP, Grayson only voted in 32. Grayson behaviour in Parliament was also becoming more erratic and it became clear that he had a serious drink problem. (39)

After this incident Grayson rarely visited the House of Commons and spent most of his time writing for The Clarion or being paid for making speeches. David Clark has argued: “He was young, dynamic and good-looking. His oratory was brilliant. In a political scene and age which abounded with brilliant orators, Grayson excelled. Some have suggested he was the greatest mob orator of his time. He could easily carry a crowd with him. He seldom used notes and had that rare gift of being able to marshal his thoughts logically while on his feet. Grayson’s style caught the mood of dissent and dissatisfaction of Edwardian England, not only among working people but also among the middle classes. His approach to politics and socialism was that of an evangelical preacher. He offered hope to thousands of men and women who toiled incessantly in hard labour for meagre rewards.” (40)

Defeat in 1910 General Election

At first the people of Colne Valley were pleased that they had an MP that spoke up for the unemployed. However, they were less impressed by stories his luxurious life-style and his heavy drinking and he had fewer volunteers to help him in the 1910 General Election. One man who did campaign for him was John McNair. He later wrote that he was shocked by the sight of Grayson attending meetings drunk. "It was a terrible blow to me, a young enthusiastic socialist from a working-class family." (41)

The Liberal Party fought the election on the subject of reforming the House of Lords who had tried to block the radical People's Budget. Socialists tended to agree with the Liberals on this issue. Charles Leach, the Liberal candidate, won the election with 4,741. The Tory was second and Grayson finished at the bottom of the poll with 3,149 votes. He was not alone, in the election Labour candidates only won seats not contested by Liberals. Whenever socialist candidates fought both parties, they finished at the bottom of the poll. (42)

Victor Grayson made a speech where he claimed he would win the next election in Colne Valley: "The day is coming when socialism, the hope of the world, the future religion of humanity, will have wiped Liberalism and Toryism from the face of the earth... Sick to your flag... Don't let our colours be stained... Stick to the gospel that first inspired your heart and you will live to rejoice in a victory that none can gainsay." (43)

Grayson left the Independent Labour Party and talked about forming a new party. He argued: "We must have a Socialist Party... to demand the right to work; a Party to demand the right to live; a Party whose hatred of capitalism is implacable and undying... It is war - war to the knife... We are out to fight, to win." (44)

The British Socialist Party (BSP) was formed in September 1911. H. M. Hyndman, the former leader of the Social Democratic Federation, became one of its most significant members. Another important figure was Harry Quelch, who Grayson described as a "pugnacious intellectual bulldog". Grayson said he wanted a party of the sort where, united on socialism, differences could be allowed on pacifism, vegetarianism and similar matters of dispute". Robert Blatchford and his newspaper, The Clarion, supported the new party." (45)

Arthur Rose, Victor's closest friend, later claimed that women found him very attractive. "I knew a great deal about Victor's many relationships with women. You can't blame Victor. He attracted women: he was, well, like a matinee idol... he had the loveliest women in the movement - and outside it too - throwing themselves at him. He was only human... Victor felt, as I did, that we ought to be free to devote all our time to the cause. We were both heart and soul in the socialist movement; we lived for nothing else." (46)

On 7th November, 1912, Victor Grayson married the actress, Ruth Nightingale. (47) Ruth was the daughter of John Webster Nightingale, a wealthy banker. (48) One of Victor's close friends told Reg Groves that women had been a constant problem for him during his political career. "Women followed him, worried him... he could not help attracting them - like Ramsay MacDonald who was a fine looking man - they flocked around him all the time: I blame the women, mind, I blame the women, they wouldn't leave him be... He never should have married Ruth Nightingale - a nice girl, but not the sort for Victor. I don't think they got on too well." (49)

According to his biographer, David Clark, Victor Grayson had homosexual tendencies: "It is now known that he had such a relationship with his Merseyside friend Harry Dawson. Throughout his life there is evidence of this duality in Victor's character - he was obviously bisexual. While there was a series of relationships with women, his happiest periods were when he was in male company." (50)

Without a seat in the House of Commons, Victor Grayson attempted to make a living from lecture tours. Still drinking heavily, his health began to deteriorate. Many socialists felt that he had let them down: "We all trusted him... he was the darling of the socialist movement: none of our champions was ever made so much of... He possessed so many of the qualities of leadership... genial, hearty, with a homely wit and eloquence... Grayson rallied round him a following of which any man might be proud." (51)

In 1913 Grayson gave up alcohol and went on a sea-cruise and for a while his health began to recover. He was now strong enough to start a lecture tour in America. This went well until he started drinking again. Grayson returned to Britain but he was now an alcoholic and at public meetings in Bradford and Glasgow he was too drunk to speak and had to be carried off the stage. Even the birth of a daughter in April 1914, failed to stop him drinking and soon afterwards he was declared bankrupt with debts of £451. (52)

First World War

Grayson began making speeches concerning the dangers of the "German menace" and urging preparations to meet the growing naval and military power of Germany. He argued: "Rightly or wrongly, some of us suspect that a war with one, or a combination of European powers, is possible, if not inevitable. Rightly or wrongly some of us suspect that a war would find us unready and inadequately equipped. We believe that the maintenance of the British Empire offers the best conditions for the world's march towards socialism." (53)

At the end of July, 1914, it became clear to the British government that the country was on the verge of war with Germany. Four senior members of the government, Charles Trevelyan, David Lloyd George, John Burns and John Morley, were opposed to the country becoming involved in a European war. They informed the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, that they intended to resign over the issue. When war was declared on 4th August, three of the men, Trevelyan, Burns and Morley, resigned, but Asquith managed to persuade Lloyd George, his Chancellor of the Exchequer, to change his mind. Trevelyan went on to establish the anti-war organisation, the Union of Democratic Control. (54)

All of the socialist leaders in Britain opposed the war. Keir Hardie made a speech on 2nd August, 1914, where he called on "the governing class... to respect the decision of the overwhelming majority of the people who will have neither part nor lot in such infamy... Down with class rule! Down with the rule of brute force! Down with war! Up with the peaceful rule of the people!" (55)

Ramsay MacDonald also stated that he would not encourage his members to take part in the war. "Out of the darkness and the depth we hail our working-class comrades of every land. Across the roar of guns, we send sympathy and greeting to the German Socialists. They have laboured increasingly to promote good relations with Britain, as we with Germany. They are no enemies of ours but faithful friends." (56)

Almost alone amongst left-wing political figures, Grayson gave recruiting speeches and wrote articles urging young men to join the armed forces. Some socialists accused him of being paid by the government to make these speeches. He attempted to explain why he changed his views on war: "This war has made havoc of many ready-made theories and doctrines, and some of my most cherished antipathies have succumbed to its effects. I am facing the fact that some 178 Peers of the Realm are now in khaki fighting an enemy country." (57)

In 1915 Grayson travelled to Australia and New Zealand where he gave speeches in favour of conscription. "Not only did his pro-conscription views prove unpopular, but his speeches could be marred by alcohol, and there were allegations of financial deception." (58) He was denounced by the anti-war movement as being well-paid by government sources for making these speeches." (59)

In an interview Grayson gave to the Christchurch Sun he argued that the working-class would be rewarded if the Allied forces won the war: "The war has cast everything into the crucible. So far as Socialism can be defined intelligently, I still believe that the products of the workers belong to the workers... The war has wrought a marvellous change in the division of classes and masses. The working man has changed his attitude towards the worker, hence new political, industrial and ethical conditions will be the result of our inevitable triumph." (60)

A left-wing journalist commented about how the audience reacted in Wellington: "The audience laughed at his jokes and applauded his hits at the capitalist system. It was a good meeting, but our comrade was certainly out of touch with his audience on the military question, and some of those present let him know it. Rightly or wrongly, we have built up a very strong anti-militarist sentiment in the Holy City (Wellington), and anyone who comes here must be prepared to state their opinions on the question." (61)

Grayson's campaign continued and a long interview appeared in The Lyttleton Times on 4th October 1916. "Wage-earners and capitalists were fighting side-by-side in the ranks, and the capitalist was acquiring the habit of regarding the wage-earners in a very different light from that in which he saw them in the days before the war. War had brought the socially antagonistic classes into closer relations, and the result of the closer knowledge and understanding could not but be beneficial to humanity." (62)

The following month he launched an attack on socialists who opposed military conscription: "Needless to say, the Socialist-Pacifists are anti-conscriptionists, but their real disease is anti-militarism. If a fire broke out in their domestic abodes they would talk to it gently. If a German assaulted their wives or daughter, or if a Prussian crushed the skulls of their babes... they would explain that such conduct was not in keeping with the spirit of the international. I am a Socialist and a democrat to the very roots of my being, but I confess that my bosom comrades are entirely incomprehensible to me. The Labour Party in New Zealand had the chance of their lifetime when the horrid word conscription was mooted. They could and should have accepted the conscription of men, on the guarantee of the Dominion Parliament to conscript capital and wealth... The pacifist (whether he calls himself a Socialist or Quaker) is a greater menace than the guttural Hun in the trenches of Flanders... I hate war and I hate killing. Yet if I account for one of the vassals of the world's mad-dog I shall have done my bit towards world regeneration." (63)

Later that month Victor Grayson enlisted in the New Zealand Army. He explained his decision in a speech: "The pay is good and the chances of getting into a good fight are excellent. I am a socialist and will wear the uniform of a warrior with a good logic and a bright spirit. I hate war and hate killing, yet if I account for one of the vassals of the world's mad dog, I shall have done my bit towards the world's restoration." (64)

Grayson arrived in France in September, 1917. He was sent to the Western Front and on 12th October 1917 at Passchendaele, he was sent over the top for the first time and soon afterwards a shell burst near him, leaving him slightly concussed and with a piece of shrapnel embedded in his hip. (65) According to army records, the mud was knee deep and the stretcher-bearers found it very difficult to bring out the wounded. It was taking six to seven hours to carry a stretcher the three miles to the dressing station. (66)

Grayson later told The Daily Mail that by the time he reached the advanced dressing station, the staff were either dead or badly wounded. Grayson claimed that "covered from head to foot in clinging slime" he was put on a horse and he rode to the three miles to the next dressing station. After receiving medical treatment he was sent to Brockenhurst Hospital to have the shrapnel removed. (67)

Friends claim that although he was only on the front-line for a few weeks he was suffering from shell-shock. On 15th December, 1917, it was recommended that he should be discharged from the army as physically unfit as he was suffering from neurasthenia (a generic term in 1918 for such nervous afflictions as those resulting from shell-shock).

On 6th February 1918, Ruth Grayson gave birth prematurely to a daughter, Elise, who unsuccessfully struggled for life for a brief fifteen minutes. Ruth survived the actual birth, but four days later on 10 February she died from the after-effects of childbirth in a nursing home at 42 Belgrave Road in London. (68)

Disappearance of Victor Grayson

After the war Victor Grayson returned to England where he hoped to revive his political career. Without the backing of any of the major political parties, Grayson found it impossible to become a parliamentary candidate. Grayson took a keen interest in Irish politics and made several secret trips to Ireland where he had talks with Michael Collins. He told Robert Blatchford that he wanted to become a full-time journalist and was investigating the Roger Casement case. (69)

In early 1918 Basil Thomson, head of the Special Branch, asked one of his agents, Arthur Maundy Gregory to spy on Grayson, who he described as a "dangerous communist revolutionary". Gregory was told: "We believe this man may have friends among the Irish rebels. Whatever it is, Grayson always spells trouble. He can't keep out of it... he will either link up with the Sinn Feiners or the Reds." Gregory was a regular visitor to Grayson's home and David Clark, the author of Victor Grayson: Labour's Lost Leader (1985) has suggested he might have been recruited by MI5 to spy on the Labour Party. (70)

Reg Groves claims that the two men were enemies. However, another biographer, David Howell, believes it is possible that Gregory was paying Grayson money. "Grayson subsequently lived in apparent affluence - a contrast with his recent poverty - in a West End flat. His associates included Maundy Gregory... The significance of this relationship and the source of Grayson's income remain unknown." (71)

Grayson believed he was working for Gregory but during the summer of 1919 he became aware that he was being spied upon. He told a friend: "Just as he spied on me, so now I'm spying on him. One day I shall have enough evidence to nail him, but it's not going to be easy." Grayson came to the conclusion that Gregory was involved in a corrupt relationship with David Lloyd George, the British Prime Minister. (72)

In September, 1920, Grayson made a speech where he accused Lloyd George, of corruption. Grayson claimed that Lloyd George was selling political honours for between £10,000 and £40,000. Grayson declared: "This sale of honours is a national scandal. It can be traced right down to 10 Downing Street, and to a monocled dandy with offices in Whitehall. I know this man, and one day I will name him." The monocled dandy was Arthur Maundy Gregory, who had indeed been selling honours on behalf of Lloyd George. (73)

A few days later Victor Grayson was beaten up in the Strand. This was probably an attempt to frighten Grayson but he continued to make speeches about the selling of honours and threatening to name the man behind this corrupt system. On the 28th September, Grayson was drinking with friends when he received a telephone message. Grayson told his friends that the had to go to Queen's Hotel in Leicester Square and would be back shortly. (74)

Later that night, George Jackson Flemwell was painting a picture of the Thames, when he saw Grayson entering a house on the river bank. Flemwell knew Grayson as he had painted his portrait before the war. Flemwell did not realize the significance of this as the time because Grayson was not reported missing until several months later. An investigation carried out in the 1960s revealed that the house that Grayson entered was owned by Arthur Maundy Gregory. (75) (15)

Hilda Porter, the manageress of Grayson's apartment in Vernon Court, provides a different story. She claims that every two weeks a package for Grayson was delivered by two men in uniform. Grayson told Porter the package contained money. One morning in late September, 1920 - she did not remember the precise date - two strangers came and asked for Grayson. After spending most of the day with Grayson, they left together carrying two large suitcases. Grayson told her: "I am having to go away for a little while. I'll be in touch shortly." That was the last she saw of Victor Grayson. (76)

Victor Grayson was never seen alive again. It is believed he was murdered but his body was never found. After Grayson's death Arthur Maundy Gregory continued to sell honours for the next twelve years. In 1932 Gregory attempted to sell a knighthood to Lieutenant Commander Edward Billyard-Leake. He pretended he was interested and then reported the matter of Scotland Yard. Gregory was arrested but he turned it to his advantage as he was now able to blackmail famous people into paying him money in return for not naming them in court. Gregory pleased guilty and therefore did not give evidence of his activities in court. Gregory was sentenced to two months' imprisonment and a fine of £50. On leaving prison Gregory was persuaded to live in Paris where he was paid a pension of £2,000 a year by the Conservative Party. (77)

On 25th August 1939, someone collected Grayson's war medals from the New Zealand Embassy in London. The Ministry of Defence insisted that they would not have handed these medals over unless the man proved he was Grayson. "If Private Grayson was deceased then proof of death would be required". (78)

There is also evidence that Grayson was still alive after the Second World War. Harold P. Smallwood, a former CID officer, first got to know Grayson in 1948. He claimed that after his disappearance, Grayson worked in numerous schools under a false name in Ireland, Kent, Sussex, Switzerland and Austria. Grayson told Smallwood that "he rarely spent more than one term in any school, when he was usually asked to leave because of his drinking habits and his unorthodox method of teaching." Smallwood lost contact with Grayson in 1950. (79)

Primary Sources

(1) W. F. Black, The Labour Leader (1906)

Victor Grayson has a deep rich voice, just made for the open-air and he gave his audience plain, strong, and richly-defined Socialism. Nothing petty or mean, no appeal to unworthy motives, or even the misery of things, but an uplifting, elevating, manly propaganda speech, addressed to the crowd as men. In Victor Grayson, student and orator, the Manchester men have found a prize indeed, and Socialism has gained another valuable asset.

(2) Reg Groves, The Strange Case of Victor Grayson (1975)

The socialists had no money, save the pennies collected amongst their fellow workers in the mills and factories and at meetings. As the campaign grew, money was raised by more desperate measures; watches, household goods, even wedding rings were pawned to keep the supply of money flowing. They had no efficient, smoothworking electoral machinery; it had to be improvised on the spot. The trade union machinery which might well have added much in the way of organisation and wide-flung influence was not likely to give its unstinted support, since the Labour Party refused its endorsement; the ILP, too, was antagonistic, and many of the local union officials favoured a policy of working with the Liberals, not against them.

(3) Victor Grayson, election leaflet (July, 1907)

I am appealing to you as one of your own class. I want emancipation from the wage-slavery of Capitalism. I do not believe that we are divinely destined to be drudges. Through the centuries we have been the serfs of an arrogant aristocracy. We have toiled in the factories and workshops to grind profits with which to glut the greedy maw of the Capitalist class. Their children have been fed upon the fat of the land. Our children have been neglected and handicapped in the struggle for existence. We have served the classes and we have remained a mob. The time for our emancipation has come. We must break the rule of the rich and take our destinies into our own hands. Let charity begin with our children. Workers, who respect their wives, who love their children, and who long for a fuller life for all. A vote for the landowner or the capitalist is treachery to your class. To give your child a better chance than you have had, think carefully ere you make your cross. The other classes have had their day. It is our turn now.

(4) Victor Grayson, speech in Colne Valley (July, 1907)

The placing of women in the same category, constitutionally, as infants, idiots and Peers, does not impress me as either manly or just. While thousands of women are compelled to slave in factories, etc., in order to earn a living; and others are ruined in body and soul by unjust economic laws created and sustained by men, I deem it the meanest tyranny to withhold from women the right to share in making the laws they have to obey. Should I be honoured with your support, I am prepared to give the most immediate and enthusiastic support to a measure giving women the vote on the same terms as men. This is as a step to the larger measure of complete Adult Suffrage

(5) Fred Jowett, The Clarion (November, 1908)

Men are now described as traitors by Victor Grayson who undertook the task of founding a Socialist Movement at a time when the chilling frost of almost universal indifference was far harder to bear than are the violent alternations between the excitement of hostility and the enthusiasm of fellowship in which Victor Grayson now lives and moves.

We must recognise that the man who can make a crowd shout is not necessarily an organizer of men. The gift of platform oratory, skill in making striking phrases, is a dangerous one. It is the man behind that matters. If his skill is employed in setting, not class against class, but men of the same class against their kith and kin, sewing seeds of distrust and hatred where the love of a common cause should produce the fellowship of kindred spirits, it were better if he had no such skill.

(6) Edward Carpenter, My Days and Dreams (1916)

Victor Grayson was a most humorous creature. His fund of anecdotes was inexhaustible, and rarely could a supper party of which he was a member got to bed before three in the morning. On the platform for detailed or constructive argument he was no good, but for criticism of the enemy he was inimitable - the shafts of his wit played like lightening round him, and with his big mouth and flexible upper lip he seemed to be simply browsing off his opponents and eating them up. His disappearance from public life has been quite a loss.

(7) Brian Marriner, What Happened to Victor Grayson? (1984)

As well as blackmail, Arthur Maundy Gregory kept himself in lucrative work by giving the authorities the sort of reports they wanted about communist subversion. The end of the war saw many strikes and Bolshevik plots were held to be behind them all. The Special Branch and M15 competed to provide evidence to support these claims. In the context of the times, this kind of paranoia is easy to understand. The Russian Revolution of 1917 inflamed the British working classes. There were military riots at Folkestone. Thousands of British troops at Calais mutinied, and two divisions had to be recalled from Germany to surround Calais with machine-guns. Leaflets from secret presses were circulated, urging workers to sabotage the war effort. In London even the police were threatening to strike - and those in Liverpool did, in August 1918. When riots and looting broke out in Birkenhead and Liverpool a battleship and two destroyers steamed up the Mersey, playing searchlights on both banks.

By the end of 1918 Gregory had a solid reputation as a "Mr Fixit" with powerful connections. He had already begun his most lucrative business: selling honours for Lloyd George, so that he could gain funds to fight the next election. Lloyd George's Political Fund was to reach some £3,000,000. It is claimed by some that Gregory even suggested the introduction of the new order of the OBE in order to coin more income - even from OBEs he got £20 commission a time. He usually made a point of hinting to prospective buyers that the money was to be used to enable the government to "fight Bolshevism and revolution".

Gregory had an office in Whitehall at 38 Parliament Street, which had a rear entrance in Cannon Row (he was always one to leave himself an escape route). Like all confidence tricksters, he was assiduous in keeping up a good front: he wore silk shirts, expensive suits and shoes, and much personal jewellery. His office was lavishly furnished, with scrambler telephones on the desk and signed photographs of royalty.

He kept a cab-driver on permanent hire, ready to drive him anywhere at a moment's notice, summoned from Cannon Row by an ingenious system of coloured lights in the office window. Gregory liked to flash a gold, inscribed cigarette-case at visitors, which had been presented to him by the Duke of York, later King George VI, for his work for the King George V Fund for Sailors. His staff were required to refer to him at all times as "The Chief", and his hints at powerful connections, many of which were lies, were always backed up by an obsessive attention to detail. For example, he used to excuse himself to visitors by saying he had an important telephone call from "number 10", but this really referred to 10 Hyde Park Terrace, Bayswater Road, which he leased. Frequent visitors to his office were Sir Basil Thomson of the Special Branch and Sir Vernon Kell of M15.

Early in 1918, Gregory was asked by the Special Branch to keep his eyes open for the return to Britain of a "dangerous communist revolutionary", which was an unlikely description of Victor Grayson at the time. Superintendent Quinn of Scotland Yard instructed him: "We believe this man may have friends among the Irish rebels. Whatever it is, Grayson always spells trouble. He can't keep out of it... he will either link up with the Sinn Feiners [Irish nationalists] or the Reds." Gregory promptly made a point of calling on Grayson's wife, posing as a theatrical producer seeking to cast a new play and asking her if she was interested in a part. Until Ruth Grayson died later in the year, Gregory used her to check on Grayson's movements.

Grayson had no sympathy for the Russian revolutionaries, but he did have links with and sympathies for the IRA. On his return he made several secret trips to Ireland, where he had talks with Michael Collins, who was later one of the leaders of the Irish Free State, founded by the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921, until his assassination in 1922. Grayson soon discovered that Gregory was spying on him, and he became determined to expose him - not only as an honours tout but, what was perhaps even more scandalous, as the possible forger of the infamous Casement diaries. To this end, he made the speech in Liverpool threatening to name Gregory and also began to collect signed statements about his activities as an honours tout. Gregory became extremely alarmed. Grayson was a dangerous enemy who was threatening his source of income. As a journalist, Grayson could easily conduct a campaign to discredit Gregory in a number of publications, always providing he took care not to breach the libel laws.

Having been commissioned to keep an eye on Grayson anyway, Gregory now had a double reason to do so. He made it his business to fabricate reports discrediting Grayson, telling his Special Branch and M15 contacts that Grayson was in touch with both Bolshevik agents and the Sinn Fein movement. But if Gregory was observing Grayson closely, he would have realised that the former MP posed no security threat. Politically, he was finished - and his heavy drinking would have made him an unreliable conspirator in any plots to overthrow the government. Gregory would also have known that there was no Russian connection, only an Irish one. But truth was no impediment to Gregory's urgent need to eliminate the man who was a personal threat to him. If Grayson could not be ruined by fabricated reports, then there were other alternatives. One way or another, Victor Grayson had simply got to disappear.

There is some confusion over the last few weeks of Grayson's public life. It is known that he was the victim of a mysterious attack in London in September 1920. He was beaten up in the Strand, and booked into a hotel with stitches in a head wound and a broken arm in a sling. The police confirm the attack: Grayson was taken to Charing Cross Hospital for treatment. Yet the witnesses who saw him walk out of the Georgian Restaurant and vanish did not notice these wounds. He had visited his mother in Liverpool briefly early that same month, but she too saw no wounds. He told her he could not stay long, as he was due to give a speech in Hull. There is no record of any such speech having been made, nor indeed of any hall in Hull having been booked for the purpose, though Grayson may have gone to Hull in order to see someone. It is almost certain that he took the train from Hull straight back to London, where he must have been attacked.

Then comes the climactic scene in the Georgian Restaurant, when Grayson was told his luggage had been delivered in error to the Queen's Hotel, Leicester Square. This has sinister overtones: Gregory, it will be remembered, had his secret headquarters there, at which he used to interview people in connection with his counter-espionage work. There are variations to the last scene, one of which has a well-dressed woman beckoning Grayson out of the restaurant. But the fact remains that Grayson was not seen again after this evening - or rather, not officially.

(8) Theodore Rothstein, The Social Democrat (August, 1909)

At the present time a great confusion exists in the ranks of the Independent Labour Party (I.L.P.). The four most important members of its National Council – Keir Hardie, MacDonald, Snowden and Bruce Glasier (editor of the party organ, the “Labour Leader”) – have, in consequence of the criticism of their policy as leaders of the Party which was expressed at the Easter Conference, demonstratively retired from office. In an open letter addressed to the members of the Party they point out that confusion has existed for some time, caused by the formation within their ranks of a group who do not know what they want, who to-day applaud the Labour Party, and to-morrow demand the formation of a new Socialist Party, who upset the minds of the comrades and undermine their confidence in the leaders by their criticisms and ugly allusions and erroneous statements. How could the business of the Party be carried on under such circumstances? It is indeed not a question of the tactics of the Party – these were laid down once for all when it was founded – but only as to whether the Party is desirous of carrying out these tactics, of insisting upon loyalty to the latter, and of rejecting any actions or methods not in agreement with them. But it is exactly on this point that the Conference has in some instances not supported the Council, thus leaving them, the writers of the letter, no choice but to resign the mandates given by the Party.

Horrible! What can have happened? What is this mysterious group which is confusing the spirits of the Party, and has driven the four most respected leaders and founders of the Party out of the “responsible” posts of the Party Ministry? The proclamation of the four – the quartette, as it is now called in I.L.P. circles – does not mention any names, but all the world knows that the allusion is to the Grayson group. Now, who is Grayson? Who constitute his group? Wherein consists their disruptive activity?

Grayson is still quite a young man, about 27 years old, gifted, full of temperament, a born agitator, but without any sort of theoretical knowledge, no Marxist – more inclined to be an opponent of Marxism – in short, a sentimental Socialist at an age when the wine is not yet fermented. Like all Socialists of this type – and the type is a historical one, dating far back beyond our period – he represents more the tribune of the people than the modern party man, and without being an anarchist or syndicalist, he has a great horror of parliamentarism and of the planned political struggle, which he looks upon as dirty jobbery. This horror seems to be very wide-spread in England, in spite of the prevalent fetish-worship of Parliament, and is caused by the lying and deceitful tactics of the bourgeois parties. It is more to be ascribed to this horror than to firmness of principle, that Grayson, when put up as candidate at a bye-election in the summer of 1907 by the workers of Colne Valley, a Yorkshire constituency, fought for the mandate as a declared Socialist upon an openly Socialist programme, and rejected the compromise proposed by his National Council to appear before the public as a mere “Labour candidate” according to the arrangement of the Labour Party bloc. In spite of his being boycotted by the administration of his own party, as well as that of the Labour Party, and having candidates of both the bourgeois parties opposed to him, he was elected and came into Parliament, the first representative of the workers to get in on a Socialist ticket; thus proving that the hushing-up policy of the National Council of the I.L.P. and their trade unionist colleagues of the bloc of the Labour Party is not a necessity, and occasioning great joy in the S.D.P., as well as among the Socialist elements in the I.L.P., but at least equally great annoyance among the National Council of the latter.

Since that time Grayson has come to be in permanent opposition of the heads of his party, as well as the Labour Party group in general. As he did not join the latter, it boycotted him, and on the few occasions when he spoke in the House (as a Parliamentarian he was chiefly remarkable by his absence) he always came into collision with it. As, for instance, when the English King’s visit to Reval was discussed. The Labour fraction, encouraged by the Radicals, had decided on an interpellation, and as polite people (unlike the Irish who always force their questions upon the “Honourable House”) they entered into negotiations with the Government as to when and under what conditions they would allow this interpellation to be discussed. The Government said they would be glad to meet the wishes of the Labour fraction; only the debate must be closured at a certain hour by the leader of the Labour Party himself, and besides, the speakers must observe a respectful tone towards the King. The group joyfully accepted the conditions, and during some hours made their speeches, which were a curious mixture of attacks upon the Anglo-Russian friendship, and loyal songs of praise to King Edward. The time for adjourning the debate had already passed, but two Liberals spoke in succession, and the leader of the Labour Group, Henderson, showed no signs of interrupting them, Suddenly there arose from his seat, the “enfant terrible,” Grayson, who might well be expected to adopt a sharp tone against the King. Immediately at a sign from the Government, Henderson rose and closured the debate. Grayson protested, but was not allowed to speak.

Grayson came into collision a second time with the Labour Party on the question of unemployment. The Labour Party had neglected this question very much, while it had supported with great enthusiasm the Government’s Licensing Bill. The protests against this outside the House were becoming more frequent and violent, and one fine day when the whole House was deep in discussing a paragraph of the Licensing Bill, Grayson appeared upon the scene and announced to the House an obstruction according to the Irish pattern if it would not occupy itself, instead of with trivialities, with the unemployment question. Grayson’s appearance was unexpected, and one could justly reproach him that he, who never appeared in Parliament and had let pass earlier and much more suitable occasions for a protest, had no right to dictate to his colleagues as to what they should occupy themselves with. Still, this formal reason could only be sufficient to prevent the Labour Party supporting him in his unasked-for and unforeseen protest. But these gentlemen went further, and when the leader of the House, the Prime Minister Asquith, moved Grayson’s suspension, none of them uttered a syllable of protest, some refrained from voting, and the others voted for the proposition.

This, then, is Grayson. No extraordinary hero, as you see; no pioneer; though, on the other hand, not quite an ordinary human being. Whence, then, comes his popularity? How did he manage to create a state of mind in his party by which the most respected leaders have been defeated? The answer is, he has created no state of mind; he has only given expression to that state of mind which was already present; and that is why he has become popular. Perhaps the same state of mind could have been expressed much better and more worthily by a different person. As a matter of fact, the manner in which he gives expression to it is too theatrical, sometimes bordering on caricature. Still, he it was who distinctly voiced the state of mind, and he is made much of by those who agree with him – as a symbol, a standard. Nothing could be more mistaken than to see in him the leader of an opposition. He is no leader, neither can he become one. He is but a point of crystallisation, round which those elements group themselves who have something they wish to express.

What is that state of mind? Who are these elements? The state of mind is: Discontent with the tactics adopted and carried on during the last few years by the I.L.P. leaders towards the Labour Party. Here we reach a much discussed topic, which was also raised in the “Neue Zeit” a short time ago. How should a Socialist Party behave towards a Labour Party like that in England? As Marxists we all indeed know that Socialism can only succeed as a labour movement, that Socialists do not constitute a special organisation opposed to the other labour parties, and that the Socialist idea and the organised proletariat united into a class party must go together, like – to use the striking expression of Comrade Kautsky – the connection between the final goal and the movement. In all Continental countries we have acted upon these principles, but not in England, where their application met with a hindrance in the form of the peculiar historic facts. For while in other countries it was the Socialists themselves who for the first time organised and mobilised the hitherto chaotic, or, to be quite correct, amorphous mass, the proletariat in England had already been organised and actively engaged in the political struggle for decades before the modern Socialists appeared in the historic arena. Therefore Socialism on the Continent was never for a moment separate from the general labour movement, but stood, on the contrary, in its midst as its central force, while in England it arose as something different – even something opposed. What were the English Marxists to do under these circumstances? Should they merge themselves in the Labour Party? But there was no such thing at the beginning of English Marxism, for the few trade unions which engaged in political action did not at that time constitute a special party, but only provided from among their ranks members and candidates for the Liberal Party. All then that the Socialists could do was to seek to win over the masses to themselves; and that they did. Were they successful? No. Marx himself did not succeed when he tried to unite the English labouring masses to the International. As long as the English trade unions were fighting for the suffrage, as a means of securing their right of coalition, it seemed as though Marx’s attempt were destined to succeed. But no sooner was the suffrage – and what a meagre suffrage! – won, and the right of coalition secured, than the unions left the International, and the whole movement was at .an end – the International was dissolved. This precedent cannot be too sharply emphasised in face of the widespread opinion that the S.D.F.’s want of success is to be attributed to its own mistakes. Ah! what Party has not made mistakes? Marx was surely free from great tactical errors, and did he fare any better? Engels, too, discontented with the S.D.F., made, after Marx’s death, several attempts with the Avelings and others, to set on foot a new Socialist movement, and to mobilise the masses for an independent political struggle. How did he fare? Any better than the S.D.F.? No; a thousand times worse. Not only did all the organisations and movements die down after fluttering a little while, but the leaders, the Avelings, Bax, Morris and others, were forced to make their peace with the S.D.F. The difficulty of the S.D.F.’s task lay, not in that body and its methods, but in the historically created state of mind of the English working class, who were unreceptive to Socialist propaganda. Therefore it is out of place to speak of mistakes on the part of the S.D.F. Kautsky, who knows English conditions much better than most critics of the S.D.F., admits this fact, but yet is of the opinion that the S.D.F. did itself a great deal of harm by its irreconcilable criticism of the trade unions. I cannot share this opinion either. In the first place it was not the trade unions that the S.D.F. criticised, but the trade union cretinism, which at that time was so wide-spread, and of which Germany has not been free from samples. The faith in trade union action, and especially trade union diplomacy, as the one means of salvation, was the principal obstacle to the political action of the masses, and how could the S.D.F. not fight against it? In the second place, if these tactics brought the S.D.F. the enmity of the trade unions, thereby injuring the former, how was it with the I.L.P., which was much more gentle in its attitude towards trade union cretinism? Was it any more successful in winning the sympathies of the unions for itself, and for Socialism? It is true that at first Engels had great hopes of this, but the hopes were not realised. The I.L.P. remained for years quite as small a group as the S.D.F., and the unions gave it quite as little attention. Therefore the alleged bitter tone adopted by the S.D.F. towards the trade unions was not a factor in the want of success of this Party’s agitation among the masses.

(9) Victor Grayson, The Lyttleton Times (4th October 1916)

The most important change which the war was making in society, however, was a spirit of change. Wage-earners and capitalists were fighting side-by-side in the ranks, and the capitalist was acquiring the habit of regarding the wage-earners in a very different light from that in which he saw them in the days before the war. War had brought the socially antagonistic classes into closer relations, and the result of the closer knowledge and understanding could not but be beneficial to humanity.

(10) Victor Grayson, The Lyttleton Times (18th November 1916)

Needless to say, the Socialist-Pacifists are anti-conscriptionists, but their real disease is anti-militarism. If a fire broke out in their domestic abodes they would talk to it gently. If a German assaulted their wives or daughter, or if a Prussian crushed the skulls of their babes... they would explain that such conduct was not in keeping with the spirit of the international. I am a Socialist and a democrat to the very roots of my being, but I confess that my bosom comrades are entirely incomprehensible to me. The Labour Party in New Zealand had the chance of their lifetime when the horrid word conscription was mooted. They could and should have accepted the conscription of men, on the guarantee of the Dominion Parliament to conscript capital and wealth... The pacifist (whether he calls himself a Socialist or Quaker) is a greater menace than the guttural Hun in the trenches of Flanders... I hate war and I hate killing. Yet if I account for one of the vassals of the world's mad-dog I shall have done my bit towards world regeneration.